Atrophic vaginitis

| Atrophic vaginitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Vulvovaginal atrophy,[1] vaginal atrophy,[1] genitourinary syndrome of menopause,[1] estrogen deficient vaginitis[2] | |

| |

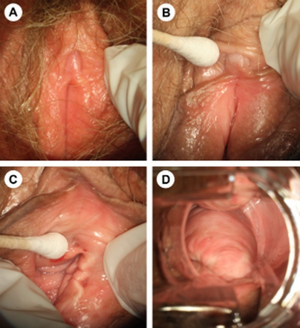

| Atrophy of the vulva, clitoris, and vagina. (A) Note pale, dry, shiny vulvar tissue and loss of fat in the labia majora and labia minora. (B) The prepuce and clitoris are often pale and reduced in size (C) The introitus may be narrowed and friable. (D) The vaginal walls lack rugae and may be pale or red. | |

| Specialty | Gynecology |

| Symptoms | Pain with sex, vaginal itchiness or dryness, burning with urination, an urge to urinate[3] |

| Complications | Urinary tract infections[1] |

| Duration | Long term[1] |

| Causes | Lack of estrogen[1] |

| Risk factors | Menopause, breastfeeding, certain medications[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Infectious vaginitis, vulvar cancer, contact dermatitis[2] |

| Treatment | Vaginal estrogen[1] |

| Frequency | Half of women (after menopause)[1] |

Atrophic vaginitis is inflammation of the vagina as a result of tissue thinning due to not enough estrogen.[2] Symptoms may include pain with sex, vaginal itchiness or dryness, and an urge to urinate or burning with urination.[3] It generally does not resolve without ongoing treatment.[1] Complications may include urinary tract infections, reduced enjoyment of sex as well as of life.[1]

The lack of estrogen typically occurs following menopause.[1] Other causes may include when breastfeeding or as a result of specific medications.[1] Risk factors include smoking.[2] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms.[1] Other conditions that may give similar symptoms include lichen planus, lichen sclerosus, eczema, thrush, vulvodynia, inflammatory vaginitis without atrophy, vulvar cancer, infections including sexually transmitted ones, and urogenital dysfunction.[4]

Treatment is generally with a vaginal lubricant or estrogen cream or tablets in the vagina.[1] [5] It is recommended that soaps and other irritants are avoided.[2] Up to half of postmenopausal women are affected.[1] Of these, about 25% do not seek medical attention.[2]

Signs and symptoms

After menopause the vaginal epithelium changes and becomes a few layers thick.[6] Many of the signs and symptoms that accompany menopause occur in atrophic vaginitis.[7] Genitourinary symptoms include

- dryness[7][8]

- pain[7][8]

- itching[7][1]

- burning[7][8]

- soreness

- pressure

- white discharge

- malodorous discharge due to infection

- painful sexual intercourse

- bleeding after intercourse[9]

- painful urination[7]

- blood in the urine

- increased urinary frequency[7][8]

- incontinence

- increased susceptibility to infections[7]

- decreased vaginal lubrication[8]

- urinary tract infections[1][8]

- painful urination[8]

- difficulty sitting[1]

- difficulty wiping[1]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based upon the symptoms that cannot be better accounted for by another diagnosis.[8] Lab tests usually do not provide information that will aid in diagnosing. A visual exam is useful. The observations of the following may indicate lower estrogen levels: little pubic hair, loss of the labial fat pad, thinning and resorption of the labia minora, and the narrowing of the vaginal opening. An internal exam will reveal the presence of low vaginal muscle tone, the lining of the vagina appears smooth, shiny, pale with loss of folds. The cervical fornices may have disappeared and the cervix can appear flush with the top of the vagina. Inflammation is apparent when the vaginal lining bleeds easily and appears swollen.[1] The vaginal pH will be measured at 4.5 and higher.[10]

Treatment

Symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) will unlikely be resolved without treatment.[1] Women may have many or a few symptoms so treatment is provided that best suits each woman. If other health problems are also present, these can be taken into account when determining the best course of treatment. For those who have symptoms related to sexual activities, a lubricant may be sufficient.[1][11] If both urinary and genital symptoms exist, local, low-dose estrogen therapy can be effective. Those women who are survivors of hormone-sensitive cancer may need to be treated more cautiously.[1] Some women can have symptoms that are widespread and may be at risk for osteoporosis. Estrogen and adjuvants may be best.[11]

Topical treatment with estrogen is effective when the symptoms are severe and relieves the disruption in pH to restore the microbiome of the vagina. When symptoms include those related to the urinary system, systematic treatment can be used. Recommendations for the use of the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration help to prevent adverse endometrial effects.[11]

Some treatments have been developed more recently. These include selective estrogen receptor modulators, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone, and laser therapy. Other treatments are available without a prescription such as vaginal lubricants and moisturizers. Vaginal dilators may be helpful. Since GSM may also cause urinary problems related to pelvic floor dysfunction, a woman may benefit from pelvic floor strengthening exercises. Women and their partners have reported that estrogen therapy resulted in less painful sex, more satisfaction with sex, and an improvement in their sex life.[1]

Epidemiology

Up to 50% of postmenopausal women have at least some degree of vaginal atrophy. It is often underdiagnosed and undertreated.[1]

Terminology

Vulvovaginal atrophy, and atrophic vaginitis have been the preferred terms for this condition and cluster of symptoms until recently. These terms are now regarded as inaccurate in describing changes to the entire genitourinary system occurring after menopause. The term atrophic vaginitis suggests that the vagina is inflamed or infected. Though this may be true, inflammation and infection are not the major components of postmenopausal changes to the vagina. The former terms do not describe the negative effects on the lower urinary tract which can be the most troubling symptoms of menopause for women.[7] Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) was determined to be more accurate than vulvovaginal atrophy by two professional societies.[1][8][12] The term atrophic vaginitis does not reflect the related changes of the labia, clitoris, vestibule, urethra and bladder.[8]

Research

The FDA has approved the use of lasers in the treatment of many disorders. The treatment of GSM is not specifically mentioned in the list of disorders by the United States' Food and Drug Administration (FDA) but laser treatments have had success. Larger studies are still needed. The laser treatment works by resurfacing the vaginal epithelium and activating growth factors that increases blood flow, deposition of collage and the thickness of the vaginal lining. Women treated with laser therapy reported diminished symptoms of dryness, burning, itching, pain during sexual intercourse, and painful urination. Few adverse effects were noted.[1]

In 2018, the FDA issued a warning that lasers and other high energy devices were not approved for this application and it had received multiple reports of injuries.[13]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 Faubion, SS; Sood, R; Kapoor, E (December 2017). "Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause: Management Strategies for the Clinician". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 92 (12): 1842–1849. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.08.019. PMID 29202940.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Ferri, Fred F. (2016). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1331. ISBN 9780323448383. Archived from the original on 2018-10-15. Retrieved 2018-10-15.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "9. Tumours of the vagina: Atrophic vaginitis". Female genital tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 4 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. p. 394. ISBN 978-92-832-4504-9. Archived from the original on 2022-06-17. Retrieved 2022-09-03.

- ↑ Flores, Shelley A.; Hall, Carrie A. (2021). "Atrophic Vaginitis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 33232011. Archived from the original on 2022-09-20. Retrieved 2022-09-05.

- ↑ Ton, Joey (10 June 2019). "#237 Verifying the value of vaginal estradiol tablets". CFPCLearn. Archived from the original on 28 March 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- ↑ Karl Knörr, Henriette Knörr-Gärtner, Fritz K. Beller, Christian Lauritzen (2013), Geburtshilfe und Gynäkologie: Physiologie und Pathologie der Reproduktion (in German) (3. ed.), Berlin: Springer, pp. 24–25, ISBN 978-3-642-95584-6

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Kim, HK; Kang, SY; Chung, YJ; Kim, JH; Kim, MR (August 2015). "The Recent Review of the Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause". Journal of Menopausal Medicine. 21 (2): 65–71. doi:10.6118/jmm.2015.21.2.65. PMC 4561742. PMID 26357643.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 Portman, D.J.; Gass, M.L.S. (November 2014). "Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: New terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and The North American Menopause Society". Maturitas. 79 (3): 349–354. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.07.013. PMID 25179577.

- ↑ Choices, N. H. S. (2018). "What causes a woman to bleed after sex? - Health questions - NHS Choices". Archived from the original on 2018-02-05. Retrieved 2018-02-07.

- ↑ "Vaginal Wet Mount". WebMD. Archived from the original on 2018-02-10. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "The Best Treatments for Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause". www.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-04. Retrieved 2018-02-07.

- ↑ International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and the Board of Trustees of The North American Menopause Society

- ↑ "FDA warning shines light on vaginal rejuvenation". www.mdedge.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |