Atenolol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tenormin, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Selective β1 receptor antagonist |

| Main uses | High blood pressure, heart-associated chest pain, prevention of migraines[1][2] |

| Side effects | Feeling tired, heart failure, dizziness, depression, shortness of breath[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, IV |

| Defined daily dose | 75 mg[3] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684031 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 40–50% |

| Protein binding | 6–16% |

| Metabolism | Liver <10% |

| Elimination half-life | 6 hours[4] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H22N2O3 |

| Molar mass | 266.341 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

Atenolol is a beta blocker medication primarily used to treat high blood pressure and heart-associated chest pain.[1] Atenolol, however, does not seem to improve mortality in those with high blood pressure.[5][6] Other uses include the prevention of migraines and treatment of certain irregular heart beats.[1][2] It is taken by mouth or by injection into a vein.[1][2] It can also be used with other blood pressure medications.[2]

Common side effects include feeling tired, heart failure, dizziness, depression, and shortness of breath.[1] Other serious side effects include bronchospasm.[1] Use is not recommended during pregnancy[1] and other medications are preferred when breastfeeding.[7] It works by blocking β1-adrenergic receptors in the heart, thus decreasing the heart rate and workload.[1]

Atenolol was patented in 1969 and approved for medical use in 1975.[8] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines as an alternative to bisoprolol.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[1] The defined daily dose is 75 mg by mouth.[3] In the United States, at this dose, the wholesale cost per month is more than US$25 as of 2021.[10][11] In the United Kingdom, a month of treatment costs the NHS less than £1.50 as of 2020.[2] In 2018, it was the 42nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with nearly 19 million prescriptions.[12][13]

Medical uses

Atenolol is used for a number of conditions including hypertension, angina, long QT syndrome, acute myocardial infarction, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, and the symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.[14]

Although atenolol reduces blood pressure, how effective it is at reducing cardiovascular risk has been debated.[15] The role for β-blockers in general in hypertension was downgraded in June 2006 in the United Kingdom, and later in the United States, as they are less appropriate than other agents such as ACE inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, thiazide diuretics and angiotensin receptor blockers, particularly in the elderly.[16][17][18] Antihypertensive therapy with atenolol provides weaker protective action against cardiovascular complications (e.g. myocardial infarction and stroke) compared to the newer more selective β-blockers.[19] In some cases, diuretics are superior.[20]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 75 mg by mouth or by injection.[3]

Side effects

Common side effects include feeling tired, heart failure, dizziness, depression, and shortness of breath.[1] Other serious side effects include bronchospasm.[1] Use is not recommended during pregnancy.[1] Other medications are preferred when breastfeeding, as compared to other β-blockers, atenolol appears in breast milk in greater amounts and is associated with restricted fetal growth.[2][21]

Overdose

Symptoms of overdose are due to excessive pharmacodynamic actions on β1 and also β2-receptors. These include bradycardia (slow heartbeat), severe hypotension with shock, acute heart failure, hypoglycemia and bronchospastic reactions. Treatment is largely symptomatic. Hospitalization and intensive monitoring is indicated. Activated charcoal is useful to absorb the drug. Atropine will counteract bradycardia, glucagon helps with hypoglycemia, dobutamine can be given against hypotension and the inhalation of a β2-mimetic as hexoprenalin or salbutamol will terminate bronchospasms. Blood or plasma atenolol concentrations may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Plasma levels are usually less than 3 mg/L during therapeutic administration, but can range from 3–30 mg/L in overdose victims.[22][23]

Society and culture

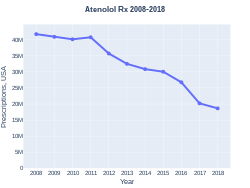

Atenolol has been given as an example of how slow healthcare providers are to change their prescribing practices in the face of medical evidence that indicates that a drug is ineffective.[24] In 2012, 33.8 million prescriptions were written to American patients for this drug.[24] In 2014, it was in the top (most common) 1% of drugs prescribed to Medicare patients.[24] Although the number of prescriptions has been declining steadily since the evidence against its efficacy was published, it has been estimated that it would take 20 years for doctors to stop prescribing it for hypertension.[24] The BNF has advised due care in writing the prescription as atenolol has been confused with amlodipine.[2]

Cost

In 2021, atenolol is the 42nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with almost 19 million prescriptions.[12][13] In the United States, the wholesale cost per month of 75mg atenolol daily is more than US$25 as of 2021.[10] In the United Kingdom, a month of treatment at this dose costs the NHS about £1.50 as of 2020.[2]

-

Atenolol costs (USA)

-

Atenolol prescriptions (USA)

Formulations

Atenolol tablets come in doses of 25mg, 50mg and 100mg.[2] The Tenormin brand is atenolol alone.[1][2] Atenolol combined with the diuretic chlorthalidone is available in the United States as brands Tenoretic, Tenoretic 50 and Tenoretic 100.[1] In the UK, 50 mg of atenolol combined with 20mg of nifedipine is available in a modified release form, Tenif.[2] An oral suspension of 500micrograms of atenolol per 1ml (Tenormin), and oral solution of 5mg atenolol per 1ml, maybe available on special order.[2]

-

Atenolol varieties

-

Tenoretic (atenolol combined with chlorthalidone

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 "Atenolol Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 12 October 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ Benowitz, Neal L. (2020). "11. Antihypertensive agents". In Katzung, Bertram G.; Trevor, Anthony J. (eds.). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-260-45231-0. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ↑ Tomiyama H, Yamashina A (2014). "Beta-Blockers in the Management of Hypertension and/or Chronic Kidney Disease". International Journal of Hypertension. 2014: 919256. doi:10.1155/2014/919256. PMC 3941231. PMID 24672712.

- ↑ DiNicolantonio JJ, Fares H, Niazi AK, Chatterjee S, D'Ascenzo F, Cerrato E, Biondi-Zoccai G, Lavie CJ, Bell DS, O'Keefe JH (2015). "β-Blockers in hypertension, diabetes, heart failure and acute myocardial infarction: a review of the literature". Open Heart. 2 (1): e000230. doi:10.1136/openhrt-2014-000230. PMC 4371808. PMID 25821584.

- ↑ "Atenolol use while Breastfeeding". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ↑ Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 461. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Atenolol Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ↑ "NADAC as of 2018-12-19". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. 2021. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Atenolol - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ "Atenolol". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ↑ Levene, Steven; Donnelly, Richard (2011). "4. Reducing cardiovascular risk". Management of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus E-Book: A Practical Guide. Elsevier. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-08-0449838. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ↑ Wiysonge, CS; Bradley, HA; Volmink, J; Mayosi, BM; Opie, LH (January 2017). "Beta-blockers for hypertension". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1: CD002003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub5. PMC 5369873. PMID 28107561.

- ↑ Sheetal Ladva (28 June 2006). "NICE and BHS launch updated hypertension guideline". National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ↑ Cruickshank, JM (August 2007). "Are we misunderstanding beta-blockers". International Journal of Cardiology. 120 (1): 10–27. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.01.069. PMID 17433471.

- ↑ Dézsi, Csaba András; Szentes, Veronika (2017). "The Real Role of β-Blockers in Daily Cardiovascular Therapy". American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs. 17 (5): 361–373. doi:10.1007/s40256-017-0221-8. ISSN 1175-3277. PMID 28357786. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ↑ Carlberg B, Samuelsson O, Lindholm LH (2004). "Atenolol in hypertension: is it a wise choice?". The Lancet. 364 (9446): 1684–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17355-8. PMID 15530629.

- ↑ Florio, Karen L.; DeZorzi, Christopher; Williams, Emily; Swearingen, Kathleen; Magalski, Anthony (31 October 2020). "Cardiovascular Medications in Pregnancy: A Primer". Cardiology Clinics. 39 (1): 33–54. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2020.09.011. ISSN 0733-8651. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ↑ DeLima LG, Kharasch ED, Butler S (1995). "Successful pharmacologic treatment of massive atenolol overdose: sequential hemodynamics and plasma atenolol concentrations". Anesthesiology. 83 (1): 204–207. doi:10.1097/00000542-199507000-00025. PMID 7605000.

- ↑ R. Baselt (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, Calif.: Biomedical Publications. pp. 116–117.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Epstein, David; ProPublica (22 July 2017). "When Evidence Says No, But Doctors Say Yes". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: date format

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Acetamides

- AstraZeneca brands

- Beta blockers

- Peripherally selective drugs

- 1976 in science

- Products introduced in 1976

- N-isopropyl-phenoxypropanolamines

- RTT

- World Health Organization essential medicines (alternatives)