Sertraline

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈsərtrəˌliːn/ |

| Trade names | Zoloft and others[1] |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| Main uses | Major depression, PTSD[2] |

| Addiction risk | None[5] |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | By mouth (tablets and solution) |

| Defined daily dose | 50 mg[4] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697048 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 44% |

| Protein binding | 98.5% |

| Metabolism | Liver (N-demethylation mainly by CYP2B6)[6] |

| Metabolites | Norsertraline |

| Elimination half-life | ~23–26 h (66 h [less-active[7] metabolite, norsertraline])[8][9][10][11] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

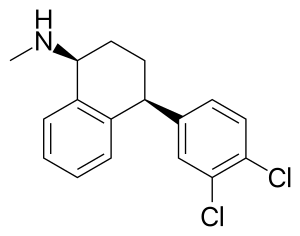

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H17Cl2N |

| Molar mass | 306.23 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Sertraline, sold under the brand name Zoloft among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class.[12] It is used to treat major depressive disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, and social anxiety disorder.[12] Sertraline is taken by mouth.[12]

Common side effects include diarrhea, sexual dysfunction, and troubles with sleep.[12] Serious side effects include an increased risk of suicide in those less than 25 years old and serotonin syndrome.[12] It is unclear whether use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe.[13] It should not be used together with MAO inhibitor medication.[12] Sertraline is believed to work by increasing serotonin effects in the brain.[12]

Sertraline was approved for medical use in the United States in 1991 and initially sold by Pfizer.[12] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines as an alternative to fluoxetine.[14] It is available as a generic medication.[12] In the United States, the wholesale cost is about US$1.50 per month as of 2018.[15] In 2016, it was the most commonly prescribed psychiatric medication in the United States,[16] with over 37 million prescriptions.[17] In 2017, it was the 14th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States with over 38 million prescriptions.[18][17]

Medical uses

Sertraline is used for a number of conditions, including major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder (SAD).[12] It has also been used for premature ejaculation and vascular headaches but evidence of the effectiveness in treating those conditions is not robust.[12] Sertraline is not approved for use in children except for those with OCD.[19][20]

Depression

It is unclear if sertraline is any different from another SSRI, paroxetine, for depression; though escitalopram may have some benefits over sertraline.[21]

Evidence does not show a benefit in children with depression.[22]

With depression in dementia, there is no benefit compared to either placebo or mirtazapine.[23]

Comparison with other antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) as a group are considered to work better than SSRIs for melancholic depression[24] and in inpatients,[25] but not necessarily for simply more severe depression.[26] In line with this generalization, sertraline was no better than placebo in inpatients (see History) and as effective as the TCA clomipramine for severe depression.[27] The comparative efficacy of sertraline and TCAs for melancholic depression has not been studied. A 1998 review suggested that, due to its pharmacology, sertraline may be more efficacious than other SSRIs and equal to TCAs for the treatment of melancholic depression.[28]

A meta-analysis of 12 new-generation antidepressants showed that sertraline and escitalopram are the best in terms of efficacy and acceptability in the acute-phase treatment of adults with unipolar MDD. Reboxetine was significantly worse.[29]

Comparative clinical trials demonstrated that sertraline is similar in efficacy against depression to moclobemide,[30] nefazodone,[31] escitalopram, bupropion,[32] citalopram, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and mirtazapine.[33] There is low quality evidence that sertraline is more efficacious for the treatment of depression than fluoxetine.[34]

Elderly

Sertraline used for the treatment of depression in elderly (older than 60) patients was superior to placebo and comparable to another SSRI fluoxetine, and TCAs amitriptyline, nortriptyline (Pamelor) and imipramine. Sertraline had much lower rates of adverse effects than these TCAs, with the exception of nausea, which occurred more frequently with sertraline. In addition, sertraline appeared to be more effective than fluoxetine or nortriptyline in the older-than-70 subgroup.[35] A 2003 trial of sertraline in elderly people found a clinically very modest improvement in depression and no improvement in quality of life.[36]

A meta-analysis on SSRIs and SNRIs that look at partial response (defined as at least a 50% reduction in depression score from baseline) found that sertraline, paroxetine and duloxetine were better than placebo.[37]

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Sertraline is effective for the treatment of OCD in adults and children.[38] It was better tolerated and, based on intention-to-treat analysis, performed better than the gold standard of OCD treatment clomipramine.[39] It is generally accepted that the sertraline dosages necessary for the effective treatment of OCD are higher than the usual dosage for depression.[40] The onset of action is also slower for OCD than for depression.[41]

Cognitive behavioral therapy alone was superior to sertraline in both adults and children; however, the best results were achieved using a combination of these treatments.[42][43]

Panic disorder

Treatment of panic disorder with sertraline results in a decrease of the number of panic attacks and an improved quality of life.[44] In four double-blind studies sertraline was shown to be superior to placebo for the treatment of panic disorder. The response rate was independent of the dose. In addition to decreasing the frequency of panic attacks by about 80% (vs. 45% for placebo) and decreasing general anxiety, sertraline resulted in improvement of quality of life on most parameters. The patients rated as "improved" on sertraline reported better quality of life than the ones who "improved" on placebo. The authors of the study argued that the improvement achieved with sertraline is different and of a better quality than the improvement achieved with placebo.[44][45] Sertraline was equally effective for men and women.[45] While imprecise, comparison of the results of trials of sertraline with separate trials of other anti-panic agents (clomipramine, imipramine, clonazepam, alprazolam, fluvoxamine and paroxetine) indicates approximate equivalence of these medications.[44]

Other anxiety disorders

Sertraline is effective for the treatment of social phobia.[46] Improvement in scores on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale were found with sertraline but not with placebo.[47] In children, a combination of sertraline and cognitive behavioural therapy had a superior response rate to each intervention alone, and both sertraline and CBT were alone superior to placebo and not significantly different from one another.[48]

There is tentative evidence that sertraline, as well as other SSRI/SNRI antidepressants, can help with the symptoms of general anxiety disorder.[49] The trials have generally been short in length (6–12 weeks) and pharmacological treatments are associated with more frequent side effects.[49]

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

SSRIs, including sertraline, reduce the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome.[50] Side effects such as nausea are common.[50] Sertraline is effective in alleviating the symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), a severe form of premenstrual syndrome. Significant improvement was observed in 50–60% of cases treated with sertraline vs. 20–30% of cases on placebo. The improvement began during the first week of treatment, and in addition to mood, irritability, and anxiety, improvement was reflected in better family functioning, social activity and general quality of life. Work functioning and physical symptoms, such as swelling, bloating and breast tenderness, were less responsive to sertraline.[51][52] Taking sertraline only during the luteal phase, that is, the 12–14 days before menses, was shown to work as well as continuous treatment.[50]

Other uses

Sertraline when taken daily can be useful for the treatment of some aspects of premature ejaculation.[53] A disadvantage of SSRIs is that they require continuous daily treatment to delay ejaculation significantly,[54] and it is not clear how they affect psychological distress of those with the condition or the person's control over ejaculation timing.[55]

The benefit of sertraline in PTSD is not significant per the National Institute of Clinical Excellence.[56] Others, however, do feel that there is a benefit from its use.[57]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 50 mg.[4] The typical dose is 50 mg once per day which may be increased to 100 mg per day if not effective enough after 4 weeks.[2] For depression at least nine months of medication is recommended while for PSTD it should be taken until a few months after symptoms improved.[2] It should be stopped gradually over two to four weeks.[2] Smaller doses should be used in people with mild or moderate liver problems and it should not be used at all in those with severe liver problems.[2]

Side effects

Compared to other SSRIs, sertraline tends to be associated with a higher rate of psychiatric side effects and diarrhea.[58][59] It tends to be more activating (that is, associated with a higher rate of anxiety, agitation, insomnia, etc.) than other SSRIs, aside from fluoxetine.[60]

Over more than six months of sertraline therapy for depression, people showed a nonsignificant weight increase of 0.1%.[61] Similarly, a 30-month-long treatment with sertraline for OCD resulted in a mean weight gain of 1.5% (1 kg).[62] Although the difference did not reach statistical significance, the weight gain was lower for fluoxetine (1%) but higher for citalopram, fluvoxamine and paroxetine (2.5%). Of the sertraline group, 4.5% gained a large amount of weight (defined as more than 7% gain). This result compares favorably with placebo, where, according to the literature, 3–6% of patients gained more than 7% of their initial weight. The large weight gain was observed only among female members of the sertraline group; the significance of this finding is unclear because of the small size of the group.[62] The incidence of diarrhea is higher with sertraline—especially when prescribed at higher doses—in comparison to other SSRIs.[21]

Over a two-week treatment of healthy volunteers, sertraline slightly improved verbal fluency but did not affect word learning, short-term memory, vigilance, flicker fusion time, choice reaction time, memory span, or psychomotor coordination.[63][64] In spite of lower subjective rating, that is, feeling that they performed worse, no clinically relevant differences were observed in the objective cognitive performance in a group of people treated for depression with sertraline for 1.5 years as compared to healthy controls.[65] In children and adolescents taking sertraline for six weeks for anxiety disorders, 18 out of 20 measures of memory, attention and alertness stayed unchanged. Divided attention was improved and verbal memory under interference conditions decreased marginally. Because of the large number of measures taken, it is possible that these changes were still due to chance.[66] The unique effect of sertraline on dopaminergic neurotransmission may be related to these effects on cognition and vigilance.[67][68] Sertraline's effect on the dopaminergic system may explain the risk of oromandibular dystonia.[69][70]

Sexual

Like other SSRIs, sertraline is associated with sexual side effects, including sexual arousal disorder and difficulty achieving orgasm. The frequency of sexual side effects depends on whether they are reported by people spontaneously, as in the manufacturer's trials, or actively solicited by physicians. While nefazodone, bupropion, and reboxetine do not have negative effects on sexual functioning, 67% of men on sertraline experienced ejaculation difficulties versus 18% before the treatment.[71] Sexual arousal disorder, defined as "inadequate lubrication and swelling for women and erectile difficulties for men", occurred in 12% of people on sertraline as compared with 1% of patients on placebo. The mood improvement resulting from the treatment with sertraline sometimes counteracted these side effects, so that sexual desire and overall satisfaction with sex stayed the same as before the sertraline treatment. However, under the action of placebo the desire and satisfaction slightly improved.[72]

Some people experience persistent sexual side effects after they stop taking SSRIs.[73] This is known as Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction (PSSD). Common symptoms in these cases include genital anesthesia, erectile dysfunction, anhedonia, decreased libido, premature ejaculation, vaginal lubrication issues, and nipple insensitivity in women. Rates of PSSD are unknown, and there is no established treatment.[74]

Pregnancy

Antidepressant exposure (including sertraline) is associated with shorter average duration of pregnancy (by three days), increased risk of preterm delivery (by 55%), lower birth weight (by 75 g), and lower Apgar scores (by <0.4 points).[75][76] It is uncertain whether there is an increased rate of septal heart defects among children whose mothers were prescribed an SSRI in early pregnancy.[77][78]

Suicide

The FDA requires all antidepressants, including sertraline, to carry a boxed warning stating that antidepressants may increase the risk of suicide in persons younger than 25 years. This warning is based on statistical analyses conducted by two independent groups of FDA experts that found a 100% increase of suicidal ideation and behavior in children and adolescents, and a 50% increase of suicidal behavior in the 18–24 age group.[79][80][81]

Suicidal ideation and behavior in clinical trials are rare. For the above analysis, the FDA combined the results of 295 trials of 11 antidepressants for psychiatric indications in order to obtain statistically significant results. Considered separately, sertraline use in adults decreased the odds of suicidal behavior with a marginal statistical significance by 37%[81] or 50%[80] depending on the statistical technique used. The authors of the FDA analysis note that "given the large number of comparisons made in this review, chance is a very plausible explanation for this difference".[80] The more complete data submitted later by the sertraline manufacturer Pfizer indicated increased suicidal behavior.[82] Similarly, the analysis conducted by the UK MHRA found a 50% increase of odds of suicide-related events, not reaching statistical significance, in the patients on sertraline as compared to the ones on placebo.[83][84]

Concerns have been raised that suicidal acts among participants in multiple studies were not reported in published articles reporting the studies.[85]

Discontinuation syndrome

Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome is a condition that can occur following the interruption, dose reduction, or discontinuation of antidepressant drugs, including sertraline. The symptoms can include flu-like symptoms, "brain zaps," and disturbances in sleep, senses, movement, mood, and thinking. In most cases symptoms are mild, short-lived, and resolve without treatment. More severe cases are often successfully treated by temporary reintroduction of the drug with a slower tapering off rate.[86]

Overdose

Acute overdosage is often manifested by emesis, lethargy, ataxia, tachycardia and seizures. Plasma, serum or blood concentrations of sertraline and norsertraline, its major active metabolite, may be measured to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to aid in the medicolegal investigation of fatalities.[87] As with most other SSRIs its toxicity in overdose is considered relatively low.[58][88]

Interactions

Sertraline is a moderate inhibitor of CYP2D6 and CYP2B6 in vitro.[9] In clinical trials, however, its inhibition of CYP2D6 is weak.[89] Accordingly, in human trials it caused increased blood levels of CYP2D6 substrates such as metoprolol, dextromethorphan, desipramine, imipramine and nortriptyline, as well as the CYP3A4/CYP2D6 substrate haloperidol.[90][91][92] This effect is dose-dependent.[10][93] In a placebo-controlled study, the concomitant administration of sertraline and methadone caused a 40% increase in blood levels of the latter, which is primarily metabolized by CYP2B6.[94] Sertraline is often used in combination with stimulant medication for the treatment of co-morbid depression and/or anxiety in ADHD.[95] Amphetamine metabolism inhibits enzyme CYP2D6, but has not been known to interfere with sertraline metabolism.[96]

Sertraline had a slight inhibitory effect on the metabolism of diazepam, tolbutamide and warfarin, which are CYP2C9 or CYP2C19 substrates; this effect was not considered to be clinically relevant.[10] As expected from in vitro data, sertraline did not alter the human metabolism of the CYP3A4 substrates erythromycin, alprazolam, carbamazepine, clonazepam, and terfenadine; neither did it affect metabolism of the CYP1A2 substrate clozapine.

Sertraline had no effect on the actions of digoxin and atenolol, which are not metabolized in the liver.[7] Case reports suggest that taking sertraline with phenytoin or zolpidem may induce sertraline metabolism and decrease its efficacy,[97][98] and that taking sertraline with lamotrigine may increase the blood level of lamotrigine, possibly by inhibition of glucuronidation.[99]

Clinical reports indicate that interaction between sertraline and the MAOIs isocarboxazid and tranylcypromine may cause serotonin syndrome. In a placebo-controlled study in which sertraline was co-administered with lithium, 35% of the subjects experienced tremors, while none of those taking placebo did.[10]

According to the label, sertraline is contraindicated in individuals taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors or the antipsychotic pimozide (Orap). Sertraline concentrate contains alcohol, and is therefore contraindicated with disulfiram (Antabuse).[100] The prescribing information recommends that treatment of the elderly and patients with liver impairment "must be approached with caution." Due to the slower elimination of sertraline in these groups, their exposure to sertraline may be as high as three times the average exposure for the same dose.[7]

Pharmacology

Sertraline is a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor.[101] It targets the sodium dependent serotonin transporter to inhibit the re-uptake of serotonin by neurons. This increases the concentration of serotonin in the synaptic cleft, meaning more is available to act on the post synaptic neurons resulting in antidepressant effects.[101][102] Sertraline does not inhibit noradrenalin re-uptake, has little anticholinergic activity and has less sedative and cardiovascular effects than tricyclic antidepressant drugs.[102][103]

Mechanism of action

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 0.4 2.8 (IC50) |

Human | [105][106][107] | |

| NET | 420–817 925 (IC50) |

Human | [105][106][107] | |

| DAT | 22–25 315 (IC50) |

Human | [105][106][107] | |

| 5-HT1A | >35,000 | Human | [108] | |

| 5-HT2A | 2,207 | Rat | [107] | |

| 5-HT2C | 2,298 | Pig | [107] | |

| α1 | 36–480 | Human | [106][107][108] | |

| α2 | 477–4,100 | Human | [106][108] | |

| D2 | 10,700 | Human | [108] | |

| H1 | 24,000 | Human | [108] | |

| mACh | 427–2,100 | Human | [107][108][109] | |

| σ1 | 32–57 | Rat | [110][111] | |

| σ2 | 5,297 | Rat | [111] | |

| Values are Ki (nM), unless otherwise noted. The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to or inhibits the site. | ||||

Sertraline acts as a potent serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI),[112] with an affinity (Ki) for the serotonin transporter (SERT) of 0.4 nM and an IC50 value of 2.8 nM, according to a couple of studies.[105][107] It is highly selective in its inhibition of serotonin reuptake.[113] By inhibiting the reuptake of serotonin, sertraline increases extracellular levels of serotonin and thereby increases serotonergic neurotransmission in the brain. It is this action that is thought to be responsible for the antidepressant, anxiolytic, and antiobsessional effects of sertraline.

Sertraline does not have significant affinity for the norepinephrine transporter (NET) or the serotonin, dopamine, adrenergic, histamine, or acetylcholine receptors.[114][104] On the other hand, it does show high affinity for the dopamine transporter (DAT) and the sigma σ1 receptor (but not the σ2 receptor).[105][115] However, its affinity for SERT is greater by around 100-fold or more in comparison to its affinity for these other sites.[104][105][111]

Dopamine reuptake inhibition

Sertraline is an SSRI, but, uniquely among most antidepressants, it shows relatively high (nanomolar) affinity for the DAT in addition to the SERT.[105][116][117] As such, it has been suggested that clinically it may weakly inhibit the reuptake of dopamine,[118] particularly at high dosages.[119] For this reason, sertraline has sometimes been described as a serotonin–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SDRI).[120] This is relevant as dopamine is thought to be involved in the pathophysiology of depression, and increased dopaminergic neurotransmission by sertraline in addition to serotonin may have additional benefits against depression.[119]

Tatsumi et al. (1997) found Ki values of sertraline at the human SERT, DAT, and NET of 0.29, 25, and 420 nM, respectively.[105] The selectivity of sertraline for the SERT over the DAT was 86-fold.[105] In any case, of the wide assortment of antidepressants assessed in the study, sertraline showed the highest affinity of them all for the DAT, even higher than the norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs) nomifensine (Ki = 56 nM) and bupropion (Ki = 520 nM).[105][116] Sertraline also has similar affinity for the DAT as the NDRI methylphenidate (Ki = 24 nM).[105][116] Tametraline (CP-24,441), a very close analogue of sertraline and the compound from which sertraline was originally derived, is an NDRI that was never marketed.[121]

Single doses of 50 to 200 mg sertraline have been found to result in peak plasma concentrations of 20 to 55 ng/mL (65–180 nM),[114] while chronic treatment with 200 mg/day sertraline, the maximum recommended dosage, has been found to result in maximal plasma levels of 118 to 166 ng/mL (385–542 nM).[10] However, sertraline is highly protein-bound in plasma, with a bound fraction of 98.5%.[10] Hence, only 1.5% is free and theoretically bioactive.[10] Based on this percentage, free concentrations of sertraline would be 2.49 ng/mL (8.13 nM) at the very most, which is only about one-third of the Ki value that Tatsumi et al. found with sertraline at the DAT.[105] A very high dosage of sertraline of 400 mg/day has been found to produce peak plasma concentrations of about 250 ng/mL (816 nM).[10] This can be estimated to result in a free concentration of 3.75 ng/mL (12.2 nM), which is still only about half of the Ki of sertraline for the DAT.[105]

As such, it seems unlikely that sertraline would produce much inhibition of dopamine reuptake even at clinically used dosages well in excess of the recommended maximum clinical dosage.[118] This is in accordance with its 86-fold selectivity for the SERT over the DAT according to Tatsumi et al. and hence the fact that nearly 100-fold higher levels of sertraline would be necessary to also inhibit dopamine reuptake.[118] In accordance, while sertraline has very low abuse potential and may even be aversive at clinical dosages,[122] a case report of sertraline abuse described dopaminergic-like effects such as euphoria, mental overactivity, and hallucinations only at a dosage 56 times the normal maximum and 224 times the normal minimum.[123] For these reasons, significant inhibition of dopamine reuptake by sertraline at clinical dosages is controversial, and occupation by sertraline of the DAT is thought by many experts to not be clinically relevant.[124]

Sigma receptor antagonism

Sertraline has relatively high (nanomolar) affinity for the sigma σ1 receptor.[110][111] Conversely, it has low (micromolar) and insignificant affinity for the σ2 receptor.[110][111] It acts as an antagonist of the σ1 receptor, and is able to reverse σ1 receptor-dependent actions of fluvoxamine, a potent agonist of the receptor, in vitro.[111] However, the affinity of sertraline for the σ1 receptor is more than 100-fold lower than for the SERT.[110][111] Although there could be a role for the σ1 receptor in the pharmacology of sertraline, the significance of this receptor in its actions is unclear and perhaps questionable.[114]

Sertraline is associated with a significantly higher incidence of diarrhea than other SSRIs, especially at higher doses.[21] Agonists of the σ1 receptor such as igmesine have been found to inhibit intestinal secretion and bacteria-induced secretory diarrhea in animal studies,[125] and igmesine showed preliminary evidence of efficacy for the treatment of diarrhea in a small clinical trial.[126][127] Sertraline is the only SSRI that acts as an antagonist of the σ1 receptor,[111][110] so this action could in theory be responsible for its higher relative incidence of diarrhea.

Neurosteroidogenesis enhancement

Sertraline has been found to directly act on the enzyme 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) and modulate its activity, thereby enhancing the conversion of 5α-dihydroprogesterone into the neurosteroid allopregnanolone and thus increasing the production of allopregnanolone in the brain.[128][129] The same is true for certain other SSRIs including fluoxetine and paroxetine.[128][129] However, a subsequent study failed to reproduce these findings, and a direct interaction of SSRIs with 3α-HSD is controversial.[130][129][131] In any case, another study found that, at least in the case of fluoxetine and its active metabolite norfluoxetine, these drugs normalized low allopregnanolone levels in socially isolated mice and at low doses that were inactive on serotonin reuptake (10- to 50-fold lower, specifically).[132][131] On the basis of these results, SSRIs like fluoxetine and norfluoxetine were described as selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs).[132]

Pharmacokinetics

Sertraline is absorbed slowly when taken orally, achieving its maximal concentration in the plasma 4 to 6 hours after ingestion. In the blood, it is 98.5% bound to plasma proteins and a half life of 25 to 26 hours.[102] Sertraline is metabolised in the liver by demethylation to an inactive metabolite.[133] According to in vitro studies, sertraline is metabolized by multiple cytochrome 450 isoforms: CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP2B6, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4. It appeared unlikely that inhibition of any single isoform could cause clinically significant changes in sertraline pharmacokinetics.[6][134] No differences in sertraline pharmacokinetics were observed between people with high and low activity of CYP2D6;[135] however, poor CYP2C19 metabolizers had a 1.5-times-higher level of sertraline than normal metabolizers.[136] In vitro data also indicate that the inhibition of CYP2B6 should have even greater effect than the inhibition of CYP2C19, while the contribution of CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 to the metabolism of sertraline would be minor. These conclusions have not been verified in human studies.[6] Sertraline can be deaminated in vitro by monoamine oxidases; however, this metabolic pathway has never been studied in vivo.[6] The major metabolite of sertraline, desmethylsertraline, is about 50 times weaker as a serotonin transporter inhibitor than sertraline and its clinical effect is negligible.[106]

Non-amine metabolites may also contribute to the antidepressant effects of this medication. Sertraline deaminated is O-2098, a compound that has been found to inhibit the dopamine reuptake transporter proteins in spite of its lack of a nitrogen atom.[137]

Its chief active metabolite is norsertraline (N-desmethylsertraline) which is significantly less biologically active than its parent compound.[138]

History

The history of sertraline dates back to the early 1970s, when Pfizer chemist Reinhard Sarges invented a novel series of psychoactive compounds based on the structure of the neuroleptic chlorprothixene.[139][140] Further work on these compounds led to lometraline and then to tametraline, a norepinephrine and weaker dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Development of tametraline was soon stopped because of undesired stimulant effects observed in animals. A few years later, in 1977, pharmacologist Kenneth Koe, after comparing the structural features of a variety of reuptake inhibitors, became interested in the tametraline series. He asked another Pfizer chemist, Willard Welch, to synthesize some previously unexplored tametraline derivatives. Welch generated a number of potent norepinephrine and triple reuptake inhibitors, but to the surprise of the scientists, one representative of the generally inactive cis-analogs was a serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Welch then prepared stereoisomers of this compound, which were tested in vivo by animal behavioral scientist Albert Weissman. The most potent and selective (+)-isomer was taken into further development and eventually named sertraline. Weissman and Koe recalled that the group did not set up to produce an antidepressant of the SSRI type—in that sense their inquiry was not "very goal driven", and the discovery of the sertraline molecule was serendipitous. According to Welch, they worked outside the mainstream at Pfizer, and even "did not have a formal project team". The group had to overcome initial bureaucratic reluctance to pursue sertraline development, as Pfizer was considering licensing an antidepressant candidate from another company.[139][141][142]

Sertraline was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1991 based on the recommendation of the Psychopharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee; it had already become available in the United Kingdom the previous year.[143] The FDA committee achieved a consensus that sertraline was safe and effective for the treatment of MDD.

Sertraline entered the Australian market in 1994 and became the most often prescribed antidepressant in 1996 (2004 data).[144] It was measured as among the top ten drugs ranked by cost to the Australian government in 1998 and 2000–01, having cost $45 million and $87 million in subsidies respectively.[145][146] Sertraline is less popular in the UK (2003 data) and Canada (2006 data)—in both countries it was fifth (among drugs marketed for the treatment of MDD, or antidepressants), based on the number of prescriptions.[147][148]

Until 2002, sertraline was only approved for use in adults ages 18 and over; that year, it was approved by the FDA for use in treating children aged 6 or older with severe OCD. In 2003, the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency issued a guidance that, apart from fluoxetine (Prozac), SSRIs are not suitable for the treatment of depression in patients under 18.[149][150] However, sertraline can still be used in the UK for the treatment of OCD in children and adolescents.[151] In 2005, the FDA added a boxed warning concerning pediatric suicidal behavior to all antidepressants, including sertraline. In 2007, labeling was again changed to add a warning regarding suicidal behavior in young adults ages 18 to 24.[152]

Society and culture

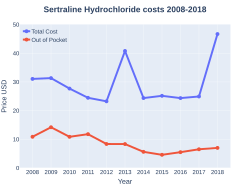

Cost

In the United States, the wholesale cost is about US$1.50 per month as of 2018.[15] In 2017, it was the 14th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States with over 38 million prescriptions.[18][17]

-

Sertraline costs (US)

-

Sertraline prescriptions (US)

Generic availability

The U.S. patent for Zoloft expired in 2006,[153] and sertraline is now available in generic form and is marketed under many brand names worldwide.[1]

In May 2020, the FDA placed sertraline on the list of drugs currently facing a shortage.[154]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Sertraline". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "SERTRALINE oral - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Sertraline (Zoloft) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 4 May 2020. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ Hubbard, John R.; Martin, Peter R. (2001). Substance Abuse in the Mentally and Physically Disabled. CRC Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780824744977. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Obach RS, Cox LM, Tremaine LM (February 2005). "Sertraline is metabolized by multiple cytochrome P450 enzymes, monoamine oxidases, and glucuronyl transferases in human: an in vitro study". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 33 (2): 262–70. doi:10.1124/dmd.104.002428. PMID 15547048. S2CID 7254643.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Sertraline FDA Label Wayback Machine at the Wayback Machine (archived 30 October 2020) Last updated May 2014

- ↑ Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B. (2010) Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, Twelfth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 9780071769396

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Obach RS, Walsky RL, Venkatakrishnan K, Gaman EA, Houston JB, Tremaine LM (January 2006). "The utility of in vitro cytochrome P450 inhibition data in the prediction of drug-drug interactions". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 316 (1): 336–48. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.093229. PMID 16192315. S2CID 12975686.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 DeVane CL, Liston HL, Markowitz JS (2002). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of sertraline". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 41 (15): 1247–66. doi:10.2165/00003088-200241150-00002. PMID 12452737. S2CID 28720641.

- ↑ DeVane CL, Donovan JL, Liston HL, Markowitz JS, Cheng KT, Risch SC, Willard L (February 2004). "Comparative CYP3A4 inhibitory effects of venlafaxine, fluoxetine, sertraline, and nefazodone in healthy volunteers". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 24 (1): 4–10. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000104908.75206.26. PMID 14709940. S2CID 25826168.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 "Sertraline Hydrochloride". Drugs.com. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ↑ "Sertraline (Zoloft) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 20 June 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "NADAC as of 2018-01-03". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ↑ Grohol, John M. (12 October 2017). "Top 25 Psychiatric Medications for 2016". Psych Central. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Sertraline Hydrochloride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. 23 December 2019. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ "Zoloft Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 17 September 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ↑ "Sertraline Sandoz Tablet". NPS MedicineWise. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Sanchez C, Reines EH, Montgomery SA (July 2014). "A comparative review of escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline: Are they all alike?". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 29 (4): 185–96. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000023. PMC 4047306. PMID 24424469.

- ↑ Cohen D (2007). "Should the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in child and adolescent depression be banned?". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 76 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1159/000096360. PMID 17170559. S2CID 1112192.

- ↑ Banerjee S, Hellier J, Romeo R, Dewey M, Knapp M, Ballard C, Baldwin R, Bentham P, Fox C, Holmes C, Katona C, Lawton C, Lindesay J, Livingston G, McCrae N, Moniz-Cook E, Murray J, Nurock S, Orrell M, O'Brien J, Poppe M, Thomas A, Walwyn R, Wilson K, Burns A (February 2013). "Study of the use of antidepressants for depression in dementia: the HTA-SADD trial--a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of sertraline and mirtazapine". Health Technology Assessment. 17 (7): 1–166. doi:10.3310/hta17070. PMC 4782811. PMID 23438937.

- ↑ Parker G, Roy K, Wilhelm K, Mitchell P (February 2001). "Assessing the comparative effectiveness of antidepressant therapies: a prospective clinical practice study". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62 (2): 117–25. doi:10.4088/JCP.v62n0209. PMID 11247097.

- ↑ Anderson IM (1998). "SSRIS versus tricyclic antidepressants in depressed inpatients: a meta-analysis of efficacy and tolerability". Depression and Anxiety. 7 Suppl 1 (S1): 11–7. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1998)7:1+<11::AID-DA4>3.0.CO;2-I. PMID 9597346.

- ↑ Hirschfeld RM (May 1999). "Efficacy of SSRIs and newer antidepressants in severe depression: comparison with TCAs". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 60 (5): 326–35. doi:10.4088/JCP.v60n0511. PMID 10362442.

- ↑ Lépine JP, Goger J, Blashko C, Probst C, Moles MF, Kosolowski J, Scharfetter B, Lane RM (September 2000). "A double-blind study of the efficacy and safety of sertraline and clomipramine in outpatients with severe major depression". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 15 (5): 263–71. doi:10.1097/00004850-200015050-00003. PMID 10993128.

- ↑ Amsterdam JD (1998). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor efficacy in severe and melancholic depression". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 12 (3 Suppl B): S99–111. doi:10.1177/0269881198012003061. PMID 9808081. S2CID 12824395.

- ↑ Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Geddes JR, Higgins JP, Churchill R, Watanabe N, Nakagawa A, Omori IM, McGuire H, Tansella M, Barbui C (February 2009). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 373 (9665): 746–58. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. PMID 19185342. S2CID 35858125.

- Lay summary in: "Zoloft, Lexapro the Best of Newer Antidepressants". The Washington Post. 29 January 2009.

- ↑ Papakostas GI, Fava M (October 2006). "A metaanalysis of clinical trials comparing moclobemide with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of major depressive disorder". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 51 (12): 783–90. doi:10.1177/070674370605101208. PMID 17168253.

- ↑ Feiger A, Kiev A, Shrivastava RK, Wisselink PG, Wilcox CS (1996). "Nefazodone versus sertraline in outpatients with major depression: focus on efficacy, tolerability, and effects on sexual function and satisfaction". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 57. 57 Suppl 2: 53–62. PMID 8626364.

- ↑ Kavoussi RJ, Segraves RT, Hughes AR, Ascher JA, Johnston JA (December 1997). "Double-blind comparison of bupropion sustained release and sertraline in depressed outpatients". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 (12): 532–7. doi:10.4088/JCP.v58n1204. PMID 9448656.

- ↑ For the review, see:Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Lohr KN, Gaynes BN, Carey TS (September 2005). "Efficacy and safety of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of major depressive disorder". Annals of Internal Medicine. 143 (6): 415–26. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00006. PMID 16172440. S2CID 10321621.

- ↑ Cipriani A, La Ferla T, Furukawa TA, Signoretti A, Nakagawa A, Churchill R, McGuire H, Barbui C (April 2010). "Sertraline versus other antidepressive agents for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006117. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006117.pub4. PMC 4163971. PMID 20393946.

- ↑ Muijsers RB, Plosker GL, Noble S (2002). "Sertraline: a review of its use in the management of major depressive disorder in elderly patients". Drugs & Aging. 19 (5): 377–92. doi:10.2165/00002512-200219050-00006. PMID 12093324.

- ↑ Schneider LS, Nelson JC, Clary CM, Newhouse P, Krishnan KR, Shiovitz T, Weihs K, et al. (Sertraline Elderly Depression Study Group) (July 2003). "An 8-week multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in elderly outpatients with major depression". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (7): 1277–85. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1277. PMID 12832242.

- ↑ Thorlund K, Druyts E, Wu P, Balijepalli C, Keohane D, Mills E (2015). "Comparative efficacy and safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors in older adults: a network meta-analysis". J Am Geriatr Soc. 19 (63): 1002–1009. doi:10.1111/jgs.13395. PMID 25945410.

- ↑ Geller DA, Biederman J, Stewart SE, Mullin B, Martin A, Spencer T, Faraone SV (November 2003). "Which SSRI? A meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy trials in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (11): 1919–28. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1919. PMID 14594734.

- ↑ Flament MF, Bisserbe JC (1997). "Pharmacologic treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: comparative studies". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58. 58 Suppl 12: 18–22. PMID 9393392.

- ↑ Math SB, Janardhan Reddy YC (19 July 2007). "Issues In The Pharmacological Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: First-Line Treatment Options for OCD". medscape.com. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ↑ Blier P, Habib R, Flament MF (June 2006). "Pharmacotherapies in the management of obsessive-compulsive disorder" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 51 (7): 417–30. doi:10.1177/070674370605100703. PMID 16838823. S2CID 17133521. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 February 2010.

- ↑ Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team (October 2004). "Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 292 (16): 1969–76. doi:10.1001/jama.292.16.1969. PMID 15507582.

- ↑ Sousa MB, Isolan LR, Oliveira RR, Manfro GG, Cordioli AV (July 2006). "A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral group therapy and sertraline in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 (7): 1133–9. doi:10.4088/JCP.v67n0717. PMID 16889458. S2CID 25130472.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Hirschfeld RM (2000). "Sertraline in the treatment of anxiety disorders". Depression and Anxiety. 11 (4): 139–57. doi:10.1002/1520-6394(2000)11:4<139::AID-DA1>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 10945134.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Clayton AH, Stewart RS, Fayyad R, Clary CM (May 2006). "Sex differences in clinical presentation and response in panic disorder: pooled data from sertraline treatment studies". Archives of Women's Mental Health. 9 (3): 151–7. doi:10.1007/s00737-005-0111-y. PMID 16292466. S2CID 20606054.

- ↑ Hansen RA, Gaynes BN, Gartlehner G, Moore CG, Tiwari R, Lohr KN (May 2008). "Efficacy and tolerability of second-generation antidepressants in social anxiety disorder". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 23 (3): 170–9. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f4224a. PMC 2657552. PMID 18408531.

- ↑ Davidson JR (2006). "Pharmacotherapy of social anxiety disorder: what does the evidence tell us?". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 67 Suppl 12: 20–6. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.002. PMID 17092192.

- ↑ Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, Ginsburg GS, Rynn MA, McCracken J, Waslick B, Iyengar S, March JS, Kendall PC (December 2008). "Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety". The New England Journal of Medicine. 359 (26): 2753–66. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0804633. PMC 2702984. PMID 18974308.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Gale CK, Millichamp J (October 2011). "Generalised anxiety disorder". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2011. PMC 3275153. PMID 22030083.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Marjoribanks J, Brown J, O'Brien PM, Wyatt K (June 2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD001396. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd001396.pub3. PMC 7073417. PMID 23744611. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ Pearlstein T (2002). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual dysphoric disorder: the emerging gold standard?". Drugs. 62 (13): 1869–85. doi:10.2165/00003495-200262130-00004. PMID 12215058. S2CID 46974228.

- ↑ Ackermann RT, Williams JW (April 2002). "Rational treatment choices for non-major depressions in primary care: an evidence-based review". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 17 (4): 293–301. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10350.x. PMC 1495030. PMID 11972726.

- ↑ Abdel-Hamid IA (September 2006). "Pharmacologic treatment of rapid ejaculation: levels of evidence-based review". Current Clinical Pharmacology. 1 (3): 243–54. doi:10.2174/157488406778249352. PMID 18666749.

- ↑ Waldinger MD (November 2007). "Premature ejaculation: state of the art". The Urologic Clinics of North America. 34 (4): 591–9, vii–viii. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2007.08.011. PMID 17983899.

- ↑ McMahon CG, Porst H (October 2011). "Oral agents for the treatment of premature ejaculation: review of efficacy and safety in the context of the recent International Society for Sexual Medicine criteria for lifelong premature ejaculation". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (10): 2707–25. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02386.x. PMID 21771283.

- ↑ Pratchett LC, Daly K, Bierer LM, Yehuda R (October 2011). "New approaches to combining pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 12 (15): 2339–54. doi:10.1517/14656566.2011.604030. PMID 21819273. S2CID 5949488.

- ↑ Davis LL, Frazier EC, Williford RB, Newell JM (2006). "Long-term pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder". CNS Drugs. 20 (6): 465–76. doi:10.2165/00023210-200620060-00003. PMID 16734498. S2CID 35429551.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Taylor D, Paton C, Shitij K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ↑ Brayfield, A, ed. (13 August 2013). Fluoxetine Hydrochloride. Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ "Side effects of antidepressant medications". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer Health. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ Fava M, Judge R, Hoog SL, Nilsson ME, Koke SC (November 2000). "Fluoxetine versus sertraline and paroxetine in major depressive disorder: changes in weight with long-term treatment". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 61 (11): 863–7. doi:10.4088/JCP.v61n1109. PMID 11105740.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Maina G, Albert U, Salvi V, Bogetto F (October 2004). "Weight gain during long-term treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a prospective comparison between serotonin reuptake inhibitors". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 65 (10): 1365–71. doi:10.4088/JCP.v65n1011. PMID 15491240.

- ↑ Schmitt JA, Kruizinga MJ, Riedel WJ (September 2001). "Non-serotonergic pharmacological profiles and associated cognitive effects of serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 15 (3): 173–9. doi:10.1177/026988110101500304. PMID 11565624. S2CID 26017110.

- ↑ Siepmann M, Grossmann J, Mück-Weymann M, Kirch W (July 2003). "Effects of sertraline on autonomic and cognitive functions in healthy volunteers". Psychopharmacology. 168 (3): 293–8. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1448-4. PMID 12692706. S2CID 19178740.

- ↑ Gorenstein C, de Carvalho SC, Artes R, Moreno RA, Marcourakis T (March 2006). "Cognitive performance in depressed patients after chronic use of antidepressants". Psychopharmacology. 185 (1): 84–92. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-0274-2. PMID 16485140. S2CID 594353.

- ↑ Günther T, Holtkamp K, Jolles J, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Konrad K (August 2005). "The influence of sertraline on attention and verbal memory in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders". Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 15 (4): 608–18. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.536.6334. doi:10.1089/cap.2005.15.608. PMID 16190792.

- ↑ Borkowska A, Pilaczyńska E, Araszkiewicz A, Rybakowski J (2002). "[The effect of sertraline on cognitive functions in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder]". Psychiatria Polska. 36 (6 Suppl): 289–95. PMID 12647451.

- ↑ Schmitt JA, Ramaekers JG, Kruizinga MJ, van Boxtel MP, Vuurman EF, Riedel WJ (September 2002). "Additional dopamine reuptake inhibition attenuates vigilance impairment induced by serotonin reuptake inhibition in man". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 16 (3): 207–14. doi:10.1177/026988110201600303. PMID 12236626. S2CID 25351919.

- ↑ Garrett AR, Hawley JS (April 2018). "SSRI-associated bruxism: A systematic review of published case reports". Neurology. Clinical Practice. 8 (2): 135–141. doi:10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000433. PMC 5914744. PMID 29708207.

- ↑ Fitzgerald K, Healy D (1995). "Dystonias and dyskinesias of the jaw associated with the use of SSRIs". Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 10 (3): 215–219. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.662.9222. doi:10.1002/hup.470100308.

- ↑ Ferguson JM (2001). "The effects of antidepressants on sexual functioning in depressed patients: a review". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62. 62 Suppl 3: 22–34. PMID 11229450.

- ↑ Croft H, Settle E, Houser T, Batey SR, Donahue RM, Ascher JA (April 1999). "A placebo-controlled comparison of the antidepressant efficacy and effects on sexual functioning of sustained-release bupropion and sertraline". Clinical Therapeutics. 21 (4): 643–58. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88317-4. PMID 10363731.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 449. ISBN 9780890425558.

- ↑ Bala A, Nguyen HM, Hellstrom WJ (January 2018). "Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction: A Literature Review". Sexual Medicine Reviews. 6 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.07.002. PMID 28778697.

- ↑ Ross LE, Grigoriadis S, Mamisashvili L, Vonderporten EH, Roerecke M, Rehm J, Dennis CL, Koren G, Steiner M, Mousmanis P, Cheung A (April 2013). "Selected pregnancy and delivery outcomes after exposure to antidepressant medication: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (4): 436–43. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.684. PMID 23446732.

- ↑ Lattimore, Keri A.; Donn, Steven M.; Kaciroti, Niko; Kemper, Alex R.; Neal, Charles R.; Vazquez, Delia M. (2005). "Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Use during Pregnancy and Effects on the Fetus and Newborn: A Meta-Analysis". Journal of Perinatology. 25 (9): 595–604. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211352. PMID 16015372.

- ↑ Pedersen LH, Henriksen TB, Vestergaard M, Olsen J, Bech BH (September 2009). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and congenital malformations: population based cohort study". BMJ. 339 (sep23 1): b3569. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3569. PMC 2749925. PMID 19776103.

- ↑ Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, Cohen LS, Holmes LB, Franklin JM, Mogun H, Levin R, Kowal M, Setoguchi S, Hernández-Díaz S (June 2014). "Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects". The New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (25): 2397–407. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1312828. PMC 4062924. PMID 24941178.

- ↑ Levenson M, Holland C. "Antidepressants and Suicidality in Adults: Statistical Evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 Stone MB, Jones ML (17 November 2006). "Clinical review: relationship between antidepressant drugs and suicidality in adults" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 11–74. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Levenson M, Holland C (17 November 2006). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 75–140. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ↑ Pfizer Inc. (30 November 2006). "Memorandum from Pfizer Global Pharmaceuticals Re: DOCKET: 2006N-0414 –"Suicidality data from adult antidepressant trials" Background package for December 13 Advisory Committee" (PDF). FDA DOCKET 2006N-0414. FDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ↑ "Report of the CSM expert working group on the safety of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants" (PDF). MHRA. December 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ↑ Gunnell D, Saperia J, Ashby D (February 2005). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and suicide in adults: meta-analysis of drug company data from placebo controlled, randomised controlled trials submitted to the MHRA's safety review". BMJ. 330 (7488): 385. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7488.385. PMC 549105. PMID 15718537.

- ↑ Healy D, Cattell D (July 2003). "Interface between authorship, industry and science in the domain of therapeutics". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 183: 22–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.183.1.22. PMID 12835239.

- ↑ Warner CH, Bobo W, Warner C, Reid S, Rachal J (August 2006). "Antidepressant discontinuation syndrome". American Family Physician. 74 (3): 449–56. PMID 16913164.

- ↑ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, California: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1399–1400.

- ↑ White N, Litovitz T, Clancy C (December 2008). "Suicidal antidepressant overdoses: a comparative analysis by antidepressant type". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 4 (4): 238–50. doi:10.1007/BF03161207. PMC 3550116. PMID 19031375.

- ↑ "Drug Development and Drug Interactions: Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers". Archived from the original on 4 November 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ Ozdemir V, Naranjo CA, Herrmann N, Shulman RW, Sellers EM, Reed K, Kalow W (February 1998). "The extent and determinants of changes in CYP2D6 and CYP1A2 activities with therapeutic doses of sertraline". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 18 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1097/00004714-199802000-00009. PMID 9472843.

- ↑ Alfaro CL, Lam YW, Simpson J, Ereshefsky L (April 1999). "CYP2D6 status of extensive metabolizers after multiple-dose fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, or sertraline". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 19 (2): 155–63. doi:10.1097/00004714-199904000-00011. PMID 10211917.

- ↑ Alfaro CL, Lam YW, Simpson J, Ereshefsky L (January 2000). "CYP2D6 inhibition by fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine in a crossover study: intraindividual variability and plasma concentration correlations". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 40 (1): 58–66. doi:10.1177/00912700022008702. PMID 10631623.

- ↑ Preskorn SH, Greenblatt DJ, Flockhart D, Luo Y, Perloff ES, Harmatz JS, Baker B, Klick-Davis A, Desta Z, Burt T (February 2007). "Comparison of duloxetine, escitalopram, and sertraline effects on cytochrome P450 2D6 function in healthy volunteers". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 27 (1): 28–34. doi:10.1097/00004714-200702000-00005. PMID 17224709. S2CID 28468404.

- ↑ Hamilton SP, Nunes EV, Janal M, Weber L (2000). "The effect of sertraline on methadone plasma levels in methadone-maintenance patients". The American Journal on Addictions. 9 (1): 63–9. doi:10.1080/10550490050172236. PMID 10914294.

- ↑ Brown, Thomas E.; Brown, Thomas E. (2009). ADHD comorbidities: handbook for ADHD complications in children and adults. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 978-1-58562-158-3. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). Medication Guide. United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ↑ Allard S, Sainati SM, Roth-Schechter BF (February 1999). "Coadministration of short-term zolpidem with sertraline in healthy women". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 39 (2): 184–91. doi:10.1177/00912709922007624. PMID 11563412.

- ↑ Haselberger MB, Freedman LS, Tolbert S (April 1997). "Elevated serum phenytoin concentrations associated with coadministration of sertraline". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 17 (2): 107–9. doi:10.1097/00004714-199704000-00008. PMID 10950473.

- ↑ Kaufman KR, Gerner R (April 1998). "Lamotrigine toxicity secondary to sertraline". Seizure. 7 (2): 163–5. doi:10.1016/S1059-1311(98)80074-5. PMID 9627209. S2CID 35861342.

- ↑ "Sertraline Oral Concentrate". drugs.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Hitchings, Andrew; Lonsdale, Dagan; Burrage, Daniel; Baker, Emma (2015). Top 100 drugs : clinical pharmacology and practical prescribing. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7020-5516-4.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 Murdoch, D; McTavish, D (October 1992). "Sertraline. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic potential in depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder". Drugs. 44 (4): 604–24. doi:10.2165/00003495-199244040-00007. PMID 1281075.

- ↑ "Sertraline". www.drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 Roth BL, Driscol J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ↑ 105.00 105.01 105.02 105.03 105.04 105.05 105.06 105.07 105.08 105.09 105.10 105.11 105.12 Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (December 1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". European Journal of Pharmacology. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 106.3 106.4 106.5 Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, Nemeroff CB (December 1997). "Neurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of antidepressants and their metabolites". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 283 (3): 1305–22. PMID 9400006.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 107.2 107.3 107.4 107.5 107.6 107.7 Owens MJ, Knight DL, Nemeroff CB (September 2001). "Second-generation SSRIs: human monoamine transporter binding profile of escitalopram and R-fluoxetine". Biological Psychiatry. 50 (5): 345–50. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01145-3. PMID 11543737.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 108.2 108.3 108.4 108.5 Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E (May 1994). "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology. 114 (4): 559–65. doi:10.1007/bf02244985. PMID 7855217.

- ↑ Stanton T, Bolden-Watson C, Cusack B, Richelson E (June 1993). "Antagonism of the five cloned human muscarinic cholinergic receptors expressed in CHO-K1 cells by antidepressants and antihistaminics". Biochemical Pharmacology. 45 (11): 2352–4. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90211-e. PMID 8100134.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 110.2 110.3 110.4 Albayrak Y, Hashimoto K (2017). Sigma-1 Receptor Agonists and Their Clinical Implications in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 964. pp. 153–161. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50174-1_11. ISBN 978-3-319-50172-7. PMID 28315270.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 111.3 111.4 111.5 111.6 111.7 Hindmarch I, Hashimoto K (April 2010). "Cognition and depression: the effects of fluvoxamine, a sigma-1 receptor agonist, reconsidered". Human Psychopharmacology. 25 (3): 193–200. doi:10.1002/hup.1106. PMID 20373470.

- ↑ Meyer JH, Wilson AA, Sagrati S, Hussey D, Carella A, Potter WZ, Ginovart N, Spencer EP, Cheok A, Houle S (May 2004). "Serotonin transporter occupancy of five selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors at different doses: an [11C]DASB positron emission tomography study". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (5): 826–35. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.5.826. PMID 15121647.

- ↑ Hilal-Dandan, Randa; Brunton, Laurence; Goodman, Louis Sanford (2013). Goodman and Gilman Manual of Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Second ed.). McGraw Hill Professional. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-07-176917-4. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 114.2 MacQueen G, Born L, Steiner M (2001). "The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline: its profile and use in psychiatric disorders". CNS Drug Reviews. 7 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00188.x. PMC 6741657. PMID 11420570.

- ↑ Hashimoto K (September 2009). "Sigma-1 receptors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: clinical implications of their relationship". Central Nervous System Agents in Medicinal Chemistry. 9 (3): 197–204. doi:10.2174/1871524910909030197. PMID 20021354.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 116.2 Richelson E (May 2001). "Pharmacology of antidepressants". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 76 (5): 511–27. doi:10.4065/76.5.511. PMID 11357798.

- ↑ Hemmings, Hugh C.; Egan, Talmage D. (2012). Pharmacology and Physiology for Anesthesia E-Book: Foundations and Clinical Application. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 183–. ISBN 978-1-4557-3793-2. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 118.2 Lemke, Thomas L.; Williams, David A. (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 569–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 Dunlop BW, Nemeroff CB (March 2007). "The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression". Archives of General Psychiatry. 64 (3): 327–37. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.327. PMID 17339521.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Roger N. (2003). The Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurologic and Psychiatric Disease. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 738–. ISBN 978-0-7506-7360-0. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ Lemke, Thomas L.; Williams, David A. (2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 600–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ Nutt DJ (December 2003). "Death and dependence: current controversies over the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 17 (4): 355–64. doi:10.1177/0269881103174019. PMID 14870946. S2CID 23689568.

- ↑ D'Urso, P. (1996). "Abuse of Sertraline". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 21 (5): 359–360. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.1996.tb00031.x. PMID 9119919.

- ↑ Stahl, Stephen M. (2013). Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: Neuroscientific Basis and Practical Applications. Cambridge University Press. pp. 530–. ISBN 978-1-139-83305-9. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ Sorbera, L.A.; Silvestre, J.; Castañer, J. (1999). "Igmesine Hydrochloride". Drugs of the Future. 24 (2): 133. doi:10.1358/dof.1999.024.02.474038.

- ↑ Volz HP, Stoll KD (November 2004). "Clinical trials with sigma ligands". Pharmacopsychiatry. 37 Suppl 3: S214–20. doi:10.1055/s-2004-832680. PMID 15547788.

- ↑ Kent AJ, Banks MR (September 2010). "Pharmacological management of diarrhea". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 39 (3): 495–507. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2010.08.003. PMID 20951914.

- ↑ 128.0 128.1 Griffin LD, Mellon SH (November 1999). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors directly alter activity of neurosteroidogenic enzymes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (23): 13512–7. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9613512G. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.23.13512. PMC 23979. PMID 10557352.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 129.2 Uzunova V, Sampson L, Uzunov DP (June 2006). "Relevance of endogenous 3α-reduced neurosteroids to depression and antidepressant action". Psychopharmacology. 186 (3): 351–61. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-0201-6. PMID 16249906. S2CID 11184413.

- ↑ Trauger JW, Jiang A, Stearns BA, LoGrasso PV (November 2002). "Kinetics of allopregnanolone formation catalyzed by human 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type III (AKR1C2)". Biochemistry. 41 (45): 13451–9. doi:10.1021/bi026109w. PMID 12416991.

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 Gunn BG, Brown AR, Lambert JJ, Belelli D (2011). "Neurosteroids and GABA(A) Receptor Interactions: A Focus on Stress". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 5: 131. doi:10.3389/fnins.2011.00131. PMC 3230140. PMID 22164129.

- ↑ 132.0 132.1 Pinna G, Costa E, Guidotti A (February 2009). "SSRIs act as selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs) at low doses that are inactive on 5-HT reuptake". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 9 (1): 24–30. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2008.12.006. PMC 2670606. PMID 19157982.

- ↑ Warrington, SJ (December 1991). "Clinical implications of the pharmacology of sertraline". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 6 Suppl 2: 11–21. doi:10.1097/00004850-199112002-00004. PMID 1806626.

- ↑ Kobayashi K, Ishizuka T, Shimada N, Yoshimura Y, Kamijima K, Chiba K (July 1999). "Sertraline N-demethylation is catalyzed by multiple isoforms of human cytochrome P-450 in vitro". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 27 (7): 763–6. PMID 10383917.

- ↑ Hamelin BA, Turgeon J, Vallée F, Bélanger PM, Paquet F, LeBel M (November 1996). "The disposition of fluoxetine but not sertraline is altered in poor metabolizers of debrisoquin". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 60 (5): 512–21. doi:10.1016/S0009-9236(96)90147-2. PMID 8941024.

- ↑ Wang JH, Liu ZQ, Wang W, Chen XP, Shu Y, He N, Zhou HH (July 2001). "Pharmacokinetics of sertraline in relation to genetic polymorphism of CYP2C19". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 70 (1): 42–7. doi:10.1067/mcp.2001.116513. PMID 11452243.

- ↑ Madras BK, Fahey MA, Miller GM, De La Garza R, Goulet M, Spealman RD, Meltzer PC, George SR, O'Dowd BF, Bonab AA, Livni E, Fischman AJ (October 2003). "Non-amine-based dopamine transporter (reuptake) inhibitors retain properties of amine-based progenitors". European Journal of Pharmacology. 479 (1–3): 41–51. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.055. PMID 14612136.

- ↑ Ciraulo, DA; Shader, RI, eds. (2011). Pharmacotherapy of Depression. SpringerLink (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Humana Press. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-435-7. ISBN 978-1-60327-434-0.

- ↑ 139.0 139.1 The most complete account of sertraline discovery, targeted at chemists, see: Welch WM (1995). Discovery and Development of Sertraline. Advances in Medicinal Chemistry. Vol. 3. pp. 113–148. doi:10.1016/S1067-5698(06)80005-2. ISBN 978-1-55938-798-9.

- ↑ Sarges R, Tretter JR, Tenen SS, Weissman A (September 1973). "5,8-Disubstituted 1-aminotetralins. A class of compounds with a novel profile of central nervous system activity". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 16 (9): 1003–11. doi:10.1021/jm00267a010. PMID 4795663.

- ↑ See also: Mullin R (2006). "ACS Award for Team Innovation". Chemical & Engineering News. 84 (5): 45–52. doi:10.1021/cen-v084n010.p045.

- ↑ A short blurb on the history of sertraline, see: Couzin J (July 2005). "The brains behind blockbusters". Science. 309 (5735): 728. doi:10.1126/science.309.5735.728. PMID 16051786. S2CID 45532935.

- ↑ Healy, David (1999). The Antidepressant Era. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-674-03958-2.

- ↑ Mant A, Rendle VA, Hall WD, Mitchell PB, Montgomery WS, McManus PR, Hickie IB (October 2004). "Making new choices about antidepressants in Australia: the long view 1975-2002". The Medical Journal of Australia. 181 (7 Suppl): S21–4. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06350.x. PMID 15462638.

- ↑ "Top 10 drugs – 1998". Australian Prescriber. 22: 119. 1999. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- ↑ "Top 10 drugs – 2000–01". Australian Prescriber. 24: 136. 2001. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- ↑ "Prescribing trends for SSRIs and related antidepressants" (PDF). UK MHRA. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- ↑ Skinner BJ, Rovere M (31 July 2007). "Canada's Drug Price Paradox 2007" (PDF). The Fraser Institute. pp. 21–29. Archived from the original on 23 October 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ↑ "Safety review of antidepressants used by children completed". MHRA. 10 December 2003. Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ↑ Boseley, Sarah (10 December 2003). "Drugs for depressed children banned". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2007.

- ↑ "Overview of regulatory status and CSM advice relating to major depressive disorder (MDD) in children and adolescents". MHRA. Archived from the original on 2 August 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2008.

- ↑ Food and Drug Administration (2 May 2007). "FDA Proposes New Warnings About Suicidal Thinking, Behavior in Young Adults Who Take Antidepressant Medications". Archived from the original on 23 February 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ↑ Smith, Aaron (17 July 2006). "Pfizer needs more drugs". CNNMoney.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- ↑ "Bloomberg - Are you a robot?". www.bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1: long volume value

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Wikipedia pages with incorrect protection templates

- Use dmy dates from April 2017

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- World Health Organization essential medicines (alternatives)

- Amines

- Antidepressants

- Chloroarenes

- Dopamine reuptake inhibitors

- Pfizer brands

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

- Sigma antagonists

- Tetralins

- RTT