Clomipramine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Anafranil, Clomicalm, others |

| Other names | Clomimipramine; 3-Chloroimipramine; G-34586[1] |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Tricyclic antidepressant (TCA)[2] |

| Main uses | Obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, major depressive disorder, chronic pain[2] |

| Side effects | Dry mouth, constipation, loss of appetite, sleepiness, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, trouble urinating[2] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, intravenous[3] |

| Defined daily dose | 100 mg (by mouth, by injection)[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697002 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | ~50%[5] |

| Protein binding | 96–98%[5] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2D6)[5] |

| Metabolites | Desmethylclomipramine[5] |

| Elimination half-life | CMI: 19–37 hours[5] DCMI: 54–77 hours[5] |

| Excretion | Kidney (51–60%)[5] Feces (24–32%)[5] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H23ClN2 |

| Molar mass | 314.86 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Clomipramine, sold under the brand name Anafranil among others, is a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA).[2] It is used for the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, major depressive disorder, and chronic pain.[2] It may increase the risk of suicide in those over the age of 20.[2] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include dry mouth, constipation, loss of appetite, sleepiness, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and trouble urinating.[2] Serious side effects include an increased risk of suicidal behavior in those under the age of 25, seizures, mania, and liver problems.[2] If stopped suddenly a withdrawal syndrome may occur with headaches, sweating, and dizziness.[2] It is unclear if it is safe for use in pregnancy.[2] Its mechanism of action is not entirely clear but is believed to involve increased levels of serotonin.[2]

Clomipramine was discovered in 1964 by the Swiss drug manufacturer Ciba-Geigy.[6] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[7] It is available as a generic medication.[2] The wholesale price in the developing world is between 0.11 and 0.21 per day as of 2014.[8] In the United States the wholesale costs as of 2018 is about US$9 per day.[9] It was made from imipramine.[6]

Medical uses

Clomipramine has a number of uses in medicine including in the treatment of:

- Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) which is its only U.S. FDA-labeled indication.[10][11] Other regulatory agencies (such as the TGA of Australia and the MHRA of the UK) have also approved clomipramine for this indication.[12][13][14][15]

- Major depressive disorder (MDD) a popular off-label use in the US. It is approved by the Australian TGA and the United Kingdom MHRA for this indication.[12][13][14][15][16] Some have suggested the possible superior efficacy of clomipramine compared to other antidepressants in the treatment of MDD, although at the current time the evidence is insufficient to adequately substantiate this claim.[17]

- Panic disorder with or without agoraphobia.[18][19]

- Body dysmorphic disorder[20]

- Cataplexy associated with narcolepsy. Which is a TGA and MHRA-labeled indication for clomipramine.[14][15]

- Premature ejaculation[21]

- Depersonalization disorder[22]

- Chronic pain with or without organic disease, particularly headache of the tension type.[23]

- Sleep paralysis, with or without narcolepsy

- Enuresis (involuntary urinating in sleep) in children. The effect may not be sustained following treatment, and alarm therapy may be more effective in both the short-term and the long-term.[24] Combining a tricyclic (such as clomipramine) with anticholinergic medication, may be more effective for treating enuresis than the tricyclic alone.[24]

- Trichotillomania[25][26][27]

In a review fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and sertraline to test their relative efficacies in treating OCD, clomipramine was found to be the most effective.[28]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 100 mg (parenteral) or 100 mg (by mouth)[4]

Contraindications

Contraindications include:[13]

- Known hypersensitivity to clomipramine, or any of the excipients or cross-sensitivity to tricyclic antidepressants of the dibenzazepine group

- Recent myocardial infarction

- Any degree of heart block or other cardiac arrhythmias

- Mania

- Severe liver disease

- Narrow angle glaucoma

- Urinary retention

- It must not be given in combination or within 3 weeks before or after treatment with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. (Moclobemide included, however clomipramine can be initiated sooner at 48 hours following discontinuation of moclobemide.)

Pregnancy and lactation

Clomipramine use during pregnancy is associated with congenital heart defects in the newborn.[15][29] It is also associated with reversible withdrawal effects in the newborn.[30] Clomipramine is also distributed in breast milk and hence nursing while taking clomipramine is advised against.[11]

Side effects

Clomipramine has been associated with the following side effects:[10][11][12][13]

Very common (>10% frequency):

- Accommodation (eye)

- Blurred vision

- Nausea

- Dry mouth

- Constipation

- Fatigue

- Weight gain

- Increased appetite

- Dizziness

- Tremor

- Headache

- Myoclonus

- Drowsiness

- Somnolence

- Restlessness

- Micturition disorder

- Sexual dysfunction (erectile dysfunction and loss of libido)

- Hyperhidrosis (profuse sweating)

Common (1–10% frequency):

- Weight loss

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Sinus tachycardia

- Clinically irrelevant ECG changes (e.g. T- and ST-wave changes) in patients of normal cardiac status

- Palpitations

- Tinnitus (hearing ringing in one's ears)

- Mydriasis (dilated pupils)

- Vomiting

- Abdominal disorders

- Diarrhoea

- Decreased appetite

- Transaminases increased

- Alkaline phosphatase increased

- Speech disorders

- Paraesthesia

- Muscle hypertonia

- Dysgeusia

- Memory impairment

- Muscular weakness

- Disturbance in attention

- Confusional state

- Disorientation

- Hallucinations (particularly in elderly patients and patients with Parkinson's disease)

- Anxiety

- Agitation

- Sleep disorders

- Mania

- Hypomania

- Aggression

- Depersonalisation

- Insomnia

- Nightmares

- Aggravation of depression

- Delirium

- Galactorrhoea (lactation that is not associated with pregnancy or breastfeeding)

- Breast enlargement

- Yawning

- Hot flush

- Dermatitis allergic (skin rash, urticaria)

- Photosensitivity reaction

- Pruritus (itching)

Uncommon (0.1–1% frequency):

- Convulsions

- Ataxia

- Arrhythmias

- Elevated blood pressure

- Activation of psychotic symptoms

Very rare (<0.01% frequency):

- Pancytopaenia — an abnormally low amount of all the different types of blood cells in the blood (including platelets, white blood cells and red blood cells).

- Leucopenia — a low white blood cell count.

- Agranulocytosis — basically a worse form of leucopaenia; a dangerously low white blood cell count which leaves one open to life-threatening infections due to the role of the white blood cells in defending the body from invaders.

- Thrombocytopenia — an abnormally low amount of platelets in the blood which are essential to clotting and hence this leads to an increased tendency to bruise and bleed, including, potentially, internally.

- Eosinophilia — an abnormally high number of eosinophils — the cells that fight off parasitic infections — in the blood.

- Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) — a potentially fatal reaction to certain medications that is due to an excessive release of antidiuretic hormone — a hormone that prevents the production of urine by increasing the reabsorption of fluids in the kidney — this results in the development of various electrolyte abnormalities (e.g. hyponatraemia [low blood sodium], hypokalaemia [low blood potassium], hypocalcaemia [low blood calcium]).

- Glaucoma

- Oedema (local or generalised)

- Alopecia (hair loss)

- Hyperpyrexia (a high fever that is above 41.5 °C)

- Hepatitis (liver swelling) with or without jaundice — the yellowing of the eyes, the skin, and mucous membranes due to impaired liver function.

- Abnormal ECG

- Anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions including hypotension

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) — a potentially fatal side effect of antidopaminergic agents such as antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants and antiemetics (drugs that relieve nausea and vomiting). NMS develops over a period of days or weeks and is characterised by the following symptoms:

- Tremor

- Muscle rigidity

- Mental status change (such as confusion, delirium, mania, hypomania, agitation, coma, etc.)

- Hyperthermia (high body temperature)

- Tachycardia (high heart rate)

- Blood pressure changes

- Diaphoresis (sweating profusely)

- Diarrhoea

- Alveolitis allergic (pneumonitis) with or without eosinophilia

- Purpura

- Conduction disorder (e.g. widening of QRS complex, prolonged QT interval, PQ changes, bundle-branch block, torsade de pointes, particularly in patients with hypokalaemia)

Withdrawal

Withdrawal symptoms may occur during gradual or particularly abrupt withdrawal of tricyclic antidepressant drugs. Possible symptoms include: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, insomnia, headache, nervousness, anxiety, dizziness and worsening of psychiatric status.[12] Differentiating between the return of the original psychiatric disorder and clomipramine withdrawal symptoms is important.[31] Clomipramine withdrawal can be severe.[32] Withdrawal symptoms can also occur in neonates when clomipramine is used during pregnancy.[30] A major mechanism of withdrawal from tricyclic antidepressants is believed to be due to a rebound effect of excessive cholinergic activity due to neuroadaptations as a result of chronic inhibition of cholinergic receptors by tricyclic antidepressants. Restarting the antidepressant and slow tapering is the treatment of choice for tricyclic antidepressant withdrawal. Some withdrawal symptoms may respond to anticholinergics, such as atropine or benztropine mesylate.[33]

Overdose

Clomipramine overdose usually presents with the following symptoms:[10][12][13]

- Signs of central nervous system depression such as:

- stupor

- coma

- drowsiness

- restlessness

- ataxia

- Mydriasis

- Convulsions

- Enhanced reflexes

- Muscle rigidity

- Athetoid and choreoathetoid movements

- Serotonin syndrome - a condition with many of the same symptoms as neuroleptic malignant syndrome but has a significantly more rapid onset

- Cardiovascular effects including:

- arrhythmias (including Torsades de pointes)

- tachycardia

- QTc interval prolongation

- conduction disorders

- hypotension

- shock

- heart failure

- cardiac arrest

- Apnoea

- Cyanosis

- Respiratory depression

- Vomiting

- Fever

- Sweating

- Oliguria

- Anuria

There is no specific antidote for overdose and all treatment is purely supportive and symptomatic.[12] Treatment with activated charcoal may be used to limit absorption in cases of oral overdose.[12] Anyone suspected of overdosing on clomipramine should be hospitalised and kept under close surveillance for at least 72 hours.[12] Clomipramine has been reported as being less toxic in overdose than most other TCAs in one meta-analysis but this may well be due to the circumstances surrounding most overdoses as clomipramine is more frequently used to treat conditions for which the rate of suicide is not particularly high such as OCD.[34] In another meta-analysis, however, clomipramine was associated with a significant degree of toxicity in overdose.[35]

Interactions

Clomipramine may interact with a number of different medications, including the monoamine oxidase inhibitors which include isocarboxazid, moclobemide, phenelzine, selegiline and tranylcypromine, antiarrhythmic agents (due to the effects of TCAs like clomipramine on cardiac conduction. There is also a potential pharmacokinetic interaction with quinidine due to the fact that clomipramine is metabolised by CYP2D6 in vivo), diuretics (due to the potential for hypokalaemia (low blood potassium) to develop which increases the risk for QT interval prolongation and torsades de pointes), the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; due to both potential additive serotonergic effects leading to serotonin syndrome and the potential for a pharmacokinetic interaction with the SSRIs that inhibit CYP2D6 [e.g. fluoxetine and paroxetine]) and serotonergic agents such as triptans, other tricyclic antidepressants, tramadol, etc. (due to the potential for serotonin syndrome).[12] Its use is also advised against in those concurrently on CYP2D6 inhibitors due the potential for increased plasma levels of clomipramine and the resulting potential for CNS and cardiotoxicity.[12]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | CMI | DMC | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 0.14–0.28 | 40 | Human/rat | [37][38][39] |

| NET | 38–53.7 | 0.32 | Human/rat | [37][38][39] |

| DAT | ≥2,190 | 2,100 | Human/rat | [37][38][39] |

| 5-HT1A | ≥7,000 | 19,000 | Human/und | [40][38][39] |

| 5-HT1B | >10,000 | ND | Human | [38] |

| 5-HT1D | >10,000 | ND | Human | [38] |

| 5-HT2A | 27–35.5 | 130 | Human/und | [40][38][39] |

| 5-HT2B | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 5-HT2C | 64.6 | ND | Human | [38] |

| 5-HT3 | 460–985 | ND | Rodent | [38][41][42] |

| 5-HT6 | 53.8 | ND | Rat | [43] |

| 5-HT7 | 127 | ND | Rat | [44] |

| α1 | 3.2–38 | 190 | Human/und | [38][45][39] |

| α2 | 525–3,200 | 1,800 | Human/und | [38][45][39] |

| β | 22,000 | 16,000 | Undefined | [39] |

| D1 | 219 | 320 | Human/und | [41][39] |

| D2 | 77.6–190 | 1,200 | Human/und | [38][45][39] |

| D3 | 30–50.1 | ND | Human | [38][41] |

| D4 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| D5 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| H1 | 13–31 | 450 | Human/und | [46][45][39] |

| H2 | 209 | ND | Human | [46] |

| H3 | 9,770 | ND | Human | [46] |

| H4 | 5,750 | ND | Human | [46] |

| mACh | 37 | 92 | Human/und | [45][39] |

| σ1 | 546 | ND | Rat | [47] |

| hERG | 130 (IC50) | ND | Human | [48] |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | ||||

Clomipramine is a reuptake inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine, or a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI); that is, it blocks the reuptake of these neurotransmitters back into neurons by preventing them from interacting with their transporters, thereby increasing their extracellular concentrations in the synaptic cleft and resulting in increased serotonergic and noradrenergic neurotransmission.[49][37] In addition, clomipramine also has antiadrenergic, antihistamine, antiserotonergic, antidopaminergic, and anticholinergic activities. It is specifically an antagonist of the α1-adrenergic receptor, the histamine H1 receptor, the serotonin 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, 5-HT3, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 receptors, the dopamine D1, D2, and D3 receptors, and the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (M1–M5).[45][38] Like other TCAs, clomipramine weakly blocks voltage-dependent sodium channels as well.[49][6][50]

Although clomipramine shows around 100- to 200-fold preference in affinity for the SERT over the NET, its major active metabolite, desmethylclomipramine (norclomipramine), binds to the NET with very high affinity (Ki = 0.32 nM) and with dramatically reduced affinity for the SERT (Ki = 31.6 nM).[51][52] Moreover, desmethylclomipramine circulates at concentrations that are approximately twice those of clomipramine.[53] In accordance, occupancy of both the SERT and the NET has been shown with clomipramine administration in positron emission tomography studies with humans and non-human primates.[54][55] As such, clomipramine is in fact a fairly balanced SNRI rather than only a serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI).[56]

The antidepressant effects of clomipramine are thought to be due to reuptake inhibition of serotonin and norepinephrine,[49] while serotonin reuptake inhibition only is thought to be responsible for the effectiveness of clomipramine in the treatment of OCD. Conversely, antagonism of the H1, α1-adrenergic, and muscarinic acetylcholine receptors is thought to contribute to its side effects.[49] Blockade of the H1 receptor is specifically responsible for the antihistamine effects of clomipramine and side effects like sedation and somnolence (sleepiness).[49] Antagonism of the α1-adrenergic receptor is thought to cause orthostatic hypotension and dizziness.[49] Inhibition of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors is responsible for the anticholinergic side effects of clomipramine like dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, blurred vision, and cognitive/memory impairment.[49] In overdose, sodium channel blockade in the brain is believed to cause the coma and seizures associated with TCAs while blockade of sodium channels in the heart is considered to cause cardiac arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, and death.[49][6] On the other hand, sodium channel blockade is also thought to contribute to the analgesic effects of TCAs, for instance in the treatment of neuropathic pain.[57]

The exceptionally strong serotonin reuptake inhibition of clomipramine likely precludes the possibility of its antagonism of serotonin receptors (which it binds to with more than 100-fold lower affinity than the SERT) resulting in a net decrease in signaling by these receptors. In accordance, while serotonin receptor antagonists like cyproheptadine and chlorpromazine are effective as antidotes against serotonin syndrome,[58][59] clomipramine is nonetheless capable of inducing this syndrome.[56] In fact, while all TCAs are SRIs and serotonin receptor antagonists to varying extents, the only TCAs that are associated with serotonin syndrome are clomipramine and to a lesser extent its dechlorinated analogue imipramine,[56][58] which are the two most potent SRIs of the TCAs (and in relation to this have the highest ratios of serotonin reuptake inhibition to serotonin receptor antagonism).[60] As such, whereas other TCAs can be combined with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (with caution due to the risk of hypertensive crisis from NET inhibition; sometimes done in treatment-resistant depressives), clomipramine cannot be due to the risk of serotonin syndrome and death.[49] Unlike the case of its serotonin receptor antagonism, orthostatic hypotension is a common side effect of clomipramine, suggesting that its blockade of the α1-adrenergic receptor is strong enough to overcome the stimulatory effects on the α1-adrenergic receptor of its NET inhibition.[6][49]

Serotonergic activity

| Medication | SERT | NET | Dosage (mg/day) |

t1/2 (M) (hours) |

Cp (ng/mL) |

Cp / SERT ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amitriptyline | 4.3 | 34.5 | 100–200 | 16 (30) | 100–250 | 23–58 |

| Amoxapine | 58.5 | 16.1 | 200–300 | 8 (30) | 200–500 | 3.4–8.5 |

| Butriptyline[37] | 1,360 | 5,100 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Clomipramine | 0.14–0.28 | 37 | 100–200 | 32 (70) | 150–500 | 536–3,570 |

| Desipramine | 17.5 | 0.8 | 100–200 | 30 | 125–300 | 7.1–17 |

| Dosulepin[61][62][63] | 8.3 | 45.5 | 150–225 | 25 (34) | 50–200 | 6.0–24 |

| Doxepin | 66.7 | 29.4 | 100–200 | 18 (30) | 150–250 | 2.2–3.7 |

| Imipramine | 1.4 | 37 | 100–200 | 12 (30) | 175–300 | 125–214 |

| Iprindole[37] | 1,620 | 1,262 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Lofepramine[37] | 70.0 | 5.4 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Nortriptyline | 18.5 | 4.4 | 75–150 | 31 | 60–150 | 3.2–8.1 |

| Protriptyline | 19.6 | 1.4 | 15–40 | 80 | 100–250 | 5.1–13 |

| Trimipramine[37] | 149 | 2,450 | 75–200 | 16 (30) | 100–300 | 0.67–2.0 |

| Citalopram | 1.4 | 5,100 | 20–40 | 36 | 75–150 | 54–107 |

| Escitalopram | 1.1 | 7,840 | 10–20 | 30 | 40–80 | 36–73 |

| Fluoxetine | 0.8 | 244 | 20–40 | 53 (240) | 100–500 | 125–625 |

| Fluvoxamine | 2.2 | 1,300 | 100–200 | 18 | 100–200 | 45–91 |

| Paroxetine | 0.34 | 40 | 20–40 | 17 | 30–100 | 300–1,000 |

| Sertraline | 0.4 | 417 | 100–150 | 23 (66) | 25–50 | 83–167 |

| Duloxetine | 1.6 | 11.2 | 80–100 | 11 | ? | ? |

| Milnacipran | 123 | 200 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Venlafaxine | 9.1 | 535 | 75–225 | 5 (11) | ? | ? |

| The values for the SERT and NET are Ki (nM). Note that in the Cp / SERT ratio, free versus protein-bound drug concentrations are not accounted for. | ||||||

| Medication | Dosage range (mg/day)[64] |

~80% SERT occupancy (mg/day)[65][66] |

Ratio (dosage / 80% occupancy) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | 20–40 | 40 | 0.5–1 |

| Escitalopram | 10–20 | 10 | 1–2 |

| Fluoxetine | 20–80 | 20 | 1–4 |

| Fluvoxamine | 50–300 | 70 | 0.71–5 |

| Paroxetine | 10–60 | 20 | 0.5–3 |

| Sertraline | 25–200 | 50 | 0.5–4 |

| Duloxetine | 20–60 | 30 | 0.67–2 |

| Venlafaxine | 75–375 | 75 | 1–5 |

| Clomipramine | 50–250 | 10 | 5–25 |

Clomipramine is a very strong SRI.[67][68] Its affinity for the SERT was reported in one study using human tissues to be 0.14 nM, which is considerably higher than that of other TCAs.[38][60] For example, the TCAs with the next highest affinities for the SERT in the study were imipramine, amitriptyline, and dosulepin (dothiepin), with Ki values of 1.4 nM, 4.3 nM, and 8.3 nM, respectively.[60] In addition, clomipramine has a terminal half-life that is around twice as long as that of amitriptyline and imipramine.[60][69] In spite of these differences however, clomipramine is used clinically at the same usual dosages as other serotonergic TCAs (100–200 mg/day).[60] It achieves typical circulating concentrations that are similar in range to those of other TCAs but with an upper limit that is around twice that of amitriptyline and imipramine.[60] For these reasons, clomipramine is the most potent SRI among the TCAs and is far stronger as an SRI than other TCAs at typical clinical dosages.[67][68] In addition, clomipramine is more potent as an SRI than any selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), it is more potent than paroxetine, which is the strongest SSRI.[60]

A positron emission tomography study found that a single low dose of 10 mg clomipramine to healthy volunteers resulted in 81.1% occupancy of the SERT, which was comparable to the 84.9% SERT occupancy by 50 mg fluvoxamine.[54] In the study, single doses of 5 to 50 mg clomipramine resulted in 67.2 to 94.0% SERT occupancy while single doses of 12.5 to 50 mg fluvoxamine resulted in 28.4 to 84.9% SERT occupancy.[54] Chronic treatment with higher doses was able to achieve up to 100.0% SERT occupancy with clomipramine and up to 93.6% SERT occupancy with fluvoxamine.[54] Other studies have found 83% SERT occupancy with 20 mg/day paroxetine and 77% SERT occupancy with 20 mg/day citalopram.[54][70] These results indicate that very low doses of clomipramine are able to substantially occupy the SERT and that clomipramine achieves higher occupancy of the SERT than SSRIs at comparable doses.[54][65] Moreover, clomipramine may be able to achieve more complete occupancy of the SERT at high doses, at least relative to fluvoxamine.[54]

If the ratios of the 80% SERT occupancy dosage and the approved clinical dosage range are calculated and compared for SSRIs, SNRIs, and clomipramine, it can be deduced that clomipramine is by far the strongest SRI used medically.[65][64] The lowest approved dosage of clomipramine can be estimated to be roughly comparable in SERT occupancy to the maximum approved dosages of the strongest SSRIs and SNRIs.[65][64] Because their mechanism of action was originally not known and dose-ranging studies were never conducted, first-generation antipsychotics were dramatically overdosed in patients.[65] It has been suggested that the same may have been true for clomipramine and other TCAs.[65]

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Clomipramine was the first drug that was investigated for and found to be effective in the treatment of OCD.[6][71] In addition, it was the first drug to be approved by the FDA in the United States for the treatment of OCD.[72] The effectiveness of clomipramine in the treatment of OCD is far greater than that of other TCAs, which are comparatively weak SRIs; a meta-analysis found pre- versus post-treatment effect sizes of 1.55 for clomipramine relative to a range of 0.67 for imipramine and 0.11 for desipramine.[73] In contrast to other TCAs, studies have found that clomipramine and SSRIs, which are more potent SRIs, have similar effectiveness in the treatment of OCD.[73] However, multiple meta-analyses have found that clomipramine nonetheless retains a significant effectiveness advantage relative to SSRIs;[74] in the same meta-analysis mentioned previously, the effect sizes of SSRIs in the treatment of OCD ranged from 0.81 for fluoxetine to 1.36 for sertraline (relative to 1.55 for clomipramine).[73] However, the effectiveness advantage for clomipramine has not been apparent in head-to-head comparisons of clomipramine versus SSRIs for OCD.[74] The differences in effectiveness findings could be due to differences in methodologies across non-head-to-head studies.[73][74]

Relatively high doses of SRIs are needed for effectiveness in the treatment of OCD.[75] Studies have found that high dosages of SSRIs above the normally recommended maximums are significantly more effective in OCD treatment than lower dosages (e.g., 250 to 400 mg/day sertraline versus 200 mg/day sertraline).[75][76] In addition, the combination of clomipramine and SSRIs has also been found to be significantly more effective in alleviating OCD symptoms, and clomipramine is commonly used to augment SSRIs for this reason.[75][72] Studies have found that intravenous clomipramine, which is associated with very high circulating concentrations of the drug and a much higher ratio of clomipramine to its metabolite desmethylclomipramine, is more effective than oral clomipramine in the treatment of OCD.[75][6][72] There is a case report of complete remission from OCD for approximately one month following a massive overdose of fluoxetine, an SSRI with a uniquely long duration of action.[77] Taken together, stronger serotonin reuptake inhibition has consistently been associated with greater alleviation of OCD symptoms, and since clomipramine, at the clinical dosages in which it is employed, is effectively the strongest SRI used medically (see table above), this may underlie its unique effectiveness in the treatment of OCD.

In addition to serotonin reuptake inhibition, clomipramine is also a mild but clinically significant antagonist of the dopamine D1, D2, and D3 receptors at high concentrations.[60][74][78] Addition of antipsychotics, which are potent dopamine receptor antagonists, to SSRIs, has been found to significantly augment their effectiveness in the treatment of OCD.[74][79] As such, besides strong serotonin reuptake inhibition, clomipramine at high doses might also block dopamine receptors to treat OCD symptoms, and this could additionally or alternatively be involved in its possible effectiveness advantage over SSRIs.[80][81]

Although clomipramine is probably more effective in the treatment of OCD compared to SSRIs, it is greatly inferior to them in terms of tolerability and safety due to its lack of selectivity for the SERT and promiscuous pharmacological activity.[74][82] In addition, clomipramine has high toxicity in overdose and can potentially result in death, whereas death rarely, if ever, occurs with overdose of SSRIs.[74][82] It is for these reasons that clomipramine, in spite of potentially superior effectiveness to SSRIs, is now rarely used as a first-line agent in the treatment of OCD, with SSRIs being used as first-line therapies instead and clomipramine generally being reserved for more severe cases and as a second-line agent.[82]

Pharmacokinetics

The oral bioavailability of clomipramine is approximately 50%.[10] Peak plasma concentrations occur around 2–6 hours (with an average of 4.7 hours) after taking clomipramine orally and are in the range of 56–154 ng/mL (178–489 nmol/L).[10] Steady-state concentrations of clomipramine are around 134–532 ng/mL (426–1,690 nmol/L), with an average of 218 ng/mL (692 nmol/L), and are reached after 7 to 14 days of repeated dosing.[10] Steady-state concentrations of the active metabolite, desmethylclomipramine, are around 230–550 ng/mL (730–1,750 nmol/L).[10] The volume of distribution (Vd) of clomipramine is approximately 17 L/kg.[11] It binds approximately 97–98% to plasma proteins,[10][11] primarily to albumin.[10] Clomipramine is metabolized in the liver mainly by CYP2D6.[11] It has a terminal half-life of 32 hours, and its N-desmethyl metabolite, desmethylclomipramine, has a terminal half-life of approximately 69 hours.[11] Clomipramine is mostly excreted in urine (60%) and feces (32%).[11]

Chemistry

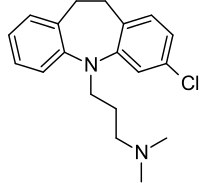

Clomipramine is a tricyclic compound, specifically a dibenzazepine, and possesses three rings fused together with a side chain attached in its chemical structure.[83] Other dibenzazepine TCAs include imipramine, desipramine, and trimipramine.[83] Clomipramine is a derivative of imipramine with a chlorine atom added to one of its rings and is also known as 3-chloroimipramine.[84] It is a tertiary amine TCA, with its side chain-demethylated metabolite desmethylclomipramine being a secondary amine.[85][86] Other tertiary amine TCAs include amitriptyline, imipramine, dosulepin (dothiepin), doxepin, and trimipramine.[87][88] The chemical name of clomipramine is 3-(3-chloro-10,11-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,f]azepin-5-yl)-N,N-dimethylpropan-1-amine and its free base form has a chemical formula of C19H23ClN2 with a molecular weight of 314.857 g/mol.[1] The drug is used commercially almost exclusively as the hydrochloride salt; the free base has been used rarely.[1][89] The CAS Registry Number of the free base is 303-49-1 and of the hydrochloride is 17321-77-6.[1][89]

History

Clomipramine was developed by Geigy as a chlorinated derivative of Imipramine.[6][90] It was first referenced in the literature in 1961 and was patented in 1963.[90] The drug was first approved for medical use in Europe in the treatment of depression in 1970,[90] and was the last of the major TCAs to be marketed.[5] In fact, clomipramine was initially considered to be a "me-too drug" by the FDA, and in relation to this, was declined licensing for depression in the United States.[5] As such, to this day, clomipramine remains the only TCA that is available in the United States that is not approved for the treatment of depression, in spite of the fact that it is a highly effective antidepressant.[91] Clomipramine was eventually approved in the United States for the treatment of OCD in 1989 and became available in 1990.[72][6] It was the first drug to be investigated and found effective in the treatment of OCD.[6][71] The first reports of benefits in OCD were in 1967, and the first double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of clomipramine for OCD was conducted in 1976,[71] with more rigorous clinical studies that solidified its effectiveness conducted in the 1980s.[6] It remained the "gold standard" for the treatment of OCD for many years until the introduction of the SSRIs, which have since largely superseded it due to greatly improved tolerability and safety (although notably not effectiveness).[92][93] Clomipramine is the only TCA that has been shown to be effective in the treatment of OCD and that is approved by the FDA for the treatment of OCD; the other TCAs failed clinical trials for this indication, likely due to insufficient serotonergic activity.[94][95]

Society and culture

Generic names

Clomipramine is the English and French generic name of the drug and its INN, BAN, and DCF, while clomipramine hydrochloride is its USAN, USP, BANM, and JAN.[1][89][96][97] Clomipramina is its generic name in Spanish and Italian and its DCIT, while clomipramin is its generic name in German and clomipraminum is its generic name in Latin.[89][97]

Brand names

Clomipramine is marketed throughout the world mainly under the brand names Anafranil and Clomicalm for use in humans and animals, respectively.[89][97]

Veterinary uses

In the U.S., clomipramine is only licensed to treat separation anxiety in dogs for which it is sold under the brand name Clomicalm.[98] It has proven effective in the treatment of obsessive–compulsive disorders in cats and dogs.[99][100] In dogs, it has also demonstrated similar efficacy to fluoxetine in treating tail chasing.[101] In dogs some evidence suggests its efficacy in treating noise phobia.[102]

Clomipramine has also demonstrated efficacy in treating urine spraying in cats.[103] Various studies have been done on the effects of clomipramine on cats to reduce urine spraying/marking behavior. It has been shown to be able to reduce this behavior by up to 75% in a trial period of four weeks.[104]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 299–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 "Clomipramine Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ Taylor, D; Paton, C; Shitij, K (2012). Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry (11th ed.). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-47-097948-8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 604–605. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 Joseph Zohar (31 May 2012). Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: Current Science and Clinical Practice. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 19–30, 32, 50, 59. ISBN 978-1-118-30801-1. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Clomipramine". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 3 November 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ↑ "NADAC as of 2018-02-07". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 "ANAFRANIL (CLOMIPRAMINE HYDROCHLORIDE) CAPSULE [MALLINCKRODT, INC.]". DailyMed. Mallinckrodt, Inc. October 2012. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 "Anafranil (clomipramine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 12.9 "ANAFRANIL® (clomipramine)" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. NOVARTIS Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Limited. 7 December 2012. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 "Anafranil 75mg SR Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) - (eMC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd. 8 October 2012. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ "Clomipramine 50 mg Capsules, Hard - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (eMC)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ↑ Montgomery, SA; Baldwin, DS; Blier, P; Fineberg, NA; Kasper, S; Lader, M; Lam, RW; Lépine, JP; Möller, HJ; Nutt, DJ; Rouillon, F; Schatzberg, AF; Thase, ME (November 2007). "Which antidepressants have demonstrated superior efficacy? A review of the evidence". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 22 (6): 323–329. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282eff7e0. PMID 17917550. S2CID 16921407.

- ↑ Saeed, SA; Bruce, TJ (May 1998). "Panic Disorder: Effective Treatment Options". American Family Physician. 57 (10): 2405–2412. PMID 9614411. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ↑ Papp, LA; Schneier, FR; Fyer, AJ; Leibowitz, MR; Gorman, JM; Coplan, JD; Campeas, R; Fallon, BA; Klein, DF (October 1997). "Clomipramine treatment of panic disorder: pros and cons". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 (10): 423–425. doi:10.4088/JCP.v58n1002. PMID 9375591.

- ↑ Hollander, E; Allen, A; Kwon, J; Aronowitz, B; Schmeidler, J; Wong, C; Simeon, D (November 1999). "Clomipramine vs desipramine crossover trial in body dysmorphic disorder: selective efficacy of a serotonin reuptake inhibitor in imagined ugliness" (PDF). Archives of General Psychiatry. 56 (11): 1033–1039. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.11.1033. PMID 10565503. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ↑ Palmer, NR; Stuckey, BG (June 2008). "Premature ejaculation: a clinical update" (PDF). The Medical Journal of Australia. 188 (11): 662–666. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01827.x. PMID 18513177. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ↑ Hollander, E.; Hwang; Mullen (1993). "Clinical and research issues in depersonalization syndrome". Psychosomatics. 34 (2): 193–194. doi:10.1016/s0033-3182(93)71919-2. PMID 8456168.

- ↑ Nilsson, HL; Knorring, LV (1989). "Review. Clomipramine in acute and chronic pain syndromes". Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 43 (s20): 101–113. doi:10.3109/08039488909100841.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Caldwell, Patrina H. Y.; Sureshkumar, Premala; Wong, Wicky C. F. (20 January 2016). "Tricyclic and related drugs for nocturnal enuresis in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD002117. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002117.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 26789925.

- ↑ Rothbart, R; Amos, T; Siegfried, N; Ipser, JC; Fineberg, N; Chamberlain, SR; Stein, DJ (November 2013). "Pharmacotherapy for trichotillomania". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (11): CD007662. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007662.pub2. PMID 24214100.

- ↑ "Trichotillomania Medication". Medscape Reference. WebMD. 10 October 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ Franklin, ME; Zagrabbe, K; Benavides, KL (August 2011). "Trichotillomania and its treatment: a review and recommendations". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 11 (8): 1165–1174. doi:10.1586/ern.11.93. PMC 3190970. PMID 21797657.

- ↑ Greist, JH (January 1995). "Efficacy and tolerability of serotonin transport inhibitors in obsessive-compulsive disorder. A meta-analysis". Archives of General Psychiatry. 52 (1): 53–60. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950130053006. PMID 7811162.

- ↑ Källén, B; Otterblad Olausson, P (April 2006). "Antidepressant drugs during pregnancy and infant congenital heart defect". Reproductive Toxicology. 21 (3): 221–222. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.11.006. PMID 16406480.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Bloem, BR.; Lammers, GJ.; Roofthooft, DW.; De Beaufort, AJ.; Brouwer, OF. (July 1999). "Clomipramine withdrawal in newborns". Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 81 (1): F77. doi:10.1136/fn.81.1.f77a. PMC 1720967. PMID 10744432.

- ↑ Zemishlany, Z.; Aizenberg, D.; Hermesh, H.; Weizman, A. (October 1992). "Withdrawal reactions after clomipramine". Harefuah. 123 (7–8): 252–5, 307. PMID 1459499.

- ↑ Kraft, TB. (August 1977). "Severe withdrawal symptoms following use of clomipramine". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 121 (33): 1293. PMID 895917.

- ↑ Wolfe, RM. (August 1997). "Antidepressant withdrawal reactions". Am Fam Physician. 56 (2): 455–62. PMID 9262526.

- ↑ White, N; Litovitz, T; Clancy, C (December 2008). "Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 4 (4): 238–250. doi:10.1007/BF03161207. PMC 3550116. PMID 19031375.

- ↑ Hawton, K.; Bergen, H.; Simkin, S.; Cooper, J.; Waters, K.; Gunnell, D.; Kapur, N. (May 2010). "Toxicity of antidepressants: rates of suicide relative to prescribing and non-fatal overdose". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 196 (5): 354–358. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.070219. PMC 2862059. PMID 20435959.

- ↑ Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 37.5 37.6 37.7 Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (December 1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". European Journal of Pharmacology. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ↑ 38.00 38.01 38.02 38.03 38.04 38.05 38.06 38.07 38.08 38.09 38.10 38.11 38.12 38.13 38.14 Millan MJ, Gobert A, Lejeune F, Newman-Tancredi A, Rivet JM, Auclair A, Peglion JL (2001). "S33005, a novel ligand at both serotonin and norepinephrine transporters: I. Receptor binding, electrophysiological, and neurochemical profile in comparison with venlafaxine, reboxetine, citalopram, and clomipramine". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 298 (2): 565–80. PMID 11454918.

- ↑ 39.00 39.01 39.02 39.03 39.04 39.05 39.06 39.07 39.08 39.09 39.10 39.11 Hyttel J (1994). "Pharmacological characterization of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 9 Suppl 1: 19–26. doi:10.1097/00004850-199403001-00004. PMID 8021435.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Wander TJ, Nelson A, Okazaki H, Richelson E (December 1986). "Antagonism by antidepressants of serotonin S1 and S2 receptors of normal human brain in vitro". European Journal of Pharmacology. 132 (2–3): 115–21. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90596-0. PMID 3816971.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Toll L, Berzetei-Gurske IP, Polgar WE, Brandt SR, Adapa ID, Rodriguez L, Schwartz RW, Haggart D, O'Brien A, White A, Kennedy JM, Craymer K, Farrington L, Auh JS (1998). "Standard binding and functional assays related to medications development division testing for potential cocaine and opiate narcotic treatment medications". NIDA Res. Monogr. 178: 440–66. PMID 9686407.

- ↑ Schmidt AW, Hurt SD, Peroutka SJ (1989). "'[3H]quipazine' degradation products label 5-HT uptake sites". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 171 (1): 141–3. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(89)90439-1. PMID 2533080.

- ↑ Monsma FJ, Shen Y, Ward RP, Hamblin MW, Sibley DR (1993). "Cloning and expression of a novel serotonin receptor with high affinity for tricyclic psychotropic drugs". Mol. Pharmacol. 43 (3): 320–7. PMID 7680751.

- ↑ Ruat M, Traiffort E, Leurs R, Tardivel-Lacombe J, Diaz J, Arrang JM, Schwartz JC (1993). "Molecular cloning, characterization, and localization of a high-affinity serotonin receptor (5-HT7) activating cAMP formation". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90 (18): 8547–51. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.8547R. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.18.8547. PMC 47394. PMID 8397408.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 Richelson E, Nelson A (July 1984). "Antagonism by antidepressants of neurotransmitter receptors of normal human brain in vitro". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 230 (1): 94–102. PMID 6086881. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 Appl H, Holzammer T, Dove S, Haen E, Strasser A, Seifert R (2012). "Interactions of recombinant human histamine H₁R, H₂R, H₃R, and H₄R receptors with 34 antidepressants and antipsychotics". Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 385 (2): 145–70. doi:10.1007/s00210-011-0704-0. PMID 22033803.

- ↑ Shirayama Y, Nishikawa T, Umino A, Takahashi K (1993). "p-chlorophenylalanine-reversible reduction of sigma binding sites by chronic imipramine treatment in rat brain". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 237 (1): 117–26. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(93)90100-v. PMID 8359206.

- ↑ Jo SH, Hong HK, Chong SH, Won KH, Jung SJ, Choe H (2008). "Clomipramine block of the hERG K+ channel: accessibility to F656 and Y652". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 592 (1–3): 19–25. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.06.094. PMID 18634780.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 49.5 49.6 49.7 49.8 49.9 Stephen M. Stahl (28 October 2013). Mood Disorders and Antidepressants: Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–104, 106–108. ISBN 978-1-107-72992-6.

- ↑ Kerry Ressler; Daniel Pine; Barbara Rothbaum (15 April 2015). Anxiety Disorders. Oxford University Press. pp. 254–. ISBN 978-0-19-939514-9. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ↑ Ross J. Baldessarini (2 October 2012). Chemotherapy in Psychiatry: Pharmacologic Basis of Treatments for Major Mental Illness. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 173–. ISBN 978-1-4614-3710-9. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ↑ Progress in Drug Research. Birkhäuser. 6 December 2012. pp. 80–. ISBN 978-3-0348-8391-7. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ↑ Dawson Hedges; Colin Burchfield (2006). Mind, Brain, and Drug: An Introduction to Psychopharmacology. Pearson/Allyn and Bacon. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-205-35556-3.

[...] desmethylclomipramine levels may be twice as high as those of clomipramine (Rudorfer & Potter, 1999).

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 54.4 54.5 54.6 Suhara T, Takano A, Sudo Y, Ichimiya T, Inoue M, Yasuno F, Ikoma Y, Okubo Y (2003). "High levels of serotonin transporter occupancy with low-dose clomipramine in comparative occupancy study with fluvoxamine using positron emission tomography". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 60 (4): 386–91. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.386. PMID 12695316.

- ↑ Takano A, Nag S, Gulyás B, Halldin C, Farde L (2011). "NET occupancy by clomipramine and its active metabolite, desmethylclomipramine, in non-human primates in vivo". Psychopharmacology. 216 (2): 279–86. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2212-9. PMID 21336575.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 P K Gillman (July 2007). "Tricyclic antidepressant pharmacology and therapeutic drug interactions updated". Br J Pharmacol. 151 (6): 737–748. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0707253. PMC 2014120. PMID 17471183.

- ↑ Peter Wilson; Paul Watson; Jennifer Haythornwaite; Troels Jensen (26 September 2008). Clinical Pain Management Second Edition: Chronic Pain. CRC Press. pp. 345–. ISBN 978-0-340-94008-2. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Wang RZ, Vashistha V, Kaur S, Houchens NW (2016). "Serotonin syndrome: Preventing, recognizing, and treating it". Cleve Clin J Med. 83 (11): 810–817. doi:10.3949/ccjm.83a.15129. PMID 27824534.

- ↑ Alusik S, Kalatova D, Paluch Z (2014). "Serotonin syndrome". Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 35 (4): 265–73. PMID 25038602.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 60.5 60.6 60.7 60.8 Laurence Brunton; Bruce A. Chabner; Bjorn Knollman (14 January 2011). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, Twelfth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 400,406,409. ISBN 978-0-07-176939-6. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ Christopher M. Doran (20 March 2013). Prescribing Mental Health Medication: The Practitioner's Guide. Routledge. pp. 506–. ISBN 978-1-136-28009-2.

- ↑ Richard C. Dart (2004). Medical Toxicology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 835–. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ↑ Adriana P. Tiziani (24 May 2017). Havard's Nursing Guide to Drugs - Mobile optimised site. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1464–. ISBN 978-0-7295-8605-4.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Gerald P. Koocher; John C. Norcross; Beverly A. Greene Ph.D. (4 September 2013). Psychologists' Desk Reference. Oxford University Press. pp. 442–. ISBN 978-0-19-984550-7.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 65.4 65.5 Gründer G, Hiemke C, Paulzen M, Veselinovic T, Vernaleken I (2011). "Therapeutic plasma concentrations of antidepressants and antipsychotics: lessons from PET imaging". Pharmacopsychiatry. 44 (6): 236–48. doi:10.1055/s-0031-1286282. PMID 21959785.

- ↑ Kasper S, Sacher J, Klein N, Mossaheb N, Attarbaschi-Steiner T, Lanzenberger R, Spindelegger C, Asenbaum S, Holik A, Dudczak R (2009). "Differences in the dynamics of serotonin reuptake transporter occupancy may explain superior clinical efficacy of escitalopram versus citalopram". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 24 (3): 119–25. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e32832a8ec8. PMID 19367152. S2CID 17470375.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Serena-Lynn Brown; Herman Meïr Praag (1991). The Role of Serotonin in Psychiatric Disorders. Psychology Press. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-0-87630-589-8.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Dan J. Stein; Michael H. Stone (1 February 1997). Essential Papers on Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. NYU Press. pp. 453–. ISBN 978-0-8147-8661-1.

- ↑ Jie Jack Li (2015). Top Drugs: History, Pharmacology, Syntheses. Oxford University Press. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-0-19-936258-5.

- ↑ Meyer JH, Wilson AA, Ginovart N, Goulding V, Hussey D, Hood K, Houle S (2001). "Occupancy of serotonin transporters by paroxetine and citalopram during treatment of depression: a [(11)C]DASB PET imaging study". Am J Psychiatry. 158 (11): 1843–9. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1843. PMID 11691690.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 Jose A. Yaryura-Tobias; Fugen A. Neziroglu (1997). Obsessive-compulsive Disorder Spectrum: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-0-88048-707-8.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 Robert Hudak; Darin D. Dougherty (17 February 2011). Clinical Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders in Adults and Children. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-139-49626-1.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 73.3 Eddy KT, Dutra L, Bradley R, Westen D (2004). "A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder". Clin Psychol Rev. 24 (8): 1011–30. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.004. PMID 15533282.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 74.5 74.6 Hollander E, Kaplan A, Allen A, Cartwright C (2000). "Pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 23 (3): 643–56. doi:10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70186-6. PMID 10986733.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 Kellner M (2010). "Drug treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 12 (2): 187–97. PMC 3181958. PMID 20623923.

- ↑ Byerly MJ, Goodman WK, Christensen R (1996). "High doses of sertraline for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder". Am J Psychiatry. 153 (9): 1232–3. doi:10.1176/ajp.153.9.1232b. PMID 8780435.

- ↑ Leonard HL, Topol D, Bukstein O, Hindmarsh D, Allen AJ, Swedo SE (1994). "Clonazepam as an augmenting agent in the treatment of childhood-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder". J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 33 (6): 792–4. doi:10.1097/00004583-199407000-00003. PMID 8083135.

- ↑ Austin LS, Lydiard RB, Ballenger JC, Cohen BM, Laraia MT, Zealberg JJ, Fossey MD, Ellinwood EH (1991). "Dopamine blocking activity of clomipramine in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder". Biol. Psychiatry. 30 (3): 225–32. doi:10.1016/0006-3223(91)90107-w. PMID 1832972.

- ↑ Dold M, Aigner M, Lanzenberger R, Kasper S (2013). "Antipsychotic augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials". Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 16 (3): 557–74. doi:10.1017/S1461145712000740. PMID 22932229.

- ↑ Fontenelle LF, Nascimento AL, Mendlowicz MV, Shavitt RG, Versiani M (2007). "An update on the pharmacological treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 8 (5): 563–83. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.5.563. PMID 17376013.

- ↑ Hood, Sean; Alderton, Deirdre; Castle, David (2016). "Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: Treatment and Treatment Resistance". Australasian Psychiatry. 9 (2): 118–127. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1665.2001.00316.x. ISSN 1039-8562.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 Jonathan S. Abramowitz; Dean McKay; Eric A. Storch (12 June 2017). The Wiley Handbook of Obsessive Compulsive Disorders. Wiley. pp. 1076–. ISBN 978-1-118-89025-7.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Michael S Ritsner (15 February 2013). Polypharmacy in Psychiatry Practice, Volume I: Multiple Medication Use Strategies. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-94-007-5805-6. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ↑ Psychopharmacology Bulletin. National Institute of Mental Health. 1984.

Clomipramine or 3-chloro-imipramine (Figure 4) is imipramine with a chlorine atom added to one of its rings.

- ↑ Neal R. Cutler; John J. Sramek; Prem K. Narang (20 September 1994). Pharmacodynamics and Drug Development: Perspectives in Clinical Pharmacology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-471-95052-3. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ↑ Pavel Anzenbacher; Ulrich M. Zanger (23 February 2012). Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 302–. ISBN 978-3-527-64632-6. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ↑ Patricia K. Anthony (2002). Pharmacology Secrets. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-1-56053-470-9. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ↑ Philip Cowen; Paul Harrison; Tom Burns (9 August 2012). Shorter Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. OUP Oxford. pp. 532–. ISBN 978-0-19-162675-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 89.3 89.4 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 259–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 Andersen J, Kristensen AS, Bang-Andersen B, Strømgaard K (2009). "Recent advances in the understanding of the interaction of antidepressant drugs with serotonin and norepinephrine transporters". Chem. Commun. (25): 3677–92. doi:10.1039/b903035m. PMID 19557250.

- ↑ Bette Bonder (2010). Psychopathology and Function. SLACK. pp. 239–. ISBN 978-1-55642-922-4.

- ↑ Richard W. Swanson (1996). Family Practice Review: A Problem Oriented Approach. Mosby. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-8151-8624-3.

Until very recently, the "gold standard" of pharmacologic therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder has been clomipramine. At this time, however, the SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) have become the drugs of choice.

- ↑ Thomas E. Schlaepfer; Charles B. Nemeroff (2012). Neurobiology of Psychiatric Disorders. Elsevier. pp. 677–. ISBN 978-0-444-52002-9.

- ↑ Martin M. Antony; Murray B. Stein (2009). Oxford Handbook of Anxiety and Related Disorders. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 376–. ISBN 978-0-19-530703-0.

- ↑ Lata K. McGinn; William C. Sanderson (1 June 1999). Treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Jason Aronson, Incorporated. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-1-4616-3230-6.

- ↑ I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 "Clomipramine". Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ "CLOMICALM clomipramine tablet CLOMIPRAMINE- clomipramine powder Novartis Animal Health US, Inc". Drugs@FDA. Novartis Animal Health US, Inc. December 1998. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ Seksel, K; Lindeman, MJ (May 1998). "Use of clomipramine in the treatment of anxiety-related and obsessive-compulsive disorders in cats". Australian Veterinary Journal. 76 (5): 317–321. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1998.tb12353.x. PMID 9631696.

- ↑ Overall, KL; Dunham, AE (November 2002). "Clinical features and outcome in dogs and cats with obsessive-compulsive disorder: 126 cases (1989-2000)" (PDF). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 221 (10): 1445–1452. doi:10.2460/javma.2002.221.1445. PMID 12458615. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ Yalcin, E (2010). "Comparison of clomipramine and fluoxetine treatment of dogs with tail chasing". Tierarztl Prax Ausg K Kleintiere Heimtiere. 38 (5): 295–299. doi:10.1055/s-0038-1622860. PMID 22215314. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ Seksel, K; Lindeman, MJ (April 2001). "Use of clomipramine in treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, separation anxiety and noise phobia in dogs: a preliminary, clinical study". Australian Veterinary Journal. 79 (4): 252–256. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2001.tb11976.x. PMID 11349411.

- ↑ King, JN; Steffan, J; Heath, SE; Simpson, BS; Crowell-Davis, SL; Harrington, LJ; Weiss, AB; Seewald, W (September 2004). "Determination of the dosage of clomipramine for the treatment of urine spraying in cats". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 225 (6): 881–887. doi:10.2460/javma.2004.225.881. PMID 15485047.

- ↑ Landsberg, G.M.; Wilson, A.L. (2005). "Effects of clomipramine on cats presented for urine marking". J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 41 (1): 3–11. doi:10.5326/0410003. PMID 15634861.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1: long volume value

- Use dmy dates from December 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Alpha-1 blockers

- Antihistamines

- Chloroarenes

- Novartis brands

- Dibenzazepines

- Dimethylamino compounds

- Dopamine antagonists

- Muscarinic antagonists

- Obsessive–compulsive disorder

- Serotonin antagonists

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

- Tricyclic antidepressants

- World Health Organization essential medicines

- RTT