Prasterone

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Astenile, Cetovister, 17-Chetovis, others[1] |

| Other names | EL-10; GL-701; KYH-3102; Androst-5-en-3β-ol-17-one; 3β-Hydroxyandrost-5-en-17-one; 5,6-Didehydroepiandrosterone;[2] Dehydroisoepiandrosterone[1] |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Androgen; Anabolic steroid; Estrogen; Neurosteroid |

| Main uses | Postmenopausal vaginal atrophy[3] |

| Side effects | Vaginal discharge, abnormal Pap smear, weight change, acne, oily skin, increased hair growth[4][5][6] |

| Routes of use | By mouth, vaginal (insert), intramuscular injection (as prasterone enanthate), injection (as prasterone sodium sulfate) |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 50%[7] |

| Metabolism | Liver[7] |

| Metabolites | • Androsterone[7] • Etiocholanolone[7] • @@@2@@@ sulfate[7] • Androstenedione[7] • Androstenediol[7] • Testosterone[7] • Dihydrotestosterone • Androstanediol[7] • Estrone • Estradiol |

| Elimination half-life | DHEA: 25 minutes[8] DHEA-S: 11 hours[8] |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H28O2 |

| Molar mass | 288.431 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 148.5 °C (299.3 °F) |

| |

| |

Prasterone, also known as dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and sold under the brand names Intrarosa among others, is a medication and dietary supplement.[3][5] As a medication it is used to treat postmenopausal women with vaginal atrophy.[3] For this purpose it is used in the vagina.[3] As a supplements it is sold with claims of anti-aging properties.[5]

Common side effects include vaginal discharge and abnormal Pap smear.[6] Other side effects may include weight change, acne, oily skin, and increased hair growth.[4][5] It is a naturally occurring steroid hormone which is converted into androgens and estrogens.[9]

Prasterone was discovered in 1934.[5] An association between DHEA levels and aging was reported in 1965.[7] The compound started being used for health claims in the 1980s.[7] It was approved for medical use in Europe in 2018.[3] In the United Kingdom 4 weeks of treatment costs the NHS about £16 in 2021 while in the United States this amount costs about 210 USD.[4][6] The marketing of over-the-counter supplements is allowed in the United States.[7]

Medical uses

Vaginal atrophy

Prasterone is approved in a vaginal insert formulation for the treatment of atrophic vaginitis.[10][11] The mechanism of action of prasterone for this indication is unknown, though it may involve local metabolism of prasterone into androgens and estrogens.[11]

It is used at a dose of 6.5 mg, once per day, in the form of a pessary.[3]

Deficiency

DHEA and DHEA sulfate are produced by the adrenal glands. In people with adrenal insufficiency such as in Addison's disease, there may be deficiency of DHEA and DHEA sulfate. In addition, levels of these steroids decrease throughout life and are 70 to 80% lower in the elderly relative to levels in young adults. Prasterone can be used to increase DHEA and DHEA sulfate levels in adrenal insufficiency and older age. Although there is deficiency of these steroids in such individuals, clinical benefits if any, are uncertain, and there is insufficient evidence support the use of prasterone for such purposes.[12][13]

Menopause

Prasterone is sometimes used as an androgen in menopausal hormone therapy.[14] In addition to prasterone itself, a long-lasting ester prodrug of prasterone, prasterone enanthate, is used in combination with estradiol valerate for the treatment of menopausal symptoms under the brand name Gynodian Depot.[15][16][17][18][19][20]

| Route | Medication | Major brand names | Form | Dosage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | Testosterone undecanoate | Andriol, Jatenzo | Capsule | 40–80 mg 1x/1–2 days |

| Methyltestosterone | Metandren, Estratest | Tablet | 0.5–10 mg/day | |

| Fluoxymesterone | Halotestin | Tablet | 1–2.5 mg 1x/1–2 days | |

| Normethandronea | Ginecoside | Tablet | 5 mg/day | |

| Tibolone | Livial | Tablet | 1.25–2.5 mg/day | |

| Prasterone (DHEA)b | – | Tablet | 10–100 mg/day | |

| Sublingual | Methyltestosterone | Metandren | Tablet | 0.25 mg/day |

| Transdermal | Testosterone | Intrinsa | Patch | 150–300 μg/day |

| AndroGel | Gel, cream | 1–10 mg/day | ||

| Vaginal | Prasterone (DHEA) | Intrarosa | Insert | 6.5 mg/day |

| Injection | Testosterone propionatea | Testoviron | Oil solution | 25 mg 1x/1–2 weeks |

| Testosterone enanthate | Delatestryl, Primodian Depot | Oil solution | 25–100 mg 1x/4–6 weeks | |

| Testosterone cypionate | Depo-Testosterone, Depo-Testadiol | Oil solution | 25–100 mg 1x/4–6 weeks | |

| Testosterone isobutyratea | Femandren M, Folivirin | Aqueous suspension | 25–50 mg 1x/4–6 weeks | |

| Mixed testosterone esters | Climacterona | Oil solution | 150 mg 1x/4–8 weeks | |

| Omnadren, Sustanon | Oil solution | 50–100 mg 1x/4–6 weeks | ||

| Nandrolone decanoate | Deca-Durabolin | Oil solution | 25–50 mg 1x/6–12 weeks | |

| Prasterone enanthatea | Gynodian Depot | Oil solution | 200 mg 1x/4–6 weeks | |

| Implant | Testosterone | Testopel | Pellet | 50–100 mg 1x/3–6 months |

| Notes: Premenopausal women produce about 230 ± 70 μg testosterone per day (6.4 ± 2.0 mg testosterone per 4 weeks), with a range of 130 to 330 μg per day (3.6–9.2 mg per 4 weeks). Footnotes: a = Mostly discontinued or unavailable. b = Over-the-counter. Sources: See template. | ||||

Childbirth

As the sodium salt of prasterone sulfate (brand names Astenile, Mylis, Teloin),[21][22] an ester prodrug of prasterone, prasterone is used in Japan as an injection for the treatment of insufficient cervical ripening and cervical dilation during childbirth.[1][23][24][25][26][27][28]

Available forms

Prasterone was previously marketed as a medication under the brand name Diandrone in the form of a 10 mg oral tablet in the United Kingdom.[29]

Side effects

Prasterone is produced naturally in the human body, but the long-term effects of its use are largely unknown.[30][31] In the short term, several studies have noted few adverse effects. In a study by Chang et al., prasterone was administered at a dose of 200 mg/day for 24 weeks with slight androgenic effects noted.[32] Another study utilized a dose up to 400 mg/day for 8 weeks with few adverse events reported.[33] A longer-term study followed patients dosed with 50 mg of prasterone for 12 months with the number and severity of side effects reported to be small.[34] Another study delivered a dose of 50 mg of prasterone for 10 months with no serious adverse events reported.[35]

As a hormone precursor, there have been reports of side effects possibly caused by the hormone metabolites of prasterone.[31][36]

It is not known whether prasterone is safe for long-term use. Some researchers believe prasterone supplements might actually raise the risk of breast cancer, prostate cancer, heart disease, diabetes,[31] and stroke. Prasterone may stimulate tumor growth in types of cancer that are sensitive to hormones, such as some types of breast, uterine, and prostate cancer.[31] Prasterone may increase prostate swelling in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), an enlarged prostate gland.[30]

Prasterone is a steroid hormone. High doses may cause aggressiveness, irritability, trouble sleeping, and the growth of body or facial hair on women.[30] It also may stop menstruation and lower the levels of HDL ("good" cholesterol), which could raise the risk of heart disease.[30] Other reported side effects include acne, heart rhythm problems, liver problems, hair loss (from the scalp), and oily skin. It may also alter the body's regulation of blood sugar.[30]

Prasterone may promote tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer.[30] It may also increase the risk of uterine and prostate cancers due to metabolism into estrogens and androgens, respectively.[37] Patients on hormone replacement therapy may have more estrogen-related side effects when taking prasterone. This supplement may also interfere with other medicines, and potential interactions between it and drugs and herbs are possible.[30]

Prasterone is possibly unsafe for individuals experiencing pregnancy, breastfeeding, hormone sensitive conditions, liver problems, diabetes, depression or mood disorders, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), or cholesterol problems.[38]

Prasterone has been reported to possess few or no side effects even at very high dosages (e.g., 50 times the recommended over-the-counter supplement dosage).[37] However, it may cause masculinization and other androgenic side effects in women and gynecomastia and other estrogenic side effects in men.[37]

Pharmacology

Prasterone is metabolized into androgens and estrogens in the body.[9][43] It is transformed into androstenedione by 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) and into androstenediol by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD).[9][43] Then, androstenedione and androstenediol can be converted into testosterone by 17β-HSD and 3β-HSD, respectively.[9][43] Subsequently, testosterone can be metabolized into dihydrotestosterone by 5α-reductase.[9][43] In addition, androstenedione and testosterone can be converted into estrone and estradiol by aromatase, respectively.[9][43] Prasterone is also reversibly transformed into prasterone sulfate by steroid sulfotransferase (specifically SULT1E1 and SULT2A1), which in turn can be converted back into prasterone by steroid sulfatase.[9][44] The transformation of prasterone into androgens and estrogens is tissue-specific, occurring for instance in the liver, fat, vagina, prostate gland, skin, and hair follicles, among other tissues.[9][45]

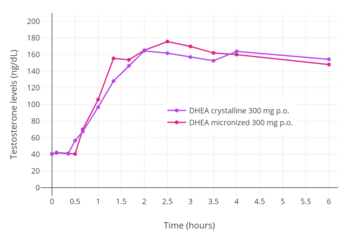

In clinical studies of prasterone supplementation, dosages have ranged from 20 to 1,600 mg per day.[46] In people with adrenal insufficiency, oral dosages of 20 to 50 mg/day prasterone have been found to restore DHEA and DHEA-S levels to normal ranges seen in healthy young adults.[46] Conversely, oral dosages of 100 to 200 mg/day prasterone have been found to result in supraphysiological levels of DHEA and DHEA-S.[46] At a high dosage of 1,600 mg/day orally for 4 weeks, treatment of postmenopausal women with prasterone has been found to increase serum levels of DHEA by 15-fold, testosterone by 9-fold, DHEA-S, androstenedione, and DHT all by 20-fold, and estrone and estradiol both by 2-fold.[47][48] Micronization of prasterone has been found to significantly increase levels of DHEA-S achieved with oral administration but to produce no significant change in levels of DHEA or testosterone levels achieved.[39]

Although prasterone can reliably increase testosterone levels in women, this isn't similarly the case in men.[37] A high dosage of 1,600 mg/day prasterone in men for 4 weeks was found to increase DHEA and androstenedione levels but did not significantly affect testosterone levels.[37]

Chemistry

Prasterone, also known as androst-5-en-3β-ol-17-one, is a naturally occurring androstane steroid and a 17-ketosteroid. It is closely related structurally to androstenediol (androst-5-ene-3β,17β-diol), androstenedione (androst-4-ene-3,17-dione), and testosterone (androst-4-en-17β-ol-3-one). Prasterone is the δ5 (5(6)-dehydrogenated) analogue of epiandrosterone (5α-androstan-3β-ol-17-one), and is also known as 5-dehydroepiandrosterone (5-DHEA) or δ5-epiandrosterone. A positional isomer of prasterone which may have similar biological activity is 4-dehydroepiandrosterone (4-DHEA).[49]

Derivatives

Prasterone is used medically as the C3β esters prasterone enanthate and prasterone sulfate.[1] The C19 demethyl analogue of prasterone is 19-nordehydroepiandrosterone (19-nor-DHEA), which is a prohormone of nandrolone (19-nortestosterone).[50][51] The 5α-reduced and δ1 (1(2)-dehydrogenated) analogue of prasterone is 1-dehydroepiandrosterone (1-DHEA or 1-androsterone), which is a prohormone of 1-testosterone (δ1-DHT or dihydroboldenone).[52] Fluasterone (3β-dehydroxy-16α-fluoro-DHEA) is a derivative of prasterone with minimal or no hormonal activity but other biological activities preserved.[47]

History

DHEA was discovered, via isolation from male urine, by Adolf Butenandt and Hans Dannenbaum in 1934, and the compound was isolated from human blood plasma by Migeon and Plager in 1954.[7][5] DHEA sulfate, the 3β-sulfate ester of DHEA, was isolated from urine in 1944, and was found by Baulieu to be the most abundant steroid hormone in human plasma in 1954.[7][5] From its discovery in 1934 until 1959, DHEA was referred to by a number of different names in the literature, including dehydroandrosterone, transdehydroandrosterone, dehydroisoandrosterone, and androstenolone.[5] The name dehydroepiandrosterone, also known as DHEA, was first proposed by Fieser in 1949, and subsequently became the most commonly used name of the hormone.[5] For decades after its discovery, DHEA was considered to be an inactive compound that served mainly as an intermediate in the production of androgens and estrogens from cholesterol.[5] In 1965, an association between DHEA sulfate levels and aging was reported by De Nee and Vermeulen.[7][5] Following this, DHEA became of interest to the scientific community, and numerous studies assessing the relationship between DHEA and DHEA sulfate levels and aging were conducted.[7][5]

Prasterone, the proposed INN and recommended INN of DHEA and the term used when referring to the compound as a medication, were published in 1970 and 1978, respectively.[53][54] The combination of 4 mg estradiol valerate and 200 mg prasterone enanthate in an oil solution was introduced for use in menopausal hormone therapy by intramuscular injection under the brand name Gynodian Depot in Europe by 1978.[55][56][57][58] In the early 1980s, prasterone became available and was widely sold over-the-counter as a non-prescription supplement in the United States, primarily as a weight loss aid.[7][5][59] It was described as a "miracle drug", with supposed anti-aging, anti-obesity, and anti-cancer benefits.[7] This continued until 1985, when the marketing of prasterone was banned by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) due to a lack of evidence for health benefits and due to the long-term safety and risks of the compound being unknown at the time.[7][5][59] Subsequently, prasterone once again became available over-the-counter as a dietary supplement in the United States following the passage of the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994.[7] Conversely, it has remained banned as a supplement in Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.[7][60]

In 2001, Genelabs submitted a New Drug Application of prasterone for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) to the FDA.[7][61] It had the tentative brand names Anastar, Aslera, and Prestara.[7][62][61] However, this application was not approved, and while development of prasterone for SLE in both the United States and Europe continued until up to 2010, the medication was ultimately never approved for the treatment of this condition.[7] In 2016, the FDA approved prasterone in an intravaginal gel formulation for the treatment of painful sexual intercourse due to vulvovaginal atrophy in the United States under the brand name Intrarosa.[63][64] This was the first prasterone-containing medication to be approved by the FDA in this country.[63]

Society and culture

Names

Prasterone is the generic name of DHEA in English and Italian and its International Nonproprietary Name, United States Adopted Name and Italian Common Name,[1][65][66][67] while its generic name is prasteronum in Latin, prastérone in French and its French popular name, and prasteron in German.[66]

It is sold under a number of brand names including Astenile, Cetovister, 17-Chetovis, Dastonil S, Deandros, Diandrone, Fidelin, Hormobago, 17-Hormoforin, Intrarosa, 17-Ketovis, Mentalormon, and Psicosterone.[1]

Marketing

In the United States, prasterone or prasterone sulfate have been advertised, under the names DHEA and DHEA-S, with claims that they may be beneficial for a wide variety of ailments. Prasterone and prasterone sulfate are readily available in the United States, where they are sold as over-the-counter dietary supplements.[68]

In 1996, reporter Harry Wessel of the Orlando (Florida) Sentinel wrote about DHEA that "Thousands of people have gotten caught up in the hoopla and are buying the stuff in health food stores, pharmacies and mail-order catalogs" but that "such enthusiasm is viewed as premature by many in the medical field." He noted that "National publications such as Time, Newsweek and USA Today have run articles recently about the hormone, while several major publishers have come out with books touting it."[69] His column was widely syndicated and reprinted in other U.S. newspapers.

The product was being "widely marketed to and used by bodybuilders," Dr. Paul Donahue wrote in 2012 for King Features syndicate.[70]

Regulation

Australia

In Australia, a prescription is required to buy prasterone, where it is also comparatively expensive compared to off-the-shelf purchases in US supplement shops. Australian customs classify prasterone as an "anabolic steroid[s] or precursor[s]" and, as such, it is only possible to carry prasterone into the country through customs if one possesses an import permit which may be obtained if one has a valid prescription for the hormone.[71]

Canada

In Canada, prasterone is a Controlled Drug listed under Section 23 of Schedule IV of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act[72] and as such is available by prescription only.

United Kingdom

Prasterone is listed as an anabolic steroid and is thus a class C controlled drug.

United States

Prasterone is legal to sell in the United States as a dietary supplement. It is currently grandfathered in as an "Old Dietary Ingredient" being on sale prior to 1994. Prasterone is specifically exempted from the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 1990 and 2004.[73]

Sports

Prasterone is banned from use in athletic competition. [7][5][59] It is a prohibited substance under the World Anti-Doping Code of the World Anti-Doping Agency,[74] which manages drug testing for Olympics and other sports.

- Yulia Efimova, who holds the world record pace for both the 50-meter and 200-meter breaststroke, and won the bronze medal in the 200-meter breaststroke in the 2012 London Olympic Games, tested positive for prasterone in an out-of-competition doping test.[75]

- Rashard Lewis, then with the Orlando Magic, tested positive for prasterone and was suspended 10 games before the start of the 2009–10 season.[76]

- In 2016 MMA fighter Fabio Maldonado revealed he was taking prasterone during his time with the UFC.[77]

- In January 2011, NBA player O. J. Mayo was given a 10-game suspension after testing positive for prasterone. Mayo termed his use of prasterone as "an honest mistake," saying the prasterone was in an over-the-counter supplement and that he was unaware the supplement was banned by the NBA.[78] Mayo was the seventh player to test positive for performance-enhancing drugs since the league began testing in 1999.

- Olympic 400-meter champion Lashawn Merritt tested positive for prasterone in 2010 and was banned from the sport for 21 months.[79]

- Tennis player Venus Williams had permission from the International Tennis Federation to use DHEA along with hydrocortisone as a treatment for "adrenal insufficiency," but it was revoked in 2016 by the World Anti-Doping Agency, which believed DHEA use would enhance Williams' athletic performance.[80]

Research

Anabolic uses

A meta-analysis of intervention studies shows that prasterone supplementation in elderly men can induce a small but significant positive effect on body composition that is strictly dependent on prasterone conversion into its bioactive metabolites such as androgens or estrogens.[81] Evidence is inconclusive in regards to the effect of prasterone on strength in the elderly.[82] In middle-aged men, no significant effect of prasterone supplementation on lean body mass, strength, or testosterone levels was found in a randomized placebo-controlled trial.[83]

Cancer

There is no evidence prasterone is of benefit in treating or preventing cancer.[30]

Heart disease

A review in 2003 found that low serum levels of DHEA-S is associated with coronary heart disease in men, but insufficient to determine whether prasterone supplementation would have any benefit.[84]

Prasterone may enhance G6PD mRNA expression, confounding its inhibitory effects.[85]

Lupus

There is some evidence of short-term benefit in those with systemic lupus erythematosus but little evidence of long-term benefit or safety.[86] Prasterone was under development for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States and Europe in the 1990s and 2000s and reached phase III clinical trials and preregistration for this indication, respectively, but ultimately development was not continued past 2010.[7][62][61]

Memory

Prasterone supplementation has not been found to be useful for memory function in normal middle aged or older adults.[87] It has been studied as a treatment for Alzheimer's disease, but there is no evidence that it is effective or ineffective. More research is needed to determine it's benefits..[88]

Mood

A few small, short term clinical studies have found that prasterone improves mood but its long-term efficacy and safety, and how it compares to antidepressants, was unknown as of 2015.[89][90]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 641–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ James Devillers (27 April 2009). Endocrine Disruption Modeling. CRC Press. pp. 339–. ISBN 978-1-4200-7636-3. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 "Intrarosa". Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 879. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 Rutkowski K, Sowa P, Rutkowska-Talipska J, Kuryliszyn-Moskal A, Rutkowski R (July 2014). "Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): hypes and hopes". Drugs. 74 (11): 1195–207. doi:10.1007/s40265-014-0259-8. PMID 25022952. S2CID 26554413.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Prasterone Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24 7.25 Melanie Johns Cupp; Timothy S. Tracy (10 December 2002). Dietary Supplements: Toxicology and Clinical Pharmacology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 123–147. ISBN 978-1-59259-303-3. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 B.J. Oddens; A. Vermeulen (15 November 1996). Androgens and the Aging Male. CRC Press. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-1-85070-763-9. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Prough RA, Clark BJ, Klinge CM (April 2016). "Novel mechanisms for DHEA action". J. Mol. Endocrinol. 56 (3): R139–55. doi:10.1530/JME-16-0013. PMID 26908835.

- ↑ "Prasterone vaginal - Bayer/Endoceutics - AdisInsight". Archived from the original on 2018-01-04. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Archive copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-03-31. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Arlt, W (September 2004). "Dehydroepiandrosterone and ageing". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 18 (3): 363–80. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2004.02.006. PMID 15261843.

- ↑ Alkatib, AA; Cosma, M; Elamin, MB; Erickson, D; Swiglo, BA; Erwin, PJ; Montori, VM (October 2009). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials of DHEA treatment effects on quality of life in women with adrenal insufficiency". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 94 (10): 3676–81. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-0672. PMID 19773400.

- ↑ Rogerio A. Lobo (5 June 2007). Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Academic Press. pp. 821–828. ISBN 978-0-08-055309-2. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ "Gynodian Depot". Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ J. Horsky; J. Presl (6 December 2012). Ovarian Function and its Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-94-009-8195-9. Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ D. Platt (6 December 2012). Geriatrics 3: Gynecology · Orthopaedics · Anesthesiology · Surgery · Otorhinolaryngology · Ophthalmology · Dermatology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-3-642-68976-5. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ S. Campbell (6 December 2012). The Management of the Menopause & Post-Menopausal Years: The Proceedings of the International Symposium held in London 24–26 November 1975 Arranged by the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of London. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 395–. ISBN 978-94-011-6165-7. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ Carrie Bagatell; William J. Bremner (27 May 2003). Androgens in Health and Disease. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-1-59259-388-0. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ Frigo P, Eppel W, Asseryanis E, Sator M, Golaszewski T, Gruber D, Lang C, Huber J (1995). "The effects of hormone substitution in depot form on the uterus in a group of 50 perimenopausal women--a vaginosonographic study". Maturitas. 21 (3): 221–5. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(94)00893-c. PMID 7616871.

- ↑ "Prasterone Monograph for Professionals". Archived from the original on 2018-01-04. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ "Prasterone vaginal - Kanebo - AdisInsight". Archived from the original on 2018-01-04. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ John W. Blunt; Murray H. G. Munro (19 September 2007). Dictionary of Marine Natural Products with CD-ROM. CRC Press. pp. 1075–. ISBN 978-0-8493-8217-8. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ A. Kleemann; J. Engel; B. Kutscher; D. Reichert (14 May 2014). Pharmaceutical Substances, 5th Edition, 2009: Syntheses, Patents and Applications of the most relevant APIs. Thieme. pp. 2441–2442. ISBN 978-3-13-179525-0. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ Martin Negwer; Hans-Georg Scharnow (2001). Organic-chemical drugs and their synonyms: (an international survey). Wiley-VCH. p. 1831. ISBN 978-3-527-30247-5. Archived from the original on 2020-06-08. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

3β-Hydroxyandrost-5-en-17-one hydrogen sulfate = (3β)-3-(Sulfooxy)androst-5-en-17-one. R: Sodium salt (1099-87-2). S: Astenile, Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate sodium, DHA-S, DHEAS, KYH 3102, Mylis, PB 005, Prasterone sodium sulfate, Teloin

- ↑ Jianqiu, Y (1992). "Clinical Application of Prasterone Sodium Sulfate". Chinese Journal of New Drugs. 5: 015.

- ↑ Sakaguchi M, Sakai T, Adachi Y, Kawashima T, Awata N (1992). "The biological fate of sodium prasterone sulfate after vaginal administration. I. Absorption and excretion in rats". J. Pharmacobio-Dyn. 15 (2): 67–73. doi:10.1248/bpb1978.15.67. PMID 1403604.

- ↑ Sakai, T.; Sakaguchi, M.; Adachi, Y.; Kawashima, T.; Awata, N. (1992). "The Biological Fate of Sodium Prasterone Sulfate after Vaginal Administration II: Distribution after Single and Multiple Administration to Pregnant Rats". 薬物動態. 7 (1): 87–101. doi:10.2133/dmpk.7.87.

- ↑ Janet Brotherton (1976). Sex Hormone Pharmacology. Academic Press. pp. 19, 336. ISBN 978-0-12-137250-7.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 30.7 Ades TB, ed. (2009). DHEA. American Cancer Society Complete Guide to Complementary and Alternative Cancer Therapies (2nd ed.). American Cancer Society. pp. 729–33. ISBN 9780944235713.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Medscape (2010). "DHEA Oral". Drug Reference. WebMD LLC. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ Chang DM, Lan JL, Lin HY, Luo SF (2002). "Dehydroepiandrosterone treatment of women with mild-to-moderate systemic lupus erythematosus: a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Arthritis Rheum. 46 (11): 2924–27. doi:10.1002/art.10615. PMID 12428233.

- ↑ Rabkin JG, McElhiney MC, Rabkin R, McGrath PJ, Ferrando SJ (2006). "Placebo-controlled trial of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) for treatment of nonmajor depression in patients with HIV/AIDS". Am J Psychiatry. 163 (1): 59–66. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.59. PMID 16390890.

- ↑ Brooke AM, Kalingag LA, Miraki-Moud F, Camacho-Hübner C, Maher KT, Walker DM, Hinson JP, Monson JP (2006). "Dehydroepiandrosterone improves psychological well-being in male and female hypopituitary patients on maintenance growth hormone replacement". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 91 (10): 3773–79. doi:10.1210/jc.2006-0316. PMID 16849414.

- ↑ Villareal DT, Holloszy JO (2006). "DHEA enhances effects of weight training on muscle mass and strength in elderly women and men". Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 291 (5): E1003–08. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00100.2006. PMID 16787962. S2CID 8929382. Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ Medline Plus. "DHEA". Drugs and Supplements Information. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 22 February 2010. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 Douglas McKeag; James L. Moeller (2007). ACSM's Primary Care Sports Medicine. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 616–. ISBN 978-0-7817-7028-6. Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ "DHEA: Side effects and safety". WebMD. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Casson PR, Straughn AB, Umstot ES, Abraham GE, Carson SA, Buster JE (February 1996). "Delivery of dehydroepiandrosterone to premenopausal women: effects of micronization and nonoral administration". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 174 (2): 649–53. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70444-1. PMID 8623801.

- ↑ Kuhl, Herbert; Taubert, Hans-Dieter (1987). Das Klimakterium – Pathophysiologie, Klinik, Therapie [The Climacteric – Pathophysiology, Clinic, Therapy] (in Deutsch). Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme Verlag. p. 122. ISBN 978-3137008019.

- ↑ Düsterberg B, Wendt H (1983). "Plasma levels of dehydroepiandrosterone and 17 beta-estradiol after intramuscular administration of Gynodian-Depot in 3 women". Horm. Res. 17 (2): 84–9. doi:10.1159/000179680. PMID 6220949.

- ↑ Rauramo L, Punnonen R, Kaihola LH, Grönroos M (January 1980). "Serum oestrone, oestradiol and oestriol concentrations in castrated women during intramuscular oestradiol valerate and oestradiolbenzoate-oestradiolphenylpropionate therapy". Maturitas. 2 (1): 53–8. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(80)90060-2. PMID 7402086.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 Carl A. Burtis; Edward R. Ashwood; David E. Bruns (14 October 2012). Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1856–. ISBN 978-1-4557-5942-2. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ Mueller JW, Gilligan LC, Idkowiak J, Arlt W, Foster PA (2015). "The Regulation of Steroid Action by Sulfation and Desulfation". Endocr. Rev. 36 (5): 526–63. doi:10.1210/er.2015-1036. PMC 4591525. PMID 26213785.

- ↑ Labrie F, Martel C, Bélanger A, Pelletier G (April 2017). "Androgens in women are essentially made from DHEA in each peripheral tissue according to intracrinology". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 168: 9–18. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.12.007. PMID 28153489. S2CID 2620899.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Paul M. Coates; M. Coates Paul; Marc Blackman; Marc R. Blackman, Gordon M. Cragg, Mark Levine, Jeffrey D. White, Joel Moss, Mark A. Levine (29 December 2004). Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements (Print). CRC Press. pp. 169–. ISBN 978-0-8247-5504-1. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 47.0 47.1 Schwartz AG, Pashko LL (2004). "Dehydroepiandrosterone, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and longevity". Ageing Res. Rev. 3 (2): 171–87. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2003.05.001. PMID 15177053. S2CID 11871872.

- ↑ Mortola JF, Yen SS (1990). "The effects of oral dehydroepiandrosterone on endocrine-metabolic parameters in postmenopausal women". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 71 (3): 696–704. doi:10.1210/jcem-71-3-696. PMID 2144295.

- ↑ Edith Josephy; F. Radt (1 December 2013). Elsevier's Encyclopaedia of Organic Chemistry: Series III: Carboisocyclic Condensed Compounds. Springer. pp. 2608–. ISBN 978-3-662-25863-7. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ NSCA-National Strength & Conditioning Association (27 January 2017). NSCA'S Essentials of Tactical Strength and Conditioning. Human Kinetics. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-1-4504-5730-9. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ Detlef Thieme; Peter Hemmersbach (18 December 2009). Doping in Sports. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-3-540-79088-4. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ Parr MK, Opfermann G, Geyer H, Westphal F, Sönnichsen FD, Zapp J, Kwiatkowska D, Schänzer W (2011). "Seized designer supplement named "1-Androsterone": identification as 3β-hydroxy-5α-androst-1-en-17-one and its urinary elimination". Steroids. 76 (6): 540–7. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2011.02.001. PMID 21310167. S2CID 4942690.

- ↑ "School of INN" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ "School of INN" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ Hoyme U, Baumueller A, Madsen PO (1978). "The influence of pH on antimicrobial substances in canine vaginal and urethral secretions". Urol. Res. 6 (1): 35–42. doi:10.1007/bf00257080. PMID 25506. S2CID 8266978.

- ↑ Kopera, H.; Dhont, M.; Dienstl, F.; Gambrell, R. D.; Gordan, G. S.; Heidenreich, J.; Lachnit-Fixon, U.; Lauritzen, C.; Lebech, P. E.; Sitruk-Ware, R. L.; Utian, W. H. (1979). "Effects, side-effects, and dosage schemes of various sex hormones in the peri- and post-menopause". Female and Male Climacteric. pp. 43–67. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-9720-5_6. ISBN 978-94-011-9722-9.

- ↑ Mattson LA, Cullberg G, Tangkeo P, Zador G, Samsioe G (December 1980). "Administration of dehydroepiandrosterone enanthate to oophorectomized women--effects on sex hormones and lipid metabolism". Maturitas. 2 (4): 301–9. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(80)90032-8. PMID 6453267.

- ↑ Muller (19 June 1998). European Drug Index: European Drug Registrations, Fourth Edition. CRC Press. pp. 566–. ISBN 978-3-7692-2114-5. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 C.W. Randolph, Jr., M.D.; Genie James (1 January 2010). From Hormone Hell to Hormone Well: Straight Talk Women (and Men) Need to Know to Save Their Sanity, Health, and—Quite Possibly—Their Lives. Health Communications, Incorporated. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-7573-9759-2. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Marie Dunford; J. Andrew Doyle (7 February 2014). Nutrition for Sport and Exercise. Cengage Learning. pp. 442–. ISBN 978-1-285-75249-5. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 "Prasterone - Genelabs - AdisInsight". Archived from the original on 2017-10-15. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Sheldon Blau; Dodi Schultz (5 March 2009). Living With Lupus: The Complete Guide, 2nd Edition. Da Capo Press. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-7867-2985-2. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Voelker, Rebecca (2017). "Relief for Painful Intercourse". JAMA. 317 (1): 18. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.19077. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 28030684.

- ↑ "Prasterone (Intrarosa) for Dyspareunia". JAMA. 318 (16): 1607–1608. 2017. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.14981. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 29067420. S2CID 43211499.

- ↑ I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 92, 96, 230. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "Prasterone". Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ "Drug Information Portal - U.S. National Library of Medicine - Quick Access to Quality Drug Information". Archived from the original on 2021-10-11. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ Calfee, R.; Fadale, P. (March 2006). "Popular ergogenic drugs and supplements in young athletes". Pediatrics. 117 (3): e577–89. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1429. PMID 16510635.

In 2004, a new Steroid Control Act that placed androstenedione under Schedule III of controlled substances effective January 2005 was signed. DHEA was not included in this act and remains an over-the-counter nutritional supplement.

- ↑ ""Proponents Say DHEA Blunts Effects of Aging," Orlando Sentinel, image 43". Archived from the original on 2020-07-19. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ ""DHEA Supplement a Help or Harm," Kenosha (Wisconsin) News, March 18, 2012, image 17". Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Therapeutic Goods Administration, Personal Importation Scheme". Archived from the original on 2014-10-22. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ "Health Canada, DHEA listing in the Ingredient Database". Archived from the original on 2020-11-26. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ "Drug Scheduling Actions – 2005". Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on 2012-02-16. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ "World Anti-Doping Agency". Archived from the original on 2013-05-01. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ "Russian Olympic Medal-Winning Swimmer Efimova Fails Doping Test – Report". Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ "Memphis Grizzlies' O. J. Mayo suspended 10 games for violating NBA anti-drug program". Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ "Fabio Maldonado plans to use DHEA for Fedor match, admits use in UFC". Archived from the original on 2020-11-08. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ↑ Memphis Grizzlies' O. J. Mayo gets 10-game drug suspension Archived 2012-05-12 at the Wayback Machine, ESPN, January 27, 2011.

- ↑ "US 400m star LaShawn Merritt fails drug test". BBC Sport. 22 April 2010. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ "Rebecca R. Ruiz and Ben Rothenberg, "Doping," Austin American-Statesman, Texas, September 22, 2016, page C12, from The New York Times". Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ↑ Corona, G; Rastrelli, G; Giagulli, VA; Sila, A; Sforza, A; Forti, G; Mannucci, E; Maggi, M (2013). "Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation in elderly men: a meta-analysis study of placebo-controlled trials". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98 (9): 3615–26. doi:10.1210/jc.2013-1358. PMID 23824417.

- ↑ Baker, WL; Karan, S; Kenny, AM (June 2011). "Effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on muscle strength and physical function in older adults: a systematic review". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 59 (6): 997–1002. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03410.x. PMID 21649617. S2CID 7137809.

- ↑ Wallace, M. B.; Lim, J.; Cutler, A.; Bucci, L. (1999). "Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone vs androstenedione supplementation in men". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 31 (12): 1788–92. doi:10.1097/00005768-199912000-00014. PMID 10613429.

- ↑ Thijs L, Fagard R, Forette F, Nawrot T, Staessen JA (October 2003). "Are low dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate levels predictive for cardiovascular diseases? A review of prospective and retrospective studies". Acta Cardiol. 58 (5): 403–10. doi:10.2143/AC.58.5.2005304. PMID 14609305. S2CID 32786778.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Hecker PA, Leopold JA, Gupte SA, Recchia FA, Stanley WC (Feb 2013). "Impact of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency on the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease". Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 304 (4): H491–500. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00721.2012. PMC 3566485. PMID 23241320.

- ↑ Crosbie, D; Black, C; McIntyre, L; Royle, PL; Thomas, S (Oct 17, 2007). Crosbie, David (ed.). "Dehydroepiandrosterone for systemic lupus erythematosus". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD005114. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005114.pub2. PMID 17943841.

- ↑ Grimley Evans, J; Malouf, R; Huppert, F; van Niekerk, JK (Oct 18, 2006). Malouf, Reem (ed.). "Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation for cognitive function in healthy elderly people". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006221. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006221. PMID 17054283.

- ↑ Fuller, SJ; Tan, RS; Martins, RN (September 2007). "Androgens in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease in aging men and possible therapeutic interventions". Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 12 (2): 129–42. doi:10.3233/JAD-2007-12202. PMID 17917157.

- ↑ Pluchino, N; Drakopoulos, P; Bianchi-Demicheli, F; Wenger, JM; Petignat, P; Genazzani, AR (January 2015). "Neurobiology of DHEA and effects on sexuality, mood and cognition". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 145: 273–80. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.04.012. PMID 24892797. S2CID 12382989.

- ↑ Maric, NP; Adzic, M (September 2013). "Pharmacological modulation of HPA axis in depression - new avenues for potential therapeutic benefits" (PDF). Psychiatria Danubina. 25 (3): 299–305. PMID 24048401. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- Prasterone vaginal - Bayer/Endoceutics - AdisInsight Archived 2018-01-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Prasterone vaginal - Kanebo - AdisInsight Archived 2018-01-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- CS1 Deutsch-language sources (de)

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 maint: url-status

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Androgens and anabolic steroids

- Androstanes

- Estrogens

- Dietary supplements

- GABAA receptor negative allosteric modulators

- Neurosteroids

- NMDA receptor agonists

- Pregnane X receptor agonists

- Prodrugs

- Sigma agonists

- World Anti-Doping Agency prohibited substances

- RTT