Cyproheptadine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (/ˌsaɪproʊˈhɛptədiːn/[1] |

| Trade names | Periactin, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | First-generation antihistamine[2][3] |

| Main uses | Allergies[2][3] |

| Side effects | Sleepiness, dizziness, agitation, poor coordination[2] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682541 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Protein binding | 96 to 99% |

| Metabolism | Liver[4][5] Mostly CYP3A4 mediated. |

| Elimination half-life | 8.6 hours[6] |

| Excretion | Faecal (2-20%; 34% of this as unchanged drug) and renal (40%; none as unchanged drug)[4][5] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C21H21N |

| Molar mass | 287.406 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Cyproheptadine, sold under the brand name Periactin among others, is a first-generation antihistamine primarily used to treat allergies.[2][3] This may include itchiness, hay fever, and hives.[3] It may also be used for serotonin syndrome.[7] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include sleepiness, dizziness, agitation, and poor coordination.[2] Other side effects may include swelling, problems urinating, and increased weight.[3] There is no evidence of harm with use during pregnancy, however such use has not been well studied.[8] Care should be taken in those at risk of glaucoma.[3]

Cyproheptadine was patented in 1959 and came into medical use in 1961.[9] It is available as a generic medication.[10] In the United Kingdom 30 tablets of 4 mg costs the NHS about 6 pounds in 2020.[3] This amount in the United States costs about 10 USD.[10]

Medical uses

Cyproheptadine is used to treat allergic reactions (specifically hay fever).[11] While effective for this purpose, second generation antihistamines such as ketotifen and loratadine have shown equal results with fewer side effects.[12]

It is also used to prevent migraines. A 2013 study found a reduced rate within 7 to 10 days. The average frequency before use was 8.7 times per month, this was decreased to 3.1 times per month at 3 months after the start of treatment.[12][13] This use is on the label in the UK and some other countries.

Other uses

It has been used for cyclical vomiting syndrome in infants; the only evidence for this use comes from retrospective studies.[14]

Cyproheptadine is sometimes used off-label to improve akathisia in people on antipsychotic medications.[15]

It used off-label to treat various dermatological conditions, including psychogenic itch[16] drug-induced hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating),[17] and prevention of blister formation for some people with epidermolysis bullosa simplex.[18]

One of the effects of the drug is increased appetite and weight gain, which has led to its use (off-label in the USA) for this purpose in children who are wasting as well as people with cystic fibrosis.[19][20][21]

It is also used off-label in the management of moderate to severe cases of serotonin syndrome, a complex of symptoms associated with the use of serotonergic drugs, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (and monoamine oxidase inhibitors), and in cases of high levels of serotonin in the blood resulting from a serotonin-producing carcinoid tumor.[22][23]

Dosage

The typical dose is 4 mg three times per day in adults.[3]

Side effects

- Sedation and sleepiness (often transient)

- Dizziness

- Disturbed coordination

- Confusion

- Restlessness

- Excitation

- Nervousness

- Tremor

- Irritability

- Insomnia

- Paresthesias

- Neuritis

- Convulsions

- Euphoria

- Hallucinations

- Hysteria

- Faintness

- Allergic manifestation of rash and edema

- Diaphoresis

- Urticaria

- Photosensitivity

- Acute labyrinthitis

- Diplopia (seeing double)

- Vertigo

- Tinnitus

- Hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Palpitation

- Extrasystoles

- Anaphylactic shock

- Hemolytic anemia

- Blood dyscrasias such as leukopenia, agranulocytosis and thrombocytopenia

- Cholestasis

- Liver effects such as:

- - Hepatitis

- - Jaundice

- - Hepatic failure[24]

- - Hepatic function abnormality

- Epigastric distress

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Anticholinergic side effects such as:

- - Blurred vision

- - Constipation

- - Xerostomia (dry mouth)

- - Tachycardia (high heart rate)

- - Urinary retention

- - Difficulty passing urine

- - Nasal congestion

- - Nasal or throat dryness

- Urinary frequency

- Early menses

- Thickening of bronchial secretions

- Tightness of chest and wheezing

- Fatigue

- Chills

- Headache

- Increased appetite

- Weight gain

Overdose

Gastric decontamination measures such as activated charcoal are sometimes recommended in cases of overdose. The symptoms are usually indicative of CNS depression (or conversely CNS stimulation in some) and excess anticholinergic side effects. The LD50 in mice is 123 mg/kg and 295 mg/kg in rats.[4][5]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Action | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | 0.06 | ↓ | Human | |

| H2 | ND | ND | ||

| H3 | >10,000 | Human | ||

| H4 | 202 | Human | ||

| M1 | 12 | ↓ | Human | |

| M2 | 7 | ↓ | Human | |

| M3 | 12 | ↓ | Human | |

| M4 | 8 | ↓ | Human | |

| M5 | 11.8 | ↓ | Human | |

| 5-HT1A | 59 | Human | ||

| 5-HT2A | 1.67 | ↓ | Human | |

| 5-HT2B | 1.54 | ↓ | Human | |

| 5-HT2C | 2.23 | ↓ | Human | |

| 5-HT3 | 228 | Mouse | ||

| 5-HT6 | 142 | Human | ||

| 5-HT7 | 123 | Human | ||

| D1 | 117 | Human | ||

| D2 | 112 | ↓ | Human | |

| D3 | 8 | Human | ||

| SERT | 4,100 | Rat | ||

| NET | 290 | Rat | ||

| DAT | ND | ND | ||

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. The ↓ and ↑ indicate antagonist and agonist type actions respectively. | ||||

Cyproheptadine is a very potent antihistamine or antagonist of the H1 receptor. At higher concentrations, it also has anticholinergic, antiserotonergic, and antidopaminergic activities. Of the serotonin receptors, it is an especially potent antagonist of the 5-HT2 receptors, and this underlies its effectiveness in the treatment of serotonin syndrome.

Cyproheptadine is known to be an antagonist or inverse agonist of all of the receptors listed in the adjacent table.[25]

Cyproheptadine has weak antiandrogenic activity.[26]

Pharmacokinetics

Cyproheptadine is well-absorbed following oral ingestion, with peak plasma levels occurring after 1 to 3 hours.[27] Its terminal half-life when taken orally is approximately 8 hours.[6]

Chemistry

Cyproheptadine is a tricyclic benzocycloheptene and is closely related to pizotifen and ketotifen as well as to tricyclic antidepressants.

Research

Cyproheptadine was studied in one small trial as an adjunct in people with schizophrenia whose condition was stable and were on other medication; while attention and verbal fluency appeared to be improved, the study was too small to draw generalizations from.[28] It has also been studied as an adjuvant in two other trials in people with schizophrenia, around fifty people overall, and did not appear to have an effect.[29]

There have been some trials to see if cyproheptadine could reduce sexual dysfunction caused by SSRI and antipsychotic medications.[30]

Cyproheptadine has been studied for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder.[29]

Veterinary use

Cyproheptadine is used in cats as an appetite stimulant[31] and as an adjunct in the treatment of asthma.[32] Possible adverse effects include excitement and aggressive behavior.[33] The elimination half-life of cyproheptadine in cats is 12 hours.[32]

Cyproheptadine is a second line treatment for pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction in horses.[34][35]

Society and culture

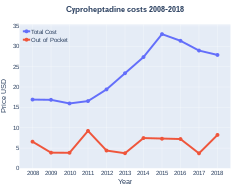

Cost

In the United Kingdom 30 tablets of 4 mg costs the NHS about 6 pounds in 2020.[3] This amount in the United States costs about 10 USD.[10]

-

Costs (US)

-

Cyproheptadine prescriptions (US)

References

- ↑ "Cyproheptadine". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "Cyproheptadine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 BNF 79. London: Pharmaceutical Press. March 2020. p. 292. ISBN 978-0857113658.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "CYPROHEPTADINE HYDROCHLORIDE tablet [Boscogen, Inc.]" (PDF). DailyMed. Boscogen, Inc. November 2010. Archived from the original on 4 July 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 "PRODUCT INFORMATION PERIACTIN® (cyproheptadine hydrochloride)" (PDF). Aspen Pharmacare Australia. Aspen Pharmacare Australia Pty Ltd. 17 November 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Gunja N, Collins M, Graudins A (2004). "A comparison of the pharmacokinetics of oral and sublingual cyproheptadine". Journal of Toxicology. Clinical Toxicology. 42 (1): 79–83. doi:10.1081/clt-120028749. PMID 15083941. S2CID 20196551.

- ↑ Boyer EW, Shannon M (March 2005). "The serotonin syndrome" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–20. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-06-18.

- ↑ "Cyproheptadine (Periactin) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 547. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Cyproheptadine". Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- ↑ "MedlinePlus Drug Information: Cyproheptadine". Archived from the original on 2008-10-01. Retrieved 2018-03-21.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 De Bruyne, P; Christiaens, T; Boussery, K; Mehuys, E; Van Winckel, M (January 2017). "Are antihistamines effective in children? A review of the evidence". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 102 (1): 56–60. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-310416. PMID 27335428. S2CID 21185048.

- ↑ Saito, Y; Yamanaka, G; Shimomura, H; Shiraishi, K; Nakazawa, T; Kato, F; Shimizu-Motohashi, Y; Sasaki, M; Maegaki, Y (May 2017). "Reconsideration of the diagnosis and treatment of childhood migraine: A practical review of clinical experiences". Brain & Development. 39 (5): 386–394. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2016.11.011. PMID 27993427. S2CID 34703034.

- ↑ Salvatore, S; Barberi, S; Borrelli, O; Castellazzi, A; Di Mauro, D; Di Mauro, G; Doria, M; Francavilla, R; Landi, M; Martelli, A; Miniello, VL; Simeone, G; Verduci, E; Verga, C; Zanetti, MA; Staiano, A; SIPPS Working Group on, FGIDs. (16 July 2016). "Pharmacological interventions on early functional gastrointestinal disorders". Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 42 (1): 68. doi:10.1186/s13052-016-0272-5. PMC 4947301. PMID 27423188.

- ↑ Taylor, David; Paton, Carol; Kapur, Shitij (2015). The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 85. ISBN 9781118754573. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ↑ Szepietowski, JC; Reszke, R (2016). Psychogenic Itch Management. Current Problems in Dermatology. Vol. 50. pp. 124–32. doi:10.1159/000446055. ISBN 978-3-318-05888-8. PMID 27578081.

- ↑ Ashton AK, Weinstein WL (May 2002). "Cyproheptadine for drug-induced sweating". American Journal of Psychiatry. 159 (5): 874–5. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.874-a. PMID 11986151. Archived from the original on 2012-03-19. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ↑ Pfendner, Ellen G.; Bruckner, Anna L. (October 13, 2016). "Epidermolysis Bullosa Simplex". GeneReviews. PMID 20301543. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Ciproheptadina, estimulante del apetito (Cyproheptadine, appetite stimulant)". Archived from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ↑ "Bioplex NF". Archived from the original on 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ↑ Harrison ME, Norris ML, Robinson A, Spettigue W, Morrissey M, Isserlin L (2019). "Use of cyproheptadine to stimulate appetite and body weight gain: A systematic review". Appetite. 137: 62–72. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2019.02.012. PMID 30825493. S2CID 72333631.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ Iqbal, MM; Basil, MJ; Kaplan, J; Iqbal, MT (November 2012). "Overview of serotonin syndrome". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 24 (4): 310–8. PMID 23145389.

- ↑ Chertoff, Jason (8 July 2014). "Cyproheptadine-Induced Acute Liver Failure". ACG Case Reports Journal. 1 (4): 212–213. doi:10.14309/crj.2014.56. PMC 4286888. PMID 25580444.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ↑ Pucci E, Petraglia F (December 1997). "Treatment of androgen excess in females: yesterday, today and tomorrow". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 11 (6): 411–33. doi:10.3109/09513599709152569. PMID 9476091.

- ↑ Lindsay Murray; Frank Daly; David McCoubrie; Mike Cadogan (15 January 2011). Toxicology Handbook. Elsevier Australia. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-7295-3939-5. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ↑ Buoli, M; Altamura, AC (March 2015). "May non-antipsychotic drugs improve cognition of schizophrenia patients?". Pharmacopsychiatry. 48 (2): 41–50. doi:10.1055/s-0034-1396801. PMID 25584772.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Dabaghzadeh, F; Khalili, H; Ghaeli, P; Dashti-Khavidaki, S (December 2012). "Potential benefits of cyproheptadine in HIV-positive patients under treatment with antiretroviral drugs including efavirenz". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 13 (18): 2613–24. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.742887. PMID 23140169. S2CID 25769557.

- ↑ Nunes, LV; Moreira, HC; Razzouk, D; Nunes, SO; Mari Jde, J (2012). "Strategies for the treatment of antipsychotic-induced sexual dysfunction and/or hyperprolactinemia among patients of the schizophrenia spectrum: a review". Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 38 (3): 281–301. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2011.606883. PMID 22533871. S2CID 23406005.

- ↑ Agnew, W; Korman, R (September 2014). "Pharmacological appetite stimulation: rational choices in the inappetent cat". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 16 (9): 749–56. doi:10.1177/1098612X14545273. PMID 25146662. S2CID 37126352.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Dowling PM (February 8, 2005). "Systemic Therapy of Airway Disease: Cyproheptadine". In Kahn CM, Line S, Aiello SE (eds.). The Merck Veterinary Manual (9th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-911910-50-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|archive-url=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (help) Retrieved on October 26, 2008. - ↑ Dowling PM (February 8, 2005). "Drugs Affecting Appetite". In Kahn CM, Line S, Aiello SE (eds.). The Merck Veterinary Manual (9th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-911910-50-6.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|archive-url=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (help) Retrieved on October 26, 2008. - ↑ Durham, AE (April 2017). "Therapeutics for Equine Endocrine Disorders". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Equine Practice. 33 (1): 127–139. doi:10.1016/j.cveq.2016.11.003. PMID 28190613.

- ↑ Merck Vet Manual. "Hirsutism Associated with Adenomas of the Pars Intermedia". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: uses authors parameter

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: access-date without URL

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Antiandrogens

- Antihistamines

- Antipsychotics

- Appetite stimulants

- Dibenzocycloheptenes

- Dopamine antagonists

- Local anesthetics

- Muscarinic antagonists

- Piperidines

- Serotonin antagonists

- Sodium channel blockers

- RTT