Famotidine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /fəˈmɒtɪdiːn/ |

| Trade names | Pepcid, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth (tablets), Intravenous |

| Defined daily dose | 40 mg[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a687011 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 40–45% (by mouth)[2] |

| Protein binding | 15–20%[2] |

| Metabolism | hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 2.5–3.5 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Kidney (25–30% unchanged [Oral])[2] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

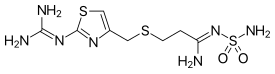

| Formula | C8H15N7O2S3 |

| Molar mass | 337.44 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Famotidine, sold under the brand name Pepcid among others, is a medication that decreases stomach acid production.[3] It is used to treat peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.[3] It is taken by mouth or by injection into a vein.[3] It begins working within an hour.[3]

Common side effects include headache, intestinal upset, and dizziness.[3] Serious side effects may include pneumonia and seizures.[3][4] Use in pregnancy appears safe but has not been well studied while use during breastfeeding is not recommended.[5] It is a histamine H2 receptor antagonist.[3]

Famotidine was patented in 1979 and came into medical use in 1985.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[4] A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £30 as of 2019.[4] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about $2.[7] In 2017, it was the 115th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than six million prescriptions.[8][9]

Medical uses

- Relief of heartburn, acid indigestion, and sour stomach

- Treatment for gastric and duodenal ulcers

- Treatment for pathologic gastrointestinal hypersecretory conditions such as Zollinger–Ellison syndrome and multiple endocrine adenomas

- Treatment for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Treatment for esophagitis

- Part of a multidrug regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication, although omeprazole may be somewhat more effective.[10][11][12][13][14][15]

- Prevention of NSAID-induced peptic ulcers.[16][17]

- Given to surgery patients before operations to reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonitis.[18][19][20]

Famotidine is also given to dogs and cats with acid reflux.[21] Famotidine has been used in combination with an H1 antagonist to treat and prevent urticaria caused by an acute allergic reaction.[22]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 40 mg by mouth or by injection.[1] For adults for GERD 20 mg twice per day by mouth for six weeks may be used.[3] For esophagitis doses of up to 40 mg twice per day for 3 months may be used.[3]

Side effects

The most common side effects associated with famotidine use include headache, dizziness, and constipation or diarrhea.[23][24]

Famotidine may contribute to QT prolongation,[25] particularly when used with other QT-elongating drugs, or in people with poor kidney function.[26]

Mechanism of action

Activation of H2 receptors located on parietal cells stimulates the proton pump to secrete acid. Famotidine (H2 antagonist) blocks the action of histamine in the parietal cells, ultimately blocking acid secretion in the stomach.

Interactions

Unlike cimetidine, the first H2 antagonist, famotidine has no effect on the cytochrome P450 enzyme system, and does not appear to interact with other drugs.[27]

History

Famotidine was developed by Yamanouchi Pharmaceutical Co.[28] It was licensed in the mid-1980s by Merck & Co.[29] and is marketed by a joint venture between Merck and Johnson & Johnson. The imidazole ring of cimetidine was replaced with a 2-guanidinothiazole ring. Famotidine proved to be nine times more potent than ranitidine, and thirty-two times more potent than cimetidine.[30]

It was first marketed in 1981. Pepcid RPD orally disintegrating tablets were released in 1999. Generic preparations became available in 2001, e.g. Fluxid (Schwarz) or Quamatel (Gedeon Richter Ltd.).

In the United States and Canada, a product called Pepcid Complete, which combines famotidine with an antacid in a chewable tablet to quickly relieve the symptoms of excess stomach acid, is available. In the UK, this product was known as Pepcidtwo prior to its discontinuation in April 2015.[31]

Famotidine has poor bioavailibility (50%) due to low gastroretention time. Famotidine is less soluble at higher pH, and when used in combination with antacids gastroretention time is increased. This promotes local delivery of these drugs to receptors in the parietal cell wall and increases bioavailibility. Researchers are developing tablet formulations that rely on other gastroretentive drug delivery systems such as floating tablets to further increase bioavailibility.[32]

Preparations

It is taken by mouth, as a tablet or suspension, or by injection into a vein.[3]

Certain preparations of famotidine are available over the counter (OTC) in various countries. In the United States and Canada, 10 mg and 20 mg tablets, sometimes in combination with an antacid,[33][34] are available OTC. Larger doses still require a medical prescription.

Formulations of famotidine in combination with ibuprofen were marketed by Horizon Pharma under the trade name Duexis.[35]

Society and culture

Cost

A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £30 as of 2019.[4] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about $2.[7] In 2017, it was the 115th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than six million prescriptions.[8][9]

-

Famotidine costs (US)

-

Famotidine prescriptions (US)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Truven Health Analytics, Inc. DRUGDEX® System (Internet) [cited 2013 Oct 10]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomsen Healthcare; 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 "Famotidine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 74–75. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ "Famotidine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 9 February 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 444. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2020-07-29. Retrieved 2020-05-07.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Famotidine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ Kanayama S (January 1999). "[Proton-pump inhibitors versus H2-receptor antagonists in triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication]". Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine. 57 (1): 153–6. PMID 10036954.

- ↑ Soga T, Matsuura M, Kodama Y, Fujita T, Sekimoto I, Nishimura K, et al. (August 1999). "Is a proton pump inhibitor necessary for the treatment of lower-grade reflux esophagitis?". Journal of Gastroenterology. 34 (4): 435–40. doi:10.1007/s005350050292. PMID 10452673.

- ↑ Borody TJ, Andrews P, Fracchia G, Brandl S, Shortis NP, Bae H (October 1995). "Omeprazole enhances efficacy of triple therapy in eradicating Helicobacter pylori". Gut. 37 (4): 477–81. doi:10.1136/gut.37.4.477. PMC 1382896. PMID 7489931.

- ↑ Hu FL, Jia JC, Li YL, Yang GB (2003). "Comparison of H2-receptor antagonist- and proton-pump inhibitor-based triple regimens for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori in Chinese patients with gastritis or peptic ulcer". The Journal of International Medical Research. 31 (6): 469–74. doi:10.1177/147323000303100601. PMID 14708410.

- ↑ Kirika NV, Bodrug NI, Butorov IV, Butorov SI (2004). "[Efficacy of different schemes of anti-helicobacter therapy in duodenal ulcer]". Terapevticheskii Arkhiv. 76 (2): 18–22. PMID 15106408.

- ↑ Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Nebiki H, Chono S, Uno H, Kitada K, et al. (June 2005). "Famotidine vs. omeprazole: a prospective randomized multicentre trial to determine efficacy in non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 21 (Suppl 2): 10–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02468.x. PMID 15943841.

- ↑ La Corte R, Caselli M, Castellino G, Bajocchi G, Trotta F (June 1999). "Prophylaxis and treatment of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal disorders". Drug Safety. 20 (6): 527–43. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920060-00006. PMID 10392669.

- ↑ Laine L, Kivitz AJ, Bello AE, Grahn AY, Schiff MH, Taha AS (March 2012). "Double-blind randomized trials of single-tablet ibuprofen/high-dose famotidine vs. ibuprofen alone for reduction of gastric and duodenal ulcers". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 107 (3): 379–86. doi:10.1038/ajg.2011.443. PMC 3321505. PMID 22186979.

- ↑ Escolano F, Castaño J, López R, Bisbe E, Alcón A (October 1992). "Effects of omeprazole, ranitidine, famotidine and placebo on gastric secretion in patients undergoing elective surgery". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 69 (4): 404–6. doi:10.1093/bja/69.4.404. PMID 1419452.

- ↑ Vila P, Vallès J, Canet J, Melero A, Vidal F (November 1991). "Acid aspiration prophylaxis in morbidly obese patients: famotidine vs. ranitidine". Anaesthesia. 46 (11): 967–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1991.tb09860.x. PMID 1750602.

- ↑ Jahr JS, Burckart G, Smith SS, Shapiro J, Cook DR (July 1991). "Effects of famotidine on gastric pH and residual volume in pediatric surgery". Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 35 (5): 457–60. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.1991.tb03328.x. PMID 1887750.

- ↑ "Famotidine". PetMD. Archived from the original on 2015-05-19. Retrieved 2015-06-07.

- ↑ Fogg TB, Semple D (29 November 2007). "Combination therapy with H2 and H1 antihistamines in acute, non compromising allergic reactions". BestBets. Manchester, England: Manchester Royal Infirmary. Archived from the original on 16 May 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ↑ "Common Side Effects of Pepcid (Famotidine) Drug Center". RxList. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- ↑ "Drugs & Medications". www.webmd.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- ↑ Fazio G, Vernuccio F, Grutta G, Re GL (26 April 2013). "Drugs to be avoided in patients with long QT syndrome: Focus on the anaesthesiological management". World Journal of Cardiology. 5 (4): 87–93. doi:10.4330/wjc.v5.i4.87. PMC 3653016. PMID 23675554.

- ↑ Lee KW, Kayser SR, Hongo RH, Tseng ZH, Scheinman MM (May 2004). "Famotidine and long QT syndrome". The American Journal of Cardiology. 93 (10): 1325–1327. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.025. PMID 15135720.

- ↑ Humphries TJ, Merritt GJ (August 1999). "Review article: drug interactions with agents used to treat acid-related diseases". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 13 (Suppl 3): 18–26. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00021.x. PMID 10491725.

- ↑ US patent 4283408, Yasufumi Hirata, Isao Yanagisawa, Yoshio Ishii, Shinichi Tsukamoto, Noriki Ito, Yasuo Isomura and Masaaki Takeda, "Guanidinothiazole compounds, process for preparation and gastric inhibiting compositions containing them", issued 11 August 1981

- ↑ "Sankyo Pharma". Skyscape Mediwire. 2002. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ↑ Howard JM, Chremos AN, Collen MJ, McArthur KE, Cherner JA, Maton PN, et al. (April 1985). "Famotidine, a new, potent, long-acting histamine H2-receptor antagonist: comparison with cimetidine and ranitidine in the treatment of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome". Gastroenterology. 88 (4): 1026–33. doi:10.1016/s0016-5085(85)80024-x. PMID 2857672.

- ↑ "PepcidTwo Chewable Tablet". Archived from the original on 18 July 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ↑ "Formulation and Evaluation of Gastroretentive Floating Tablets of Famotidine". Farmavita.Net. 2008. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ↑ Pepcid Complete

- ↑ "Famotidine". Medline Plus. Archived from the original on 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

- ↑ "Duexis". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-18. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- RTT

- Amidines

- Guanidines

- H2 receptor antagonists

- Sulfamides

- Thiazoles

- Thioethers