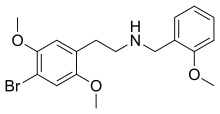

25B-NBOMe

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2022) |

| |

| Legal status | |

|---|---|

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H22BrNO3 |

| Molar mass | 380.282 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

25B-NBOMe (NBOMe-2C-B, Cimbi-36, Nova, BOM 2-CB) is a derivative of the phenethylamine psychedelic 2C-B, discovered in 2004 by Ralf Heim at the Free University of Berlin. It acts as a potent full agonist for the 5HT2A receptor.[3][4][5][6][7][excessive citations] Anecdotal reports from users[weasel words] suggest 25B-NBOMe to be an active hallucinogen at a dose of as little as 250–500 μg,[citation needed] making it a similar potency to other phenethylamine derived hallucinogens such as Bromo-DragonFLY. Duration of effects lasts about 12–16 hours[citation needed], although the parent compound is rapidly cleared from the blood when used in the radiolabeled form in tracer doses.[7] Recently, Custodio et al. (2019) evaluated the potential involvement of dysregulated dopaminergic system, neuroadaptation, and brain wave changes which may contribute to the rewarding and reinforcing properties of 25B-NBOMe in rodents.[8]

The carbon-11 labeled version of this compound ([11C]Cimbi-36) was synthesized and validated as a radioactive tracer for positron emission tomography (PET) in Copenhagen.[9][10][11][12][13][excessive citations] As a 5-HT2A receptor agonist PET radioligand, [11C]Cimbi-36 was hypothesized to provide a more functional marker of these receptors. Also, [11C]Cimbi-36 is investigated as a potential marker of serotonin release and thus could serve as an indicator of serotonin levels in vivo. [11C]Cimbi-36 is now undergoing clinical trials as a PET-ligand in humans.[14][15][16]

Toxicity and harm potential

NBOMe compounds are often associated with life-threatening toxicity and death.[17][18] Studies on NBOMe family of compounds demonstrated that the substance exhibit neurotoxic and cardiotoxic activity.[19] Reports of autonomic dysfunction remains prevalent with NBOMe compounds, with most individuals experiencing sympathomimetic toxicity such as vasoconstriction, hypertension and tachycardia in addition to hallucinations.[20][21][22][23][24] Other symptoms of toxidrome of include agitation or aggression, seizure, hyperthermia, diaphoresis, hypertonia, rhabdomyolysis, and death.[20][24][18] Researchers report that NBOMe intoxication frequently display signs of serotonin syndrome.[25] The likelihood of seizure is higher in NBOMes compared to other psychedelics.[19]

NBOMe and NBOHs are regularly sold as LSD in blotter papers,[18][26] which have a bitter taste and different safety profiles.[20][17] Despite high potency, recreational doses of LSD have only produced low incidents of acute toxicity.[17] Fatalities involved in NBOMe intoxication suggest that a significant number of individuals ingested the substance which they believed was LSD,[22] and researchers report that "users familiar with LSD may have a false sense of security when ingesting NBOMe inadvertently".[20] While most fatalities are due to the physical effects of the drug, there have also been reports of death due to self-harm and suicide under the influence of the substance.[27][28][20]

Given limited documentation of NBOMe consumption, the long-term effects of the substance remain unknown.[20] NBOMe compounds are not active orally,[a] and are usually taken sublingually.[30]: 3 When NBOMes are administered sublingually, numbness of the tongue and mouth followed by a metallic chemical taste was observed, and researchers describe this physical side effect as one of the main discriminants between NBOMe compounds and LSD.[31][32][33]Neurotoxic and cardiotoxic actions

Many of the NBOMe compounds have high potency agonist activity at additional 5-HT receptors and prolonged activation of 5-HT2B can cause cardiac valvulopathy in high doses and chronic use.[18][23] 5-HT2B receptors have been strongly implicated in causing drug-induced valvular heart disease.[34][35][36] The high affinity of NBOMe compounds for adrenergic α1 receptor has been reported to contribute to the stimulant-type cardiovascular effects.[23]

In vitro studies, 25C-NBOMe has been shown to exhibit cytotoxicity on neuronal cell lines SH-SY5Y, PC12, and SN471, and the compound was more potent than methamphetamine at reducing the visibility of the respective cells; the neurotoxicity of the compound involves activation of MAPK/ERK cascade and inhibition of Akt/PKB signaling pathway.[19] 25C-NBOMe, including the other derivative 25D-NBOMe, reduced the visibility of cardiomyocytes H9c2 cells, and both substances downregulated expression level of p21 (CDC24/RAC)-activated kinase 1 (PAK1), an enzyme with documented cardiac protective effects.[19]

Preliminary studies on 25C-NBOMe have shown that the substance is toxic to development, heart health, and brain health in zebrafish, rats, and Artemia salina, a common organism for studying potential drug effects on humans, but more research is needed on the topic, the dosages, and if the toxicology results apply to humans. Researchers of the study also recommended further investigation of the drug's potential in damaging pregnant women and their fetus due to the substance's damaging effects to development.[37][38]Emergency treatment

Analogues and derivatives

Analogues and derivatives of 2C-B:

25-N:

- 25B-NB

- 25B-NB23DM

- 25B-NB25DM

- 25B-NB3OMe

- 25B-NB4OMe

- 25B-NBF

- 25B-NBMD

- 25B-NBOH

- 25B-NBOMe (NBOMe-2CB)

- 2C-B-FLY

- 2CBFly-NBOMe (NBOMe-2CB-Fly)

- DOB-FLY

- DOB-2-DRAGONFLY-5-BUTTERFLY

Other:

- BOB

- BOH-2C-B, β-Hydroxy-2C-B, βOH-2CB[41][42]

- BMB

- 2C-B-5-hemifly

- 2C-B-aminorex (2C-B-AR)

- 2C-B-AN

- 2C-B-BZP

- 2C-B-FLY-NB2EtO5Cl

- 2C-B-PP

- 2CB-Ind

- βk-2C-B (beta-keto 2C-B)

- N-Ethyl-2C-B

- TCB-2 (2C-BCB)

Legal status

Canada

As of October 31, 2016; 25B-NBOMe is a controlled substance (Schedule III) in Canada.[43]

Russia

Banned as a narcotic drug since May 5, 2015.[44]

Sweden

In Sweden, the Riksdag added 25B-NBOMe to schedule I ("substances, plant materials and fungi which normally do not have medical use") as narcotics in Sweden as of August 1, 2013, published by the Medical Products Agency in their regulation LVFS 2013:15 listed as 25B-NBOMe 2-(4-bromo-2,5-dimetoxifenyl)-N-(2-metoxibensyl)etanamin.[45]

United Kingdom

This substance is a Class A drug in the United Kingdom as a result of the N-benzylphenethylamine catch-all clause in the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.[46]

United States

In November 2013, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration placed 25B-NBOMe (along with 25I-NBOMe and 25C-NBOMe) in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act, making it illegal to manufacture, buy, possess, process, or distribute.[47]

China

As of October 2015 25B-NBOMe is a controlled substance in China.[48]

Czech Republic

25B-NBOMe is banned in the Czech Republic.[49]

Notes

- ^ The potency of N-benzylphenethylamines via buccal, sublingual, or nasal absorption is 50-100 greater (by weight) than oral route compared to the parent 2C-x compounds.[29] Researchers hypothesize the low oral metabolic stability of N-benzylphenethylamines is likely causing the low bioavailability on the oral route, although the metabolic profile of this compounds remains unpredictable; therefore researchers state that the fatalities linked to these substances may partly be explained by differences in the metabolism between individuals.[29]

References

- ^ Anvisa (July 24, 2023). "RDC Nº 804 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 804 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published July 25, 2023). Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ "Substance Details 25B-NBOMe". Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ Heim R (February 28, 2010). "Synthese und Pharmakologie potenter 5-HT2A-Rezeptoragonisten mit N-2-Methoxybenzyl-Partialstruktur. Entwicklung eines neuen Struktur-Wirkungskonzepts" (in German). diss.fu-berlin.de. Retrieved May 10, 2013.

- ^ Silva M (2009). Theoretical study of the interaction of agonists with the 5-HT2A receptor (Ph.D. thesis). Universität Regensburg.

- ^ Silva ME, Heim R, Strasser A, Elz S, Dove S (January 2011). "Theoretical studies on the interaction of partial agonists with the 5-HT2A receptor". Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 25 (1): 51–66. Bibcode:2011JCAMD..25...51S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.2670. doi:10.1007/s10822-010-9400-2. PMID 21088982. S2CID 3103050.

- ^ Hansen M, Phonekeo K, Paine JS, Leth-Petersen S, Begtrup M, Bräuner-Osborne H, Kristensen JL (March 2014). "Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of N-benzyl phenethylamines as 5-HT2A/2C agonists". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 5 (3): 243–9. doi:10.1021/cn400216u. PMC 3963123. PMID 24397362.

- ^ a b Ettrup A, da Cunha-Bang S, McMahon B, Lehel S, Dyssegaard A, Skibsted AW, et al. (July 2014). "Serotonin 2A receptor agonist binding in the human brain with [¹¹C]Cimbi-36". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 34 (7): 1188–96. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2014.68. PMC 4083382. PMID 24780897.

- ^ Custodio RJ, Sayson LV, Botanas CJ, Abiero A, You KY, Kim M, et al. (November 2020). "25B-NBOMe, a novel N-2-methoxybenzyl-phenethylamine (NBOMe) derivative, may induce rewarding and reinforcing effects via a dopaminergic mechanism: Evidence of abuse potential". Addiction Biology. 25 (6): e12850. doi:10.1111/adb.12850. PMID 31749223. S2CID 208217863.

- ^ Hansen M (December 16, 2010). Design and Synthesis of Selective Serotonin Receptor Agonists for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of the Brain (Ph.D. thesis). University of Copenhagen. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.33671.14245.

- ^ Ettrup A, Hansen M, Santini MA, Paine J, Gillings N, Palner M, Lehel S, Herth MM, Madsen J, et al. (April 2011). "Radiosynthesis and in vivo evaluation of a series of substituted 11C-phenethylamines as 5-HT (2A) agonist PET tracers". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 38 (4): 681–93. doi:10.1007/s00259-010-1686-8. PMID 21174090. S2CID 12467684.

- ^ Ettrup A, Holm S, Hansen M, Wasim M, Santini MA, Palner M, et al. (August 2013). "Preclinical safety assessment of the 5-HT2A receptor agonist PET radioligand [ 11C]Cimbi-36". Molecular Imaging and Biology. 15 (4): 376–383. doi:10.1007/s11307-012-0609-4. PMID 23306971. S2CID 1474367.

- ^ Johansen A, Hansen HD, Svarer C, Lehel S, Leth-Petersen S, Kristensen JL, et al. (April 2018). "The importance of small polar radiometabolites in molecular neuroimaging: A PET study with [11C]Cimbi-36 labeled in two positions". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 38 (4): 659–668. doi:10.1177/0271678X17746179. PMC 5888860. PMID 29215308.

- ^ Johansen A, Holm S, Dall B, Keller S, Kristensen JL, Knudsen GM, Hansen HD (July 2019). "Human biodistribution and radiation dosimetry of the 5-HT2A receptor agonist Cimbi-36 labeled with carbon-11 in two positions". EJNMMI Research. 9 (1): 71. doi:10.1186/s13550-019-0527-4. PMC 6669221. PMID 31367837.

- ^ "From molecule to man: The full CIMBI-36 story" (PDF). cimbi.dk. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ "Imanova announces the launch of a new imaging biomarker to investigate the serotonin system in psychiatric illness". imanova.co.uk. Archived from the original on April 9, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Madsen MK, Fisher PM, Burmester D, Dyssegaard A, Stenbæk DS, Kristiansen S, et al. (June 2019). "Psychedelic effects of psilocybin correlate with serotonin 2A receptor occupancy and plasma psilocin levels". Neuropsychopharmacology. 44 (7): 1328–1334. doi:10.1038/s41386-019-0324-9. PMC 6785028. PMID 30685771.

- ^ a b c Sean I, Joe R, Jennifer S, and Shaun G (March 28, 2022). "A cluster of 25B-NBOH poisonings following exposure to powder sold as lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)". Clinical Toxicology. 60 (8): 966–969. doi:10.1080/15563650.2022.2053150. PMID 35343858. S2CID 247764056.

- ^ a b c d Amy E, Katherine W, John R, Sonyoung K, Robert J, Aaron J (December 2018). "Neurochemical pharmacology of psychoactive substituted N-benzylphenethylamines: High potency agonists at 5-HT2A receptors". Biochemical Pharmacology. 158: 27–34. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2018.09.024. PMC 6298744. PMID 30261175.

- ^ a b c d e Jolanta Z, Monika K, and Piotr A (February 26, 2020). "NBOMes–Highly Potent and Toxic Alternatives of LSD". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 14: 78. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00078. PMC 7054380. PMID 32174803.

- ^ a b c d e f Lipow M, Kaleem SZ, Espiridion E (March 30, 2022). "NBOMe Toxicity and Fatalities: A Review of the Literature". Transformative Medicine. 1 (1): 12–18. doi:10.54299/tmed/msot8578. ISSN 2831-8978. S2CID 247888583.

- ^ Micaela T, Sabrine B, Raffaella A, Giorgia C, Beatrice M, Tatiana B, Federica B, Giovanni S, Francesco B, Fabio G, Krystyna G, Matteo M (April 21, 2022). "Effect of -NBOMe Compounds on Sensorimotor, Motor, and Prepulse Inhibition Responses in Mice in Comparison With the 2C Analogs and Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: From Preclinical Evidence to Forensic Implication in Driving Under the Influence of Drugs". Front Psychiatry. 13: 875722. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.875722. PMC 9069068. PMID 35530025.

- ^ a b Cristina M, Matteo M, Nicholas P, Maria C, Micaela T, Raffaella A, Maria L (December 12, 2019). "Neurochemical and Behavioral Profiling in Male and Female Rats of the Psychedelic Agent 25I-NBOMe". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 10: 1406. doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.01406. PMC 6921684. PMID 31915427.

- ^ a b c Anna R, Dino L, Julia R, Daniele B, Marius H, Matthias L (December 2015). "Receptor interaction profiles of novel N-2-methoxybenzyl (NBOMe) derivatives of 2,5-dimethoxy-substituted phenethylamines (2C drugs)". Neuropharmacology. 99: 546–553. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.08.034. ISSN 1873-7064. PMID 26318099. S2CID 10382311.

- ^ a b David W, Roumen S, Andrew C, Paul D (February 6, 2015). "Prevalence of use and acute toxicity associated with the use of NBOMe drugs". Clinical Toxicology. 53 (2): 85–92. doi:10.3109/15563650.2015.1004179. PMID 25658166. S2CID 25752763.

- ^ Humston C, Miketic R, Moon K, Ma P, Tobias J (June 5, 2017). "Toxic Leukoencephalopathy in a Teenager Caused by the Recreational Ingestion of 25I-NBOMe: A Case Report and Review of Literature". Journal of Medical Cases. 8 (6): 174–179. doi:10.14740/jmc2811w. ISSN 1923-4163.

- ^ Justin P, Stephen R, Kylin A, Alphonse P, Michelle P (2015). "Analysis of 25I-NBOMe, 25B-NBOMe, 25C-NBOMe and Other Dimethoxyphenyl-N-[(2-Methoxyphenyl) Methyl]Ethanamine Derivatives on Blotter Paper". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 39 (8): 617–623. doi:10.1093/jat/bkv073. PMC 4570937. PMID 26378135.

- ^ Morini L, Bernini M, Vezzoli S, Restori M, Moretti M, Crenna S, et al. (October 2017). "Death after 25C-NBOMe and 25H-NBOMe consumption". Forensic Science International. 279: e1–e6. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2017.08.028. PMID 28893436.

- ^ Byard RW, Cox M, Stockham P (November 2016). "Blunt Craniofacial Trauma as a Manifestation of Excited Delirium Caused by New Psychoactive Substances". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 61 (6): 1546–1548. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.13212. PMID 27723094. S2CID 4734566.

- ^ a b Sabastian LP, Christoffer B, Martin H, Martin AC, Jan K, Jesper LK (February 14, 2014). "Correlating the Metabolic Stability of Psychedelic 5-HT2A Agonists with Anecdotal Reports of Human Oral Bioavailability". Neurochemical Research. 39 (10): 2018–2023. doi:10.1007/s11064-014-1253-y. PMID 24519542. S2CID 254857910.

- ^ Adam H (January 18, 2017). "Pharmacology and Toxicology of N-Benzylphenethylamine ("NBOMe") Hallucinogens". Neuropharmacology of New Psychoactive Substances. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Vol. 32. Springer. pp. 283–311. doi:10.1007/7854_2016_64. ISBN 978-3-319-52444-3. PMID 28097528.

- ^ Boris D, Cristian C, Marcelo K, Edwar F, Bruce KC (August 2016). "Analysis of 25 C NBOMe in Seized Blotters by HPTLC and GC–MS". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 54 (7): 1153–1158. doi:10.1093/chromsci/bmw095. PMC 4941995. PMID 27406128.

- ^ Francesco SB, Ornella C, Gabriella A, Giuseppe V, Rita S, Flaminia BP, Eduardo C, Pierluigi S, Giovanni M, Guiseppe B, Fabrizio S (July 3, 2014). "25C-NBOMe: preliminary data on pharmacology, psychoactive effects, and toxicity of a new potent and dangerous hallucinogenic drug". BioMed Research International. 2014: 734749. doi:10.1155/2014/734749. PMC 4106087. PMID 25105138.

- ^ Adam JP, Simon HT, Simon LH (September 2021). "Pharmacology and toxicology of N-Benzyl-phenylethylamines (25X-NBOMe) hallucinogens". Novel Psychoactive Substances: Classification, Pharmacology and Toxicology (2 ed.). Academic Press. pp. 279–300. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-818788-3.00008-5. ISBN 978-0-12-818788-3. S2CID 240583877.

- ^ Rothman RB, Baumann MH, Savage JE, Rauser L, McBride A, Hufeisen SJ, Roth BL (December 2000). "Evidence for possible involvement of 5-HT(2B) receptors in the cardiac valvulopathy associated with fenfluramine and other serotonergic medications". Circulation. 102 (23): 2836–41. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.102.23.2836. PMID 11104741.

- ^ Fitzgerald LW, Burn TC, Brown BS, Patterson JP, Corjay MH, Valentine PA, Sun JH, Link JR, Abbaszade I, Hollis JM, Largent BL, Hartig PR, Hollis GF, Meunier PC, Robichaud AJ, Robertson DW (January 2000). "Possible role of valvular serotonin 5-HT(2B) receptors in the cardiopathy associated with fenfluramine". Molecular Pharmacology. 57 (1): 75–81. PMID 10617681.

- ^ Roth BL (January 2007). "Drugs and valvular heart disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (1): 6–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068265. PMID 17202450.

- ^ Xu P, Qiu Q, Li H, Yan S, Yang M, Naman CB, et al. (February 26, 2019). "25C-NBOMe, a Novel Designer Psychedelic, Induces Neurotoxicity 50 Times More Potent Than Methamphetamine In Vitro". Neurotoxicity Research. 35 (4): 993–998. doi:10.1007/s12640-019-0012-x. PMID 30806983. S2CID 255763701.

- ^ Álvarez-Alarcón N, Osorio-Méndez JJ, Ayala-Fajardo A, Garzón-Méndez WF, Garavito-Aguilar ZV (2021). "Zebrafish and Artemia salina in vivo evaluation of the recreational 25C-NBOMe drug demonstrates its high toxicity". Toxicology Reports. 8: 315–323. doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2021.01.010. ISSN 2214-7500. PMC 7868744. PMID 33598409.

- ^ "Explore N-(2C-B)-Fentanyl | PiHKAL · info". isomerdesign.com.

- ^ "Explore N-(2C-FLY)-Fentanyl | PiHKAL · info". isomerdesign.com.

- ^ Glennon, Richard A.; Bondarev, Mikhail L.; Khorana, Nantaka; Young, Richard; May, Jesse A.; Hellberg, Mark R.; McLaughlin, Marsha A.; Sharif, Najam A. (November 2004). "β-Oxygenated Analogues of the 5-HT2ASerotonin Receptor Agonist 1-(4-Bromo-2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-aminopropane". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 47 (24): 6034–6041. doi:10.1021/jm040082s. ISSN 0022-2623. PMID 15537358.

- ^ Beta-hydroxyphenylalkylamines and their use for treating glaucoma

- ^ "Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations (Part J — 2C-phenethylamines)". Canada Gazette. Vol. 150, no. 9. May 4, 2016. Archived from the original on August 31, 2016.

- ^ "Постановление Правительства РФ от 30.06.1998 N 681 "Об утверждении перечня наркотических средств, психотропных веществ и их прекурсоров, подлежащих контролю в Российской Федерации" (с изменениями и дополнениями)". base.garant.ru.

- ^ "Föreskrifter om ändring i Läkemedelsverkets föreskrifter (LVFS 2011:10) om förteckningar över narkotika;" (PDF). lakemedelsverket.se (in Swedish). Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Ketamine etc.) (Amendment) Order 2014". UK Statutory Instruments 2014 No. 1106. www.legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ "2016 - Final Rule: Placement of Three Synthetic Phenethylamines Into Schedule I". www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ "关于印发《非药用类麻醉药品和精神药品列管办法》的通知" (in Chinese). China Food and Drug Administration. September 27, 2015. Archived from the original on October 1, 2015. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- ^ "Látky, o které byl doplněn seznam č. 4 psychotropních látek (příloha č. 4 k nařízení vlády č. 463/2013 Sb.)" (PDF) (in Czech). Ministerstvo zdravotnictví. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- CS1 Brazilian Portuguese-language sources (pt-br)

- CS1 German-language sources (de)

- CS1 Swedish-language sources (sv)

- CS1 Chinese-language sources (zh)

- CS1 Czech-language sources (cs)

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Use mdy dates from August 2015

- Articles needing additional references from December 2022

- All articles needing additional references

- Articles with changed CASNo identifier

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Citation overkill

- Articles tagged with the inline citation overkill template from December 2022

- All articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from December 2022

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2012

- Articles with excerpts

- 2C (psychedelics)

- Designer drugs

- Bromobenzene derivatives

- PET radiotracers