Pseudoephedrine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌsuːdoʊ.ɪˈfɛdrɪn, -ˈɛfɪdriːn/ |

| Trade names | Afrinol, Sudafed, Sinutab, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Sympathomimetic (alpha and beta adrenergic agonist)[1][2] |

| Main uses | Congestion of the nose[1] |

| Side effects | Trouble sleeping, palpitations, headache, dizziness[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682619 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | ~100%[3] |

| Metabolism | 10–30% liver |

| Elimination half-life | 4.3–8 hours[3] |

| Excretion | 43–96% kidney[3] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

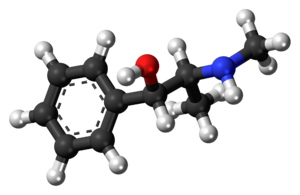

| Formula | C10H15NO |

| Molar mass | 165.23 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Pseudoephedrine (PSE) is a medication used for congestion of the nose such as may occur from hay fever or the common cold.[1] It may also be used to prevent pressure related ear problems due to eustachian tube obstruction.[1] It has not been found to be useful for sinusitis.[1] Use is not recommended in children less than six.[2] It is sold both by itself and over-the-counter in combination with other active ingredients such as antihistamines, guaifenesin, dextromethorphan, paracetamol (acetaminophen), or NSAIDs.[1][2] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include trouble sleeping, palpitations, headache, and dizziness.[1] Other concerns include abuse.[1] Use in early pregnancy is associated with harm to the baby well use during the early part of breastfeeding may reduce milk output.[2] It is a sympathomimetic and alpha and beta adrenergic agonist.[1][2]

Pseudoephedrine was isolated in 1889, by the German chemists Ladenburg and Oelschlägel, from Ephedra vulgaris at the Merck pharmaceutical company.[4][5] Plants that contain the medication; however, have been used in Chinese medicine for 5,000 years.[5] At higher doses it is used as a wakefulness-promoting agent and to enhance athletic performance.[6] Such use, has at various times, not been permitted by the International Olympic Committee.[6] Pseudoephedrine has also been used to illegally manufacture methamphetamines.[1] In the United Kingdom 24 tabs of 60 mg costs the NHS about 2 pounds.[2]

Medical uses

Pseudoephedrine is a stimulant, but it is well known for shrinking swollen nasal mucous membranes, so it is often used as a decongestant. It reduces tissue hyperemia, edema, and nasal congestion commonly associated with colds or allergies. Other beneficial effects may include increasing the drainage of sinus secretions, and opening of obstructed Eustachian tubes. The same vasoconstriction action can also result in hypertension, which is a noted side effect of pseudoephedrine.

Pseudoephedrine can be used either as oral or as topical decongestant. However, due to its stimulating qualities, the oral preparation is more likely to cause adverse effects, including urinary retention.[7][8] According to one study, pseudoephedrine may show effectiveness as an antitussive drug (suppression of cough).[9]

Pseudoephedrine is used for the treatment of nasal congestion, sinus congestion and Eustachian tube congestion.[10] Pseudoephedrine is also used for vasomotor rhinitis, and as an adjunct to other agents in the optimum treatment of allergic rhinitis, croup, sinusitis, otitis media, and tracheobronchitis.[10]

Pseudoephedrine is also used as a first-line preventative treatment for recurrent priapism. Erection is largely a parasympathetic response, so the sympathetic action of pseudoephedrine may serve to relieve this condition. Treatment for urinary incontinence is an off-label use.[11]

Dosage

The typical dose in those over 11 years of age is is 60 mg three to four times per day.[2] In those who are 6 to 11 the dose is half that.[2]

Side effects

Common side effects include central nervous system stimulation, insomnia, nervousness, excitability, dizziness and anxiety. Infrequent side effects include tachycardia or palpitations. Rarely, pseudoephedrine therapy may be associated with mydriasis (dilated pupils), hallucinations, arrhythmias, hypertension, seizures and ischemic colitis;[12] as well as severe skin reactions known as recurrent pseudo-scarlatina, systemic contact dermatitis, and nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption.[13] Pseudoephedrine, particularly when combined with other drugs including narcotics, may also play a role in the precipitation of episodes of paranoid psychosis.[14] It has also been reported that pseudoephedrine, among other sympathomimetic agents, may be associated with the occurrence of stroke.[15]

Precautions

Pseudoephedrine is contraindicated in patients with diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, severe or uncontrolled hypertension, severe coronary artery disease, prostatic hypertrophy, hyperthyroidism, closed angle glaucoma, or by pregnant women.[12] The safety and effectiveness of nasal decongestant use in children is unclear.[16]

Interactions

Concomitant or recent (previous fourteen days) monoamine oxidase inhibitor use can lead to hypertensive reactions, including hypertensive crises.[12]

The antihypertensive effects of methyldopa, mecamylamine, reserpine and veratrum alkaloids may be reduced by sympathomimetics. Beta-adrenergic antagonists may also interact with sympathomimetics. Increase of ectopic pacemaker activity can occur when pseudoephedrine is used concomitantly with digitalis. Antacids increase the rate of pseudoephedrine absorption, while kaolin decreases it.[citation needed]

Mechanism of action

Pseudoephedrine is a sympathomimetic amine. Its principal mechanism of action relies on its direct action on the adrenergic receptor system.[17][18] The vasoconstriction that pseudoephedrine produces is believed to be principally an α-adrenergic receptor response.[19]

Pseudoephedrine acts on α- and β2-adrenergic receptors, to cause vasoconstriction and relaxation of smooth muscle in the bronchi, respectively.[17][18] α-Adrenergic receptors are located on the muscles lining the walls of blood vessels. When these receptors are activated, the muscles contract, causing the blood vessels to constrict (vasoconstriction). The constricted blood vessels now allow less fluid to leave the blood vessels and enter the nose, throat and sinus linings, which results in decreased inflammation of nasal membranes, as well as decreased mucus production. Thus, by constriction of blood vessels, mainly those located in the nasal passages, pseudoephedrine causes a decrease in the symptoms of nasal congestion. Activation of β2-adrenergic receptors produces relaxation of smooth muscle of the bronchi,[17] causing bronchial dilation and in turn decreasing congestion (although not fluid) and difficulty breathing.

Chemistry

Pseudoephedrine is a diastereomer of ephedrine and is readily reduced into methamphetamine or oxidized into methcathinone.

Nomenclatures

The dextrorotary (+)- or d- enantiomer is (1S,2S)-pseudoephedrine, whereas the levorotating (−)- or l- form is (1R,2R)-pseudoephedrine.

In the outdated D/L system (+)-pseudoephedrine is also referred to as L-pseudoephedrine and (−)-pseudoephedrine as D-pseudoephedrine (in the Fisher projection then the phenyl ring is drawn at bottom).[20][21]

Often the D/L system (with small caps) and the d/l system (with lower-case) are confused. The result is that the dextrorotary d-pseudoephedrine is wrongly named D-pseudoephedrine and the levorotary l-ephedrine (the diastereomer) wrongly L-ephedrine.

The IUPAC names of the two enantiomers are (1S,2S)- respectively (1R,2R)-2-methylamino-1-phenylpropan-1-ol. Synonyms for both are psi-ephedrine and threo-ephedrine.

Pseudoephedrine is the International Nonproprietary Name of the (+)-form, when used as pharmaceutical substance.[22]

Society and culture

Cost

The U.S. cost of 30 mg is $11 USD for 24 tablets of pseudoephedrine[23]

-

Pseudoephedrine costs (US)

-

Pseudoephedrine prescriptions (US)

Brand names

The following is a list of consumer medicines that either contain pseudoephedrine or have switched to an alternative such as phenylephrine.

- Actifed (made by GlaxoSmithKline) — contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine and 2.5 mg triprolidine in certain countries.

- Advil Cold & Sinus (made by Pfizer Canada Inc.) — contains 30 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and 200 mg Ibuprofen.

- Aleve-D Sinus & Cold (made by Bayer Healthcare) — contains 120 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 220 mg naproxen).

- Allegra D (made by Sanofi Aventis) — contains 120 mg of pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 60 mg of fexofenadine).

- Allerclear-D (made by Kirkland Signature) — contains 240 mg of pseudoephedrine sulfate (also 10 mg of loratadine).

- Benadryl Plus (made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a Johnson & Johnson company) — contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 8 mg acrivastine)

- Cirrus (made by UCB) — contains 120 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 5 mg cetirizine).

- Claritin-D (made by Bayer Healthcare) — contains 120 mg of pseudoephedrine sulfate (also 5 mg of loratadine).

- Claritin-D 24 Hour (made by Bayer Healthcare) — contains 240 mg of pseudoephedrine sulfate (also 10 mg of loratadine).

- Codral (made by Asia-Pacific subsidiary of Johnson & Johnson) — Codral Original contains pseudoephedrine, Codral New Formula substitutes phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine.

- Congestal (made by SIGMA Pharmaceutical Industries) — contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 650 mg paracetamol and 4 mg chlorpheniramine).[24][25]

- Contac (made by GlaxoSmithKline) — previously contained pseudoephedrine, now contains phenylephrine. As at Nov 2014 UK version still contains 30 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride per tablet.

- Demazin (made by Bayer Healthcare) — contains pseudoephedrine sulfate and chlorpheniramine maleate

- Eltor (made by Sanofi Aventis) — contains pseudoephedrine hydrochloride.

- Mucinex D (made by Reckitt Benckiser) — contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 1200 mg guaifenesin).

- Nexafed (made by Acura Pharmaceuticals) — contains 30 mg pseudoephedrine per tablet, formulated with Impede Meth-Deterrent technology.

- Nurofen Cold & Flu (made by Reckitt Benckiser) — contains 30 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 200 mg ibuprofen).

- Respidina – contains 120 mg of pseudoephedrine in the form of extended release tablets.

- Rhinex Flash (made by Pharma Product Manufacturing, Cambodia) — contains pseudoephedrine combined with paracetamol and triprolidine.

- Rhinos SR (made by Dexa Medica) — contains 120 mg of pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 5 mg loratadine).

- Rino-Ebastel (made by Almirall) – contains 120 mg of pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 10 mg ebastine).

- Sinufed (made by Trima) — contains 60 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride.

- Sinutab (made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a Johnson & Johnson company) — contains 500 mg paracetamol and 30 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride.

- Sudafed Decongestant (made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a Johnson & Johnson company) — contains 60 mg of pseudoephedrine hydrochloride.

- Theraflu (made by Novartis) — previously contained pseudoephedrine, now contains phenylephrine.

- Unifed (made by United Pharmaceutical Manufacturer, Jordan) — contains pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also triprolidine and guaifenesin).

- Zyrtec-D 12 Hour (made by McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a Johnson & Johnson company) — contains 120 mg pseudoephedrine hydrochloride (also 5 mg of cetirizine).

- Zephrex-D (made by Westport Pharmaceuticals) - a special meth-resistant form of pseudoephedrine that becomes gooey when heated

Legal status

Australia

Illicit diversion of pseudoephedrine in Australia has caused significant changes to the way the products are regulated. As of 2006[update], all products containing pseudoephedrine have been rescheduled as either "Pharmacist Only Medicines" (Schedule 3) or "Prescription Only Medicines" (Schedule 4), depending on the amount of pseudoephedrine in the product. A Pharmacist Only Medicine may only be sold to the public if a pharmacist is directly involved in the transaction. These medicines must be kept behind the counter, away from public access.

Pharmacists are also encouraged (and in some states required) to log purchases with the online database Project STOP.[26] This system aims to prevent individuals from purchasing small quantities of pseudoephedrine from many different pharmacies.

As a result, many pharmacies no longer stock Sudafed, the common brand of pseudoephedrine cold/sinus tablets, opting instead to sell Sudafed PE, a phenylephrine product which has not been proven effective in clinical trials.[27][28][29]

Canada

Health Canada has investigated the risks and benefits of pseudoephedrine and ephedrine/ephedra. Near the end of the study, Health Canada issued a warning on their website stating that those who are under the age of 12, or who have heart disease and may suffer from strokes, should avoid taking pseudoephedrine and ephedrine. Also, they warned that everyone should avoid taking ephedrine or pseudoephrine with other stimulants like caffeine. They also banned all products that contain both ephedrine (or pseudoephedrine) and caffeine.[30]

Products whose only medicinal ingredient is pseudoephedrine must be kept behind the pharmacy counter. Products containing pseudoephedrine along with other medicinal ingredients may be displayed on store shelves but may be sold only in a pharmacy when a pharmacist is present.[31][32]

Colombia

The Colombian government prohibited the trade of pseudoephedrine in 2010.[33]

Japan

Medications that contain more than 10% pseudoephedrine are prohibited under the Stimulants Control Law in Japan.[34]

Mexico

On November 23, 2007, the use and trade of pseudoephedrine in Mexico was made illicit, as it was argued that it was extremely popular as a precursor in the synthesis of methamphetamine.[35]

Netherlands

Pseudoephedrine was withdrawn from sale in 1989 due to concerns about adverse cardiac side effects.[36]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, pseudoephedrine is currently classified as a Class B Part II controlled drug in the Misuse of Drugs Act 1975, making it illegal to supply or possess except on prescription.[37][38]

Pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, and any product containing these substances, e.g. cold and flu medicines, were first classified in October 2004 as Class C Part III (partially exempted) controlled drugs, due to being the principal ingredient in methamphetamine.[39] New Zealand Customs and police officers continued to make large interceptions of precursor substances believed to be destined for methamphetamine production. On 9 October 2009, Prime Minister John Key announced pseudoephedrine-based cold and flu tablets would become prescription-only drugs and reclassified as a class B2 drug.[40] The law was amended by The Misuse of Drugs Amendment Bill 2010, which passed in August 2011.[41]

Turkey

In Turkey, medications containing pseudoephedrine are available with prescription only.[42]

United Kingdom

In the UK, pseudoephedrine is available over the counter under the supervision of a qualified pharmacist, or on prescription. In 2007, the MHRA reacted to concerns over diversion of ephedrine and pseudoephedrine for the illicit manufacture of methamphetamine by introducing voluntary restrictions limiting over the counter sales to one box containing no more than 720 mg of pseudoephedrine in total per transaction. These restrictions became law in April 2008.[43] However no form of ID is required.

United States

Federal

The United States Congress has recognized that pseudoephedrine is used in the illegal manufacture of methamphetamine. In 2005, the Committee on Education and the Workforce heard testimony concerning education programs and state legislation designed to curb this illegal practice.

Attempts to control the sale of the drug date back to 1986, when federal officials at the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) first drafted legislation, later proposed by Senator Bob Dole, R-KS[clarification needed], that would have placed a number of chemicals used in the manufacture of illicit drugs under the Controlled Substances Act. The bill would have required each transaction involving pseudoephedrine to be reported to the government, and federal approval of all imports and exports. Fearing this would limit legitimate use of the drug, lobbyists from over the counter drug manufacturing associations sought to stop this legislation from moving forward, and were successful in exempting from the regulations all chemicals that had been turned into a legal final product, such as Sudafed.[44]

Prior to the passage of the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005, sales of the drug became increasingly regulated, as DEA regulators and pharmaceutical companies continued to fight for their respective positions. The DEA continued to make greater progress in their attempts to control pseudoephedrine as methamphetamine production skyrocketed, becoming a serious problem in the western United States. When purity dropped, so did the number of people in rehab and people admitted to emergency rooms with methamphetamine in their systems. However, this reduction in purity was usually short lived, as methamphetamine producers eventually found a way around the new regulations.[45]

Congress passed the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005 ("CMEA") as an amendment to the renewal of the USA Patriot Act.[46] Signed into law by president George W. Bush on March 6, 2006, the act amended 21 U.S.C. § 830, concerning the sale of pseudoephedrine-containing products. The law mandated two phases, the first needing to be implemented by April 8, 2006, and the second to be completed by September 30, 2006. The first phase dealt primarily with implementing the new buying restrictions based on amount, while the second phase encompassed the requirements of storage, employee training, and record keeping.[47] Though the law was mainly directed at pseudoephedrine products it also applies to all over-the-counter products containing ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine, their salts, optical isomers, and salts of optical isomers.[47] Pseudoephedrine was defined as a "scheduled listed chemical product" under 21 U.S.C. § 802(45(A)). The act included the following requirements for merchants ("regulated sellers") who sell such products:

- Required a retrievable record of all purchases, identifying the name and address of each party, to be kept for two years

- Required verification of proof of identity of all purchasers

- Required protection and disclosure methods in the collection of personal information

- Required reports to the Attorney General of any suspicious payments or disappearances of the regulated products

- Required training of employees with regard to the requirements of the CMEA. Retailers must self-certify as to training and compliance.

- The non-liquid dose form of regulated products may only be sold in unit dose blister packs

- Regulated products must be stored behind the counter or in a locked cabinet in such a way as to restrict public access

- Sales limits (per customer):

- Daily sales limit—must not exceed 3.6 grams of pseudoephedrine base without regard to the number of transactions

- 30-day (not monthly) sales limit—must not exceed 7.5 grams of pseudoephedrine base if sold by mail order or "mobile retail vendor"

- 30-day purchase limit—must not exceed 9 grams of pseudoephedrine base. (A misdemeanor possession offense under 21 U.S.C. § 844a for the person who buys it.)

In regards to the identification that may be used by an individual buying pseudoephedrine products the following constitute acceptable forms of identification:

- US passport

- Alien registration or permanent resident card

- Unexpired foreign passport with temporary I-551 stamp

- Unexpired Employment Authorization Document

- Driver's License or Government issued identification card (including Canadian driver's license)

- School ID with picture

- Voter's Registration card

- US Military Card

- Native American tribal documents[47]

The requirements were revised in the Methamphetamine Production Prevention Act of 2008 to require that a regulated seller of scheduled listed chemical products may not sell such a product unless the purchaser:[48]

- Presents a government issued photographic identification; and

- Signs the written logbook with his or her name, address, time and date of the sale, or signs in one of the following ways:

State

Most states also have laws regulating pseudoephedrine.[49][50][51]

The states of Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii (as of May 1, 2009[update]) Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana (as of August 15, 2009[update]), Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska,[52] Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia and Wisconsin have laws requiring pharmacies to sell pseudoephedrine "behind the counter". Though the drug can be purchased without a prescription, states can limit the number of units sold and can collect personal information from purchasers.[53]

The states of Oregon and Mississippi require a prescription for the purchase of products containing pseudoephedrine.[54][55] The state of Oregon reduced the number of methamphetamine lab seizures from 467 in 2004 (the final full year before implementation of the prescription only law)[56] to a new low of 12 in 2009.[57] However, the decrease in meth lab incidents in Oregon occurred largely before the prescription-only law took effect, according to a NAMSDL report titled Pseudoephedrine Prescription Laws in Oregon and Mississippi[53]. The report posits that the decline in meth lab incidents in both states may be due to other factors: "Mexican traffickers may have contributed to the decline in meth labs in Mississippi and Oregon (and surrounding states) as they were able to provide ample supply of equal or greater quality meth at competitive prices". Additionally, similar decreases in meth lab incidents were seen in surrounding states, according to the report, and meth-related deaths in Oregon have dramatically risen since 2007. Some municipalities in Missouri have enacted similar ordinances, including Washington,[58] Union,[59] New Haven,[60] Cape Girardeau[61] and Ozark.[62] Certain pharmacies in Terre Haute, Indiana do so as well.[63]

Another approach to controlling the drug on the state level which has been mandated by some state governments to control the purchases of their citizens is the use of electronic tracking systems, which require the electronic submission of specified purchaser information by all retailers who sell pseudoephedrine. 32 states now require the National Precursor Log Exchange (NPLEx) to be used for every pseudoephedrine and ephedrine OTC purchase, and ten of the eleven largest pharmacy chains in the US voluntarily contribute all of their similar transactions to NPLEx. These states have seen dramatic results in reducing the number of methamphetamine laboratory seizures. Prior to implementation of the system in Tennessee in 2005, methamphetamine laboratory seizures totaled 1,497 in 2004, but were reduced to 955 in 2005, and 589 in 2009.[57] Kentucky's program was implemented statewide in 2008, and since statewide implementation, the number of laboratory seizures has significantly decreased.[57] Oklahoma initially experienced success with their tracking system after implementation in 2006, as the number of seizures dropped in that year and again in 2007. However, in 2008, seizures began rising again, and have continued to rise in 2009.[57] However, when Oklahoma adopted NPLEx, their lab seizures also dropped significantly.

NPLEx appears to be successful by requiring the real-time submission of transactions, thereby enabling the relevant laws to be enforced at the point of sale. By creating a multi-state database and the ability to compare all transactions quickly, NPLEx enables pharmacies to deny purchases that would be illegal based on gram limits, age, or even to convicted meth offenders in some states. NPLEx also enforces the federal gram limits across state lines, which was impossible with state-operated systems. Access to the records is by law enforcement agencies only, through an online secure portal.[64]

Manufacture of amphetamines

Its membership in the amphetamine class has made pseudoephedrine a sought-after chemical precursor in the illicit manufacture of methamphetamine and methcathinone. As a result of the increasing regulatory restrictions on the sale and distribution of pseudoephedrine, many pharmaceutical firms have reformulated, or are in the process of reformulating medications to use alternative, but less effective,[27] decongestants, such as phenylephrine.

In the United States, federal laws control the sale of pseudoephedrine-containing products.[65][46][48] Many retailers in the US have created corporate policies restricting the sale of pseudoephedrine-containing products.[66][67] Their policies restrict sales by limiting purchase quantities and requiring a minimum age and government issued photographic identification.[46][48] These requirements are similar to and sometimes more stringent than existing law. Internationally, pseudoephedrine is listed as a Table I precursor under the United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances.[68]

Sports

Pseudoephedrine was on the IOC's banned substances list until 2004, when the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) list replaced the IOC list. Although WADA initially only monitored pseudoephedrine, it is once again on the banned list starting January 1, 2010.[69]

Pseudoephedrine is excreted through urine, and concentration in urine of this drug shows a large inter-individual spread; that is, the same dose can give a vast difference in urine concentration for different individuals.[70] Pseudoephedrine is approved to be taken up to 240 mg per day. In seven healthy male subjects this dose yielded a urine concentration range of 62.8 to 294.4 microgram per milliliter (µg/ml) with mean ± standard deviation 149 ± 72 µg/ml.[71] Thus, normal dosage of 240 mg pseudoephedrine per day can result in urine concentration levels exceeding the limit of 150 µg/ml set by WADA for about half of all users.[72] Furthermore, hydration status does not affect urinary concentration of pseudoephedrine.[73]

Canadian rower Silken Laumann was stripped of her 1995 Pan American Games team gold medal after testing positive for pseudoephedrine.[74]

In February 2000, Elena Berezhnaya and Anton Sikharulidze won gold at the 2000 European Figure Skating Championships but were stripped of their medals after Berezhnaya tested positive. This resulted in a three-month disqualification from the date of the test, and the medal being stripped.[75] She stated that she had taken cold medication approved by a doctor but had failed to inform the ISU as required.[76] The pair missed the World Championships that year as a result of the disqualification.

Romanian gymnast Andreea Răducan was stripped of her gold medal at the 2000 Summer Olympic Games after testing positive. She took two pills given to her by the team coach for a cold. Although she was stripped of the overall gold medal, she kept her other medals, and, unlike in most other doping cases, was not banned from competing again; only the team doctor was banned for a number of years. Ion Ţiriac, the president of the Romanian Olympic Committee, resigned over the scandal.[77][78]

In the 2010 Summer Olympic Gasmes, the IOC issued a reprimand against the Slovak ice hockey player Lubomir Visnovsky for usage of pseudoephedrine.[79]

In the 2014 Summer Olympic Gamess Team Sweden and Washington Capitals ice hockey player Nicklas Bäckström was prevented from playing in the final for usage of pseudoephedrine. Bäckström claimed he was using it as allergy medication.[80] In March 2014, the IOC Disciplinary Commission decided that Bäckström would be awarded the silver medal.[81] In January 2015 Bäckström, the IOC, WADA and the IIHF agreed to a settlement in which he accepted a reprimand but was cleared of attempting to enhance his performance.[82]

Detection of use

Pseudoephedrine may be quantified in blood, plasma, or urine to monitor any possible performance-enhancing use by athletes, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning, or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Many commercial immunoassay screening tests directed at the amphetamines cross-react appreciably with pseudoephedrine, but chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish pseudoephedrine from other phenethylamine derivatives. Blood or plasma pseudoephedrine concentrations are typically in the 50–300 µg/l range in persons taking the drug therapeutically, 500–3000 µg/l in people with substance use disorder involving pseudoephedrine, or poisoned patients and 10–70 mg/l in cases of acute fatal overdose.[83][84]

Popular culture

In the pilot episode of Breaking Bad, Walter White first synthesizes methamphetamine through the Nagai route, using red phosphorus and iodine to reduce pseudoephedrine.

In her critically acclaimed 2017 album Melodrama, pop artist Lorde references pseudoephedrine on the song "Writer in the Dark". The lyric reads: "I still feel you, now and then/Slow like pseudoephedrine/When you see me, will you say I've changed?"

Synthesis

Although pseudoephedrine occurs naturally as an alkaloid in certain plant species (for example, as a constituent of extracts from the Ephedra species, also known as ma huang, in which it occurs together with other isomers of ephedrine), the majority of pseudoephedrine produced for commercial use is derived from yeast fermentation of dextrose in the presence of benzaldehyde. In this process, specialized strains of yeast (typically a variety of Candida utilis or Saccharomyces cerevisiae) are added to large vats containing water, dextrose and the enzyme pyruvate decarboxylase (such as found in beets and other plants). After the yeast has begun fermenting the dextrose, the benzaldehyde is added to the vats, and in this environment the yeast converts the ingredients to the precursor l-phenylacetylcarbinol (L-PAC). L-PAC is then chemically converted to pseudoephedrine via reductive amination.[85]

The bulk of pseudoephedrine is produced by commercial pharmaceutical manufacturers in India and China, where economic and industrial conditions favor its mass production for export.[86]

See also

- Amphetamine

- Carbinoxamine/pseudoephedrine

- Ephedrine

- Methamphetamine

- N-Methylpseudoephedrine

- Phenylephrine

- Phenylpropanolamine

- Thomas Latham, sponsor of the "Angie Fatino Save the Children from Meth Act"

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 "Pseudoephedrine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 BNF 79. London: Pharmaceutical Press. March 2020. p. 1239. ISBN 978-0857113658.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Laurence L Brunton, ed. (2006). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. ISBN 0-07-142280-3.

- ↑ Ladenburg, A.; Oelschlägel, C. (1889). "Ueber das "Pseudo-Ephedrin"" [On pseudo-ephedrine]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 22 (2): 1823–1827. doi:10.1002/cber.18890220225. Archived from the original on 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Farmer, Steven (2017). Strange Chemistry: The Stories Your Chemistry Teacher Wouldn't Tell You. John Wiley & Sons. p. 294. ISBN 978-1-119-26529-0. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Trinh, KV; Kim, J; Ritsma, A (15 November 2015). "Effect of Pseudoephedrine in Sport: a Systemic Review". BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine. 1 (1): e000066. doi:10.1136/bmjsem-2015-000066. PMC 5117033. PMID 27900142.

- ↑ "American Urological Association - Medical Student Curriculum - Urinary Incontinence". American Urological Association. Archived from the original on 2015-07-09. Retrieved 2015-08-12.

- ↑ "Acute urinary retention due to pseudoephedrine hydrochloride in a 3-year-old child". The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics. Archived from the original on 2016-08-14. Retrieved 2015-08-12.

- ↑ Kiyoshi Minamizawa (2006). "Effect of d-Pseudoephedrine on Cough Reflex and Its Mode of Action in Guinea Pigs". Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 102 (1): 136–142. doi:10.1254/jphs.FP0060526. PMID 16974066.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)[permanent dead link] - ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bicopoulos D, editor. AusDI: Drug information for the healthcare professional, 2nd edition. Castle Hill: Pharmaceutical Care Information Services; 2002.

- ↑ Weiss, Barry D. (2005-01-15). "Selecting Medications for the Treatment of Urinary Incontinence – January 15, 2005 – American Family Physician". American Family Physician. Aafp.org. 71 (2): 315–322. Archived from the original on 2020-09-28. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006. ISBN 0-9757919-2-3

- ↑ Vidal C, Prieto A, Pérez-Carral C, Armisén M (April 1998). "Nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption due to pseudoephedrine". Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 80 (4): 309–10. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62974-2. PMID 9564979.

- ↑ "Adco-Tussend". Home.intekom.com. 1993-03-15. Archived from the original on 2012-04-30. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ Cantu C, Arauz A, Murillo-Bonilla LM, López M, Barinagarrementeria F (July 2003). "Stroke associated with sympathomimetics contained in over-the-counter cough and cold drugs". Stroke. 34 (7): 1667–72. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000075293.45936.FA. PMID 12791938.

- ↑ Deckx, Laura; De Sutter, An Im; Guo, Linda; Mir, Nabiel A.; van Driel, Mieke L. (17 October 2016). "Nasal decongestants in monotherapy for the common cold" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD009612. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009612.pub2. PMC 6461189. PMID 27748955. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 American Medical Association, AMA Department of Drugs (1977). AMA Drug Evaluations. PSG Publishing Co., Inc. p. 627.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Thomson/Micromedex (2007). Drug Information for the Health Care Professional, Volume 1. Greenwood Village, CO. p. 2452.

- ↑ Drew, CD; Knight, GT; Hughes, DT; Bush, M (1978). "Comparison of the effects of D-(−)-ephedrine and L-(+)-pseudoephedrine on the cardiovascular and respiratory systems in man". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 6 (3): 221–225. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1978.tb04588.x. PMC 1429447. PMID 687500.

- ↑ Popat N. Patil, A. Tye and J.B. LaPidus (1965). "A pharmacological study of the ephedrine isomers". JPET. 148 (2): 158–168. PMID 14301006. Archived from the original on 2020-01-07. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ↑ Martindale (1989). Reynolds JEF (ed.). Martindale: The complete drug reference (29th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 0-85369-210-6.

- ↑ Proposed International Non-Proprietary Names (Prop. I.N.N.): List 11 Archived 2012-10-19 at the Wayback Machine WHO Chronicle, Vol. 15, No. 8, August 1961, pp. 314–20

- ↑ "Pseudoephedrine Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ↑ "Drug Pamphlet: Congestal". 2017-02-12. Archived from the original on 2018-12-13. Retrieved 2018-12-13.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2018-12-13. Retrieved 2018-12-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Project STOP video – Online Advertising". Innovationrx.com.au. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Hatton RC, Winterstein AG, McKelvey RP, Shuster J, Hendeles L (2007). "Efficacy and safety of oral phenylephrine: systematic review and meta-analysis". Ann Pharmacother. 41 (3): 381–90. doi:10.1345/aph.1H679. PMID 17264159.

- ↑ Horak, F; Zieglmayer, P; Zieglmayer, R; Lemell, P; Yao, R; Staudinger, H; Danzig, M (2009). "A placebo-controlled study of the nasal decongestant effect of phenylephrine and pseudoephedrine in the Vienna Challenge Chamber". Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 102 (2): 116–20. doi:10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60240-2. PMID 19230461.

- ↑ Eccles, R (2007). "Substitution of phenylephrine for pseudoephedrine as a nasal decongeststant. An illogical way to control methamphetamine abuse". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 63 (1): 10–4. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02833.x. PMC 2000711. PMID 17116124.

- ↑ "Archived - Health Canada Reminds Canadians not to use Ephedra/Ephedrine Products". healthycanadians.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2014-04-27. Retrieved 2015-07-01.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-10-25. Retrieved 2015-08-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Family Health Online - Family Health Magazine -PHARMACY CARE - Over-the-Counter Medication - Why must I ask for that?". Archived from the original on 2016-06-18. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ "Gobierno prohĂbe antigripales con pseudoefedrina a partir de finales de 2010 – Archivo – Archivo Digital de Noticias de Colombia y el Mundo desde 1.990" [Government Prohibits Flu Pseudoephedrine in Late 2010 - Archive - News Archive Digital Colombia and the World since 1990] (in Spanish). Eltiempo.com. 8 July 2009 [Published 11 August 2009]. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "Customs Information". Consulate-General of Japan in Seattle. Archived from the original on August 19, 2015. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Prohibirán definitivamente uso de pseudoefedrina" [A Permanent Ban on Pseudoephedrine] (in Spanish). 23 November 2007 [Published 2 December 2007]. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Katrina Megget (2 Sep 2007). "Pseudoephedrine drugs still OTC". Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ↑ "Controlled drugs". www.health.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 8 July 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Misuse of Drugs Act 1975 No 116, Public Act 8 Exemptions from sections 6 and 7". www.legislation.govt.nz. 22 December 2016. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Ephedrine and Pseudoephedrine to Become Controlled Drugs". Medsafe, New Zealand Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Authority. Archived from the original on 2007-03-08.

- ↑ "Chemical Brothers". Listener (New Zealand). Archived from the original on 2010-05-23.

- ↑ "Misuse of Drugs Amendment Bill". parliament.nz. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ "Kontrole Tabi İlaçlar" (PDF). Social Security Institution of Republic of Turkey. July 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-11. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ↑ "Drug Safety Update, March 2008". The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency and the Commission on Human Medicines. 2008-06-30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-14.

- ↑ "Search OregonLive.com". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on 2016-08-17. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ↑ "How Legislation Changed Meth Purity" (PDF). The Oregonian. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-11-15. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 "CMEA (The Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005)". DEA Diversion Control Division. 14 July 2017. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 "DEA Interim Final Regulation: Ephedrine, Pseudoephedrine, and Phenylpropanolamine Requirements" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-10-18.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 "2011 - Final Rule: Implementation of the Methamphetamine Production Prevention Act of 2008". DEA Diversion Control Division. 1 November 2011. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "State Ephedrine and Pseudoephedrine Single Over-The-Counter Transaction Limits". www.namsdl.org. National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws (NAMSDL). 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ↑ "State Daily Gram Limits for Over-The-Counter Transactions Involving Ephedrine and Pseudoephedrine". www.namsdl.org. National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws (NAMSDL). 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 14, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ↑ "State 30 Day Gram Limits for Over-The-Counter Transactions Involving Ephedrine and Pseudoephedrine". www.namsdl.org. National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws (NAMSDL). 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 15, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Nebraskans to sign for Sudafed". Lincoln Journal-Star. 13 Mar 2006. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 20 Aug 2012.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "The National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws (NAMSDL) - Issues and Events". www.namsdl.org. Archived from the original on 2015-10-03. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ↑ "MS Senate passes bill to restrict pseudoephedrine sales". Associated Content. WLOX. February 2, 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ↑ Bovett, Rob (November 15, 2010). "How to Kill the Meth Monster". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved November 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-03-09. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 "DEA, Maps of Methamphetamine Lab Incidents". Justice.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-09-10. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ "Council Passes Law Restricting Pseudoephedrine". The Washington Missourian. July 7, 2009. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Union Board Approves Pseudoephedrine Ordinance". The Washington Missourian. October 13, 2009. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ "New Haven Passes Prescription Law". The Washington Missourian. November 11, 2010. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Cape Girardeau City Council passes prescription requirement for pseudoephedrine". The Southeast Missourian. December 7, 2010. Archived from the original on January 28, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Ozark passes pseudoephedrine ban: Drug now prescription-only". CCHeadliner.com. June 18, 2013. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ↑ Trigg, Lisa (May 20, 2010). "Four Valley pharmacies to require prescriptions for certain products to help fight meth problem". Terre Haute Tribune-Star. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2010. (Subscription required, free access for first 30 days)

- ↑ "NPLEx - National Precursor Log Exchange". www.nplexservice.com. Archived from the original on 2015-10-12. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ↑ "Legal Requirements for the Sale and Purchase of Drug Products". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 November 2017. Archived from the original on 17 February 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Pseudoephedrine Compliance". Walgreens. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ↑ "Target Announces That All Products Containing Pseudoephedrine Will Be Placed Behind Pharmacy Counter". PRNewswire. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - RedListE2007.doc" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-02-27. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ "WADA 2010 Prohibited List Now Published – World Anti-Doping Agency". Wada-ama.org. Archived from the original on 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ "Elimination of ephedrines in urine following multiple dosing the consequences for athletes in relation to doping control". Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ Strano-Rossi, S.; Leone, D.; Torre, X. D. L.; Botrè, F. (2009). "The Relevance of the Urinary Concentration of Ephedrines in Anti-Doping Analysis: Determination of Pseudoephedrine, Cathine, and Ephedrine After Administration of Over-the-Counter Medicaments". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 31 (4): 520–6. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181ac6006. PMID 19571776.

- ↑ "Ressources" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-29. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ↑ Jolley, Daniel; Science, School of Sport; Exercise; Health, and; Australia, University of Western; Crawley; Australia., Western; Dawson, Brian; Maloney, Shane K. (2014). "Hydration and Urinary Pseudoephedrine Levels After a Simulated Team Game". International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism. 24 (3): 325–332. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.2013-0076. PMID 24458099. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-10.

- ↑ "Silken tests positive". Archived from the original on 2014-03-04. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ Wallechinsky, David (2009). Complete Book of the Winter Olympics. ISBN 9781553655022. Archived from the original on 16 September 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ↑ "2000 World Championships – Pairs". Ice Skating International. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ↑ "Summer Olympics 2000 Raducan tests positive for stimulant". Assets.espn.go.com. 2000-09-26. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ "Amanar Tops Romanian Money List". International Gymnast Magazine Online. 15 October 2000. Archived from the original on 2001-07-15. Retrieved 2012-05-06.

- ↑ "IOC issues a reprimand against Slovakian ice hockey player". Archived from the original on 2014-03-08. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ "Sweden's Bäckström tests positive for banned substance". Archived from the original on 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2014-02-24.

- ↑ "IOC Decision - Swedish ice hockey player Nicklas Backstrom to receive Sochi silver medal". IOC. 14 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ Prewitt, Alex (15 January 2015). "Nicklas Backstrom's Olympic doping appeal resolved with reprimand". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 17 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ↑ Boland DM, Rein J, Lew EO, Hearn WL (2003). "Fatal cold medication intoxication in an infant". J Anal Toxicol. 27 (7): 523–6. doi:10.1093/jat/27.7.523. PMID 14607011.

- ↑ R. Baselt (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1344–1346. Archived from the original on 2020-12-04. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ↑ Oliver AL, Anderson BN, Roddick FA (1999). "Factors affecting the production of L-phenylacetylcarbinol by yeast: a case study". Adv. Microb. Physiol. Advances in Microbial Physiology. 41: 1–45. doi:10.1016/S0065-2911(08)60164-2. ISBN 978-0-12-027741-4. PMID 10500843.

- ↑ Suo, Steve. Clamp down on shipments of raw ingredients. The Oregonian; 6 October 2004. From a version reprinted on a U.S. congressional caucus Archived 2006-05-09 at the Wayback Machine website.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- CS1 errors: empty unknown parameters

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from July 2018

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with permanently dead external links

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- Wikipedia articles incorporating the PD-notice template

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chem-molar-mass both hardcoded and calculated

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drug has EMA link

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2011

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2006

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Wikipedia articles needing clarification from February 2020

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from May 2009

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from August 2009

- Amphetamine alkaloids

- Decongestants

- Methamphetamine

- Norepinephrine releasing agents

- Phenylethanolamines

- RTT