Droperidol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /droʊˈpɛrIdɔːl/ |

| Trade names | Inapsine, Droleptan, Dridol, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | Nausea, agitation, migraines[1][2] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | Intravenous, intramuscular[1] |

| Onset of action | < 10 min[1] |

| Duration of action | Up to 12 hrs[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 2.3 hours |

| Chemical and physical data | |

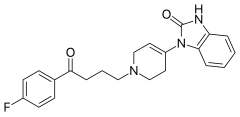

| Formula | C22H22FN3O2 |

| Molar mass | 379.435 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Droperidol is a medication used to prevent and treat nausea and vomiting including that due to chemotherapy.[1] It has also been used for sedative in those who are agitated and during anesthesia and for migraines.[1][2] It is given by injection into a vein or muscle.[1] Onset is within 10 minutes with a maximum effect up to 30 minutes.[1] Effects may last up to 12 hours.[1]

Common side effects include low blood pressure, movement disorders, fast heart rate, and sleepiness.[1] Other concerns include QT prolongation, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[1] Safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding is unclear.[3] It is in the butyrophenone family of medication and works by blocking dopamine receptors.[4]

Droperidol came into medical use in 1967.[5] It is available as a generic medication.[4] In 2001 the company making it stopped doing so.[5] It historically has been inexpensive.[5] Availability improved in 2019 as a new manufacturer entered the market.[6] In the United Kingdom 2.5 mg of injectable solution costs the NHS about 4 pounds as of 2020.[4]

Medical use

Nausea

Droperidol is used to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting in adults. For treatment of nausea and vomiting, droperidol and ondansetron are equally effective; droperidol is more effective than metoclopramide.[7]

Some practitioners recommend the use of 0.5 mg to 1 mg intravenously for the treatment of vertigo in an otherwise healthy elderly who have not responded to Epley maneuvers.

Agitation

Evidence supports the use of droperidol for psychosis of recent onset.[8] For agitation benefits begin within 5 to 10 minutes when used intravenously.[9] It has the benefit over haloperidol and lorazapam of being faster in onset.[10]

It also appears safe and effective in children with severe agitation.[11]

Migraines

Droperidol is probably useful in migraine headaches.[12]

Dosage

The typical dose is 0.625 to 1.25 mg every 6 hours as needed for nausea.[4] In the elderly the lower range of doses is recommended.[4] For agitation 5 mg may be used.[1] For migraines it may be used at a dose of 2.5 mg.[2]

Side effects

Dysphoria, sedation, hypotension resulting from peripheral alpha adrenoceptor blockade, prolongation of QT interval which can lead to torsades de pointes, and extrapyramidal side effects such as dystonic reactions/neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[13]

Black box

In 2001, the FDA added a Black Box Warning, citing concerns of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. The evidence for this is disputed, with 9 reported cases of torsades in 30 years and all of those having received doses in excess of 5 mg.[14] QT prolongation is a dose-related effect,[15] and it appears that droperidol is not a significant risk in low doses.

Many consider the risks to be over stated at typical doses.[12] A review of the cases submitted to the FDA found that most cases were not related to droperidol and ondansetron has similar QT prolonging effects.[16] Doses that have resulted in concerns have been greater than 300 mg.[6] As of 2019 there does not appear to be a need to routinely get an ECG before giving the medication or for continuous QT monitoring afterwards.[17][18]

A study in 2015 showed that droperidol is relatively safe and effective for the management of violent and aggressive adults[19] in hospital emergency departments in doses of 10mg and above and that there was no increased risk of QT prolongation and torsades de pointes.

Chemistry

Droperidol is synthesized from 1-benzyl-3-carbethoxypiperidin-4-one,

which is reacted with o-phenylenediamine. Evidently, the first derivative that is formed under the reaction conditions, 1,5-benzodiazepine, rearranges into 1-(1-benzyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydro-4-piridyl)-2-benzymidazolone. Debenzylation of the resulting product with hydrogen over a palladium catalyst, and subsequent alkylation of this using 4-chloro-4'-fluorobutyrophenone yields droperidol.

- C. Janssen, NV Res. Lab., GB 989755 (1962).

- Janssen, P. A. J.; 1963, Belgian Patent BE 626307.

- F.J. Gardocki, J. Janssen, U.S. Patent 3,141,823 (1964).

- P.A.J. Janssen, U.S. Patent 3,161,645 (1964).

History

Discovered at Janssen Pharmaceutica in 1961, droperidol is a butyrophenone which acts as a potent D2 (dopamine receptor) antagonist with some histamine and serotonin antagonist activity.[20]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 "Droperidol Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Thomas, MC; Musselman, ME; Shewmaker, J (February 2015). "Droperidol for the treatment of acute migraine headaches". The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 49 (2): 233–40. doi:10.1177/1060028014554445. PMID 25416184.

- ↑ "Droperidol (Inapsine) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 BNF 79 : March 2020. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2020. p. 452. ISBN 9780857113658.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Richards, JR; Schneir, AB (May 2003). "Droperidol in the emergency department: is it safe?". The Journal of emergency medicine. 24 (4): 441–7. doi:10.1016/s0736-4679(03)00044-1. PMID 12745049.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Droperidol Is Back (and Here's What You Need to Know)". ACEP Now. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ↑ Domino KB, Anderson EA, Polissar NL, Posner KL (June 1999). "Comparative efficacy and safety of ondansetron, droperidol, and metoclopramide for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 88 (6): 1370–9. doi:10.1213/00000539-199906000-00032. PMID 10357347.

- ↑ Khokhar, MA; Rathbone, J (15 December 2016). "Droperidol for psychosis-induced aggression or agitation". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 12: CD002830. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002830.pub3. PMID 27976370.

- ↑ Zun, LS (March 2018). "Evidence-Based Review of Pharmacotherapy for Acute Agitation. Part 1: Onset of Efficacy". The Journal of emergency medicine. 54 (3): 364–374. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.10.011. PMID 29361326.

- ↑ "Droperidol Is Back (and Here's What You Need to Know) - Page 3 of 3". ACEP Now. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ↑ Ramsden, SC; Pergjika, A; Janssen, AC; Mudahar, S; Fawcett, A; Walkup, JT; Hoffmann, JA (1 May 2022). "A systematic review of the effectiveness and safety of droperidol for pediatric agitation in acute care settings". Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. doi:10.1111/acem.14515. PMID 35490341.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lai, PC; Huang, YT (January 2018). "Evidence-based review and appraisal of the use of droperidol in the emergency department". Ci ji yi xue za zhi = Tzu-chi medical journal. 30 (1): 1–4. doi:10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_195_17. PMID 29643708.

- ↑ Park CK, Choi HY, Oh IY, Kim MS (2002). "Acute dystonia by droperidol during intravenous patient-controlled analgesia in young patients". J. Korean Med. Sci. 17 (5): 715–7. doi:10.3346/jkms.2002.17.5.715. PMC 3054934. PMID 12378031.

- ↑ Kao LW, Kirk MA, Evers SJ, Rosenfeld SH (April 2003). "Droperidol, QT prolongation, and sudden death: what is the evidence?". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 41 (4): 546–58. doi:10.1067/mem.2003.110. PMID 12658255.

- ↑ Lischke V, Behne M, Doelken P, Schledt U, Probst S, Vettermann J (November 1994). "Droperidol causes a dose-dependent prolongation of the QT interval". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 79 (5): 983–6. doi:10.1213/00000539-199411000-00028. PMID 7978420.

- ↑ Wilson, William C.; Grande, Christopher M.; Hoyt, David B. (2007). Trauma: Critical Care. CRC Press. p. 373. ISBN 978-1-4200-1684-0. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2020-10-13.

- ↑ "Droperidol Is Back (and Here's What You Need to Know) - Page 2 of 3". ACEP Now. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ↑ Perkins, Jack; Ho, Jeffrey D.; Vilke, Gary M.; DeMers, Gerard (July 2015). "American Academy of Emergency Medicine Position Statement: Safety of Droperidol Use in the Emergency Department". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 49 (1): 91–97. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.024.

- ↑ Calver, Leonie; Page, Colin; Downes, Michael; Chan, Betty; Kinnear, Frances; Wheatley, Luke; Spain, David; Ibister, Geoffrey (September 2015). "The safety and effectiveness of droperidol for sedation of acute behavioral disturbance in the emergency department". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 66 (3): 231–238. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.03.016. PMID 25890395. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ↑ Peroutka SJ, Synder SH (December 1980). "Relationship of neuroleptic drug effects at brain dopamine, serotonin, alpha-adrenergic, and histamine receptors to clinical potency". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 137 (12): 1518–22. doi:10.1176/ajp.137.12.1518. PMID 6108081. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

Further reading

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- Scuderi PE (2003). "Droperidol: Many questions, few answers". Anesthesiology. 98 (2): 289–90. doi:10.1097/00000542-200302000-00002. PMID 12552182.

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Multiple chemicals in Infobox drug

- Multiple chemicals in an infobox that need indexing

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Articles containing unverified chemical infoboxes

- Antiemetics

- Belgian inventions

- Benzimidazoles

- Butyrophenone antipsychotics

- Janssen Pharmaceutica

- Lactams

- Fluoroarenes

- Tetrahydropyridines

- Ureas

- Typical antipsychotics

- RTT