Salbutamol

| |

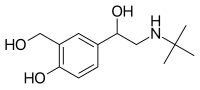

Salbutamol (top), (R)-(−)-salbutamol (center) and (S)-(+)-salbutamol (bottom) | |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Ventolin, Proventil, ProAir, others[1] |

| Other names | Albuterol (USAN US) |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Beta2-adrenergic agonist |

| Main uses | Asthma attacks[2] |

| Side effects | Headache, tremor, fast heart rate[2] |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | By mouth, inhalational, IV |

| Onset of action | <15 min (inhaled), <30 min (pill)[5] |

| Duration of action | 2–6 hrs[5] |

| Defined daily dose | 12 mg (by mouth or injection)[6] 0.8 to 10 mg (by inhalation)[7] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607004 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 3.8–6 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C13H21NO3 |

| Molar mass | 239.315 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

Salbutamol, also known as albuterol and marketed as Ventolin among other brand names,[1] is a medication that opens up the medium and large airways in the lungs.[5] It is used to treat asthma, including asthma attacks, exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).[5] It may also be used to treat high blood potassium levels.[10] Salbutamol is usually used with an inhaler or nebulizer, but it is also available in a pill, liquid, and intravenous solution.[5][11] Onset of action of the inhaled version is typically within 15 minutes and lasts for two to six hours.[5]

Common side effects include shakiness, headache, fast heart rate, dizziness, and feeling anxious.[5] Serious side effects may include worsening bronchospasm, irregular heartbeat, and low blood potassium levels.[5] It can be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding, but safety is not entirely clear.[5][12] It is a short-acting β2 adrenergic receptor agonist which works by causing relaxation of airway smooth muscle.[5]

Salbutamol was patented in 1966 in Britain and became commercially available in the UK in 1969.[13][14] It was approved for medical use in the United States in 1982.[5] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[15] Salbutamol is available as a generic medication.[5] The wholesale cost in the developing world of an inhaler which contains 200 doses is between US$1.12 and US$2.64 as of 2014[update].[16] In the United States, it is between US$25 and US$50 for a typical month's supply.[17] In 2017, it was the tenth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 50 million prescriptions.[18][19]

Medical uses

Salbutamol is typically used to treat bronchospasm (due to any cause—allergic asthma or exercise-induced), as well as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[5] It is also one of the most common medicines used in rescue inhalers (short-term bronchodilators to alleviate asthma attacks).[20]

As a β2 agonist, salbutamol also has use in obstetrics. Intravenous salbutamol can be used as a tocolytic to relax the uterine smooth muscle to delay premature labor. While preferred over agents such as atosiban and ritodrine, its role has largely been replaced by the calcium channel blocker nifedipine, which is more effective and better tolerated.[21]

Salbutamol has been used to treat acute high blood potassium, as it stimulates potassium flow into cells, thus lowering the potassium in the blood.[10]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 12 mg by mouth or by injection,[6] 0.8 mg when inhaled as a powder or aerosol, and 10 mg when inhaled as a solution.[7] The amount used depends on the severity of the attack.[2] This can vary from 2 to 4 puffs, up to 10 puffs every 10 minutes.[2] In a nebuliser 2.5 to 5 mg can be given to those over the age of 5.[22] In those under 5 years old 2.5 mg is used.[22] This can be given every 20 to 30 minutes as needed.[22] It can also be given as an infusion to try to delay labor at a rate of 15 to 45 micrograms per minute for up to 48 hours.[23]

-

-

-

Ventolin 2 mg tablets made by GSK (Turkey)

Side effects

The most common side effects are fine tremor, anxiety, headache, muscle cramps, dry mouth, and palpitation.[24] Other symptoms may include tachycardia, arrhythmia, flushing of the skin, myocardial ischemia (rare), and disturbances of sleep and behaviour.[24] Rarely occurring, but of importance, are allergic reactions of paradoxical bronchospasms, urticaria (hives), angioedema, hypotension, and collapse. High doses or prolonged use may cause hypokalemia, which is of concern especially in patients with kidney failure and those on certain diuretics and xanthine derivatives.[24]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

It can be used during pregnancy or breastfeeding.[2]

Pharmacology

The tertiary butyl group in salbutamol makes it more selective for β2 receptors,[26] which are the predominant receptors on the bronchial smooth muscles.

Activation of these receptors causes adenylyl cyclase to convert ATP to cAMP, beginning the signalling cascade that ends with the inhibition of myosin phosphorylation and lowering the intracellular concentration of calcium ions (myosin phosphorylation and calcium ions are necessary for muscle contractions). The increase in cAMP also inhibits inflammatory cells in the airway, such as basophils, eosinophils, and most especially mast cells, from releasing inflammatory mediators and cytokines.[27][28]

Salbutamol and other β2 receptor agonists also increase the conductance of channels sensitive to calcium and potassium ions, leading to hyperpolarization and relaxation of bronchial smooth muscles.[29]

Salbutamol is either filtered out by the kidneys directly or is first metabolized into 4'-O-sulfate, which is excreted in the urine.[11]

Structure and activity

Salbutamol is sold as a racemic mixture. The (R)-(−)-enantiomer (CIP nomenclature) is shown in the image at right (top), and is responsible for the pharmacologic activity; the (S)-(+)-enantiomer (bottom) blocks metabolic pathways associated with elimination of itself and of the pharmacologically active enantiomer (R).[30]

The slower metabolism of the (S)-(+)-enantiomer also causes it to accumulate in the lungs, which can cause airway hyperreactivity and inflammation.[31]

Potential formulation of the R form as an enantiopure drug is complicated by the fact that the stereochemistry is not stable, but rather the compound undergoes racemization within a few days to weeks, depending on pH.[32]

History

Salbutamol was discovered in 1966, by a team led by David Jack at the Allen and Hanburys laboratory (a subsidiary of Glaxo) in Ware, Hertfordshire, England, and was launched as Ventolin in 1969.[33]

The 1972 Munich Olympics were the first Olympics where anti-doping measures were deployed, and at that time beta-2 agonists were considered to be stimulants with high risk of abuse for doping. Inhaled salbutamol was banned from those games, but by 1986 was permitted (although oral beta-2 agonists were not). After a steep rise in the number of athletes taking beta-2 agonists for asthma in the 1990s, Olympic athletes were required to provide proof that they had asthma in order be allowed to use inhaled beta-2 agonists.[34]

In February 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first generic of albuterol sulfate (Albuterol Sulfate Inhalation Aerosol) for the treatment or prevention of bronchospasm in people four years of age and older with reversible obstructive airway disease and the prevention of exercise-induced bronchospasm in people four years of age and older.[35][36] The FDA granted approval of the generic albuterol sulfate inhalation aerosol to Perrigo Pharmaceutical Co.[35]

In April 2020, The FDA approved the first generic of Proventil HFA (albuterol sulfate) Metered Dose Inhaler, 90 mcg/Inhalation, for the treatment or prevention of bronchospasm in patients four years of age and older who have reversible obstructive airway disease, as well as the prevention of exercise-induced bronchospasm in this age group.[37] The FDA granted approval of this generic albuterol sulfate inhalation aerosol to Cipla Limited.[37]

Society and culture

Cost

The wholesale cost of a 200-dose inhaler is between US$1.12 and US$2.64 in the developing world as of 2014[update][16] and to the NHS in the United Kingdom is GB£3.31 as of 2020[update].[38] In the United States, a typical month's supply is between $25 and $50 as of 2015.[17] In 2020, generic versions were approved in the United States.[35][37]In 2017, it was the tenth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 50 million prescriptions.[18][19]

-

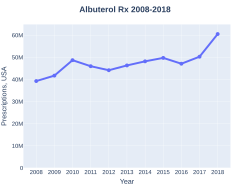

Albuterol costs (USA)

-

Albuterol prescriptions (USA)

Names

Salbutamol is the international nonproprietary name (INN) while albuterol is the United States Adopted Name (USAN).[39] The drug is usually manufactured and distributed as the sulfate salt (salbutamol sulfate).

It was first sold by Allen & Hanburys (UK) under the brand name Ventolin, and has been used for the treatment of asthma ever since.[40] The drug is marketed under many names worldwide.[1]

Doping

As of 2011[update] there was no evidence that an increase in physical performance occurs after inhaling salbutamol, but there are various reports for benefit when delivered orally or intravenously.[41][42] In spite of this, salbutamol required "a declaration of Use in accordance with the International Standard for Therapeutic Use Exemptions" under the 2010 WADA prohibited list. This requirement was relaxed when the 2011 list was published to permit the use of "salbutamol (maximum 1600 micrograms over 24 hours) and salmeterol when taken by inhalation in accordance with the manufacturers' recommended therapeutic regimen."[43][44]

Abuse of the drug may be confirmed by detection of its presence in plasma or urine, typically exceeding 1000 ng/mL. The window of detection for urine testing is on the order of just 24 hours, given the relatively short elimination half-life of the drug,[45][46][47] estimated at between 5 and 6 hours following oral administration of 4 mg.[27]

Environmental effects

As the salbutamol MDI releases green house gases there are recommendations to switch to dry powder inhalers or soft mist inhalers such as terbutaline turbohaler.[48]

Research

Salbutamol has been studied in subtypes of congenital myasthenic syndrome associated with mutations in Dok-7.[49]

It has also been tested in a trial aimed at treatment of spinal muscular atrophy; it is speculated to modulate the alternative splicing of the SMN2 gene, increasing the amount of the SMN protein whose deficiency is regarded as a cause of the disease.[50][51]

Veterinary use

Salbutamol's low toxicity makes it safe for other animals and thus is the medication of choice for treating acute airway obstruction in most species.[31] It is usually used to treat bronchospasm or coughs in cats and dogs and used as a bronchodilator in horses with recurrent airway obstruction; it can also be used in emergencies to treat asthmatic cats.[52][53]

Toxic effects require an extremely high dose, and most overdoses are due to dogs chewing on and puncturing an inhaler or nebulizer vial.[54]

See also

- Ipratropium/salbutamol

- Isoprenaline

- Levosalbutamol – the (R)-(−)-enantiomer

- Salmeterol

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Salbutamol". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-30. Retrieved April 11, 2016.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Thereaputic Goods Administration (2018-12-19). "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2017-06-20.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Albuterol Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 8 March 2019. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 "Albuterol". Drugs.com. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved Dec 2, 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ↑ Thereaputic Goods Administration. "Poisons Standard October 2017". Australian Government. Archived from the original on 2018-01-11. Retrieved 2018-01-11.

- ↑ "Prescription Drug List". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2017-06-20.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Mahoney BA, Smith WA, Lo DS, Tsoi K, Tonelli M, Clase CM (April 2005). "Emergency interventions for hyperkalaemia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003235. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003235.pub2. PMC 6457842. PMID 15846652.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Starkey ES, Mulla H, Sammons HM, Pandya HC (September 2014). "Intravenous salbutamol for childhood asthma: evidence-based medicine?" (PDF). Archives of Disease in Childhood. 99 (9): 873–7. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-304467. PMID 24938536. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Yaffe, Sumner J. (2011). Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: a reference guide to fetal and neonatal risk (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 32. ISBN 9781608317080. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Landau, Ralph (1999). Pharmaceutical innovation: revolutionizing human health. Philadelphia: Chemical Heritage Press. p. 226. ISBN 9780941901215. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 542. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Salbutamol". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 448. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Albuterol - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. 1 December 1981. Archived from the original on 6 November 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ Hatfield, Heather. "Asthma: The Rescue Inhaler -- Now a Cornerstone of Asthma Treatment". WebMD. Archived from the original on 2017-07-16. Retrieved 2017-06-27.

- ↑ Rossi S (2004). Australian Medicines Handbook. AMH. ISBN 978-0-9578521-4-3.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "SALBUTAMOL = ALBUTEROL nebuliser solution - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ↑ "SALBUTAMOL = ALBUTEROL injectable - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "3.1.1.1 Selective beta2 agonists – side effects". British National Formulary (57 ed.). London: BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and Royal Pharmaceutical Society Publishing. March 2008. ISBN 978-0-85369-778-7.

- ↑ Marques, Lara; Vale, Nuno (March 2023). "Unraveling the Impact of Salbutamol Polytherapy: Clinically Relevant Drug Interactions". Future Pharmacology. 3 (1): 296–316. doi:10.3390/futurepharmacol3010019. ISSN 2673-9879.

- ↑ Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito SW (2013). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1314–1320. ISBN 9781609133450. OCLC 748675182. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Albuterol Sulfate". Rx List: The Internet Drug Index. Archived from the original on 2014-07-18. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- ↑ Papich, Mark G. (2007). "Albuterol Sulfate". Saunders Handbook of Veterinary Drugs (2nd ed.). St. Louis, Mo: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9781416028888.

- ↑ US Department of Health and Human Services (2017-04-28). "Albuterol - Medical Countermeasures Database". CHEMM. Archived from the original on 2017-08-03. Retrieved 2017-06-23.

- ↑ Mehta, Akul. "Medicinal Chemistry of the Peripheral Nervous System – Adrenergics and Cholinergics their Biosynthesis, Metabolism, and Structure Activity Relationships". Archived from the original on 2010-11-04. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Inhalation Therapy of Airway Disease". Merck Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on 2017-06-25. Retrieved 2017-06-22.

- ↑ Liu Q, Li Q, Han T, Hu T, Zhang X, Hu J, Hu H, Tan W (September 1, 2017). "Study of pH Stability of R-Salbutamol Sulfate Aerosol Solution and Its Antiasthmatic Effects in Guinea Pigs". Biol Pharm Bull. 40 (9): 1374–1380. doi:10.1248/bpb.b17-00067. PMID 28652557.

- ↑ "Sir David Jack, who has died aged 87, was the scientific brain behind the rise of the pharmaceuticals company Glaxo". The Telegraph. Nov 17, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-11-25.

- ↑ Fitch KD (2006). "beta2-Agonists at the Olympic Games". Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 31 (2–3): 259–68. doi:10.1385/CRIAI:31:2:259. PMID 17085798.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 "FDA approves first generic of ProAir HFA". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 24 February 2020. Archived from the original on 25 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Albuterol Sulfate: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 "FDA Approves First Generic of a Commonly Used Albuterol Inhaler to Treat and Prevent Bronchospasm". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 8 April 2020. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 267-269. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ "Salbutamol". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-09-03. Retrieved 2020-02-18.

- ↑ "Ventolin remains a breath of fresh air for asthma sufferers, after 40 years" (PDF). The Pharmaceutical Journal. 279 (7473): 404–405. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 15, 2007.

- ↑ Pluim BM, de Hon O, Staal JB, Limpens J, Kuipers H, Overbeek SE, et al. (January 2011). "β₂-Agonists and physical performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Sports Medicine. 41 (1): 39–57. doi:10.2165/11537540-000000000-00000. PMID 21142283.

- ↑ Davis E, Loiacono R, Summers RJ (June 2008). "The rush to adrenaline: drugs in sport acting on the beta-adrenergic system". British Journal of Pharmacology. 154 (3): 584–97. doi:10.1038/bjp.2008.164. PMC 2439523. PMID 18500380.

- ↑ "The 2010 Prohibited List International Standard" (PDF). WADA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2010-10-20.

- ↑ "The 2011 Prohibited List International Standard" (PDF). WADA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-05-13. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- ↑ Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Biomedical Publications. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-0-9626523-6-3.

- ↑ Bergés R, Segura J, Ventura R, Fitch KD, Morton AR, Farré M, et al. (September 2000). "Discrimination of prohibited oral use of salbutamol from authorized inhaled asthma treatment". Clinical Chemistry. 46 (9): 1365–75. doi:10.1093/clinchem/46.9.1365. PMID 10973867. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17.

- ↑ Schweizer C, Saugy M, Kamber M (September 2004). "Doping test reveals high concentrations of salbutamol in a Swiss track and field athlete". Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine. 14 (5): 312–5. doi:10.1097/00042752-200409000-00018. PMID 15377972.

- ↑ CASCADES - Primary Care Toolkit_EN - Page 28. 2023. p. 28. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ↑ Liewluck T, Selcen D, Engel AG (November 2011). "Beneficial effects of albuterol in congenital endplate acetylcholinesterase deficiency and Dok-7 myasthenia". Muscle & Nerve. 44 (5): 789–94. doi:10.1002/mus.22176. PMC 3196786. PMID 21952943. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Van Meerbeke JP, Sumner CJ (October 2011). "Progress and promise: the current status of spinal muscular atrophy therapeutics". Discovery Medicine. 12 (65): 291–305. PMID 22031667. Archived from the original on 2015-05-12. Retrieved 2015-08-27.

- ↑ Lewelt A, Newcomb TM, Swoboda KJ (February 2012). "New therapeutic approaches to spinal muscular atrophy". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 12 (1): 42–53. doi:10.1007/s11910-011-0240-9. PMC 3260050. PMID 22134788.

- ↑ Plumb, Donald C. (2011). "Albuterol Sulfate". Plumb's Veterinary Drug Handbook (7th ed.). Stockholm, Wisconsin; Ames, Iowa: Wiley. pp. 24–25. ISBN 9780470959640.

- ↑ Clarke, Kathy W.; Trim, Cynthia M. (2013-06-28). Veterinary Anaesthesia E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 612. ISBN 9780702054235. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Cote, Etienne (2014-12-09). "Albuterol Toxicosis". Clinical Veterinary Advisor - E-Book: Dogs and Cats. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 45–46. ISBN 9780323240741. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

External links

- "Albuterol". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2019-12-21. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- Salbutamol Archived 2018-02-01 at the Wayback Machine at The Periodic Table of Videos

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- Wikipedia articles incorporating the PD-notice template

- CS1 maint: date format

- Use British English from June 2017

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Infobox drug with local INN variant

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2014

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2020

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2011

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with changed DrugBank identifier

- Antiasthmatic drugs

- Beta-adrenergic agonists

- Chemical substances for emergency medicine

- GlaxoSmithKline brands

- Merck & Co. brands

- Phenols

- Phenylethanolamines

- Racemate

- Sympathomimetic amines

- Tert-butyl compounds

- World Health Organization essential medicines

- RTT