Diazepam

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /daɪˈæzɪpæm/ |

| Trade names | Valium, Vazepam, Valtoco, others[1] |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | Anxiety, trouble sleeping, agitation[2] |

| Dependence risk | High[5] |

| Addiction risk | Moderate[6][7] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, IM, IV, rectal, nasal spray[3] |

| Defined daily dose | 10 mg[4] |

| Urine detection | Up to 30 days[11] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682047 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 76% (64–97%) by mouth, 81% (62–98%) rectal[9] |

| Metabolism | Liver—CYP2B6 (minor route) to desmethyldiazepam, CYP2C19 (major route) to inactive metabolites, CYP3A4 (major route) to desmethyldiazepam |

| Elimination half-life | (50 hours); 20–100 hours (36–200 hours for main active metabolite desmethyldiazepam)[10][8] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

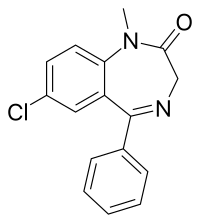

| Formula | C16H13ClN2O |

| Molar mass | 284.74 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Diazepam, first marketed as Valium, is a medicine of the benzodiazepine family that typically produces a calming effect.[12] It is commonly used to treat a range of conditions, including anxiety, seizures, alcohol withdrawal syndrome, benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, muscle spasms, trouble sleeping, and restless legs syndrome.[12] It may also be used to cause memory loss during certain medical procedures.[13][14] It can be taken by mouth, inserted into the rectum, injected into muscle, injected into a vein or used as a nasal spray.[3][14] When given into a vein, effects begin in one to five minutes and last up to an hour.[14] By mouth, effects begin after 15 to 60 minutes.[15]

Common side effects include sleepiness and trouble with coordination.[14][10] Serious side effects are rare.[12] They include suicide, decreased breathing, and an increased risk of seizures if used too frequently in those with epilepsy.[12][14][16] Occasionally, excitement or agitation may occur.[17][18] Long term use can result in tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms on dose reduction.[12] Abrupt stopping after long-term use can be potentially dangerous.[12] After stopping, cognitive problems may persist for six months or longer.[17] It is not recommended during pregnancy or breastfeeding.[14] Its mechanism of action is by increasing the effect of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[17]

Diazepam was patented in 1959 by Hoffmann-La Roche.[12][19][20] It has been one of the most frequently prescribed medications in the world since its launch in 1963.[12] In the United States it was the highest selling medication between 1968 and 1982, selling more than two billion tablets in 1978 alone.[12] In 2017, it was the 135th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than five million prescriptions.[21][22] In 1985 the patent ended, and there are now more than 500 brands available on the market.[12] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines as an alternative to lorazepam.[23] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.01 per dose as of 2015[update].[24] In the United States, it is about US$0.40 per dose.[14]

Medical uses

Diazepam is mainly used to treat anxiety, insomnia, panic attacks and symptoms of acute alcohol withdrawal. It is also used as a premedication for inducing sedation, anxiolysis, or amnesia before certain medical procedures (e.g., endoscopy).[25][26] In 2020, it was approved for use in the United States as a nasal spray to interrupt seizure activity in people with epilepsy.[3][27] Diazepam is the drug of choice for treating benzodiazepine dependence with its long half-life allowing easier dose reduction. Benzodiazepines have a relatively low toxicity in overdose.[17]

Diazepam has a number of uses including:

- Treatment of anxiety, panic attacks, and states of agitation[25][28]

- Treatment of neurovegetative symptoms associated with vertigo[29]

- Treatment of the symptoms of alcohol, opiate, and benzodiazepine withdrawal[25][30]

- Short-term treatment of insomnia[25]

- Treatment of muscle spasms

- Treatment of tetanus, together with other measures of intensive treatment[31]

- Adjunctive treatment of spastic muscular paresis (paraplegia/tetraplegia) caused by cerebral or spinal cord conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, or spinal cord injury (long-term treatment is coupled with other rehabilitative measures)[32]

- Palliative treatment of stiff person syndrome[33]

- Pre- or postoperative sedation, anxiolysis or amnesia (e.g., before endoscopic or surgical procedures)[32]

- Treatment of complications with a hallucinogen crisis and stimulant overdoses and psychosis, such as LSD, cocaine, or methamphetamine[34]

- Preventive treatment of oxygen toxicity during hyperbaric oxygen therapy[35]

Dosages should be determined on an individual basis, depending on the condition being treated, severity of symptoms, patient body weight, and any other conditions the person may have.[34]

Seizures

Intravenous diazepam or lorazepam are first-line treatments for status epilepticus.[17][36] However, intravenous lorazepam has advantages over intravenous diazepam, including a higher rate of terminating seizures and a more prolonged anticonvulsant effect. Diazepam gel was better than placebo gel in reducing the risk of non-cessation of seizures.[37] Diazepam is rarely used for the long-term treatment of epilepsy because tolerance to its anticonvulsant effects usually develops within six to 12 months of treatment, effectively rendering it useless for that purpose.[34][38]

The anticonvulsant effects of diazepam can help in the treatment of seizures due to a drug overdose or chemical toxicity as a result of exposure to sarin, VX, or soman (or other organophosphate poisons), lindane, chloroquine, physostigmine, or pyrethroids.[34][39]

Diazepam is sometimes used intermittently for the prevention of febrile seizures that may occur in children under five years of age.[17] Recurrence rates are reduced, but side effects are common.[40] Long-term use of diazepam for the management of epilepsy is not recommended; however, a subgroup of individuals with treatment-resistant epilepsy benefit from long-term benzodiazepines, and for such individuals, clorazepate has been recommended due to its slower onset of tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects.[17]

Alcohol withdrawal

Because of its relatively long duration of action, and evidence of safety and efficacy, diazepam is preferred over other benzodiazepines for treatment of persons experiencing moderate to severe alcohol withdrawal.[41] An exception to this is when a medication is required intramuscular in which case either lorazepam or midazolam is recommended.[41]

Other

Diazepam is used for the emergency treatment of eclampsia, when IV magnesium sulfate and blood-pressure control measures have failed.[42][43] Benzodiazepines do not have any pain-relieving properties themselves, and are generally recommended to avoid in individuals with pain.[44] However, benzodiazepines such as diazepam can be used for their muscle-relaxant properties to alleviate pain caused by muscle spasms and various dystonias, including blepharospasm.[45][46] Tolerance often develops to the muscle relaxant effects of benzodiazepines such as diazepam.[47] Baclofen[48] or tizanidine is sometimes used as an alternative to diazepam.[medical citation needed]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 10 mg by mouth, by injection, or rectally.[4] Doses in adults; however, range from 2 to 20 mg by mouth and maybe take up to four times per day.[14] Injections may range from 5 to 20 mg per dose.[14]

For trouble sleeping 2 to 5 mg by mouth at night for up to 7 days may be used.[2] For anxiety the dose is often 2.5 to 5 mg twice daily for up to two weeks.[2]

For muscle spasms due to tetanus in babies 0.1 to 0.3 mg/kg by intravenous every one to four hours may be used.[2] For seizures 10 mg by injection or rectally may be used in adults or 0.5 mg/kg may be used in children.[49]

Side effects

Side effects of benzodiazepines such as diazepam include anterograde amnesia, confusion (especially pronounced in higher doses) and sedation. The elderly are more prone to adverse effects of diazepam, such as confusion, amnesia, ataxia, and hangover effects, as well as falls. Long-term use of benzodiazepines such as diazepam is associated with drug tolerance, benzodiazepine dependence, and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome.[17] Like other benzodiazepines, diazepam can impair short-term memory and learning of new information. While benzodiazepine drugs such as diazepam can cause anterograde amnesia, they do not cause retrograde amnesia; information learned before using benzodiazepines is not impaired. Tolerance to the cognitive-impairing effects of benzodiazepines does not tend to develop with long-term use, and the elderly are more sensitive to them.[50] Additionally, after cessation of benzodiazepines, cognitive deficits may persist for at least six months; it is unclear whether these impairments take longer than six months to abate or if they are permanent. Benzodiazepines may also cause or worsen depression.[17] Infusions or repeated intravenous injections of diazepam when managing seizures, for example, may lead to drug toxicity, including respiratory depression, sedation and hypotension. Drug tolerance may also develop to infusions of diazepam if it is given for longer than 24 hours.[17] Sedatives and sleeping pills, including diazepam, have been associated with an increased risk of death.[51]

Diazepam has a range of side effects common to most benzodiazepines, including:

- Suppression of REM sleep and Slow wave sleep

- Impaired motor function

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired balance

- Dizziness

- Reflex tachycardia[52]

Less commonly, paradoxical side effects can occur, including nervousness, irritability, excitement, worsening of seizures, insomnia, muscle cramps, changes in libido, and in some cases, rage and violence. These adverse reactions are more likely to occur in children, the elderly, and individuals with a history of drug or alcohol abuse and or aggression.[17][53][54][55] Diazepam may increase, in some people, the propensity toward self-harming behaviours and, in extreme cases, may provoke suicidal tendencies or acts.[56] Very rarely dystonia can occur.[57]

Diazepam may impair the ability to drive vehicles or operate machinery. The impairment is worsened by consumption of alcohol, because both act as central nervous system depressants.[33]

During the course of therapy, tolerance to the sedative effects usually develops, but not to the anxiolytic and myorelaxant effects.[58]

Patients with severe attacks of apnea during sleep may suffer respiratory depression (hypoventilation), leading to respiratory arrest and death.[medical citation needed]

Diazepam in doses of 5 mg or more causes significant deterioration in alertness performance combined with increased feelings of sleepiness.[59]

Caution

Use of diazepam should be avoided, when possible, in individuals with:[60]

- Ataxia

- Severe hypoventilation

- Acute narrow-angle glaucoma

- Severe liver deficiencies (hepatitis and liver cirrhosis decrease elimination by a factor of two)

- Severe renal deficiencies (for example, patients on dialysis)

- Liver disorders

- Severe sleep apnea

- Severe depression, particularly when accompanied by suicidal tendencies

- Psychosis

- Pregnancy or breast feeding

- Caution required in elderly or debilitated patients

- Coma or shock

- Abrupt discontinuation of therapy

- Acute intoxication with alcohol, narcotics, or other psychoactive substances (with the exception of some hallucinogens or stimulants, where it is occasionally used as a treatment for overdose)

- History of alcohol or drug dependence

- Myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune disorder causing marked fatiguability

- Hypersensitivity or allergy to any drug in the benzodiazepine class

- Benzodiazepine abuse and misuse should be guarded against when prescribed to those with alcohol or drug dependencies or who have psychiatric disorders.[61]

- Pediatric patients

- Less than 18 years of age, this treatment is usually not indicated, except for treatment of epilepsy, and pre- or postoperative treatment. The smallest possible effective dose should be used for this group of patients.[62]

- Under 6 months of age, safety and effectiveness have not been established; diazepam should not be given to those in this age group.[33][62]

- Elderly and very ill patients can possibly suffer apnea or cardiac arrest. Concomitant use of other central nervous system depressants increases this risk. The smallest possible effective dose should be used for this group of people.[62][63] The elderly metabolise benzodiazepines much more slowly than younger adults, and are also more sensitive to the effects of benzodiazepines, even at similar blood plasma levels. Doses of diazepam are recommended to be about half of those given to younger people, and treatment limited to a maximum of two weeks. Long-acting benzodiazepines such as diazepam are not recommended for the elderly.[17] Diazepam can also be dangerous in geriatric patients owing to a significant increased risk of falls.[64]

- Intravenous or intramuscular injections in hypotensive people or those in shock should be administered carefully and vital signs should be monitored.[63]

- Benzodiazepines such as diazepam are lipophilic and rapidly penetrate membranes, so rapidly cross over into the placenta with significant uptake of the drug. Use of benzodiazepines including diazepam in late pregnancy, especially high doses, can result in floppy infant syndrome.[65] Diazepam when taken late in pregnancy, during the third trimester, causes a definite risk of a severe benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome in the neonate with symptoms including hypotonia, and reluctance to suck, to apnoeic spells, cyanosis, and impaired metabolic responses to cold stress. Floppy infant syndrome and sedation in the newborn may also occur. Symptoms of floppy infant syndrome and the neonatal benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome have been reported to persist from hours to months after birth.[66]

Tolerance and dependence

Diazepam, as with other benzodiazepine drugs, can cause tolerance, physical dependence, substance use disorder, and benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Withdrawal from diazepam or other benzodiazepines often leads to withdrawal symptoms similar to those seen during barbiturate or alcohol withdrawal. The higher the dose and the longer the drug is taken, the greater the risk of experiencing unpleasant withdrawal symptoms.[medical citation needed]

Withdrawal symptoms can occur from standard dosages and also after short-term use, and can range from insomnia and anxiety to more serious symptoms, including seizures and psychosis. Withdrawal symptoms can sometimes resemble pre-existing conditions and be misdiagnosed. Diazepam may produce less intense withdrawal symptoms due to its long elimination half-life.[medical citation needed]

Benzodiazepine treatment should be discontinued as soon as possible by a slow and gradual dose reduction regimen.[17][67] Tolerance develops to the therapeutic effects of benzodiazepines; for example tolerance occurs to the anticonvulsant effects and as a result benzodiazepines are not generally recommended for the long-term management of epilepsy. Dose increases may overcome the effects of tolerance, but tolerance may then develop to the higher dose and adverse effects may increase. The mechanism of tolerance to benzodiazepines includes uncoupling of receptor sites, alterations in gene expression, down-regulation of receptor sites, and desensitisation of receptor sites to the effect of GABA. About one-third of individuals who take benzodiazepines for longer than four weeks become dependent and experience withdrawal syndrome on cessation.[17]

Differences in rates of withdrawal (50–100%) vary depending on the patient sample. For example, a random sample of long-term benzodiazepine users typically finds around 50% experience few or no withdrawal symptoms, with the other 50% experiencing notable withdrawal symptoms. Certain select patient groups show a higher rate of notable withdrawal symptoms, up to 100%.[68]

Rebound anxiety, more severe than baseline anxiety, is also a common withdrawal symptom when discontinuing diazepam or other benzodiazepines.[69] Diazepam is therefore only recommended for short-term therapy at the lowest possible dose owing to risks of severe withdrawal problems from low doses even after gradual reduction.[70] The risk of pharmacological dependence on diazepam is significant, and patients experience symptoms of benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome if it is taken for six weeks or longer.[71] In humans, tolerance to the anticonvulsant effects of diazepam occurs frequently.[72]

Improper or excessive use of diazepam can lead to dependence. At a particularly high risk for diazepam misuse, abuse or dependence are:

- People with a history of alcohol or drug abuse or dependence[33][73] Diazepam increases craving for alcohol in problem alcohol consumers. Diazepam also increases the volume of alcohol consumed by problem drinkers.[74]

- People with severe personality disorders, such as borderline personality disorder[75]

Patients from the aforementioned groups should be monitored very closely during therapy for signs of abuse and development of dependence. Therapy should be discontinued if any of these signs are noted, although if dependence has developed, therapy must still be discontinued gradually to avoid severe withdrawal symptoms. Long-term therapy in such instances is not recommended.[33][73]

People suspected of being dependent on benzodiazepine drugs should be very gradually tapered off the drug. Withdrawals can be life-threatening, particularly when excessive doses have been taken for extended periods of time. Equal prudence should be used whether dependence has occurred in therapeutic or recreational contexts.[medical citation needed]

Diazepam is a good choice for tapering for those using high doses of other benzodiazepines since it has a long half-life thus withdrawal symptoms are tolerable.[76] The process is very slow (usually from 14 to 28 weeks) but is considered safe when done appropriately.[77]

Overdose

An individual who has consumed too much diazepam typically displays one or more of these symptoms in a period of approximately four hours immediately following a suspected overdose:[33][78]

- Drowsiness

- Mental confusion

- Hypotension

- Impaired motor functions

- Impaired reflexes

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired balance

- Dizziness

- Coma

Although not usually fatal when taken alone, a diazepam overdose is considered a medical emergency and generally requires the immediate attention of medical personnel. The antidote for an overdose of diazepam (or any other benzodiazepine) is flumazenil (Anexate). This drug is only used in cases with severe respiratory depression or cardiovascular complications. Because flumazenil is a short-acting drug, and the effects of diazepam can last for days, several doses of flumazenil may be necessary. Artificial respiration and stabilization of cardiovascular functions may also be necessary. Though not routinely indicated, activated charcoal can be used for decontamination of the stomach following a diazepam overdose. Emesis is contraindicated. Dialysis is minimally effective. Hypotension may be treated with levarterenol or metaraminol.[33][34][78][79]

The oral LD50 (lethal dose in 50% of the population) of diazepam is 720 mg/kg in mice and 1240 mg/kg in rats.[33] D. J. Greenblatt and colleagues reported in 1978 on two patients who had taken 500 and 2000 mg of diazepam, respectively, went into moderately deep comas, and were discharged within 48 hours without having experienced any important complications, in spite of having high concentrations of diazepam and its metabolites desmethyldiazepam, oxazepam, and temazepam, according to samples taken in the hospital and as follow-up.[80]

Overdoses of diazepam with alcohol, opiates or other depressants may be fatal.[79][81]

Interactions

If diazepam is administered concomitantly with other drugs, attention should be paid to the possible pharmacological interactions. Particular care should be taken with drugs that potentiate the effects of diazepam, such as barbiturates, phenothiazines, opioids, and antidepressants.[33]

Diazepam does not increase or decrease hepatic enzyme activity, and does not alter the metabolism of other compounds. No evidence would suggest diazepam alters its own metabolism with chronic administration.[34]

Agents with an effect on hepatic cytochrome P450 pathways or conjugation can alter the rate of diazepam metabolism. These interactions would be expected to be most significant with long-term diazepam therapy, and their clinical significance is variable.[34]

- Diazepam increases the central depressive effects of alcohol, other hypnotics/sedatives (e.g., barbiturates), other muscle relaxants, certain antidepressants, sedative antihistamines, opioids, and antipsychotics, as well as anticonvulsants such as phenobarbital, phenytoin, and carbamazepine. The euphoriant effects of opioids may be increased, leading to increased risk of psychological dependence.[17][62][82]

- Cimetidine, omeprazole, oxcarbazepine, ticlopidine, topiramate, ketoconazole, itraconazole, disulfiram, fluvoxamine, isoniazid, erythromycin, probenecid, propranolol, imipramine, ciprofloxacin, fluoxetine, and valproic acid prolong the action of diazepam by inhibiting its elimination.[17][34][83]

- Alcohol in combination with diazepam may cause a synergistic enhancement of the hypotensive properties of benzodiazepines and alcohol.[84]

- Oral contraceptives significantly decrease the elimination of desmethyldiazepam, a major metabolite of diazepam.[62][85]

- Rifampin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and phenobarbital increase the metabolism of diazepam, thus decreasing drug levels and effects.[34] Dexamethasone and St John's wort also increase the metabolism of diazepam.[17]

- Diazepam increases the serum levels of phenobarbital.[86]

- Nefazodone can cause increased blood levels of benzodiazepines.[62]

- Cisapride may enhance the absorption, and therefore the sedative activity, of diazepam.[87]

- Small doses of theophylline may inhibit the action of diazepam.[88]

- Diazepam may block the action of levodopa (used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease).[82]

- Diazepam may alter digoxin serum concentrations.[34]

- Other drugs that may have interactions with diazepam include antipsychotics (e.g. chlorpromazine), MAO inhibitors, and ranitidine.[62]

- Because it acts on the GABA receptor, the herb valerian may produce an adverse effect.[89]

- Foods that acidify the urine can lead to faster absorption and elimination of diazepam, reducing drug levels and activity.[82]

- Foods that alkalinize the urine can lead to slower absorption and elimination of diazepam, increasing drug levels and activity.[34]

- Reports conflict as to whether food in general has any effects on the absorption and activity of orally administered diazepam.[82]

Pharmacology

Diazepam is a long-acting "classical" benzodiazepine. Other classical benzodiazepines include chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, nitrazepam, temazepam, flurazepam, bromazepam, and clorazepate.[90] Diazepam has anticonvulsant properties.[91] Benzodiazepines act via micromolar benzodiazepine binding sites as calcium channel blockers and significantly inhibit depolarization-sensitive calcium uptake in rat nerve cell preparations.[92]

Diazepam inhibits acetylcholine release in mouse hippocampal synaptosomes. This has been found by measuring sodium-dependent high-affinity choline uptake in mouse brain cells in vitro, after pretreatment of the mice with diazepam in vivo. This may play a role in explaining diazepam's anticonvulsant properties.[93]

Diazepam binds with high affinity to glial cells in animal cell cultures.[94] Diazepam at high doses has been found to decrease histamine turnover in mouse brain via diazepam's action at the benzodiazepine-GABA receptor complex.[95] Diazepam also decreases prolactin release in rats.[96]

Mechanism of action

Benzodiazepines are positive allosteric modulators of the GABA type A receptors (GABAA). The GABAA receptors are ligand-gated chloride-selective ion channels that are activated by GABA, the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. Binding of benzodiazepines to this receptor complex promotes the binding of GABA, which in turn increases the total conduction of chloride ions across the neuronal cell membrane. This increased chloride ion influx hyperpolarizes the neuron's membrane potential. As a result, the difference between resting potential and threshold potential is increased and firing is less likely. As a result, the arousal of the cortical and limbic systems in the central nervous system is reduced.[1]

The GABAA receptor is a heteromer composed of five subunits, the most common ones being two αs, two βs, and one γ (α2β2γ). For each subunit, many subtypes exist (α1–6, β1–3, and γ1–3). GABAA receptors containing the α1 subunit mediate the sedative, the anterograde amnesic, and partly the anticonvulsive effects of diazepam. GABAA receptors containing α2 mediate the anxiolytic actions and to a large degree the myorelaxant effects. GABAA receptors containing α3 and α5 also contribute to benzodiazepines myorelaxant actions, whereas GABAA receptors comprising the α5 subunit were shown to modulate the temporal and spatial memory effects of benzodiazepines.[97] Diazepam is not the only drug to target these GABAA receptors. Drugs such as flumazenil also bind to GABAA to induce their effects.[98]

Diazepam appears to act on areas of the limbic system, thalamus, and hypothalamus, inducing anxiolytic effects. Benzodiazepine drugs including diazepam increase the inhibitory processes in the cerebral cortex.[99]

The anticonvulsant properties of diazepam and other benzodiazepines may be in part or entirely due to binding to voltage-dependent sodium channels rather than benzodiazepine receptors. Sustained repetitive firing seems limited by benzodiazepines' effect of slowing recovery of sodium channels from inactivation.[100]

The muscle relaxant properties of diazepam are produced via inhibition of polysynaptic pathways in the spinal cord.[101]

Pharmacokinetics

Diazepam can be administered orally, intravenously (must be diluted, as it is painful and damaging to veins), intramuscularly (IM), or as a suppository.[34]

The onset of action is one to five minutes for IV administration and 15–30 minutes for IM administration. The duration of diazepam's peak pharmacological effects is 15 minutes to one hour for both routes of administration.[52] The bioavailability after oral administration is 100%, and 90% after rectal administration. The half-life of diazepam in general is 30–56 hours.[1] Peak plasma levels occur between 30 and 90 minutes after oral administration and between 30 and 60 minutes after intramuscular administration; after rectal administration, peak plasma levels occur after 10 to 45 minutes. Diazepam is highly protein-bound, with 96 to 99% of the absorbed drug being protein-bound. The distribution half-life of diazepam is two to 13 minutes.[17]

Diazepam is highly lipid-soluble, and is widely distributed throughout the body after administration. It easily crosses both the blood–brain barrier and the placenta, and is excreted into breast milk. After absorption, diazepam is redistributed into muscle and adipose tissue. Continual daily doses of diazepam quickly build to a high concentration in the body (mainly in adipose tissue), far in excess of the actual dose for any given day.[17][34]

Diazepam is stored preferentially in some organs, including the heart. Absorption by any administered route and the risk of accumulation is significantly increased in the neonate, and withdrawal of diazepam during pregnancy and breast feeding is clinically justified.[102]

Diazepam undergoes oxidative metabolism by demethylation (CYP 2C9, 2C19, 2B6, 3A4, and 3A5), hydroxylation (CYP 3A4 and 2C19) and glucuronidation in the liver as part of the cytochrome P450 enzyme system. It has several pharmacologically active metabolites. The main active metabolite of diazepam is desmethyldiazepam (also known as nordazepam or nordiazepam). Its other active metabolites include the minor active metabolites temazepam and oxazepam. These metabolites are conjugated with glucuronide, and are excreted primarily in the urine. Because of these active metabolites, the serum values of diazepam alone are not useful in predicting the effects of the drug. Diazepam has a biphasic half-life of about one to three days, and two to seven days for the active metabolite desmethyldiazepam.[17] Most of the drug is metabolised; very little diazepam is excreted unchanged.[34] The elimination half-life of diazepam and also the active metabolite desmethyldiazepam increases significantly in the elderly, which may result in prolonged action, as well as accumulation of the drug during repeated administration.[103]

Chemisty

Diazepam is a 1,4-benzodiazepine.[1] Diazepam occurs as solid white or yellow crystals with a melting point of 131.5 to 134.5 °C. It is odorless, and has a slightly bitter taste. The British Pharmacopoeia lists it as being very slightly soluble in water, soluble in alcohol, and freely soluble in chloroform. The United States Pharmacopoeia lists diazepam as soluble 1 in 16 ethyl alcohol, 1 in 2 of chloroform, 1 in 39 ether, and practically insoluble in water. The pH of diazepam is neutral (i.e., pH = 7). Due to additives such as benzoic acid/benzoate in the injectable form.[clarification needed] (Plumb's, 6th edition page 372) Diazepam has a shelf life of five years for oral tablets and three years for IV/IM solutions.[34] Diazepam should be stored at room temperature (15–30 °C). The solution for parenteral injection should be protected from light and kept from freezing. The oral forms should be stored in air-tight containers and protected from light.[83]

Diazepam can absorb into plastics, so liquid preparations should not be kept in plastic bottles or syringes, etc. As such, it can leach into the plastic bags and tubing used for intravenous infusions. Absorption appears to depend on several factors, such as temperature, concentration, flow rates, and tube length. Diazepam should not be administered if a precipitate has formed and does not dissolve.[83]

Detection in body fluids

Diazepam may be quantified in blood or plasma to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, provide evidence in an impaired driving arrest, or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Blood or plasma diazepam concentrations are usually in a range of 0.1–1.0 mg/l in persons receiving the drug therapeutically. Most commercial immunoassays for the benzodiazepine class of drugs cross-react with diazepam, but confirmation and quantitation are usually performed using chromatographic techniques.[104][105][106]

History

Diazepam was the second benzodiazepine invented by Leo Sternbach of Hoffmann-La Roche at the company's Nutley, New Jersey, facility[107] following chlordiazepoxide (Librium), which was approved for use in 1960. Released in 1963 as an improved version of Librium, diazepam became incredibly popular, helping Roche to become a pharmaceutical industry giant. It is 2.5 times more potent than its predecessor, which it quickly surpassed in terms of sales. After this initial success, other pharmaceutical companies began to introduce other benzodiazepine derivatives.[108]

The benzodiazepines gained popularity among medical professionals as an improvement over barbiturates, which have a comparatively narrow therapeutic index, and are far more sedative at therapeutic doses. The benzodiazepines are also far less dangerous; death rarely results from diazepam overdose, except in cases where it is consumed with large amounts of other depressants (such as alcohol or opioids).[79] Benzodiazepine drugs such as diazepam initially had widespread public support, but with time the view changed to one of growing criticism and calls for restrictions on their prescription.[109]

Marketed by Roche using an advertising campaign conceived by the William Douglas McAdams Agency under the leadership of Arthur Sackler,[110] diazepam was the top-selling pharmaceutical in the United States from 1969 to 1982, with peak annual sales in 1978 of 2.3 billion tablets.[108] Diazepam, along with oxazepam, nitrazepam and temazepam, represents 82% of the benzodiazepine market in Australia.[111] While psychiatrists continue to prescribe diazepam for the short-term relief of anxiety, neurology has taken the lead in prescribing diazepam for the palliative treatment of certain types of epilepsy and spastic activity, for example, forms of paresis. It is also the first line of defense for a rare disorder called stiff-person syndrome.[32]

Society and culture

Cost

The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.01 per dose as of 2015[update].[24] In the United States, it is about US$0.40 per dose.[14]

-

Diazepam costs (US)

-

Diazepam prescriptions (US)

Availability

Diazepam is marketed in over 500 brands throughout the world.[112] It is supplied in oral, injectable, inhalation, and rectal forms.[34][83][113]

The United States military employs a specialized diazepam preparation known as Convulsive Antidote, Nerve Agent (CANA), which contains diazepam. One CANA kit is typically issued to service members, along with three Mark I NAAK kits, when operating in circumstances where chemical weapons in the form of nerve agents are considered a potential hazard. Both of these kits deliver drugs using autoinjectors. They are intended for use in "buddy aid" or "self aid" administration of the drugs in the field prior to decontamination and delivery of the patient to definitive medical care.[114]

Recreational use

Diazepam is a drug of potential abuse and can cause drug dependence. Urgent action by national governments has been recommended to improve prescribing patterns of benzodiazepines such as diazepam.[115][116] A single dose of diazepam modulates the dopamine system in similar ways to how morphine and alcohol modulate the dopaminergic pathways.[117] Between 50 and 64% of rats will self-administer diazepam.[118] Diazepam has been shown to be able to substitute for the behavioural effects of barbiturates in a primate study.[119] Diazepam has been found as an adulterant in heroin.[120]

Diazepam drug misuse can occur either through recreational misuse where the drug is taken to achieve a high or when the drug is continued long term against medical advice.[121]

Sometimes, it is used by stimulant users to "come down" and sleep and to help control the urge to binge. These users often escalate dosage from 2 to 25 times the therapeutic dose of 5 to 10 mg.[122]

A large-scale study in the US, conducted by SAMHSA, using data from 2011, determined benzodiazepines were present in 28.7% of emergency department visits involving nonmedical use of pharmaceuticals. In this regard, benzodiazepines are second only to opiates, the study found in 39.2% of visits. About 29.3% of drug-related suicide attempts involve benzodiazepines, making them the most frequently represented class in drug-related suicide attempts. Males abuse benzodiazepines as commonly as females.[123]

Benzodiazepines, including diazepam, nitrazepam, and flunitrazepam, account for the largest volume of forged drug prescriptions in Sweden, a total of 52% of drug forgeries being for benzodiazepines.[124]

Diazepam was detected in 26% of cases of people suspected of driving under the influence of drugs in Sweden, and its active metabolite nordazepam was detected in 28% of cases. Other benzodiazepines and zolpidem and zopiclone also were found in high numbers. Many drivers had blood levels far exceeding the therapeutic dose range, suggesting a high degree of abuse potential for benzodiazepines and zolpidem and zopiclone.[104] In Northern Ireland, in cases where drugs were detected in samples from impaired drivers who were not impaired by alcohol, benzodiazepines were found in 87% of cases. Diazepam was the most commonly detected benzodiazepine.[125]

Legal status

Diazepam is regulated in most countries as a prescription drug:

International

Diazepam is a Schedule IV controlled drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[126]

UK

Classified as a controlled drug, listed under Schedule IV, Part I (CD Benz POM) of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001, allowing possession with a valid prescription. The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 makes it illegal to possess the drug without a prescription, and for such purposes it is classified as a Class C drug.[127]

Germany

Classified as a prescription drug, or in high dosage as a restricted drug (Betäubungsmittelgesetz, Anlage III).[128]

Australia

Diazepam is Schedule 4 substance under the Poisons Standard (June 2018).[129] A schedule 4 drug is outlined in the Poisons Act 1964 as, "Substances, the use or supply of which should be by or on the order of persons permitted by State or Territory legislation to prescribe and should be available from a pharmacist on prescription." [129]

United States

Diazepam is controlled as a Schedule IV substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970.[medical citation needed]

Judicial executions

The states of California and Florida offer diazepam to condemned inmates as a pre-execution sedative as part of their lethal injection program, although the state of California has not executed a prisoner since 2006.[130][131] In August 2018, Nebraska used diazepam as part of the drug combination used to execute the first death row inmate executed in Nebraska in over 21 years.[132]

Veterinary uses

Diazepam is used as a short-term sedative and anxiolytic for cats and dogs,[133] sometimes used as an appetite stimulant.[133][134] It can also be used to stop seizures in dogs and cats.[135]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 "National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Drugs and Human Performance Fact Sheet- Diazepam". Archived from the original on 2017-03-27. Retrieved 2017-11-13.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "DIAZEPAM oral - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2020. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "MSF2020" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Valtoco- diazepam spray". DailyMed. 13 January 2020. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ↑ Edmunds, Marilyn; Mayhew, Maren (17 April 2013). Pharmacology for the Primary Care Provider (4th ed.). Mosby. p. 545. ISBN 9780323087902. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ Clinical Addiction Psychiatry. Cambridge University Press. 2010. p. 156. ISBN 9781139491693. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ Ries, Richard K. (2009). Principles of addiction medicine (4 ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 106. ISBN 9780781774772. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Diazepam Tablets BP 10mg - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 16 September 2019. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ↑ Dhillon S, Oxley J, Richens A (March 1982). "Bioavailability of diazepam after intravenous, oral and rectal administration in adult epileptic patients". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 13 (3): 427–32. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1982.tb01397.x. PMC 1402110. PMID 7059446.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Valium- diazepam tablet". DailyMed. 8 November 2019. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- ↑ "Interpreting Urine Drug Tests (UDT)". Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 12.9 Calcaterra NE, Barrow JC (April 2014). "Classics in chemical neuroscience: diazepam (valium)". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 5 (4): 253–60. doi:10.1021/cn5000056. PMC 3990949. PMID 24552479.

- ↑ "Diazepam". PubChem. National Institute of Health: National Library of Medicine. 2006. Archived from the original on 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2006-03-11.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 14.9 "Diazepam". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2015-06-05.

- ↑ Dhaliwal JS, Saadabadi A (2019). "Diazepam". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30725707. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- ↑ Dodds TJ (March 2017). "Prescribed Benzodiazepines and Suicide Risk: A Review of the Literature". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 19 (2). doi:10.4088/PCC.16r02037. PMID 28257172.

- ↑ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 17.10 17.11 17.12 17.13 17.14 17.15 17.16 17.17 17.18 17.19 Riss J, Cloyd J, Gates J, Collins S (August 2008). "Benzodiazepines in epilepsy: pharmacology and pharmacokinetics". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 118 (2): 69–86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01004.x. PMID 18384456.

- ↑ Perkin, Ronald M. (2008). Pediatric hospital medicine : textbook of inpatient management (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 862. ISBN 9780781770323. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 535. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ US patent 3371085, Leo Henryk Sternbach & Earl Reeder, "5-ARYL-3H-1,4-BENZODIAZEPIN-2(1H)-ONES", published 1968-02-27, issued 1968-02-27, assigned to Hoffmann La Roche AG

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ "Diazepam - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "Diazepam". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2015.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 "Drug Bank – Diazepam". Archived from the original on December 24, 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Bråthen G, Ben-Menachem E, Brodtkorb E, Galvin R, Garcia-Monco JC, Halasz P, et al. (August 2005). "EFNS guideline on the diagnosis and management of alcohol-related seizures: report of an EFNS task force". European Journal of Neurology. 12 (8): 575–81. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01247.x. PMID 16053464.

- ↑ "FDA approves Valtoco". Drugs.com. 13 January 2020. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ↑ "Valium Tablets". NPS MedicineWise. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 2019-08-29.

- ↑ Cesarani A, Alpini D, Monti B, Raponi G (March 2004). "The treatment of acute vertigo". Neurological Sciences. 25 Suppl 1: S26-30. doi:10.1007/s10072-004-0213-8. PMID 15045617. S2CID 25105327.

- ↑ Lader M, Tylee A, Donoghue J (2009). "Withdrawing benzodiazepines in primary care". CNS Drugs. 23 (1): 19–34. doi:10.2165/0023210-200923010-00002. PMID 19062773. S2CID 113206.

- ↑ Okoromah CN, Lesi FE (2004). Okoromah CA (ed.). "Diazepam for treating tetanus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003954. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003954.pub2. PMID 14974046.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "Diazepam: indications". Rxlist.com. RxList Inc. January 24, 2005. Archived from the original on February 16, 2006. Retrieved March 11, 2006.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 33.8 Thomson Healthcare (Micromedex) (March 2000). "Diazepam". Prescription Drug Information. Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2006-06-19. Retrieved 2006-03-11.

- ↑ 34.00 34.01 34.02 34.03 34.04 34.05 34.06 34.07 34.08 34.09 34.10 34.11 34.12 34.13 34.14 34.15 Munne P (1998). Ruse M (ed.). "Diazepam". Inchem.org. Inchem.org. Archived from the original on 2006-02-27. Retrieved 2006-03-11.

- ↑ Kindwall, Eric P.; Whelan, Harry T. (1999). Hyperbaric Medicine Practice (2nd ed.). Best Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-941332-78-1.

- ↑ Walker M (September 2005). "Status epilepticus: an evidence based guide". BMJ. 331 (7518): 673–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7518.673. PMC 1226249. PMID 16179702.

- ↑ Prasad M, Krishnan PR, Sequeira R, Al-Roomi K (September 2014). "Anticonvulsant therapy for status epilepticus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD003723. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003723.pub3. PMC 7154380. PMID 25207925.

- ↑ Isojärvi JI, Tokola RA (December 1998). "Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy in people with intellectual disability". Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 42 Suppl 1: 80–92. PMID 10030438.

- ↑ Bajgar J (2004). Organophosphates/nerve agent poisoning: mechanism of action, diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment. Advances in Clinical Chemistry. Vol. 38. pp. 151–216. doi:10.1016/S0065-2423(04)38006-6. ISBN 978-0-12-010338-6. PMID 15521192.

- ↑ Offringa M, Newton R, Cozijnsen MA, Nevitt SJ (February 2017). "Prophylactic drug management for febrile seizures in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD003031. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003031.pub3. PMC 6464693. PMID 28225210. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Weintraub SJ (February 2017). "Diazepam in the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Alcohol Withdrawal". CNS Drugs. 31 (2): 87–95. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0403-y. PMID 28101764. S2CID 42610220.

- ↑ Kaplan PW (November 2004). "Neurologic aspects of eclampsia". Neurologic Clinics. 22 (4): 841–61. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2004.07.005. PMID 15474770.

- ↑ Duley L (February 2005). "Evidence and practice: the magnesium sulphate story". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 19 (1): 57–74. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2004.10.010. PMID 15749066.

- ↑ Zeilhofer HU, Witschi R, Hösl K (May 2009). "Subtype-selective GABAA receptor mimetics--novel antihyperalgesic agents?" (PDF). Journal of Molecular Medicine. 87 (5): 465–9. doi:10.1007/s00109-009-0454-3. hdl:20.500.11850/20278. PMID 19259638. S2CID 5614111. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ Mezaki T, Hayashi A, Nakase H, Hasegawa K (September 2005). "[Therapy of dystonia in Japan]". Rinsho Shinkeigaku = Clinical Neurology (in Japanese). 45 (9): 634–42. PMID 16248394.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Kachi T (December 2001). "[Medical treatment of dystonia]". Rinsho Shinkeigaku = Clinical Neurology (in Japanese). 41 (12): 1181–2. PMID 12235832.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Ashton H (May 2005). "The diagnosis and management of benzodiazepine dependence" (PDF). Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 18 (3): 249–55. doi:10.1097/01.yco.0000165594.60434.84. PMID 16639148. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ Mañon-Espaillat R, Mandel S (January 1999). "Diagnostic algorithms for neuromuscular diseases". Clinics in Podiatric Medicine and Surgery. 16 (1): 67–79. PMID 9929772.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Yudofsky SC, Hales RE (1 December 2007). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Neuropsychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Press Textbook of Neuropsychiatry). US: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. pp. 583–584. ISBN 978-1-58562-239-9. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016.

- ↑ Kripke DF (February 2016). "Mortality Risk of Hypnotics: Strengths and Limits of Evidence" (PDF). Drug Safety. 39 (2): 93–107. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0362-0. PMID 26563222. S2CID 7946506. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Langsam, Yedidyah. "DIAZEPAM (VALIUM AND OTHERS)". Brooklyn College (Eilat.sci.Brooklyn.CUNY.edu). Archived from the original on 2007-07-30. Retrieved 2006-03-23.

- ↑ Marrosu F, Marrosu G, Rachel MG, Biggio G (1987). "Paradoxical reactions elicited by diazepam in children with classic autism". Functional Neurology. 2 (3): 355–61. PMID 2826308.

- ↑ "Diazepam: Side Effects". RxList.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2006. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ↑ Michel L, Lang JP (2003). "[Benzodiazepines and forensic aspects]". L'Encephale (in French). 29 (6): 479–85. PMID 15029082. Archived from the original on 2007-11-27.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Berman ME, Jones GD, McCloskey MS (February 2005). "The effects of diazepam on human self-aggressive behavior". Psychopharmacology. 178 (1): 100–6. doi:10.1007/s00213-004-1966-8. PMID 15316710. S2CID 20629702.

- ↑ Pérez Trullen JM, Modrego Pardo PJ, Vázquez André M, López Lozano JJ (1992). "Bromazepam-induced dystonia". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & Pharmacotherapie. 46 (8): 375–6. doi:10.1016/0753-3322(92)90306-R. PMID 1292648.

- ↑ Hriscu A, Gherase F, Năstasă V, Hriscu E (October–December 2002). "[An experimental study of tolerance to benzodiazepines]". Revista Medico-Chirurgicala a Societatii de Medici Si Naturalisti Din Iasi. 106 (4): 806–11. PMID 14974234.

- ↑ Kozená L, Frantik E, Horváth M (May 1995). "Vigilance impairment after a single dose of benzodiazepines". Psychopharmacology. 119 (1): 39–45. doi:10.1007/BF02246052. PMID 7675948. S2CID 2618084.

- ↑ Epocrates. "Diazepam Contraindications and Cautions". US: Epocrates Online. Archived from the original on 10 July 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

- ↑ Authier N, Balayssac D, Sautereau M, Zangarelli A, Courty P, Somogyi AA, et al. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Francaises. 67 (6): 408–13. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 62.4 62.5 62.6 "Diazepam". PDRHealth.com. PDRHealth.com. 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-01-17. Retrieved 2006-03-10.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 "Diazepam: precautions". Rxlist.com. RxList Inc. January 24, 2005. Archived from the original on April 7, 2006. Retrieved March 10, 2006.

- ↑ Shats V, Kozacov S (June 1995). "[Falls in the geriatric department: responsibility of the care-giver and the hospital]". Harefuah (in Hebrew). 128 (11): 690–3, 743. PMID 7557666.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Kanto JH (May 1982). "Use of benzodiazepines during pregnancy, labour and lactation, with particular reference to pharmacokinetic considerations". Drugs. 23 (5): 354–80. doi:10.2165/00003495-198223050-00002. PMID 6124415. S2CID 27014006.

- ↑ McElhatton PR (1994). "The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation". Reproductive Toxicology. 8 (6): 461–75. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9. PMID 7881198.

- ↑ MacKinnon GL, Parker WA (1982). "Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome: a literature review and evaluation". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 9 (1): 19–33. doi:10.3109/00952998209002608. PMID 6133446.

- ↑ Onyett SR (April 1989). "The benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome and its management". The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 39 (321): 160–3. PMC 1711840. PMID 2576073.

- ↑ Chouinard G, Labonte A, Fontaine R, Annable L (1983). "New concepts in benzodiazepine therapy: rebound anxiety and new indications for the more potent benzodiazepines". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 7 (4–6): 669–73. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(83)90043-X. PMID 6141609. S2CID 32967696.

- ↑ Lader M (December 1987). "Long-term anxiolytic therapy: the issue of drug withdrawal". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 48 Suppl: 12–6. PMID 2891684.

- ↑ Murphy SM, Owen R, Tyrer P (April 1989). "Comparative assessment of efficacy and withdrawal symptoms after 6 and 12 weeks' treatment with diazepam or buspirone". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 154 (4): 529–34. doi:10.1192/bjp.154.4.529. PMID 2686797. S2CID 5024826.

- ↑ Loiseau P (1983). "[Benzodiazepines in the treatment of epilepsy]". L'Encephale. 9 (4 Suppl 2): 287B–292B. PMID 6373234.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 "Diazepam: abuse and dependence". Rxlist.com. RxList Inc. January 24, 2005. Archived from the original on February 16, 2006. Retrieved March 10, 2006.

- ↑ Poulos CX, Zack M (November 2004). "Low-dose diazepam primes motivation for alcohol and alcohol-related semantic networks in problem drinkers". Behavioural Pharmacology. 15 (7): 503–12. doi:10.1097/00008877-200411000-00006. PMID 15472572.

- ↑ Vorma H, Naukkarinen HH, Sarna SJ, Kuoppasalmi KI (2005). "Predictors of benzodiazepine discontinuation in subjects manifesting complicated dependence". Substance Use & Misuse. 40 (4): 499–510. doi:10.1081/JA-200052433. PMID 15830732. S2CID 1366333.

- ↑ Thirtala, Thripura; Kaur, Kanwaldeep; Karlapati, Surya Kumar; Lippmann, Steven (July 2013). "Consider this slow-taper program for benzodiazepines". Current Psychiatry. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ "Tapering Benzodiazepines" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 "Diazepam: overdose". Rxlist.com. RxList Inc. January 24, 2005. Archived from the original on February 16, 2006. Retrieved March 10, 2006.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 Barondes SH (2003). Better Than Prozac. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 47–59. ISBN 978-0-19-515130-5.

- ↑ Greenblatt DJ, Woo E, Allen MD, Orsulak PJ, Shader RI (October 1978). "Rapid recovery from massive diazepam overdose". JAMA. 240 (17): 1872–4. doi:10.1001/jama.1978.03290170054026. PMID 357765.

- ↑ Lai SH, Yao YJ, Lo DS (October 2006). "A survey of buprenorphine related deaths in Singapore". Forensic Science International. 162 (1–3): 80–6. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.03.037. PMID 16879940.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 Holt, Gary A. (1998). Food and Drug Interactions: A Guide for Consumers. Chicago: Precept Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-944496-59-6.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 83.3 Mikota, Susan K.; Plumb, Donald C. (2005). "Diazepam". The Elephant Formulary. Elephant Care International. Archived from the original on 2005-09-08.

- ↑ Zácková P, Kvĕtina J, Nĕmec J, Nĕmcová J (December 1982). "Cardiovascular effects of diazepam and nitrazepam in combination with ethanol". Die Pharmazie. 37 (12): 853–6. PMID 7163374.

- ↑ Back DJ, Orme ML (June 1990). "Pharmacokinetic drug interactions with oral contraceptives". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 18 (6): 472–84. doi:10.2165/00003088-199018060-00004. PMID 2191822. S2CID 32523973.

- ↑ Bendarzewska-Nawrocka B, Pietruszewska E, Stepień L, Bidziński J, Bacia T (January–February 1980). "[Relationship between blood serum luminal and diphenylhydantoin level and the results of treatment and other clinical data in drug-resistant epilepsy]". Neurologia I Neurochirurgia Polska. 14 (1): 39–45. PMID 7374896.

- ↑ Bateman DN (1986). "The action of cisapride on gastric emptying and the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of oral diazepam". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 30 (2): 205–8. doi:10.1007/BF00614304. PMID 3709647. S2CID 41495586.

- ↑ Mattila MJ, Nuotto E (1983). "Caffeine and theophylline counteract diazepam effects in man". Medical Biology. 61 (6): 337–43. PMID 6374311.

- ↑ "Possible Interactions with: Valerian". University of Maryland Medical Center. May 13, 2013. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ↑ Braestrup C, Squires RF (April 1978). "Pharmacological characterization of benzodiazepine receptors in the brain". European Journal of Pharmacology. 48 (3): 263–70. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(78)90085-7. PMID 639854.

- ↑ Chweh AY, Swinyard EA, Wolf HH, Kupferberg HJ (February 1985). "Effect of GABA agonists on the neurotoxicity and anticonvulsant activity of benzodiazepines". Life Sciences. 36 (8): 737–44. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(85)90193-6. PMID 2983169.

- ↑ Taft WC, DeLorenzo RJ (May 1984). "Micromolar-affinity benzodiazepine receptors regulate voltage-sensitive calcium channels in nerve terminal preparations" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PDF). 81 (10): 3118–22. Bibcode:1984PNAS...81.3118T. doi:10.1073/pnas.81.10.3118. PMC 345232. PMID 6328498. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-06-25.

- ↑ Miller JA, Richter JA (January 1985). "Effects of anticonvulsants in vivo on high affinity choline uptake in vitro in mouse hippocampal synaptosomes". British Journal of Pharmacology. 84 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb17368.x. PMC 1987204. PMID 3978310.

- ↑ Gallager DW, Mallorga P, Oertel W, Henneberry R, Tallman J (February 1981). "[3H]Diazepam binding in mammalian central nervous system: a pharmacological characterization". The Journal of Neuroscience. 1 (2): 218–25. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.01-02-00218.1981. PMC 6564145. PMID 6267221.

- ↑ Oishi R, Nishibori M, Itoh Y, Saeki K (May 1986). "Diazepam-induced decrease in histamine turnover in mouse brain". European Journal of Pharmacology. 124 (3): 337–42. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(86)90236-0. PMID 3089825.

- ↑ Grandison L (1982). "Suppression of prolactin secretion by benzodiazepines in vivo". Neuroendocrinology. 34 (5): 369–73. doi:10.1159/000123330. PMID 6979001.

- ↑ Tan, Kelly R.; Rudolph, Uwe; Lüscher, Christian (2011). "Hooked on benzodiazepines: GABAA receptor subtypes and addiction" (PDF). University of Geneva. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ↑ Whirl-Carrillo M, McDonagh EM, Hebert JM, Gong L, Sangkuhl K, Thorn CF, et al. (October 2012). "Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 92 (4): 414–7. doi:10.1038/clpt.2012.96. PMC 3660037. PMID 22992668.

- ↑ Zakusov VV, Ostrovskaya RU, Kozhechkin SN, Markovich VV, Molodavkin GM, Voronina TA (October 1977). "Further evidence for GABA-ergic mechanisms in the action of benzodiazepines". Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie. 229 (2): 313–26. PMID 23084.

- ↑ McLean MJ, Macdonald RL (February 1988). "Benzodiazepines, but not beta-carbolines, limit high-frequency repetitive firing of action potentials of spinal cord neurons in cell culture". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 244 (2): 789–95. PMID 2450203.

- ↑ Date SK, Hemavathi KG, Gulati OD (November 1984). "Investigation of the muscle relaxant activity of nitrazepam". Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie. 272 (1): 129–39. PMID 6517646.

- ↑ Olive G, Dreux C (January 1977). "[Pharmacologic bases of use of benzodiazepines in peréinatal medicine]". Archives Francaises de Pediatrie. 34 (1): 74–89. PMID 851373.

- ↑ Vozeh S (November 1981). "[Pharmacokinetic of benzodiazepines in old age]". Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift. 111 (47): 1789–93. PMID 6118950.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Jones AW, Holmgren A, Kugelberg FC (April 2007). "Concentrations of scheduled prescription drugs in blood of impaired drivers: considerations for interpreting the results". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 29 (2): 248–60. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803d3c04. PMID 17417081. S2CID 25511804.

- ↑ Fraser AD, Bryan W (1991). "Evaluation of the Abbott ADx and TDx serum benzodiazepine immunoassays for analysis of alprazolam". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 15 (2): 63–5. doi:10.1093/jat/15.2.63. PMID 1675703.

- ↑ Baselt R (2011). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (9th ed.). Seal Beach, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 471–473. ISBN 978-0-9626523-8-7.

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (June 26, 2012). "Roche to Shut Former U.S. Headquarters". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Sample I (October 3, 2005). "Leo Sternbach's Obituary". The Guardian (Guardian Unlimited). Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 2006-03-10.

- ↑ Marshall KP, Georgievskava Z, Georgievsky I (June 2009). "Social reactions to Valium and Prozac: a cultural lag perspective of drug diffusion and adoption". Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy. 5 (2): 94–107. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2008.06.005. PMID 19524858.

- ↑ "How the American opiate epidemic was started by one pharmaceutical company". Theweek.com. 4 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ↑ Mant A, Whicker SD, McManus P, Birkett DJ, Edmonds D, Dumbrell D (December 1993). "Benzodiazepine utilisation in Australia: report from a new pharmacoepidemiological database". Australian Journal of Public Health. 17 (4): 345–9. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.1993.tb00167.x. PMID 7911332.

- ↑ "International AED Database". ILAE. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ↑ "Delivery of diazepam through an inhalation route". US Patent 6,805,853. PharmCast.com. October 19, 2004. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ↑ U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense, Medical Management of Chemical Casualties Handbook, Third Edition (June 2000), Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD, pp. 118–126.

- ↑ Atack JR (May 2005). "The benzodiazepine binding site of GABA(A) receptors as a target for the development of novel anxiolytics". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 14 (5): 601–18. doi:10.1517/13543784.14.5.601. PMID 15926867.

- ↑ Dièye AM, Sylla M, Ndiaye A, Ndiaye M, Sy GY, Faye B (June 2006). "Benzodiazepines prescription in Dakar: a study about prescribing habits and knowledge in general practitioners, neurologists and psychiatrists". Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 20 (3): 235–8. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2006.00400.x. PMID 16671957.

- ↑ "New Evidence on Addiction To Medicines Diazepam Has Effect on Nerve Cells in the Brain Reward System". Medical News Today. August 2008. Archived from the original on September 12, 2008. Retrieved September 25, 2008.

- ↑ Yoshimura K, Horiuchi M, Inoue Y, Yamamoto K (January 1984). "[Pharmacological studies on drug dependence. (III): Intravenous self-administration of some CNS-affecting drugs and a new sleep-inducer, 1H-1, 2, 4-triazolyl benzophenone derivative (450191-S), in rats]". Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. Folia Pharmacologica Japonica. 83 (1): 39–67. doi:10.1254/fpj.83.39. PMID 6538866.

- ↑ Woolverton WL, Nader MA (December 1995). "Effects of several benzodiazepines, alone and in combination with flumazenil, in rhesus monkeys trained to discriminate pentobarbital from saline". Psychopharmacology. 122 (3): 230–6. doi:10.1007/BF02246544. PMID 8748392. S2CID 24836734.

- ↑ "Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 1996" (PDF). United Nations. International Narcotics Control Board. 1996. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

Phenobarbital was identified as the psychotropic substance most frequently used as an adulterant in seized heroin; it was followed by diazepam and flunitrazepam.

- ↑ Griffiths RR, Johnson MW (2005). "Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 66 Suppl 9: 31–41. PMID 16336040.

- ↑ Overclocker. "Methamphetamine and Benzodiazepines: Methamphetamine & Benzodiazepines". Erowid Experience Vaults. Archived from the original on 18 December 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2011). "Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits". Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ Bergman U, Dahl-Puustinen ML (1989). "Use of prescription forgeries in a drug abuse surveillance network". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 36 (6): 621–3. doi:10.1007/BF00637747. PMID 2776820.

- ↑ Cosbey SH (December 1986). "Drugs and the impaired driver in Northern Ireland: an analytical survey". Forensic Science International. 32 (4): 245–58. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(86)90201-X. PMID 3804143.

- ↑ International Narcotics Control Board (2003). "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). Green list. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-13. Retrieved 2014-12-12.

- ↑ "List of Controlled Drugs". Archived from the original on 2011-12-30.

- ↑ "Anlage III (zu § 1 Abs. 1) verkehrsfähige und verschreibungsfähige Betäubungsmittel". Betäubungsmittelgesetz. 2001. Archived from the original on 2010-01-03. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 Poisons Standard June 2018 "Poisons Standard June 2018". Archived from the original on 2016-01-19. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- ↑ San Quentin State Prison Operational Procedure 0–770, Execution By Lethal Injection (pp. 44 & 92) Archived 2008-06-25 at the Wayback Machine Accessed January 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Execution by lethal injection procedures" (PDF). Florida Department of Corrections. 9 September 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Nebraska executes Carey Dean Moore for murders of Omaha cab drivers Maynard Helgeland, Reuel Van Ness Jr". Lincoln Journal Star. August 14, 2018. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ↑ 133.0 133.1 "Drugs Affecting Appetite (Monogastric)". The Merck Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on 2012-10-28. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- ↑ Rahminiwati M, Nishimura M (April 1999). "Effects of delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol and diazepam on feeding behavior in mice". The Journal of Veterinary Medical Science. 61 (4): 351–5. doi:10.1292/jvms.61.351. PMID 10342284.

- ↑ Shell, Linda (March 2012). "Anticonvulsants Used to Stop Ongoing Seizure Activity". Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

Dogs and Cats:

A variety of drugs can be used to stop seizures in dogs and cats.

Benzodiazepines:

Diazepam is the most common benzodiazepine used in dogs and cats to reduce motor activity and permit placement of an IV catheter.

Further reading

- Dean L (2016). "Diazepam Therapy and CYP2C19 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520370. Bookshelf ID: NBK379740. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Pages with reference errors

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- CS1: long volume value

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2015

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2020

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Wikipedia articles needing clarification from June 2018

- Articles with changed DrugBank identifier

- 21-Hydroxylase inhibitors

- Anxiolytics

- Benzodiazepines

- Chemical substances for emergency medicine

- Chloroarenes

- Euphoriants

- GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators

- Genentech brands

- Glycine receptor antagonists

- Hoffmann-La Roche brands

- Lactams

- TSPO ligands

- World Health Organization essential medicines (alternatives)

- RTT