Prazosin

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Minipress, Vasoflex, Lentopres, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | α1-blocker[1] |

| Main uses | High blood pressure, enlarged prostate, PTSD[1] |

| Side effects | Dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, heart palpitations[1] |

| Addiction risk | None |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Onset of action | 30–90 minutes[3] |

| Duration of action | 10–24 hours[4] |

| Defined daily dose | 5 mg[5] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682245 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | ~60% |

| Protein binding | 97%[4] |

| Elimination half-life | 2–3 hours[4] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

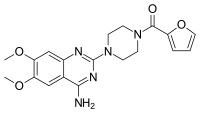

| Formula | C19H21N5O4 |

| Molar mass | 383.408 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Prazosin is a medication primarily used to treat high blood pressure, symptoms of an enlarged prostate, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[1] It is a less preferred treatment of high blood pressure.[1] Other uses may include heart failure and Raynaud syndrome.[6] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, and heart palpitations.[1] Serious side effects may include low blood pressure with standing and depression.[1][6] Prazosin is an α1-blocker.[1] It works to decrease blood pressure by dilating blood vessels and helps with an enlarged prostate by relaxing the outflow of the bladder.[1] How it works in PTSD is not entirely clear.[1]

Prazosin was patented in 1965 and came into medical use in 1974.[7] It is available as a generic medication.[1] A month supply in the United Kingdom costs about £3.50 as of 2019.[6] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$20.[8] In 2017, it was the 227th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[9][10]

Medical use

Prazosin is active after oral administration and has a minimal effect on cardiac function due to its alpha-1 adrenergic receptor selectivity. When prazosin is started, however, heart rate and contractility can increase in order to maintain the pre-treatment blood pressures because the body has reached homeostasis at its abnormally high blood pressure. The blood pressure lowering effect becomes apparent when prazosin is taken for longer periods of time. The heart rate and contractility go back down over time and blood pressure decreases.

The antihypertensive characteristics of prazosin make it a second-line choice for the treatment of high blood pressure.[11]

Prazosin is also useful in treating urinary hesitancy associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia, blocking alpha-1 adrenergic receptors, which control constriction of both the prostate and urethra. Although not a first-line choice for either hypertension or benign prostatic hyperplasia, it is a choice for people who present with both problems concomitantly.[11]

There is some evidence that this medication is effective in treating nightmares, based on mixed results in randomized controlled trials. Prazosin was, however, shown to be more effective when treating nightmares related to PTSD.[12]

The medication maybe recommended for severe stings from the Indian red scorpion.[13][14]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 5 mg by mouth.[5]

Side effects

Common (4–10% frequency) side effects of prazosin include dizziness, headache, drowsiness, lack of energy, weakness, palpitations, and nausea.[15] Less frequent (1–4%) side effects include vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, edema, orthostatic hypotension, dyspnea, syncope, vertigo, depression, nervousness, and rash.[15] A very rare side effect of prazosin is priapism.[15][16] One phenomenon associated with prazosin is known as the "first dose response", in which the side effects of the drug – specifically orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, and drowsiness – are especially pronounced in the first dose.[15]

Orthostatic hypotension and syncope are associated with the body's poor ability to control blood pressure without active alpha-adrenergic receptors. People on prazosin should be told to rise to stand up slowly, since their poor baroreflex may cause them to faint if their blood pressure is not adequately maintained during standing. The nasal congestion is due to dilation of vessels in the nasal mucosa.[medical citation needed]

Mechanism of action

Prazosin is an α1-blocker that acts as an inverse agonist at alpha-1 adrenergic receptors, including α1A-, α1B-, and α1D-receptor subtypes.[17] These receptors are found on vascular smooth muscle, where they are responsible for the vasoconstrictive action of norepinephrine.[18] They are also found throughout the central nervous system.[19] Alpha-1 adrenergic receptors have been found on immune cells, where catecholamine binding can stimulate and enhance cytokine production.[20][21]

Society and culture

Cost

A month supply in the United Kingdom costs about £3.50 as of 2019.[6] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$20.[8] In 2017, it was the 227th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[9][10]

-

Prazosin costs (US)

-

Prazosin prescriptions (US)

Research

Prazosin has been shown to prevent death in animal models of cytokine storm.[22] As a repurposed drug, prazosin is being investigated for the prevention of cytokine storm syndrome and complications of COVID-19 where it is thought to decrease cytokine dysregulation.[23][21][24]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 "Prazosin Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Prazosin (Minipress) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 26 November 2019. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ↑ Packer M, Meller J, Gorlin R, Herman MV (March 1979). "Hemodynamic and clinical tachyphylaxis to prazosin-mediated afterload reduction in severe chronic congestive heart failure". Circulation. 59 (3): 531–9. doi:10.1161/01.cir.59.3.531. PMID 761333.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Prazosin". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 766. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 455. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Prazosin Hydrochloride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Shen, Howard (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-59541-101-3.

- ↑ Kung S, Espinel Z, Lapid MI (September 2012). "Treatment of nightmares with prazosin: a systematic review". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 87 (9): 890–900. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.05.015. PMC 3538493. PMID 22883741.

- ↑ Bawaskar HS, Bawaskar PH (2008). "Scorpion sting: A study of clinical manifestations and treatment regimes" (PDF). Current Science. 95 (9): 1337–1341. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ↑ Bawaskar HS, Bawaskar PH (January 2007). "Utility of scorpion antivenin vs prazosin in the management of severe Mesobuthus tamulus (Indian red scorpion) envenoming at rural setting" (PDF). The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 55: 14–21. PMID 17444339. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 "Minipress Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Pfizer. February 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ Bhalla AK, Hoffbrand BI, Phatak PS, Reuben SR (October 1979). "Prazosin and priapism". British Medical Journal. 2 (6197): 1039. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.6197.1039. PMC 1596841. PMID 519276.

- ↑ "Prazosin: Biological activity". IUPHAR. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ "Prazosin: Clinical data". IUPHAR. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Archived from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

This sympatholytic drug is used in the treatment of hypertension, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. ... Antagonist of alpha-1 adrenoceptors on vascular smooth muscle, thereby inhibiting the vasoconstrictor effect of circulating and locally-released adrenaline and noradrenaline, resulting in peripheral vasodilation.

- ↑ Day HE, Campeau S, Watson SJ, Akil H (July 1997). "Distribution of alpha 1a-, alpha 1b- and alpha 1d-adrenergic receptor mRNA in the rat brain and spinal cord". Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 13 (2): 115–39. doi:10.1016/S0891-0618(97)00042-2. PMID 9285356.

- ↑ Heijnen, Cobi J.; van der Voort, Charlotte Rouppe; Wulffraat, Nico; van der Net, Janjaap; Kuis, Wietse; Kavelaars, Annemieke (December 1996). "Functional α1-adrenergic receptors on leukocytes of patients with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 71 (1–2): 223–226. doi:10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00125-7. ISSN 0165-5728. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Konig, Maximilian F.; Powell, Michael A.; Staedtke, Verena; Bai, Ren-Yuan; Thomas, David L.; Fischer, Nicole M.; Huq, Sakibul; Khalafallah, Adham M.; Koenecke, Allison; Xiong, Ruoxuan; Mensh, Brett (30 April 2020). "Preventing cytokine storm syndrome in COVID-19 using α-1 adrenergic receptor antagonists". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. doi:10.1172/JCI139642. ISSN 0021-9738. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ↑ Staedtke, Verena; Bai, Ren-Yuan; Kim, Kibem; Darvas, Martin; Davila, Marco L.; Riggins, Gregory J.; Rothman, Paul B.; Papadopoulos, Nickolas; Kinzler, Kenneth W.; Vogelstein, Bert; Zhou, Shibin (December 2018). "Disruption of a self-amplifying catecholamine loop reduces cytokine release syndrome". Nature. 564 (7735): 273–277. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0774-y. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 6512810. PMID 30542164. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ↑ "Preventing 'Cytokine Storm' May Ease Severe COVID-19 Symptoms". HHMI.org. Archived from the original on 27 May 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ↑ "Prazosin to Prevent COVID-19 (PREVENT-COVID Trial) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Use dmy dates from January 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2020

- Alpha-1 blockers

- Antihypertensive agents

- Anxiolytics

- Pfizer brands

- Carboxamides

- Catechol ethers

- Furans

- Guanidines

- Piperazines

- Quinazolines

- RTT

- Vasodilators