Nefazodone

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Serzone, Dutonin, Nefadar, others |

| Other names | BMY-13754-1; MJ-13754-1 |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Antidepressant[1] |

| Main uses | Major depressive disorder[1] |

| Side effects | Sleepiness, dry mouth, nausea, constipation, blurry vision, confusion[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Typical dose | 300 to 600 mg/day[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a695005 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 20% (variable)[2] |

| Protein binding | 99% (loosely)[2] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4, CYP2D6)[3] |

| Metabolites | • Hydroxynefazodone[2] • mCPP[2] • p-Hydroxynefazodone[3] • Triazoledione[2] |

| Elimination half-life | • Nefazodone: 2–4 hours[2] • Hydroxynefazodone: 1.5–4 hours[2] • Triazoledione: 18 hours[2] • mCPP: 4–8 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Urine: 55% Feces: 20–30% |

| Chemical and physical data | |

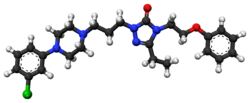

| Formula | C25H32ClN5O2 |

| Molar mass | 470.01 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Nefazodone, sold under various brand names, is a medication primarily used to treat major depressive disorder.[1] Other uses include aggressive behavior and panic disorder.[4] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include sleepiness, dry mouth, nausea, constipation, blurry vision, and confusion.[1] Other side effects may include liver problems, suicide, bipolar disorder, seizures, and priapism.[1] Safety in pregnancy is unclear.[5] How it works in not entirely clear but may involved effects on 5-HT and norepinephrine within the brain.[2]

Nefazodone was patented in 1982 and approved for medical use in the United States in 1988.[4][6] It is available as a generic medication.[1] In the United States it costs about 260 USD per month as of 2021.[7] It is no longer commonly used due to concerns with liver problems.[4] It was removed from the market in Europe, Canada, and Australia as of 2004.[8]

Medical uses

Nefazodone is used to treat major depressive disorder, aggressive behavior, and panic disorder.[9]

Dosage

It is started at a dose of 100 mg twice per day with the typical dose being 300 to 600 mg total per day.[1]

Nefazodone is available as 50 mg, 100 mg, 150 mg, 200 mg, and 250 mg tablets for oral ingestion.[10]

Side effects

Common and mild side effects include dry mouth (25%), sleepiness (25%), nausea (22%), dizziness (17%), blurred vision (16%), weakness (11%), lightheadedness (10%), confusion (7%), and orthostatic hypotension (5%). Rare and serious adverse reactions may include allergic reactions, fainting, painful/prolonged erection, and jaundice.[11]

Nefazodone can cause severe liver damage, leading to a need for liver transplant, and death. The incidence of severe liver damage is approximately 1 in every 250,000 to 300,000 patient-years.[12][11]By the time that it started to be withdrawn in 2003, nefazodone had been associated with at least 53 cases of liver injury, with 11 deaths, in the United States,[13] and 51 cases of liver toxicity, with 2 cases of liver transplantation, in Canada.[14][15] In a Canadian study which found 32 cases in 2002, it was noted that databases like that used in the study tended to include only a small proportion of suspected drug reactions.[15]

Nefazodone is not especially associated with increased appetite and weight gain.[16]

Interactions

Nefazodone is a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4, and may interact adversely with many commonly used medications that are metabolized by CYP3A4.[17][18][19]

Pharmacology

Nefazodone is a phenylpiperazine compound and is related to trazodone. It has been described as a serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARI) due to its combined actions as a potent serotonin 5-HT2A receptor and 5-HT2C receptor antagonist and weak serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI).

Pharmacodynamics

| Site | Ki (nM) | Species | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERT | 200–459 | Human | [21][22] |

| NET | 360–618 | Human | [21][22] |

| DAT | 360 | Human | [21] |

| 5-HT1A | 80 | Human | [23] |

| 5-HT2A | 26 | Human | [23] |

| 5-HT2C | 72 | Human | [24] |

| α1 | 5.5–48 | Human | [23][22] |

| α1A | 48 | Human | [24] |

| α2 | 84–640 | Human | [23][22] |

| β | >10,000 | Rat | [25] |

| D2 | 910 | Human | [23] |

| H1 | ≥370 | Human | [23][24] |

| mACh | >10,000 | Human | [23] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. | |||

Nefazodone acts primarily as a potent antagonist of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor and to a lesser extent of the serotonin 5-HT2C receptor.[23] It also has high affinity for the α1-adrenergic receptor and serotonin 5-HT1A receptor, and relatively lower affinity for the α2-adrenergic receptor and dopamine D2 receptor.[23] Nefazodone has low but significant affinity for the serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine transporters as well, and therefore acts as a weak serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI).[21] It has low but potentially significant affinity for the histamine H1 receptor, where it is an antagonist, and hence may have some antihistamine activity.[23][24] Nefazodone has negligible activity at muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, and accordingly, has no anticholinergic effects.[21]

Pharmacokinetics

The bioavailability of nefazodone is low and variable, about 20%.[2] Its plasma protein binding is approximately 99%, but it is bound loosely.[2]

Nefazodone is metabolized in the liver, with the main enzyme involved thought to be CYP3A4.[3] The drug has at least four active metabolites, which include hydroxynefazodone, para-hydroxynefazodone, triazoledione, and meta-chlorophenylpiperazine.[2] Nefazodone has a short elimination half-life of about 2 to 4 hours.[2] Its metabolite hydroxynefazodone similarly has an elimination half-life of about 1.5 to 4 hours, whereas the elimination half-lives of triazoledione and mCPP are longer at around 18 hours and 4 to 8 hours, respectively.[2] Due to its long elimination half-life, triazole is the major metabolite and predominates in the circulation during nefazodone treatment, with plasma levels that are 4 to 10 times higher than those of nefazodone itself.[2][26] Conversely, hydroxynefazodone levels are about 40% of those of nefazodone at steady state.[2] Plasma levels of mCPP are very low at about 7% of those of nefazodone; hence, mCPP is only a minor metabolite.[2][26] mCPP is thought to be formed from nefazodone specifically by CYP2D6.[3][26]

The ratios of brain-to-plasma concentrations of mCPP to nefazodone are 47:1 in mice and 10:1 in rats, suggesting that brain exposure to mCPP may be much higher than plasma exposure.[2] Conversely, hydroxynefazodone levels in the brain are 10% of those in plasma in rats.[2] As such, in spite of its relatively low plasma concentrations, brain exposure to mCPP may be substantial, whereas that of hydroxynefazodone may be minimal.[2]

Chemistry

Nefazodone is a phenylpiperazine;[27] it is an alpha-phenoxyl derivative of etoperidone which in turn was a derivative of trazodone.[28]

History

Nefazodone was discovered by scientists at Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) who were seeking to improve on trazodone by reducing its sedating qualities.[28]

BMS obtained marketing approvals worldwide for nefazodone in 1994.[12] It was marketed in the US under the brand name Serzone[29] and in Europe under the brand name Dutonin.[30]

In 2002 the FDA obligated BMS to add a black box warning about potential fatal liver toxicity to the drug label.[31][8] Worldwide sales in 2002 were $409 million.[30]

In 2003 Public Citizen filed a citizen petition asking the FDA to withdraw the marketing authorization in the US, and in early 2004 the organization sued the FDA to attempt to force withdrawal of the drug.[31][32] The FDA issued a response to the petition in June 2004 and filed a motion to dismiss, and Public Citizen withdrew the suit.[32]

Generic versions were introduced in the US in 2003[33] and Health Canada withdrew the marketing authorization that year.[34]

Sales of nefazodone were about $100 million in 2003.[35] By that time it was also being marketed under the additional brand names Serzonil, Nefadar, and Rulivan.[12]

In April 2004, BMS announced that it was going discontinue the sale of Serzone in the US in June 2004 and said that this was due to declining sales.[8][35] By that time BMS had already withdrawn the drug from the market in Europe, Australia, New Zealand and Canada.[8]

As of 2012 generic nefazodone was available in the US.[36]

Society and culture

Generic names

Nefazodone is the generic name of the drug and its INN and BAN, while néfazodone is its DCF and nefazodone hydrochloride is its USAN and USP.[6][37][38][39]

Brand names

Nefazodone has been marketed under a number of brand names including Dutonin (AT, ES, IE, UK), Menfazona (ES), Nefadar (CH, DE, NO, SE), Nefazodone BMS (AT), Nefazodone Hydrochloride Teva (US), Reseril (IT), Rulivan (ES), and Serzone (AU, CA, US).[37][39] As of 2017, it remains available only on a limited basis as Nefazodone Hydrochloride Teva in the United States.[39]

Research

The use of nefazodone to prevent migraine has been studied, due to its antagonistic effects on the 5-HT2A[40] and 5-HT2C receptors.[41][42]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 "Nefazodone Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 Alan F. Schatzberg, M.D.; Charles B. Nemeroff, M.D., Ph.D. (2017). The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Pub. pp. 460–. ISBN 978-1-58562-523-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Gian Maria Pacifici; Olavi Pelkonen (24 May 2001). Interindividual Variability in Human Drug Metabolism. CRC Press. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-0-7484-0864-1. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Nefazodone". LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2012. Archived from the original on 2021-05-06. Retrieved 2021-11-12.

- ↑ "Nefazodone (Serzone) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 857–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "Nefazodone Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Cosgrove-Mather, Bootie (April 15, 2004). "Anti-Depressant Taken Off Market". CBS News. Archived from the original on December 2, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ↑ Nefazodone. LiverTox (NIDDK). 2 June 2017. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "Nefazodone - FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses". Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Serzone (Nefazodone): Side Effects, Interactions, Warning, Dosage & Uses". RxList. January 2005. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Drugs of Current Interest: Nefazodone". WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter (1). 2003. Archived from the original on 2018-04-30. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ↑ Edwards IR (April 2003). "Withdrawing drugs: nefazodone, the start of the latest saga". Lancet. 361 (9365): 1240. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13030-9. PMID 12699949. S2CID 39993080.

- ↑ Choi S (November 2003). "Nefazodone (Serzone) withdrawn because of hepatotoxicity". CMAJ. 169 (11): 1187. PMC 264962. PMID 14638657.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Stewart DE (May 2002). "Hepatic adverse reactions associated with nefazodone". Can J Psychiatry. 47 (4): 375–7. doi:10.1177/070674370204700409. PMID 12025437.

- ↑ Sussman N, Ginsberg DL, Bikoff J (April 2001). "Effects of nefazodone on body weight: a pooled analysis of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor- and imipramine-controlled trials". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62 (4): 256–60. doi:10.4088/JCP.v62n0407. PMID 11379839.

- ↑ Lexi-Comp (September 2008). "Nefazodone". The Merck Manual Professional. Archived from the original on 2010-09-04. Retrieved 2021-10-20. Retrieved on November 29, 2008.

- ↑ Spina E, Santoro V, D'Arrigo C (July 2008). "Clinically relevant pharmacokinetic drug interactions with second-generation antidepressants: an update". Clin Ther. 30 (7): 1206–27. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(08)80047-1. PMID 18691982.

- ↑ Richelson, Elliott (1997). "Pharmacokinetic Drug Interactions of New Antidepressants: A Review of the Effects on the Metabolism of Other Drugs". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 72 (9): 835–847. doi:10.4065/72.9.835. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 9294531. Archived from the original on 2021-10-28. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ↑ Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E (1997). "Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 340 (2–3): 249–58. doi:10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. PMID 9537821.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Owens MJ, Morgan WN, Plott SJ, Nemeroff CB (1997). "Neurotransmitter receptor and transporter binding profile of antidepressants and their metabolites". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 283 (3): 1305–22. PMID 9400006.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 23.8 23.9 Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E (1994). "Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds". Psychopharmacology. 114 (4): 559–65. doi:10.1007/bf02244985. PMID 7855217. S2CID 21236268.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Roth BL, Kroeze WK (2006). "Screening the receptorome yields validated molecular targets for drug discovery". Curr. Pharm. Des. 12 (14): 1785–95. doi:10.2174/138161206776873680. PMID 16712488.

- ↑ Sánchez C, Hyttel J (1999). "Comparison of the effects of antidepressants and their metabolites on reuptake of biogenic amines and on receptor binding". Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 19 (4): 467–89. doi:10.1023/A:1006986824213. PMID 10379421. S2CID 19490821.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Sheldon H. Preskorn; Christina Y. Stanga; John P. Feighner; Ruth Ross (6 December 2012). Antidepressants: Past, Present and Future. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 68–. ISBN 978-3-642-18500-7.

- ↑ Davis, Rick; Whittington, Ruth; Bryson, Harriet M. (April 1997). "Nefazodone". Drugs. 53 (4): 608–636. doi:10.2165/00003495-199753040-00006. PMID 9098663.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Eison, Michael S.; Taylor, Duncan B.; Riblet, Leslie A. (1987). "Atypical Psychotropic Agents". In Williams, Michael; Malick, Jeffrey B. (eds.). Drug Discovery and Development. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 390. ISBN 9781461248286. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ↑ Associated Press (16 March 2004). "Consumer group seeks ban on antidepressant". NBC News. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Hoffmann, Candace (January 8, 2003). "Bristol-Myers to withdraw Dutonin in Europe". First Word Pharma. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Public Citizen to sue FDA over Serzone - Pharmaceutical industry news". The Pharma Letter. 22 March 2004. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "Court Decisions and Updates" (PDF). FDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ↑ "Nefazodone". Drug Patent Watch. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ↑ Lexchin, J (15 March 2005). "Drug withdrawals from the Canadian market for safety reasons, 1963-2004". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal. 172 (6): 765–7. doi:10.1503/cmaj.045021. PMC 552890. PMID 15767610.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 DeNoon, Daniel J. (May 4, 2004). "Company Pulls Antidepressant Off Market". WebMD. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ↑ Sadock, Benjamin J.; Sadock, Virginia A.; Sussman, Norman (2012). "22. Nefazodone". Kaplan & Sadock's Pocket Handbook of Psychiatric Drug Treatment. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 251. ISBN 9781451154467. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 722–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ↑ I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 190–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 "Nefazodone International Brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ↑ Saper JR, Lake AE, Tepper SJ (May 2001). "Nefazodone for chronic daily headache prophylaxis: an open-label study". Headache. 41 (5): 465–74. doi:10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.01084.x. PMID 11380644. S2CID 32785110.

- ↑ Mylecharane EJ (1991). "5-HT2 receptor antagonists and migraine therapy". J. Neurol. 238 (Suppl 1): S45–52. doi:10.1007/BF01642906. PMID 2045831. S2CID 5941834.

- ↑ Millan MJ (2005). "Serotonin 5-HT2C receptors as a target for the treatment of depressive and anxious states: focus on novel therapeutic strategies". Thérapie. 60 (5): 441–60. doi:10.2515/therapie:2005065. PMID 16433010.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Alpha-1 blockers

- Alpha-2 blockers

- Antidepressants

- Anxiolytics

- 5-HT1A agonists

- 5-HT2A antagonists

- 5-HT2C antagonists

- H1 receptor antagonists

- Hepatotoxins

- Phenol ethers

- 2-(3-(4-(3-chlorophenyl)piperazin-1-yl)propyl)-1,2,4-triazol-3-ones

- Serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors

- Ureas

- Withdrawn drugs

- RTT