Clonazepam

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | kləʊˈnazɪpam |

| Trade names | Klonopin, Rivotril, others[1] |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Benzodiazepine |

| Main uses | Seizures, panic disorder, movement disorder (akathisia)[2] |

| Side effects | Sleepiness, poor coordination, agitation[2] |

| Dependence risk | Physical: Low to moderate[4] Psychological: Moderate to high[4] |

| Addiction risk | Moderate[5] |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | By mouth, intramuscular, intravenous, sublingual |

| Onset of action | Within an hour[6] |

| Duration of action | 6–12 hours[6] |

| Defined daily dose | 8 mg[7] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682279 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 90% |

| Protein binding | ≈85% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A)[2] |

| Metabolites | 7-aminoclonazepam; 7-acetaminoclonazepam; 3-hydroxy clonazepam[8][9] |

| Elimination half-life | 18–60 hours[10] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

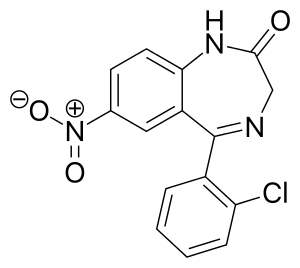

| Formula | C15H10ClN3O3 |

| Molar mass | 315.715 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Clonazepam, sold under the brand Klonopin among others, is a medication used to prevent and treat seizures, panic disorder, and the movement disorder known as akathisia.[2] It is a tranquilizer of the benzodiazepine class.[2] It is taken by mouth.[2] Effects begin within one hour and last between six and twelve hours.[6]

Common side effects include sleepiness, poor coordination, and agitation.[2] Long-term use may result in tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms if stopped abruptly.[2] Dependence occurs in one-third of people who take clonazepam for longer than four weeks.[10] There is an increased risk of suicide, particularly in people who are already depressed.[2][11] If used during pregnancy it may result in harm to the baby.[2] Clonazepam binds to GABAA receptors, thus increasing the effect of the chief inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[10]

Clonazepam was patented in 1960 and went on sale in 1975 in the United States from Roche.[12][13] It is available as a generic medication.[2] The wholesale cost in the developing world is between US$0.01 and US$0.07 per pill.[14] In the United States, the pills are about US$0.40 each.[2] In 2017, it was the 34th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 20 million prescriptions.[15][16] In many areas of the world it is commonly used as a recreational drug.[17][18]

Medical uses

Clonazepam is used for short term management of epilepsy and panic disorder with or without agoraphobia.[19][20][21]

Seizures

Clonazepam, like other benzodiazepines, while being a first-line treatment for acute seizures, is not suitable for the long-term treatment of seizures due to the development of tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects.

Clonazepam has been found effective in treating epilepsy in children, and the inhibition of seizure activity seemed to be achieved at low plasma levels of clonazepam.[22] As a result, clonazepam is sometimes used for certain rare childhood epilepsies; however, it has been found to be ineffective in the control of infantile spasms.[23] Clonazepam is mainly prescribed for the acute management of epilepsies. Clonazepam has been found to be effective in the acute control of non-convulsive status epilepticus; however, the benefits tended to be transient in many people, and the addition of phenytoin for lasting control was required in these patients.[24]

It is also approved for treatment of typical and atypical absences (seizures), infantile myoclonic, myoclonic, and akinetic seizures.[25] A subgroup of people with treatment resistant epilepsy may benefit from long-term use of clonazepam; the benzodiazepine clorazepate may be an alternative due to its slow onset of tolerance.[10]

Anxiety disorders

- Panic disorder with or without agoraphobia.[26]

- Clonazepam has also been found effective in treating other anxiety disorders, such as social phobia, but this is an off-label use.[27][28]

The effectiveness of clonazepam in the short-term treatment of panic disorder has been demonstrated in controlled clinical trials. Some long-term trials have suggested a benefit of clonazepam for up to three years without the development of tolerance but these trials were not placebo-controlled.[citation needed] Clonazepam is also effective in the management of acute mania.[29]

Muscle disorders

Restless legs syndrome can be treated using clonazepam as a third-line treatment option as the use of clonazepam is still investigational.[30][31] Bruxism also responds to clonazepam in the short-term.[32] Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder responds well to low doses of clonazepam.[33]

- The treatment of acute and chronic akathisia induced by neuroleptics, also called antipsychotics.[34][35]

- Spasticity related to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.[36]

- Alcohol withdrawal syndrome[37]

Other

- Benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam, are sometimes used for the treatment of mania or acute psychosis-induced aggression. In this context, benzodiazepines are given either alone, or in combination with other first-line drugs such as lithium, haloperidol or risperidone.[38][39] The effectiveness of taking benzodiazepines along with antipsychotic medication is unknown, and more research is needed to determine if benzodiazepines are more effective than antipsychotics when urgent sedation is required.[39]

- Hyperekplexia[40]

- Many forms of parasomnia and other sleep disorders are treated with clonazepam.[41]

- It is not effective for preventing migraines.[42]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 8 mg by mouth or by injection.[7]

Contraindications

Coma; current alcohol abuse; current drug abuse; and respiratory depression.[43]

Side effects

Common

Less common

- Confusion[10]

- Irritability and aggression[45]

- Psychomotor agitation[46]

- Lack of motivation[47]

- Loss of libido

- Impaired motor function[vague]

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired balance

- Dizziness

- Cognitive impairments[vague][48]

- Hallucinations.[49]

- Short-term memory loss[50]

- Anterograde amnesia (common with higher doses)[51]

- Some users report hangover-like symptoms of drowsiness, headaches, sluggishness, and irritability upon waking up if the medication was taken before sleep. This is likely the result of the medication's long half-life, which continues to affect the user after waking up.[52][53][54] While benzodiazepines induce sleep, they tend to reduce the quality of sleep by suppressing or disrupting REM sleep.[55] After regular use, rebound insomnia may occur when discontinuing clonazepam.[56]

- Benzodiazepines may cause or worsen depression.[10]

Occasional

- Dysphoria[57]

- Induction of seizures[58][59] or increased frequency of seizures[60]

- Personality changes[61]

- Behavioural disturbances[62]

- Ataxia[10]

Rare

- Suicide through disinhibition[11]

- Psychosis[63]

- Incontinence[64][65][66]

- Liver damage[67]

- Paradoxical behavioural disinhibition[10][68] (most frequently in children, the elderly, and in persons with developmental disabilities)

- Rage

- Excitement

- Impulsivity

The long-term effects of clonazepam can include depression,[10] disinhibition, and sexual dysfunction.[69]

Drowsiness

Clonazepam, like other benzodiazepines, may impair a person's ability to drive or operate machinery. The central nervous system depressing effects of the drug can be intensified by alcohol consumption, and therefore alcohol should be avoided while taking this medication. Benzodiazepines have been shown to cause dependence. Patients dependent on clonazepam should be slowly titrated off under the supervision of a qualified healthcare professional to reduce the intensity of withdrawal or rebound symptoms.

- Anxiety

- Irritability

- Insomnia

- Tremors

- Headaches

- Stomach pain

- Nausea

- Hallucinations

- Suicidal thoughts or urges

- Depression

- Fatigue

- Dizziness

- Sweating

- Confusion

- Potential to exacerbate existing panic disorder upon discontinuation

- Seizures[70] similar to delirium tremens (with long-term use of excessive doses)

Benzodiazepines such as clonazepam can be very effective in controlling status epilepticus, but, when used for longer periods of time, some potentially serious side-effects may develop, such as interference with cognitive functions and behavior.[71] Many individuals treated on a long-term basis develop a dependence. Physiological dependence was demonstrated by flumazenil-precipitated withdrawal.[72] Use of alcohol or other CNS depressants while taking clonazepam greatly intensifies the effects (and side effects) of the drug.

A recurrence of symptoms of the underlying disease should be separated from withdrawal symptoms.[73]

Tolerance and withdrawal

Like all benzodiazepines, clonazepam is a GABA-positive allosteric modulator.[74][75] One-third of individuals treated with benzodiazepines for longer than four weeks develop a dependence on the drug and experience a withdrawal syndrome upon dose reduction. High dosage and long-term use increase the risk and severity of dependence and withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal seizures and psychosis can occur in severe cases of withdrawal, and anxiety and insomnia can occur in less severe cases of withdrawal. A gradual reduction in dosage reduces the severity of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Due to the risks of tolerance and withdrawal seizures, clonazepam is generally not recommended for the long-term management of epilepsies. Increasing the dose can overcome the effects of tolerance, but tolerance to the higher dose may occur and adverse effects may intensify. The mechanism of tolerance includes receptor desensitization, down regulation, receptor decoupling, and alterations in subunit composition and in gene transcription coding.[10]

Tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of clonazepam occurs in both animals and humans. In humans, tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of clonazepam occurs frequently.[76][77] Chronic use of benzodiazepines can lead to the development of tolerance with a decrease of benzodiazepine binding sites. The degree of tolerance is more pronounced with clonazepam than with chlordiazepoxide.[78] In general, short-term therapy is more effective than long-term therapy with clonazepam for the treatment of epilepsy.[79] Many studies have found that tolerance develops to the anticonvulsant properties of clonazepam with chronic use, which limits its long-term effectiveness as an anticonvulsant.[80]

Abrupt or over-rapid withdrawal from clonazepam may result in the development of the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, causing psychosis characterised by dysphoric manifestations, irritability, aggressiveness, anxiety, and hallucinations.[81][82][83] Sudden withdrawal may also induce the potentially life-threatening condition, status epilepticus. Anti-epileptic drugs, benzodiazepines such as clonazepam in particular, should be reduced in dose slowly and gradually when discontinuing the drug to mitigate withdrawal effects.[61] Carbamazepine has been tested in the treatment of clonazepam withdrawal but was found to be ineffective in preventing clonazepam withdrawal-induced status epilepticus from occurring.[84]

Overdose

Excess doses may result in:

- Difficulty staying awake

- Mental confusion

- Nausea

- Impaired motor functions

- Impaired reflexes

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired balance

- Dizziness

- Respiratory depression

- Low blood pressure

- Coma

Coma can be cyclic, with the individual alternating from a comatose state to a hyper-alert state of consciousness, which occurred in a four-year-old boy who suffered an overdose of clonazepam.[85] The combination of clonazepam and certain barbiturates (for example, amobarbital), at prescribed doses has resulted in a synergistic potentiation of the effects of each drug, leading to serious respiratory depression.[86]

Overdose symptoms may include extreme drowsiness, confusion, muscle weakness, and fainting.[87]

Detection in biological fluids

Clonazepam and 7-aminoclonazepam may be quantified in plasma, serum, or whole blood in order to monitor compliance in those receiving the drug therapeutically. Results from such tests can be used to confirm the diagnosis in potential poisoning victims or to assist in the forensic investigation in a case of fatal overdosage. Both the parent drug and 7-aminoclonazepam are unstable in biofluids, and therefore specimens should be preserved with sodium fluoride, stored at the lowest possible temperature and analyzed quickly to minimize losses.[88]

Special precautions

The elderly metabolize benzodiazepines more slowly than younger people and are also more sensitive to the effects of benzodiazepines, even at similar blood plasma levels. Doses for the elderly are recommended to be about half of that given to younger adults and are to be administered for no longer than two weeks. Long-acting benzodiazepines such as clonazepam are not generally recommended for the elderly due to the risk of drug accumulation.[10]

The elderly are especially susceptible to increased risk of harm from motor impairments and drug accumulation side effects. Benzodiazepines also require special precaution if used by individuals that may be pregnant, alcohol- or drug-dependent, or may have comorbid psychiatric disorders.[89] Clonazepam is generally not recommended for use in elderly people for insomnia due to its high potency relative to other benzodiazepines.[90]

Clonazepam is not recommended for use in those under 18. Use in very young children may be especially hazardous. Of anticonvulsant drugs, behavioural disturbances occur most frequently with clonazepam and phenobarbital.[89][91]

Doses higher than 0.5–1 mg per day are associated with significant sedation.[92]

Clonazepam may aggravate hepatic porphyria.[93][94]

Clonazepam is not recommended for patients with chronic schizophrenia. A 1982 double-blinded, placebo-controlled study found clonazepam increases violent behavior in individuals with chronic schizophrenia.[95]

Clonazepam has similar effectiveness to other benzodiazepines at often a lower dose.[96]

Pregnancy

There is some medical evidence of various malformations, (for example, cardiac or facial deformations when used in early pregnancy); however, the data is not conclusive. The data are also inconclusive on whether benzodiazepines such as clonazepam cause developmental deficits or decreases in IQ in the developing fetus when taken by the mother during pregnancy. Clonazepam, when used late in pregnancy, may result in the development of a severe benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome in the neonate. Withdrawal symptoms from benzodiazepines in the neonate may include hypotonia, apnoeic spells, cyanosis, and impaired metabolic responses to cold stress.[97]

The safety profile of clonazepam during pregnancy is less clear than that of other benzodiazepines, and if benzodiazepines are indicated during pregnancy, chlordiazepoxide and diazepam may be a safer choice. The use of clonazepam during pregnancy should only occur if the clinical benefits are believed to outweigh the clinical risks to the fetus. Caution is also required if clonazepam is used during breastfeeding. Possible adverse effects of use of benzodiazepines such as clonazepam during pregnancy include: miscarriage, malformation, intrauterine growth retardation, functional deficits, carcinogenesis, and mutagenesis. Neonatal withdrawal syndrome associated with benzodiazepines include hypertonia, hyperreflexia, restlessness, irritability, abnormal sleep patterns, inconsolable crying, tremors, or jerking of the extremities, bradycardia, cyanosis, suckling difficulties, apnea, risk of aspiration of feeds, diarrhea and vomiting, and growth retardation. This syndrome can develop between three days to three weeks after birth and can have a duration of up to several months. The pathway by which clonazepam is metabolized is usually impaired in newborns. If clonazepam is used during pregnancy or breastfeeding, it is recommended that serum levels of clonazepam are monitored and that signs of central nervous system depression and apnea are also checked for. In many cases, non-pharmacological treatments, such as relaxation therapy, psychotherapy, and avoidance of caffeine, can be an effective and safer alternative to the use of benzodiazepines for anxiety in pregnant women.[98]

Interactions

Clonazepam decreases the levels of carbamazepine,[99][100] and, likewise, clonazepam's level is reduced by carbamazepine. Azole antifungals, such as ketoconazole, may inhibit the metabolism of clonazepam.[10] Clonazepam may affect levels of phenytoin (diphenylhydantoin).[99][101][102][103] In turn, Phenytoin may lower clonazepam plasma levels by increasing the speed of clonazepam clearance by approximately 50% and decreasing its half-life by 31%.[104] Clonazepam increases the levels of primidone[102] and phenobarbital.[105]

Combined use of clonazepam with certain antidepressants, anticonvulsants (such as phenobarbital, phenytoin, and carbamazepine), sedative antihistamines, opiates, and antipsychotics, nonbenzodiazepines (such as zolpidem), and alcohol may result in enhanced sedative effects.[10]

Mechanism of action

Clonazepam enhances the activity of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA in the central nervous system to give its anticonvulsant, skeletal muscle relaxant, and anxiolytic effects.[106] It acts by binding to the benzodiazepine site of the GABA receptors, which enhances the electric effect of GABA binding on neurons, resulting in an increased influx of chloride ions into the neurons. This further results in an inhibition of synaptic transmission across the central nervous system.[107][108]

Benzodiazepines do not have any effect on the levels of GABA in the brain.[109] Clonazepam has no effect on GABA levels and has no effect on gamma-aminobutyric acid transaminase. Clonazepam does, however, affect glutamate decarboxylase activity. It differs from other anticonvulsant drugs it was compared to in a study.[110]

Clonazepam's primary mechanism of action is the modulation of GABA function in the brain, by the benzodiazepine receptor, located on GABAA receptors, which, in turn, leads to enhanced GABAergic inhibition of neuronal firing. Benzodiazepines do not replace GABA, but instead enhance the effect of GABA at the GABAA receptor by increasing the opening frequency of chloride ion channels, which leads to an increase in GABA's inhibitory effects and resultant central nervous system depression.[10] In addition, clonazepam decreases the utilization of 5-HT (serotonin) by neurons[111][112] and has been shown to bind tightly to central-type benzodiazepine receptors.[113] Because clonazepam is effective in low milligram doses (0.5 mg clonazepam = 10 mg diazepam),[114][115] it is said to be among the class of "highly potent" benzodiazepines.[116] The anticonvulsant properties of benzodiazepines are due to the enhancement of synaptic GABA responses, and the inhibition of sustained, high-frequency repetitive firing.[117]

Benzodiazepines, including clonazepam, bind to mouse glial cell membranes with high affinity.[118][119] Clonazepam decreases release of acetylcholine in the feline brain[120] and decreases prolactin release in rats.[121] Benzodiazepines inhibit cold-induced thyroid-stimulating hormone (also known as TSH or thyrotropin) release.[122] Benzodiazepines acted via micromolar benzodiazepine binding sites as Ca2+ channel blockers and significantly inhibit depolarization-sensitive calcium uptake in experimentation on rat brain cell components. This has been conjectured as a mechanism for high-dose effects on seizures in the study.[123]

Clonazepam is a 2'-chlorinated derivative of nitrazepam, which increases its potency due to electron-attracting effect of the halogen in the ortho-position.[124][6]

Pharmacokinetics

Clonazepam is lipid-soluble, rapidly crosses the blood–brain barrier, and penetrates the placenta. It is extensively metabolised into pharmacologically inactive metabolites, with only 2% of the unchanged drug excreted in the urine.[125] Clonazepam is metabolized extensively via nitroreduction by cytochrome P450 enzymes, including CYP3A4. Erythromycin, clarithromycin, ritonavir, itraconazole, ketoconazole, nefazodone, cimetidine, and grapefruit juice are inhibitors of CYP3A4 and can affect the metabolism of benzodiazepines.[126] It has an elimination half-life of 19–60 hours.[10] Peak blood concentrations of 6.5–13.5 ng/mL were usually reached within 1–2 hours following a single 2 mg oral dose of micronized clonazepam in healthy adults. In some individuals, however, peak blood concentrations were reached at 4–8 hours.[127]

Clonazepam passes rapidly into the central nervous system, with levels in the brain corresponding with levels of unbound clonazepam in the blood serum.[128] Clonazepam plasma levels are very unreliable amongst patients. Plasma levels of clonazepam can vary as much as tenfold between different patients.[129]

Clonazepam has plasma protein binding of 85%.[130][125] Clonazepam passes through the blood–brain barrier easily, with blood and brain levels corresponding equally with each other.[131] The metabolites of clonazepam include 7-aminoclonazepam, 7-acetaminoclonazepam and 3-hydroxy clonazepam.[8][132] These metabolites are excreted by the kidney.[125]

It is effective for 6–8 hours in children, and 6–12 in adults.[133]

Society and culture

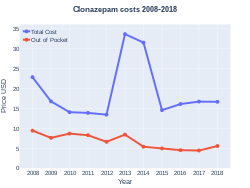

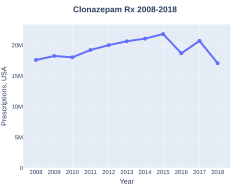

Cost

The wholesale cost in the developing world is between US$0.01 and US$0.07 per pill.[14] In the United States, the pills are about US$0.40 each.[2] In 2017, it was the 34th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 20 million prescriptions.[15][16]

-

Clonazepam costs (US)

-

Clonazepam prescriptions (US)

Recreational use

A 2006 US government study of hospital emergency department (ED) visits found that sedative-hypnotics were the most frequently implicated pharmaceutical drug in visits, with benzodiazepines accounting for the majority of these. Clonazepam was the second most frequently implicated benzodiazepine in ED visits. Alcohol alone was responsible for over twice as many ED visits as clonazepam in the same study. The study examined the number of times the non-medical use of certain drugs was implicated in an ED visit. The criteria for non-medical use in this study were purposefully broad, and include, for example, drug abuse, accidental or intentional overdose, or adverse reactions resulting from legitimate use of the medication.[134]

Formulations

Clonazepam was approved in the United States as a generic drug in 1997 and is now manufactured and marketed by several companies.

Clonazepam is available as tablets and orally disintegrating tablets (wafers) an oral solution (drops), and as a solution for injection or intravenous infusion.[135]

Brand names

It is marketed under the trade name Rivotril by Roche in Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia,[136] Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, China, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Peru, Romania, Serbia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Turkey, and the United States; Emcloz, Linotril and Clonotril in India and other parts of Europe; under the name Riklona in Indonesia and Malaysia; and under the trade name Klonopin by Roche in the United States. Other names, such as Clonoten, Ravotril, Rivotril, Iktorivil, Clonex, Paxam, Petril, Naze, Zilepam and Kriadex, are known throughout the world.[135]

-

Klonopin 0.5 mg tablet

-

Klonopin 1 mg tablet

-

Klonopin 2 mg tablet

-

Clonazepam orally disintegrating tablet, 0.25 mg

References

- ↑ "Clonazepam - Drugs.com". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2017-08-25.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 "Clonazepam". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Clonazepam Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 4 May 2020. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Pagliaro, Ann Marie; Pagliaro, Louis A. (2017). Women's Drug and Substance Abuse: A Comprehensive Analysis and Reflective Synthesis. Routledge. p. PT145. ISBN 9781351618250. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ Hupp, James R.; Tucker, Myron R.; Ellis, Edward (2013). Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 679. ISBN 9780323226875. Archived from the original on 2020-08-12. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Cooper, edited by Grant (2007). Therapeutic uses of botulinum toxin. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press. p. 214. ISBN 9781597452472. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ebel S; Schütz H (February 27, 1977). "[Studies on the detection of clonazepam and its main metabolites considering in particular thin-layer chromatography discrimination of nitrazepam and its major metabolic products (author's transl)]". Arzneimittelforschung. 27 (2): 325–37. PMID 577149.

- ↑ Steentoft, Anni; Linnet, Kristian (30 January 2009). "Blood concentrations of clonazepam and 7-aminoclonazepam in forensic cases in Denmark for the period 2002-2007". Forensic Science International. 184 (1–3): 74–79. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2008.12.004. PMID 19150586.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 10.13 10.14 Riss, J.; Cloyd, J.; Gates, J.; Collins, S. (Aug 2008). "Benzodiazepines in epilepsy: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics" (PDF). Acta Neurol Scand. 118 (2): 69–86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01004.x. PMID 18384456.[dead link]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Dodds, Tyler J. (2017-03-02). "Prescribed Benzodiazepines and Suicide Risk: A Review of the Literature". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 19 (2). doi:10.4088/PCC.16r02037. ISSN 2155-7780. PMID 28257172.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 535. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ Shorter, Edward (2005). "B". A Historical Dictionary of Psychiatry. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190292010. Archived from the original on 2015-10-02.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Clonazepam". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Clonazepam - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ Martino, edited by Davide; Cavanna, Andrea E. (2013). Advances in the neurochemistry and neuropharmacology of Tourette Syndrome. Burlington: Elsevier Science. p. 357. ISBN 9780124115613. Archived from the original on 2015-10-02.

In several countries, prescription and use is now severely limited due to abusive recreational use of clonazepam.

- ↑ Fisher, Gary L. (2009). Encyclopedia of substance abuse prevention, treatment, & recovery. Los Angeles: SAGE. p. 100. ISBN 9781412950848. Archived from the original on 2016-08-12.

frequently abused

- ↑ Rossetti AO; Reichhart MD; Schaller MD; Despland PA; Bogousslavsky J (July 2004). "Propofol treatment of refractory status epilepticus: a study of 31 episodes". Epilepsia. 45 (7): 757–63. doi:10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.01904.x. PMID 15230698.

- ↑ Ståhl Y, Persson A, Petters I, Rane A, Theorell K, Walson P (April 1983). "Kinetics of clonazepam in relation to electroencephalographic and clinical effects". Epilepsia. 24 (2): 225–31. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1983.tb04883.x. PMID 6403345.

- ↑ "Clonazepam: medicine to control seizures or fits, muscle spasms and restless legs syndrome". nhs.uk. 2020-01-06. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- ↑ Dahlin MG, Amark PE, Nergårdh AR (January 2003). "Reduction of seizures with low-dose clonazepam in children with epilepsy". Pediatr. Neurol. 28 (1): 48–52. doi:10.1016/S0887-8994(02)00468-X. PMID 12657420.

- ↑ Hrachovy RA, Frost JD, Kellaway P, Zion TE (October 1983). "Double-blind study of ACTH vs prednisone therapy in infantile spasms". J Pediatr. 103 (4): 641–5. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(83)80606-4. PMID 6312008.

- ↑ Tomson T; Svanborg E, Wedlund JE (May–Jun 1986). "Nonconvulsive status epilepticus: high incidence of complex partial status". Epilepsia. 27 (3): 276–85. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1986.tb03540.x. PMID 3698940.

- ↑ Browne TR (May 1976). "Clonazepam. A review of a new anticonvulsant drug". Arch Neurol. 33 (5): 326–32. doi:10.1001/archneur.1976.00500050012003. PMID 817697.

- ↑ Cloos, Jean-Marc (2005). "The Treatment of Panic Disorder". Curr Opin Psychiatry. 18 (1): 45–50. PMID 16639183. Archived from the original on 2011-04-04. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ↑ Davidson, Jonathan (1993). "Treatment of Social Phobia With Clonazepam and Placebo". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 13 (6): 423–428. doi:10.1097/00004714-199312000-00008. PMID 8120156.

- ↑ Leon, Jose de (2012-03-02). A Practitioner's Guide to Prescribing Antiepileptics and Mood Stabilizers for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4614-2012-5. Archived from the original on 2020-08-12. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ Nardi, AE.; Perna, G. (May 2006). "Clonazepam in the treatment of psychiatric disorders: an update". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 21 (3): 131–42. doi:10.1097/01.yic.0000194379.65460.a6. PMID 16528135. S2CID 29469943.

- ↑ "[Restless legs syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Opinion of Brazilian experts]". Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 65 (3A): 721–7. Sep 2007. doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2007000400035. PMID 17876423.

- ↑ Trenkwalder, C.; Hening, WA.; Montagna, P.; Oertel, WH.; Allen, RP.; Walters, AS.; Costa, J.; Stiasny-Kolster, K.; Sampaio, C. (Dec 2008). "Treatment of restless legs syndrome: an evidence-based review and implications for clinical practice" (PDF). Mov Disord. 23 (16): 2267–302. doi:10.1002/mds.22254. PMID 18925578. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-29. Retrieved 2010-01-19.

- ↑ Huynh, NT.; Rompré, PH.; Montplaisir, JY.; Manzini, C.; Okura, K.; Lavigne, GJ. (2006). "Comparison of various treatments for sleep bruxism using determinants of number needed to treat and effect size". Int J Prosthodont. 19 (5): 435–41. PMID 17323720.

- ↑ Ferini-Strambi, L.; Zucconi, M. (Sep 2000). "REM sleep behavior disorder". Clin Neurophysiol. 111 Suppl 2: S136–40. doi:10.1016/S1388-2457(00)00414-4. PMID 10996567. S2CID 43692512.

- ↑ Nelson, DE (October 2001). ""Akathisia - a brief review." Scottish Medical Journal. Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-03-23. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Horiguchi, J; Nishimatsu, O; Inami, Y (1989). "Successful treatment with clonazepam for neuroleptic-induced akathisia". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 80 (1): 106–107. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb01308.x. PMID 2569804. Archived from the original on 2013-01-05.

- ↑ Lipton, S.A.; Rosenberg, P.A.; Rosenberg, Paul A. (1994). "Excitatory amino acids as a final common pathway for neurological disorders". N. Engl. J. Med. 330 (9): 613–22. doi:10.1056/NEJM199403033300907. PMID 7905600.

- ↑ Bird, RD; Makela, EH (January 1994). "Alcohol withdrawal: what is the benzodiazepine of choice?". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 28 (1): 67–71. doi:10.1177/106002809402800114. PMID 8123967. S2CID 24312761.

- ↑ Curtin F, Schulz P; Schulz (2004). "Clonazepam and lorazepam in acute mania: a Bayesian meta-analysis". J Affect Disord. 78 (3): 201–8. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00317-8. PMID 15013244.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Gillies, Donna; Sampson, Stephanie; Beck, Alison; Rathbone, John (2013-04-30). "Benzodiazepines for psychosis-induced aggression or agitation" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD003079. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003079.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 23633309. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ Zhou, L.; Chillag, KL.; Nigro, MA. (Oct 2002). "Hyperekplexia: a treatable neurogenetic disease". Brain Dev. 24 (7): 669–74. doi:10.1016/S0387-7604(02)00095-5. PMID 12427512. S2CID 40864297.

- ↑ Schenck, CH.; Arnulf, I.; Mahowald, MW. (Jun 2007). "Sleep and Sex: What Can Go Wrong? A Review of the Literature on Sleep Related Disorders and Abnormal Sexual Behaviors and Experiences". Sleep. 30 (6): 683–702. doi:10.1093/sleep/30.6.683. PMC 1978350. PMID 17580590.

- ↑ Mulleners, WM; Chronicle, EP (June 2008). "Anticonvulsants in migraine prophylaxis: a Cochrane review". Cephalalgia : An International Journal of Headache. 28 (6): 585–97. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01571.x. PMID 18454787. S2CID 24233098.

- ↑ Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online) London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press http://www.medicinescomplete.com Archived 2021-06-10 at the Wayback Machine [Accessed on 2nd February 2020]

- ↑ Stacy, M. (2002). "Sleep disorders in Parkinson's disease: epidemiology and management". Drugs Aging. 19 (10): 733–9. doi:10.2165/00002512-200219100-00002. PMID 12390050. S2CID 40376995.

- ↑ Lander CM; Donnan GA; Bladin PF; Vajda FJ (1979). "Some aspects of the clinical use of clonazepam in refractory epilepsy". Clin Exp Neurol. 16: 325–32. PMID 121707.

- ↑ Sorel L; Mechler L; Harmant J (1981). "Comparative trial of intravenous lorazepam and clonazepam im status epilepticus". Clin Ther. 4 (4): 326–36. PMID 6120763.

- ↑ Wollman M; Lavie P; Peled R (1985). "A hypernychthemeral sleep-wake syndrome: a treatment attempt". Chronobiol Int. 2 (4): 277–80. doi:10.3109/07420528509055890. PMID 3870855.

- ↑ Aronson, Jeffrey Kenneth (20 Nov 2008). Meyler's Side Effects of Psychiatric Drugs (Meylers Side Effects). Elsevier Science. p. 403. ISBN 978-0-444-53266-4.

- ↑ "Clonazepam Side Effects". Drugs.com. 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-04-28.

- ↑ The interface of neurology internal medicine. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Wiliams Wilkins. 1 September 2007. p. 963. ISBN 978-0-7817-7906-7. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ↑ The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology (Schatzberg, American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology). USA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. 31 July 2009. p. 471. ISBN 978-1-58562-309-9. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ↑ "Get Some Sleep: Beware the sleeping pill hangover". Archived from the original on 2017-07-21. Retrieved 2017-06-21.

- ↑ Goswami, Meeta; R. Pandi-Perumal, S.; Thorpy, Michael J. (24 Mar 2010). Narcolepsy:: A Clinical Guide. Springer. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-4419-0853-7. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ↑ Kelsey, Jeffrey E.; Newport, D. Jeffrey; Nemeroff, Charles B. (2006). Principles of psychopharmacology for mental health professionals. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Liss. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-471-25401-0. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ Lee-chiong, Teofilo (24 April 2008). Sleep Medicine: Essentials and Review. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 463–465. ISBN 978-0-19-530659-0. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ↑ Trevor, Anthony J.; Katzung, Bertram G.; Masters, Susan B. (1 January 2008). Katzung Trevor's pharmacology: examination board review. New York: McGraw Hill Medical. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-07-148869-3. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ↑ Sjö O; Hvidberg EF; Naestoft J; Lund M (4 April 1975). "Pharmacokinetics and side-effects of clonazepam and its 7-amino-metabolite in man". Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 8 (3–4): 249–54. doi:10.1007/BF00567123. PMID 1233220. S2CID 27095161.

- ↑ Alvarez N; Hartford E; Doubt C (April 1981). "Epileptic seizures induced by clonazepam". Clin Electroencephalogr. 12 (2): 57–65. doi:10.1177/155005948101200203. PMID 7237847. S2CID 39403793.

- ↑ Ishizu T, Chikazawa S, Ikeda T, Suenaga E (July 1988). "[Multiple types of seizure induced by clonazepam in an epileptic patient]". No to Hattatsu (in Japanese). 20 (4): 337–9. PMID 3214607.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Bang F; Birket-Smith E; Mikkelsen B (September 1976). "Clonazepam in the treatment of epilepsy. A clinical long-term follow-up study". Epilepsia. 17 (3): 321–4. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1976.tb03410.x. PMID 824124.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Bruni J (7 April 1979). "Recent advances in drug therapy for epilepsy". Can Med Assoc J (PDF). 120 (7): 817–24. PMC 1818965. PMID 371777.

- ↑ Rosenfeld WE, Beniak TE, Lippmann SM, Loewenson RB (1987). "Adverse behavioral response to clonazepam as a function of Verbal IQ-Performance IQ discrepancy". Epilepsy Res. 1 (6): 347–56. doi:10.1016/0920-1211(87)90059-3. PMID 3504409. S2CID 40893264.

- ↑ White MC; Silverman JJ; Harbison JW (February 1982). "Psychosis associated with clonazepam therapy for blepharospasm". J Nerv Ment Dis. 170 (2): 117–9. doi:10.1097/00005053-198202000-00010. PMID 7057171.

- ↑ Williams A; Gillespie M (July 1979). "Clonazepam-induced incontinence". Ann Neurol. 6 (1): 86. doi:10.1002/ana.410060127. PMID 507767.

- ↑ Sandyk R (August 13, 1983). "Urinary incontinence associated with clonazepam therapy". S Afr Med J. 64 (7): 230. PMID 6879368.

- ↑ Anders RJ; Wang E; Radhakrishnan J; Sharifi R; Lee M (October 1985). "Overflow urinary incontinence due to carbamazepine". J Urol. 134 (4): 758–9. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)47428-3. PMID 4032590.

- ↑ Olsson R, Zettergren L; Zettergren (May 1988). "Anticonvulsant-induced liver damage". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 83 (5): 576–7. PMID 3364416.

- ↑ van der Bijl P, Roelofse JA; Roelofse (1991). "Disinhibitory reactions to benzodiazepines: a review". J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 49 (5): 519–23. doi:10.1016/0278-2391(91)90180-T. PMID 2019899.

- ↑ Cohen LS, Rosenbaum JF; Rosenbaum (October 1987). "Clonazepam: new uses and potential problems". J Clin Psychiatry. 48 Suppl: 50–6. PMID 2889724.

- ↑ Lockard JS; Levy RH; Congdon WC; DuCharme LL; Salonen LD (December 1979). "Clonazepam in a focal-motor monkey model: efficacy, tolerance, toxicity, withdrawal, and management". Epilepsia. 20 (6): 683–95. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1979.tb04852.x. PMID 115680.

- ↑ Vining EP (August 1986). "Use of barbiturates and benzodiazepines in treatment of epilepsy". Neurol Clin. 4 (3): 617–32. doi:10.1016/S0733-8619(18)30966-6. PMID 3528811.

- ↑ Bernik MA; Gorenstein C; Vieira Filho AH (1998). "Stressful reactions and panic attacks induced by flumazenil in chronic benzodiazepine users". Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England). 12 (2): 146–50. doi:10.1177/026988119801200205. PMID 9694026. S2CID 24348950.

- ↑ Stahl, Stephen M. (2014). Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Prescriber's Guide (5th ed.). San Diego, CA: Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-107-67502-5. Archived from the original on 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ Adjeroud, S; Tonon, Mc; Leneveu, E; Lamacz, M; Danger, Jm; Gouteux, L; Cazin, L; Vaudry, H (May 1987). "The benzodiazepine agonist clonazepam potentiates the effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid on alpha-MSH release from neurointermediate lobes in vitro". Life Sciences. 40 (19): 1881–7. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(87)90046-4. PMID 3033417.

- ↑ Yokota, K; Tatebayashi, H; Matsuo, T; Shoge, T; Motomura, H; Matsuno, T; Fukuda, A; Tashiro, N (March 2002). "The effects of neuroleptics on the GABA-induced Cl− current in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons: differences between some neuroleptics". British Journal of Pharmacology. 135 (6): 1547–55. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704608. PMC 1573270. PMID 11906969.

- ↑ Loiseau P (1983). "[Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy]". Encephale. 9 (4 Suppl 2): 287B–292B. PMID 6373234.

- ↑ Scherkl R, Scheuler W, Frey HH (December 1985). "Anticonvulsant effect of clonazepam in the dog: development of tolerance and physical dependence". Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 278 (2): 249–60. PMID 4096613.

- ↑ Crawley JN; Marangos PJ; Stivers J; Goodwin FK (January 1982). "Chronic clonazepam administration induces benzodiazepine receptor subsensitivity". Neuropharmacology. 21 (1): 85–9. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(82)90216-7. PMID 6278355. S2CID 24771398.

- ↑ Bacia T; Purska-Rowińska E; Okuszko S (1980). "Clonazepam in the treatment of drug-resistant epilepsy: a clinical short- and long-term follow-up study". Monographs in Neural Sciences. Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience. 5: 153–9. doi:10.1159/000387498. ISBN 978-3-8055-0635-9. PMID 7033770.

- ↑ Browne TR (May 1976). "Clonazepam. A review of a new anticonvulsant drug". Arch Neurol. 33 (5): 326–32. doi:10.1001/archneur.1976.00500050012003. PMID 817697.

- ↑ Sironi VA; Miserocchi G; De Riu PL (April 1984). "Clonazepam withdrawal syndrome". Acta Neurol (Napoli). 6 (2): 134–9. PMID 6741654.

- ↑ Sironi VA; Franzini A; Ravagnati L; Marossero F (August 1979). "Interictal acute psychoses in temporal lobe epilepsy during withdrawal of anticonvulsant therapy". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 42 (8): 724–30. doi:10.1136/jnnp.42.8.724. PMC 490305. PMID 490178.

- ↑ Jaffe R; Gibson E (June 1986). "Clonazepam withdrawal psychosis". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 6 (3): 193. doi:10.1097/00004714-198606000-00021. PMID 3711371.

- ↑ Sechi GP; Zoroddu G; Rosati G (September 1984). "Failure of carbamazepine to prevent clonazepam withdrawal statusepilepticus". Ital J Neurol Sci. 5 (3): 285–7. doi:10.1007/BF02043959. PMID 6500901. S2CID 23094043.

- ↑ Welch TR; Rumack BH; Hammond K (1977). "Clonazepam overdose resulting in cyclic coma". Clin Toxicol. 10 (4): 433–6. doi:10.3109/15563657709046280. PMID 862377.

- ↑ Honer WG; Rosenberg RG; Turey M; Fisher WA (November 1986). "Respiratory failure after clonazepam and amobarbital". Am J Psychiatry. 143 (11): 1495. doi:10.1176/ajp.143.11.1495b. PMID 3777263.

- ↑ "Clonazepam, Prescription Marketed Drugs". Archived from the original on 2012-04-25.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 335-337.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, AA.; Vennat, B.; Llorca, PM.; Eschalier, A. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Ann Pharm Fr. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- ↑ Wolkove, N.; Elkholy, O.; Baltzan, M.; Palayew, M. (May 2007). "Sleep and aging: 2. Management of sleep disorders in older people". CMAJ. 176 (10): 1449–54. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070335. PMC 1863539. PMID 17485699.

- ↑ Trimble MR; Cull C (1988). "Children of school age: the influence of antiepileptic drugs on behavior and intellect". Epilepsia. 29 Suppl 3: S15–9. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1988.tb05805.x. PMID 3066616.

- ↑ Hollister LE (1975). "Dose-ranging studies of clonazepam in man". Psychopharmacol Commun. 1 (1): 89–92. PMID 1223993.

- ↑ Bonkowsky HL; Sinclair PR; Emery S; Sinclair JF (June 1980). "Seizure management in acute hepatic porphyria: risks of valproate and clonazepam". Neurology. 30 (6): 588–92. doi:10.1212/WNL.30.6.588. PMID 6770287. S2CID 21137619.

- ↑ Reynolds NC Jr; Miska RM (April 1981). "Safety of anticonvulsants in hepatic porphyrias". Neurology. 31 (4): 480–4. doi:10.1212/wnl.31.4.480. PMID 7194443.

- ↑ Karson CN; Weinberger DR; Bigelow L; Wyatt RJ (December 1982). "Clonazepam treatment of chronic schizophrenia: negative results in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Am J Psychiatry. 139 (12): 1627–8. doi:10.1176/ajp.139.12.1627. PMID 6756174.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine Equivalency Table: Benzodiazepine Equivalency". 28 April 2017. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ↑ McElhatton PR (1994). "The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation". Reprod Toxicol. 8 (6): 461–75. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9. PMID 7881198.

- ↑ Iqbal, MM.; Sobhan, T.; Ryals, T. (Jan 2002). "Effects of commonly used benzodiazepines on the fetus, the neonate, and the nursing infant". Psychiatr Serv. 53 (1): 39–49. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.1.39. PMID 11773648. Archived from the original on 2003-07-11.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Lander CM; Eadie MJ; Tyrer JH (1975). "Interactions between anticonvulsants". Proc Aust Assoc Neurol. 12: 111–6. PMID 2912.

- ↑ Pippenger CE (1987). "Clinically significant carbamazepine drug interactions: an overview". Epilepsia. 28 (Suppl 3): S71–6. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1987.tb05781.x. PMID 3319544.

- ↑ Saavedra IN; Aguilera LI; Faure E; Galdames DG (August 1985). "Phenytoin/clonazepam interaction". Ther Drug Monit. 7 (4): 481–4. doi:10.1097/00007691-198512000-00022. PMID 4082246.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Windorfer A Jr; Sauer W (1977). "Drug interactions during anticonvulsant therapy in childhood: diphenylhydantoin, primidone, phenobarbitone, clonazepam, nitrazepam, carbamazepin and dipropylacetate". Neuropadiatrie. 8 (1): 29–41. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1091502. PMID 321985.

- ↑ Windorfer A; Weinmann HM; Stünkel S (March 1977). "[Laboratory controls in long-term treatment with anticonvulsive drugs (author's transl)]". Monatsschr Kinderheilkd. 125 (3): 122–8. PMID 323695.

- ↑ Khoo KC; Mendels J; Rothbart M; Garland WA; Colburn WA; Min BH; Lucek R; Carbone JJ; Boxenbaum HG; Kaplan SA (September 1980). "Influence of phenytoin and phenobarbital on the disposition of a single oral dose of clonazepam". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 28 (3): 368–75. doi:10.1038/clpt.1980.175. PMID 7408397.

- ↑ Bendarzewska-Nawrocka B; Pietruszewska E; Stepień L; Bidziński J; Bacia T (1980). "[Relationship between blood serum luminal and diphenylhydantoin level and the results of treatment and other clinical data in drug-resistant epilepsy]". Neurol Neurochir Pol. 14 (1): 39–45. PMID 7374896.

- ↑ "FDA clonazepam" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ↑ Skerritt JH; Johnston GA (May 6, 1983). "Enhancement of GABA binding by benzodiazepines and related anxiolytics". Eur J Pharmacol. 89 (3–4): 193–8. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(83)90494-6. PMID 6135616.

- ↑ Lehoullier PF, Ticku MK; Ticku (March 1987). "Benzodiazepine and beta-carboline modulation of GABA-stimulated 36Cl-influx in cultured spinal cord neurons". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 135 (2): 235–8. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(87)90617-0. PMID 3034628.

- ↑ Varotto M; Roman G; Battistin L (30 April 1981). "[Pharmacological influences on the brain level and transport of GABA. I) Effect of various antiepileptic drugs on brain levels of GABA]". Boll Soc Ital Biol Sper. 57 (8): 904–8. PMID 7272065.

- ↑ Battistin L, Varotto M, Berlese G, Roman G (1984). "Effects of some anticonvulsant drugs on brain GABA level and GAD and GABA-T activities". Neurochem. Res. 9 (2): 225–31. doi:10.1007/BF00964170. PMID 6429560. S2CID 34328063.

- ↑ Meldrum BS (1986). "Drugs acting on amino acid neurotransmitters". Adv Neurol. 43: 687–706. PMID 2868623.

- ↑ Jenner P; Pratt JA; Marsden CD (1986). "Mechanism of action of clonazepam in myoclonus in relation to effects on GABA and 5-HT". Adv Neurol. 43: 629–43. PMID 2418652.

- ↑ Gavish M; Fares F (November 1985). "Solubilization of peripheral benzodiazepine-binding sites from rat kidney" (PDF). J Neurosci. 5 (11): 2889–93. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-11-02889.1985. PMC 6565154. PMID 2997409.

- ↑ "Benzodiazepine Equivalency Table" based on NRHA Drug Newsletter, April 1985 and Benzodiazepines: How they Work & How to Withdraw (The Ashton Manual), 2002.[1] Archived 2020-07-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "What are the equivalent doses of oral benzodiazepines?". SPS - Specialist Pharmacy Service. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- ↑ Chouinard G (2004). "Issues in the clinical use of benzodiazepines: potency, withdrawal, and rebound". J Clin Psychiatry. 65 Suppl 5: 7–12. PMID 15078112.

- ↑ Macdonald RL; McLean MJ (1986). "Anticonvulsant drugs: mechanisms of action". Adv Neurol. 44: 713–36. PMID 2871724.

- ↑ Tardy M; Costa MF; Rolland B; Fages C; Gonnard P. (April 1981). "Benzodiazepine receptors on primary cultures of mouse astrocytes". J Neurochem. 36 (4): 1587–9. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1981.tb00603.x. PMID 6267195.

- ↑ Gallager DW; Mallorga P; Oertel W; Henneberry R; Tallman J (February 1981). "{3H}Diazepam binding in mammalian central nervous system: a pharmacological characterization". J Neurosci (PDF). 1 (2): 218–25. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-02-00218.1981. PMC 6564145. PMID 6267221. Archived from the original on 2008-01-02.

- ↑ Petkov V; Georgiev VP; Getova D; Petkov VV (1982). "Effects of some benzodiazepines on the acetylcholine release in the anterior horn of the lateral cerebral ventricle of the cat". Acta Physiol Pharmacol Bulg. 8 (3): 59–66. PMID 6133407.

- ↑ Grandison L (1982). "Suppression of prolactin secretion by benzodiazepines in vivo". Neuroendocrinology. 34 (5): 369–73. doi:10.1159/000123330. PMID 6979001.

- ↑ Camoratto AM; Grandison L (18 April 1983). "Inhibition of cold-induced TSH release by benzodiazepines". Brain Res. 265 (2): 339–43. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(83)90353-0. PMID 6405978. S2CID 5520697.

- ↑ Taft WC; DeLorenzo RJ (May 1984). "Micromolar-affinity benzodiazepine receptors regulate voltage-sensitive calcium channels in nerve terminal preparations" (PDF). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (PDF). 81 (10): 3118–22. Bibcode:1984PNAS...81.3118T. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.10.3118. PMC 345232. PMID 6328498. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-06-25.

- ↑ Shorvon, Simon; Perucca, Emilio; Fish, David; Dodson, W. E. (2008). The Treatment of Epilepsy. John Wiley & Sons. p. 366. ISBN 9780470752456. Archived from the original on 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 125.2 "Clonazepam". www.drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ↑ Dresser, G.K.; Spence, J.D.; Bailey, D.G. (2000). "Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic consequences and clinical relevance of cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition". Clin. Pharmacokinet. 38 (1): 41–57. doi:10.2165/00003088-200038010-00003. PMID 10668858. S2CID 37743328.

- ↑ "Monograph - Clonazepam -- Pharmacokinetics". Medscape. January 2006. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ↑ Parry GJ (1976). "An animal model for the study of drugs in the central nervous system". Proc Aust Assoc Neurol. 13: 83–8. PMID 1029011.

- ↑ Gerna M; Morselli PL (January 21, 1976). "A simple and sensitive gas chromatographic method for the determination of clonazepam in human plasma". J Chromatogr. 116 (2): 445–50. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)89915-X. PMID 1245581.

- ↑ Tokola RA; Neuvonen PJ (1983). "Pharmacokinetics of antiepileptic drugs". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica Supplementum. 97: 17–27. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1983.tb01532.x. PMID 6143468.

- ↑ Greenblatt DJ, Miller LG, Shader RI (October 1987). "Clonazepam pharmacokinetics, brain uptake, and receptor interactions". J Clin Psychiatry. 48 Suppl: 4–11. PMID 2822672.

- ↑ Edelbroek PM; De Wolff FA (October 1978). "Improved micromethod for determination of underivatized clonazepam in serum by gas chromatography" (PDF). Clinical Chemistry (PDF). 24 (10): 1774–7. doi:10.1093/clinchem/24.10.1774. PMID 699288. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-07.

- ↑ Cooper, Grant (2007-10-05). Therapeutic Uses of Botulinum Toxin. ISBN 9781597452472. Archived from the original on 2020-08-12. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ "Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2006: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2006. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 9 February 2009.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 "Clonazepam." In Buckingham R (ed), Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. [online] London: Pharmaceutical Press http://www.medicinescomplete.com Archived 2021-06-10 at the Wayback Machine (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- ↑ "Register of Medicinal Products". ravimiregister.ravimiamet.ee. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

Further reading

- Poisons Information Monograph - Clonazepam Archived 2010-03-28 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from February 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- CS1: long volume value

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chem-molar-mass both hardcoded and calculated

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from December 2015

- All Wikipedia articles needing clarification

- Wikipedia articles needing clarification from February 2014

- Chloroarenes

- Euphoriants

- GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators

- Glycine receptor antagonists

- Hoffmann-La Roche brands

- Genentech brands

- Lactams

- Nitrobenzodiazepines

- RTT