Topiramate

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Topamax, Trokendi XR, Qudexy XR, others |

| Other names | Topiramic acid |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 300 mg[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a697012 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 80% |

| Protein binding | 13–17%; 15–41% |

| Metabolism | Liver (20–30%) |

| Elimination half-life | 19–25 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (70–80%) |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H21NO8S |

| Molar mass | 339.36 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Topiramate, sold under the brand name Topamax among others, is a medication used to treat epilepsy and prevent migraines.[2] It has also been used in alcohol dependence.[2] For epilepsy this includes treatment for generalized or focal seizures.[3] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include tingling, loss of appetite, feeling tired, abdominal pain, hair loss, and trouble concentrating.[2][3] Serious side effects may include suicide, increased ammonia levels resulting in encephalopathy, and kidney stones.[2] Use in pregnancy may result in harm to the baby and use during breastfeeding is not recommended.[4] How it works is unclear.[2]

Topiramate was approved for medical use in the United States in 1996.[2] It is available as a generic medication.[3] A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £1.40 per month as of 2019.[3] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$4.00.[5] In 2017, it was the 77th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than ten million prescriptions.[6][7]

Medical uses

Topiramate is used to treat epilepsy in children and adults, and it was originally used as an anticonvulsant.[8] In children, it is indicated for the treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, a disorder that causes seizures and developmental delay. It is most frequently prescribed for the prevention of migraines[8] as it decreases the frequency of attacks.[9][10] Topirimate is used to treat medication overuse headache and is recommended by the European Federation of Neurological Societies as one of the few medications showing effectiveness for this indication.[11]

Pain

A 2018 review found topiramate of no use in chronic low back pain.[12] Topiramate has not been shown to work as a pain medicine in diabetic neuropathy, the only neuropathic condition in which it has been adequately tested.[13]

Other

One common off-label use for topiramate is in the treatment of bipolar disorder.[14][15][16] A review published in 2010 suggested a benefit of topiramate in the treatment of symptoms of borderline personality disorder, however the authors noted that this was based only on one randomized controlled trial and requires replication.[17]

Topiramate has been used as a treatment for alcoholism.[18] The VA/DoD 2015 guideline on substance use disorders lists topiramate as a "strong for" in its recommendations for alcohol use disorder.[19]

Other uses include treatment of obesity[20][21] and antipsychotic-induced weight gain.[22][23] It is being studied to treat post traumatic stress disorder.[24] In 2012, the combination phentermine/topiramate was approved in the United States for weight loss.

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 300 mg by mouth.[1]

Side effects

People taking topiramate should be aware of the following risks:

- Avoid activities requiring mental alertness and coordination until drug effects are realized.

- Topiramate may impair heat regulation,[25] especially in children. Use caution with activities leading to an increased core temperature, such as strenuous exercise, exposure to extreme heat, or dehydration.

- Topiramate may cause visual field defects.[26]

- Topiramate may decrease effectiveness of oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives.

- Taking topiramate in the first trimester of pregnancy may increase risk of cleft lip/cleft palate in infant.[27]

- As is the case for all antiepileptic drugs, it is advisable not to suddenly discontinue topiramate as there is a theoretical risk of rebound seizures.

Frequency

Adverse effects by incidence:[28][29][30][31]

Very common (>10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Dizziness

- Weight loss

- Paraesthesia – e.g., pins and needles

- Somnolence

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Fatigue

- Nasopharyngitis

- Depression

Uncommon (1-10% incidence) adverse effects include:

- Weight gain

- Anaemia

- Disturbance in attention

- Memory impairment

- Amnesia

- Cognitive disorder

- Mental impairment

- Psychomotor skills impaired

- Convulsion

- Coordination abnormal

- Tremor

- Lethargy

- Hypoaesthesia (reduced sense of touch)

- Nystagmus

- Dysgeusia

- Balance disorder

- Dysarthria

- Intention tremor

- Sedation

- Blurred vision

- Diplopia (double vision)

- Visual disturbance

- Vertigo

- Tinnitus

- Ear pain

- Dyspnoea

- Epistaxis

- Nasal congestion

- Rhinorrhoea

- Vomiting

- Constipation

- Abdominal pain upper

- Dyspepsia

- Abdominal pain

- Dry mouth

- Stomach discomfort

- Paraesthesia oral

- Gastritis

- Abdominal discomfort

- Nephrolithiasis

- Pollakisuria

- Dysuria

- Alopecia (hair loss)

- Rash

- Pruritus

- Arthralgia

- Muscle spasms

- Myalgia

- Muscle twitching

- Muscular weakness

- Musculoskeletal chest pain

- Decreased appetite

- Pyrexia

- Asthenia

- Irritability

- Gait disturbance

- Feeling abnormal

- Malaise

- Hypersensitivity

- Bradyphrenia (slowness of thought)

- Insomnia

- Expressive language disorder

- Anxiety

- Confusional state

- Disorientation

- Aggression

- Mood altered

- Agitation

- Mood swings

- Anger

- Abnormal behaviour

Rarely, the inhibition of carbonic anhydrase may be strong enough to cause metabolic acidosis of clinical importance.[32]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has notified prescribers that topiramate can cause acute myopia and secondary angle closure glaucoma in a small subset of people who take topiramate regularly.[33] The symptoms, which typically begin in the first month of use, include blurred vision and eye pain. Discontinuation of topiramate may halt the progression of the ocular damage and may reverse the visual impairment.

Preliminary data suggests that, as with several other anti-epileptic drugs, topiramate carries an increased risk of congenital malformations.[34] This might be particularly important for women who take topiramate to prevent migraine attacks. In March 2011, the FDA notified healthcare professionals and patients of an increased risk of development of cleft lip and/or cleft palate (oral clefts) in infants born to women treated with Topamax (topiramate) during pregnancy and placed it in Pregnancy Category D.[27]

Topiramate has been associated with a statistically significant increase in suicidality,[35] and "suicidal thoughts or actions" is now listed as one of the possible side effects of the drug "in a very small number of people, about 1 in 500."[25][36]

Overdose

Symptoms of acute and acute on chronic exposure to topiramate range from asymptomatic to status epilepticus, including in patients with no seizure history.[37][38] In children, overdose may also result in hallucinations.[38] Topiramate has been deemed the primary substance that led to fatal overdoses in cases that were complicated by polydrug exposure.[39] The most common signs of overdose are dilated pupils, somnolence, dizziness, psychomotor agitation, and abnormal, uncoordinated body movements.[37][38][39]

Symptoms of overdose may include but are not limited to:[citation needed]

- Agitation

- Depression

- Speech problems

- Blurred vision, double vision

- Troubled thinking

- Loss of coordination

- Inability to respond to things around you

- Loss of consciousness

- Confusion and coma

- Fainting

- Upset stomach and stomach pain

- Loss of appetite and vomiting

- Shortness of breath; fast, shallow breathing

- Pounding or irregular heartbeat

- Muscle weakness

- Bone pain

- Seizures

A specific antidote is not available. Treatment is entirely supportive.

Interactions

Topiramate has many drug-drug interactions. Some of the most common are listed below:

- As topiramate inhibits carbonic anhydrase, use with other inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase (e.g. acetazolamide) increases the risk of kidney stones.[citation needed]

- Enzyme inducers (e.g. carbamazepine) can increase the elimination of topiramate, possibly necessitating dose escalations of topiramate.[citation needed]

- Topiramate may increase the plasma-levels of phenytoin.

- Topiramate itself is a weak inhibitor of CYP2C19 and induces CYP3A4; a decrease in plasma levels of estrogens and digoxin has been noted during topiramate therapy. This can reduce the effectiveness of oral contraceptives (birth control pills); use of alternative birth control methods is recommended.[40] Neither intrauterine devices (IUDs) nor Depo-Provera are affected by topiramate.[40]

- Alcohol may cause increased sedation or drowsiness, and increase the risk of having a seizure.

- As topiramate may result in acidosis other treatments that also do so may worsen this effect.[41]

- Oligohidrosis and hyperthermia were reported in post-marketing reports about topiramate; antimuscarinic drugs (like trospium) can aggravate these disorders.[citation needed]

Pharmacology

Chemically, topiramate is a sulfamate modified fructose diacetonide - a rather unusual chemical structure for a pharmaceutical.

Topiramate is quickly absorbed after oral use. Most of the drug (70%) is excreted in the urine unchanged. The remainder is extensively metabolized by hydroxylation, hydrolysis, and glucuronidation. Six metabolites have been identified in humans, none of which constitutes more than 5% of an administered dose.

Several cellular targets have been proposed to be relevant to the therapeutic activity of topiramate.[42] These include (1) voltage-gated sodium channels; (2) high-voltage-activated calcium channels; (3) GABA-A receptors; (4) AMPA/kainate receptors; and (5) carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes. There is evidence that topiramate may alter the activity of its targets by modifying their phosphorylation state instead of by a direct action.[43] The effect on sodium channels could be of particular relevance for seizure protection. Although topiramate does inhibit high-voltage-activated calcium channels, the relevance to clinical activity is uncertain. Effects on specific GABA-A receptor isoforms could also contribute to the antiseizure activity of the drug. Topiramate selectively inhibits cytosolic (type II) and membrane associated (type IV) forms of carbonic anhydrase. The action on carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes may contribute to the drug's side-effects, including its propensity to cause metabolic acidosis and calcium phosphate kidney stones.

Topiramate inhibits maximal electroshock and pentylenetetrazol-induced seizures as well as partial and secondarily generalized tonic-clonic seizures in the kindling model, findings predictive of a broad spectrum of activities clinically. Its action on mitochondrial permeability transition pores has been proposed as a mechanism.[44]

While many anticonvulsants have been associated with apoptosis in young animals, animal experiments have found that topiramate is one of the very few anticonvulsants [see: levetiracetam, carbamazepine, lamotrigine] that do not induce apoptosis in young animals at doses needed to produce an anticonvulsant effect.[45]

Detection in body fluids

Blood, serum, or plasma topiramate concentrations may be measured using immunoassay or chromatographic methods to monitor therapy, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients, or to assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Plasma levels are usually less than 10 mg/L during therapeutic administration, but can range from 10–150 mg/L in overdose victims.[46][47][48]

History

Topiramate was discovered in 1979 by Bruce E. Maryanoff and Joseph F. Gardocki during their research work at McNeil Pharmaceuticals.[49][50] The commercial usage of Topiramate began in 1996.[51] Mylan Pharmaceuticals was granted final approval by the FDA for the sale of generic topiramate in the United States and the generic version was made available in September 2006.[52] The last patent for topiramate in the U.S. was for use in children and expired on February 28, 2009.[53]

Society and culture

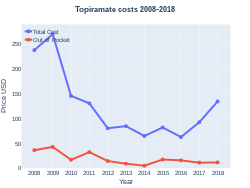

Cost

A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £1.40 per month as of 2019.[3] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$4.00.[5] In 2017, it was the 77th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than ten million prescriptions.[6][7]

-

Topiramate costs (US)

-

Topiramate prescriptions (US)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Topiramate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 328. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ "Topiramate Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Topiramate - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. 23 December 2019. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Topamax Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ↑ Linde, M; Mulleners, WM; Chronicle, EP; McCrory, DC (24 June 2013). "Topiramate for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD010610. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010610. PMID 23797676.

- ↑ Ferrari, A; Tiraferri, I; Neri, L; Sternieri, E (September 2011). "Clinical pharmacology of topiramate in migraine prevention". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 7 (9): 1169–81. doi:10.1517/17425255.2011.602067. PMID 21756204.

- ↑ Evers, S.; Jensen, R. (September 2011). "Treatment of medication overuse headache - guideline of the EFNS headache panel". European Journal of Neurology. 18 (9): 1115–1121. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03497.x.

- ↑ Enke, Oliver; New, Heather A.; New, Charles H.; Mathieson, Stephanie; McLachlan, Andrew J.; Latimer, Jane; Maher, Christopher G.; Lin, C.-W. Christine (2 July 2018). "Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 190 (26): E786–E793. doi:10.1503/cmaj.171333. PMC 6028270. PMID 29970367.

- ↑ Wiffen, PJ; Derry S; Lunn MPT; Moore R. (August 2013). "Topiramate for neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD008314. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008314.pub3. PMID 23996081. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ↑ Arnone, D (2005). "Review of the use of Topiramate for treatment of psychiatric disorders". Annals of General Psychiatry. 4 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/1744-859X-4-5. PMC 1088011. PMID 15845141.

- ↑ Vasudev, K; Macritchie, K; Geddes, J; Watson, S; Young, A (25 January 2006). "Topiramate for acute affective episodes in bipolar disorder". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD003384. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003384.pub2. PMID 16437453.

- ↑ Cipriani, A; Barbui, C; Salanti, G; Rendell, J; Brown, R; Stockton, S; Purgato, M; Spineli, LM; Goodwin, GM; Geddes, JR (8 October 2011). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 378 (9799): 1306–15. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60873-8. PMID 21851976.

- ↑ Leib, Klaus; Völlm, Birgit; Rücker, Gerta; Timmer, Antje; Stoffers, Jutta M (2010). "Pharmacotherapy for borderline personality disorder: Cochrane systematic review of randomised trials". British Journal of Psychiatry. 196 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.062984. PMID 20044651.

- ↑ Johnson, BA; Ait-Daoud, N (2010). "Topiramate in the new generation of drugs: efficacy in the treatment of alcoholic patients". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 16 (19): 2103–12. doi:10.2174/138161210791516404. PMC 3063512. PMID 20482511.

- ↑ "VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of substance use disorders" (PDF). healthquality.va.gov. 31 December 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ↑ Verrotti A, Scaparrotta A, Agostinelli S, Di Pillo S, Chiarelli F, Grosso S (August 2011). "Topiramate-induced weight loss: a review". Epilepsy Research. 95 (3): 189–99. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.05.014. PMID 21684121.

- ↑ Kramer, CK; Leitão, CB; Pinto, LC; Canani, LH; Azevedo, MJ; Gross, JL (May 2011). "Efficacy and safety of topiramate on weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Obesity Reviews. 12 (5): e338–47. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00846.x. PMID 21438989.

- ↑ Hahn, MK; Cohn, T; Teo, C; Remington, G (January 2013). "Topiramate in schizophrenia: a review of effects on psychopathology and metabolic parameters". Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 6 (4): 186–96. doi:10.3371/CSRP.HACO.01062013. PMID 23302448.

- ↑ Mahmood, S; Booker, I; Huang, J; Coleman, CI (February 2013). "Effect of topiramate on weight gain in patients receiving atypical antipsychotic agents". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 33 (1): 90–4. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e31827cb2b7. PMID 23277264.

- ↑ Andrus, MR; Gilbert, E (November 2010). "Treatment of civilian and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder with topiramate". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 44 (11): 1810–6. doi:10.1345/aph.1P163. PMID 20923947.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Possible Side Effects - TOPAMAX® (topiramate)". Topamax.xom. Archived from the original on 28 January 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ↑ "Topamax (topiramate) tablets and sprinkle capsules". Fda.gov. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Report a Serious Problem (6 January 2011). "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Risk of oral clefts in children born to mothers taking Topamax (topiramate)". Fda.gov. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ "TOPAMAX® Tablets and Sprinkle Capsules PRODUCT INFORMATION" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. JANSSEN-CILAG Pty Ltd. 30 May 2013. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "topiramate (Rx) - Topamax, Trokendi XR". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "Topiramate 100 mg film-coated Tablets". electronic Medicines Compendium. Sandoz Limited. 6 March 2013. Archived from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "TOPIRAMATE ( topiramate ) tablet TOPIRAMATE ( topiramate ) tablet [Torrent Pharmaceuticals Limited]". DailyMed. Torrent Pharmaceuticals Limited. August 2011. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ Mirza, Nasir; Marson, Anthony G.; Pirmohamed, Munir (2009). "Effect of topiramate on acid-base balance: extent, mechanism and effects". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 68 (5): 655–61. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03521.x. PMC 2791971. PMID 19916989.

- ↑ Hulihan, Joseph (2001). "IMPORTANT DRUG WARNING" (PDF). FDA MedWatch. Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ Hunt, S; Russell, A; Smithson, WH; Parsons, L; Robertson, I; Waddell, R; Irwin, B; Morrison, PJ; Morrow, J (2008). "Topiramate in pregnancy: preliminary experience from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register". Neurology. 71 (4): 272–6. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000318293.28278.33. PMID 18645165. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- ↑ "Suicidality and Antiepileptic Drugs" (PDF). Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ [1] Archived August 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Wiśniewski; et al. (2009), "Acute topiramate overdose – clinical manifestations", Clinical Toxicology, 47 (4): 317–320, doi:10.1080/15563650601117954, ISSN 1556-9519, PMID 19514879

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Wills; et al. (2014), "Clinical Outcomes in Newer Anticonvulsant Overdose: A Poison Center Observational Study", J. Med. Toxicol., 10 (3): 254–260, doi:10.1007/s13181-014-0384-5, PMC 4141920, PMID 24515527

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Lofton, AL; Klein-Schwartz, W (2005), "Evaluation of toxicity of topiramate exposures reported to poison centers", Human & Experimental Toxicology, 24 (11): 591–595, doi:10.1191/0960327105ht561oa, PMID 16323576

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The complete drug reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 2068. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ↑ FDA.gov Archived February 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Porter RJ, Dhir A, Macdonald RL, Rogawski MA (2012). "Mechanisms of action of antiseizure drugs". Handb Clin Neurol. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 108. pp. 663–681. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52899-5.00021-6. ISBN 9780444528995. PMID 22939059. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ Meldrum BS, Rogawski MA (2007). "Molecular targets for antiepileptic drug development". Neurotherapeutics. 4 (1): 18–61. doi:10.1016/j.nurt.2006.11.010. PMC 1852436. PMID 17199015.

- ↑ Kudin, AP; Debska-Vielhaber, G; Vielhaber, S; Elger, CE; Kunz, WS (2004). "The mechanism of neuroprotection by topiramate in an animal model of epilepsy". Epilepsia. 45 (12): 1478–87. doi:10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.13504.x. PMID 15571505.

- ↑ Czuczwar, K; Czuczwar, M; Cieszczyk, J; Gawlik, P; Luszczki, JJ; Borowicz, KK; Czuczwar, SJ (2004). "Neuroprotective activity of antiepileptic drugs". Przeglad Lekarski. 61 (11): 1268–71. PMID 15727029.

- ↑ Goswami D, Kumar A, Khuroo AH, et al. Bioanalytical LC-MS/MS method validation for plasma determination of topiramate in healthy Indian volunteers. Biomed. Chromatogr. 23: 1227-1241, 2009.

- ↑ Brandt C; Elsner H; Füratsch N; et al. (2010). "Topiramate overdose: a case report of a patient with extremely high topiramate serum concentrations and nonconvulsive status epilepticus". Epilepsia. 51 (6): 1090–1093. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02395.x. PMID 19889015.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1567-1569.

- ↑ Maryanoff, BE; Nortey, SO; Gardocki, JF; Shank, RP; Dodgson, SP (1987). "Anticonvulsant O-alkyl sulfamates. 2,3:4,5-Bis-O-(1-methylethylidene)-beta-D-fructopyranose sulfamate and related compounds". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 30 (5): 880–7. doi:10.1021/jm00388a023. PMID 3572976.

- ↑ Maryanoff, BE; Costanzo, MJ; Nortey, SO; Greco, MN; Shank, RP; Schupsky, JJ; Ortegon, MP; Vaught, JL (1998). "Structure-activity studies on anticonvulsant sugar sulfamates related to topiramate. Enhanced potency with cyclic sulfate derivatives". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 41 (8): 1315–43. doi:10.1021/jm970790w. PMID 9548821.

- ↑ Pitkänen, Asla; Schwartzkroin, Philip A.; Moshé, Solomon L. (2005). Models of Seizures and Epilepsy. Burlington: Elsevier. p. 539. ISBN 9780080457024. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.

- ↑ "First-Time Generic Approvals: Seasonale, Imodium Advanced, and Topamax". Medscape.com. 22 September 2006. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2013.

- ↑ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations". Accessdata.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- FAQ: Topiramate (Topamax), Mood Disorders and PTSD Archived 13 October 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Use dmy dates from April 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2013

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2016

- Articles with changed DrugBank identifier

- American inventions

- AMPA receptor antagonists

- Anticonvulsants

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors

- GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators

- Johnson & Johnson brands

- Kainate receptor antagonists

- Monosaccharide derivatives

- Sodium channel blockers

- Sulfamates

- RTT