Gefitinib

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ɡɛˈfɪtɪnɪb/ |

| Trade names | Iressa, others |

| Other names | ZD1839 |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR inhibitor)[1] |

| Main uses | NSCLC[1] |

| Side effects | Rash, diarrhea, nausea, fever, mouth inflammation, eye problems, liver problems, kidney problems[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Typical dose | 250 mg OD[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607002 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 59% (by mouth) |

| Protein binding | 90% |

| Metabolism | Liver (mainly CYP3A4) |

| Elimination half-life | 6–49 hours |

| Excretion | Feces |

| Chemical and physical data | |

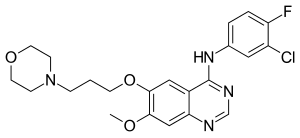

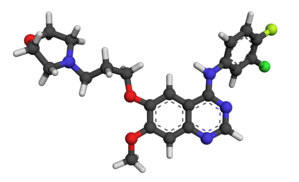

| Formula | C22H24ClFN4O3 |

| Molar mass | 446.91 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Gefitinib, sold under the brand name Iressa, is a medication used to treat non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).[1] Specifically it is used in cases which have certain mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor.[2] It is taken by mouth.[1]

Common side effects include rash, diarrhea, nausea, fever, mouth inflammation, eye problems, liver problems, and kidney problems.[1] Other side effects may include interstitial lung disease and infertility.[1] Use in pregnancy may harm the baby.[1] It is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor and EGFR inhibitor.[1]

Gefitinib was approved for medical use in the United States in 2003 and Europe in 2009.[1][3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines as an alternative to erlotinib.[4] It is available as a generic medication.[2] In the United Kingdom a month costs the NHS about £2,200 as of 2021.[2] This amount in the United States costs about 8,100 USD.[5]

Medical uses

Resistance

Gefitinib and other first-generation EGFR inhibitors reversibly bind to the receptor protein, effectively competing for the ATP binding pocket. Secondary mutations can arise that alter the binding site, the most common mutation being T790M, where a threonine is replaced by a methionine at amino acid position 790, which is in the ligand-binding domain that typically binds ATP.[6] Threonine 790 is the gatekeeper residue, meaning it is key in determining specificity in the binding pocket. When it is mutated into a methionine, researchers originally hypothesized that it caused drug inhibition due to the steric hindrance of the bulkier methionine that selected for the binding of ATP instead of gefitinib.[7] As of 2008, the current hypothesized mechanism is that resistance to gefitinib is conveyed by increasing the ATP affinity of EGFR on an enzymatic level, meaning that the protein preferentially binds ATP over gefitinib.[8]

In order to combat this acquired resistance to gefitinib and other first-generation inhibitors, researchers have used irreversible EGFR inhibitors like neratinib or dacomitinib, called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). These new drugs covalently bind to the ATP binding pocket, so when they are attached to EGFR, they cannot be displaced by ATP.[9] Even if the mutated versions of EGFR have a higher affinity for ATP, they will eventually use the irreversible inhibitors as ligands, which effectively shuts down their activity. When enough irreversible ligands have bound to EGFR, proliferation will be halted and apoptosis will be triggered through multiple pathways; for example, Bim can be activated after it is no longer inhibited by ERK, one of the kinases in the EGFR signaling pathway.[10] Even with gefitinib halting progression of NSCLC, the development of the cancer progresses after 9 to 13 months due to acquired resistances like the T790M mutation. These TKIs like dacomitinib extended overall survival by close to a year.[11]

Dosage

It is used at a dose of 250 mg once per day.[2]

Side effects

As gefitinib is a selective chemotherapeutic agent, its tolerability profile is better than previous cytotoxic agents. Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are acceptable for a potentially fatal disease.

Acne-like rash is reported very commonly. Other common adverse effects (≥1% of patients) include: diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, stomatitis, dehydration, skin reactions, paronychia, asymptomatic elevations of liver enzymes, asthenia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis.[12]

Infrequent side effects (0.1–1%) include: interstitial lung disease, corneal erosion, aberrant eyelash and hair growth.[12]

Mechanism of action

Gefitinib is the first selective inhibitor of epidermal growth factor receptor's (EGFR) tyrosine kinase domain. Thus gefitinib is an EGFR inhibitor. The target protein (EGFR) is a member of a family of receptors (ErbB) which includes Her1(EGFR), Her2(erb-B2), Her3(erb-B3) and Her4 (Erb-B4). EGFR is overexpressed in the cells of certain types of human carcinomas - for example in lung and breast cancers. This leads to inappropriate activation of the anti-apoptotic Ras signalling cascade, eventually leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation. Research on gefitinib-sensitive non-small cell lung cancers has shown that a mutation in the EGFR tyrosine kinase domain is responsible for activating anti-apoptotic pathways.[13][14] These mutations tend to confer increased sensitivity to tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as gefitinib and erlotinib. Of the types of non-small cell lung cancer histologies, adenocarcinoma is the type that most often harbors these mutations. These mutations are more commonly seen in Asians, women, and non-smokers (who also tend to more often have adenocarcinoma).

Gefitinib inhibits EGFR tyrosine kinase by binding to the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding site of the enzyme.[15] Thus the function of the EGFR tyrosine kinase in activating the anti-apoptotic Ras signal transduction cascade is inhibited, and malignant cells are inhibited.[16]

Society and culture

Gefitinib is currently[when?] marketed in over 64 countries.

Iressa was approved and marketed from July 2002 in Japan, making it the first country to import the drug.

The FDA approved gefitinib in May 2003 for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).[17] It was approved as monotherapy for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC after failure of both platinum-based and docetaxel chemotherapies.[17] i.e. as a third-line therapy.

In June 2005 the FDA withdrew approval for use in new patients due to lack of evidence that it extended life.[18]

In Europe gefitinib is indicated since 2009 in advanced NSCLC in all lines of treatment for patients harbouring EGFR mutations. This label was granted after gefitinib demonstrated as a first-line treatment to significantly improve progression-free survival vs. a platinum doublet regime in patients harbouring such mutations. IPASS has been the first of four phase III trials to have confirmed gefitinib superiority in this patient population.[19][20]

In most of the other countries where gefitinib is currently marketed it is approved for patients with advanced NSCLC who had received at least one previous chemotherapy regime. However, applications to expand its label as a first-line treatment in patients harbouring EGFR mutations is currently in process based on the latest scientific evidence.[citation needed] As at August 2012 New Zealand has approved gefitinib as first-line treatment for patients with EGFR mutation for naive locally advanced or metastatic, unresectable NSCLC. This is publicly funded for an initial 4-month term and renewal if no progression.[21]

On July 13, 2015, the FDA approved gefitinib as a first-line treatment for NSCLC.[22]

Research

IPASS (IRESSA Pan-Asia Study) was a randomized, large-scale, double-blinded study which compared gefitinib vs. carboplatin/ paclitaxel as a first-line treatment in advanced NSCLC.[23] IPASS studied 1,217 patients with confirmed adenocarcinoma histology who were former or never smokers. A pre-planned sub-group analyses showed that progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly longer for gefitinib than chemotherapy in patients with EGFR mutation positive tumours (HR 0.48, 95 per cent CI 0.36 to 0.64, p less than 0.0001), and significantly longer for chemotherapy than gefitinib in patients with EGFR mutation negative tumours (HR 2.85, 95 per cent CI 2.05 to 3.98, p less than 0.0001). This, in 2009, was the first time a targeted monotherapy has demonstrated significantly longer PFS than doublet chemotherapy.

EGFR diagnostic tests

Roche Diagnostics, Genzyme, QIAGEN, Argenomics S.A. & other companies make tests to detect EGFR mutations, designed to help predict which lung cancer patients may respond best to some therapies, including gefitinib and erlotinib.

The tests examine the genetics of tumors removed for biopsy for mutations that make them susceptible to treatment.

The EGFR mutation test may also help AstraZeneca win regulatory approval for use of their drugs as initial therapies. Currently the TK inhibitors are approved for use only after other drugs fail.[citation needed] In the case of gefitinib, the drug works only in about 10% of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, the most common type of lung cancer.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 "Gefitinib Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 BNF 81: March-September 2021. BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. 2021. p. 1027. ISBN 978-0857114105.

- ↑ "Iressa". Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ↑ "Iressa Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ↑ Tan CS, Gilligan D, Pacey S (September 2015). "Treatment approaches for EGFR-inhibitor-resistant patients with non-small-cell lung cancer". The Lancet. Oncology. 16 (9): e447–e459. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00246-6. PMID 26370354. Archived from the original on 2020-07-17. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- ↑ Ko B, Paucar D, Halmos B (2017). "EGFR T790M: revealing the secrets of a gatekeeper". Lung Cancer: Targets and Therapy. 8: 147–159. doi:10.2147/LCTT.S117944. PMC 5640399. PMID 29070957.

- ↑ Yun CH, Mengwasser KE, Toms AV, Woo MS, Greulich H, Wong KK, et al. (February 2008). "The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (6): 2070–5. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.2070Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.0709662105. PMC 2538882. PMID 18227510.

- ↑ Kwak EL, Sordella R, Bell DW, Godin-Heymann N, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. (May 2005). "Irreversible inhibitors of the EGF receptor may circumvent acquired resistance to gefitinib". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (21): 7665–70. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.7665K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0502860102. PMC 1129023. PMID 15897464.

- ↑ O'Reilly LA, Kruse EA, Puthalakath H, Kelly PN, Kaufmann T, Huang DC, Strasser A (July 2009). "MEK/ERK-mediated phosphorylation of Bim is required to ensure survival of T and B lymphocytes during mitogenic stimulation". Journal of Immunology. 183 (1): 261–9. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0803853. PMC 2950174. PMID 19542438.

- ↑ Lavacchi D, Mazzoni F, Giaccone G (2019). "Clinical evaluation of dacomitinib for the treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): current perspectives". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 13: 3187–3198. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S194231. PMC 6735534. PMID 31564835.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Rossi S, ed. (2004). Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 0-9578521-4-2.

- ↑ Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, Doherty J, Politi K, Sarkaria I, et al. (September 2004). "EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from "never smokers" and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (36): 13306–11. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10113306P. doi:10.1073/pnas.0405220101. PMC 516528. PMID 15329413.

- ↑ Sordella R, Bell DW, Haber DA, Settleman J (August 2004). "Gefitinib-sensitizing EGFR mutations in lung cancer activate anti-apoptotic pathways". Science. 305 (5687): 1163–7. Bibcode:2004Sci...305.1163S. doi:10.1126/science.1101637. PMID 15284455. S2CID 34389318.

- ↑ Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, Gurubhagavatula S, Okimoto RA, Brannigan BW, et al. (May 2004). "Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (21): 2129–39. doi:10.1056/nejmoa040938. PMID 15118073. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-21. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- ↑ Takimoto CH, Calvo E. "Principles of Oncologic Pharmacotherapy" Archived 2009-05-15 at the Wayback Machine in Pazdur R, Wagman LD, Camphausen KA, Hoskins WJ (Eds) Cancer Management: A Multidisciplinary Approach Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine. 11 ed. 2008.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "IRESSA (gefitinib) Tablets. 5-2-03" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-03-31. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- ↑ "Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers - Gefitinib (marketed as Iressa) Information". Center for Drug Evaluation Research. 3 November 2018. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ↑ Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, et al. (September 2009). "Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (10): 947–57. doi:10.1056/nejmoa0810699. PMID 19692680.

- ↑ Sebastian M, Schmittel A, Reck M (March 2014). "First-line treatment of EGFR-mutated nonsmall cell lung cancer: critical review on study methodology". European Respiratory Review. 23 (131): 92–105. doi:10.1183/09059180.00008413. PMID 24591666.

- ↑ "PHARMAC funds new targeted lung cancer drug" (PDF) (Media release). PHARMAC. July 10, 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 27, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Press Announcements - FDA approves targeted therapy for first-line treatment of patients with a type of metastatic lung cancer". Archived from the original on 2018-01-26. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- ↑ Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, et al. (September 2009). "Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (10): 947–57. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. PMID 19692680.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- "Gefitinib". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 2021-09-01. Retrieved 2021-08-30.

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drug has EMA link

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- All articles with vague or ambiguous time

- Vague or ambiguous time from August 2015

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2011

- Receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- Morpholines

- Quinazolines

- Chloroarenes

- Fluoroarenes

- Amines

- Phenol ethers

- AstraZeneca brands

- RTT

- World Health Organization essential medicines (alternatives)