Zopiclone

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | zoe-PIK-lone |

| Trade names | Imovane, Zimovane, Dopareel, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Z-drug |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth (tablet, 3.75 mg or 7.5mg (UK), 5 mg, 7.5 mg, or 10 mg (JP) |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Legal | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 75-80%[2] |

| Protein binding | 52–59% |

| Metabolism | Liver through CYP3A4 and CYP2E1 |

| Elimination half-life | ~5 hours (3.5–6.5 hours) ~7–9 hours for age 65+ |

| Excretion | Urine (80%) |

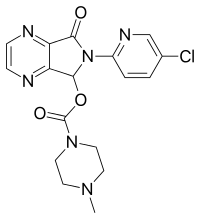

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H17ClN6O3 |

| Molar mass | 388.81 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Zopiclone, sold under the brand name Imovane among others, is a medication used to treat difficulty sleeping.[3] Zopiclone is only recommended for short-term use, usually no more than a week or two.[4] It is taken by mouth.[5]

Side effects include decreased cognitive function, the body becoming accustomed to the effects (tolerance), rapid return of trouble sleeping when stopped, falls, and addiction.[3] Other side effects include a dry mouth and behavioral changes.[5] Use is not recommended in people with significant sleep apnea.[5] Withdrawal symptoms may occur if rapidly stopped.[5] Use is not recommended during pregnancy, specifically late pregnacy as such use may result in problems in the baby at birth.[5] Use is also not recommended when breastfeeding.[5] Zopiclone is a sedative and Z-drug.[4] It works via the benzodiazepine receptor.[6]

Zopiclone was developed in 1985.[6] It became commercially avaliable in Canada in 1990.[7] In the United Kingdom it is avaliable as a generic medication and a months supply costs the NHS about a pound as of 2020.[5] In the United States, zopiclone is not commercially available, although eszopiclone.[8] Zopiclone is a controlled substance in the United States and the United Kingdom.[8][5]

Medical uses

Zopiclone is used for the short-term treatment of insomnia where sleep initiation or sleep maintenance are prominent symptoms. Long-term use is not recommended, as tolerance, dependence, and addiction can occur.[9][10] One low-quality study found that zopiclone is ineffective in improving sleep quality or increasing sleep time in shift workers - more research in this area has been recommended.[11]

Elderly

A review of the management of insomnia in the elderly found evidence for nondrug treatments. Compared with the benzodiazepines, zopiclone, offer few if any advantages in efficacy or tolerability. Agents such as the melatonin receptor agonists may be more suitable for chronic insomnia in elderly people. Long-term use of sedative-hypnotics for insomnia lacks evidence is discouraged for reasons that include concerns about side effects.[12] In addition, the effectiveness and safety of long-term use of nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic drugs remains to be determined.[12]

Liver disease

People with liver disease eliminate zopiclone much more slowly and experience increased effects.[13]

Dosage

The typical dose is 7.5 mg once per day just before bed.[5] In older people, those with mild or moderate liver problems, those with kidney problems, and those with breathing problems half that dose should be used.[5]

Side effects

Sleeping pills, including zopiclone, have been associated with an increased risk of death.[14] The British National Formulary states adverse reactions as follows: "taste disturbance (some report a metallic like taste); less commonly nausea, vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness, dry mouth, headache; rarely amnesia, confusion, depression, hallucinations, nightmares; very rarely light headedness, incoordination, paradoxical effects [...] and sleep-walking also reported".[15]

People muscle weakness due to myasthenia gravis or have poor respiratory reserves due to severe chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or other lung disease, nor can a people with any untreated abnormality of the thyroid gland.[16]

Zopiclone causes impaired driving skills similar to those of benzodiazepines. Long-term users of hypnotic drugs for sleep disorders develop only partial tolerance to adverse effects on driving with users of hypnotic drugs even after 1 year of use still showing an increased motor vehicle accident rate.[17] Patients who drive motor vehicles should not take zopiclone unless they stop driving due to a significant increased risk of accidents in zopiclone users.[18] Zopiclone induces impairment of psychomotor function.[19][20] Driving or operating machinery should be avoided after taking zopiclone as effects can carry over to the next day, including impaired hand eye coordination.[21][22]

Sleep

It causes similar alterations on EEG readings and sleep architecture as benzodiazepines and causes disturbances in sleep architecture on withdrawal.[23][24] Zopiclone reduces both delta waves and the number of high-amplitude delta waves whilst increasing low-amplitude waves.[25] Zopiclone reduces the total amount of time spent in REM sleep as well as delaying its onset.[26][27] Cognitive behavioral therapy has been found to be superior to zopiclone in the treatment of insomnia and has been found to have lasting effects on sleep quality for at least a year after therapy.[28][29][30][31]

Elderly

Zopiclone, similar to other benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic drugs, causes impairments in body balance and standing steadiness in individuals who wake up at night or the next morning. Falls and hip fractures are frequently reported. The combination with alcohol consumption increases these impairments. Partial, but incomplete tolerance develops to these impairments.[32] Zopiclone increases postural sway and increases the number of falls in older people, as well as cognitive side effects. Falls are a significant cause of death in older people.[33][34][35]

Other side effects include cognitive impairment (anterograde amnesia), daytime sedation, motor incoordination, and increased risk of motor vehicle accidents and falls.[12]

Overdose

Zopiclone is sometimes used as a method of suicide.[36] It has a similar fatality index to that of benzodiazepine drugs, apart from temazepam, which is particularly toxic in overdose.[37][38][39] Deaths have occurred from zopiclone overdose, alone or in combination with other drugs.[40][41][42] Overdose of zopiclone may present with excessive sedation and depressed respiratory function that may progress to coma and possibly death.[43] Zopiclone combined with alcohol, opiates, or other central nervous system depressants may be even more likely to lead to fatal overdoses. Zopiclone overdosage can be treated with the benzodiazepine receptor antagonist flumazenil, which displaces zopiclone from its binding site on the benzodiazepine receptor, thereby rapidly reversing its effects.[44][45] Serious effects on the heart may also occur from a zopiclone overdose[46][47] when combined with piperazine.[48]

Death certificates show the number of zopiclone-related deaths is on the rise.[49] When taken alone, it usually is not fatal, but when mixed with alcohol or other drugs such as opioids, or in patients with respiratory, or hepatic disorders, the risk of a serious and fatal overdose increases.[50][51]

Interactions

Zopiclone also interacts with trimipramine and caffeine.[52][53]

Alcohol has an additive effect when combined with zopiclone, enhancing the adverse effects including the overdose potential of zopiclone significantly.[54][55] Due to these risks and the increased risk for dependence, alcohol should be avoided when using zopiclone.[54]

Erythromycin appears to increase the absorption rate of zopiclone and prolong its elimination half-life, leading to increased plasma levels and more pronounced effects. Itraconazole has a similar effect on zopiclone pharmacokinetics as erythromycin. The elderly may be particularly sensitive to the erythromycin and itraconazole drug interaction with zopiclone. Temporary dosage reduction during combined therapy may be required, especially in the elderly.[56][57] Rifampicin causes a very notable reduction in half-life of zopiclone and peak plasma levels, which results in a large reduction in the hypnotic effect of zopiclone. Phenytoin and carbamazepine may also provoke similar interactions.[58] Ketoconazole and sulfaphenazole interfere with the metabolism of zopiclone.[59] Nefazodone impairs the metabolism of zopiclone leading to increased zopiclone levels and marked next-day sedation.[60]

Pharmacology

Zopiclone is molecularly distinct from benzodiazepine drugs and is classed as a cyclopyrrolone. However, zopiclone increases the normal transmission of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the central nervous system, via modulating benzodiazepine receptors in the same way that benzodiazepine drugs do.

The therapeutic pharmacological properties of zopiclone include hypnotic, anxiolytic, anticonvulsant, and myorelaxant properties.[61] Zopiclone and benzodiazepines bind to the same sites on GABAA-containing receptors, causing an enhancement of the actions of GABA to produce the therapeutic and adverse effects of zopiclone. The metabolite of zopiclone called desmethylzopiclone is also pharmacologically active, although it has predominately anxiolytic properties. One study found some slight selectivity for zopiclone on α1 and α5 subunits,[62] although it is regarded as being unselective in its binding to α1, α2, α3, and α5 GABAA benzodiazepine receptor complexes. Desmethylzopiclone has been found to have partial agonist properties, unlike the parent drug zopiclone, which is a full agonist.[63] The mechanism of action of zopiclone is similar to benzodiazepines, with similar effects on locomotor activity and on dopamine and serotonin turnover.[64][65] A meta-analysis of randomised controlled clinical trials that compared benzodiazepines to zopiclone or other Z drugs such as zolpidem and zaleplon has found few clear and consistent differences between zopiclone and the benzodiazepines in sleep onset latency, total sleep duration, number of awakenings, quality of sleep, adverse events, tolerance, rebound insomnia, and daytime alertness.[66] Zopiclone is in the cyclopyrrolone family of drugs. Other cyclopyrrolone drugs include suriclone. Zopiclone, although molecularly different from benzodiazepines, shares an almost identical pharmacological profile as benzodiazepines, including anxiolytic properties. Its mechanism of action is by binding to the benzodiazepine site and acting as a full agonist, which in turn positively modulates benzodiazepine-sensitive GABAA receptors and enhances GABA binding at the GABAA receptors to produce zopiclone's pharmacological properties.[67][68][69] In addition to zopiclone's benzodiazepine pharmacological properties, it also has some barbiturate-like properties.[70][71]

In EEG studies, zopiclone significantly increases the energy of the beta frequency band and shows characteristics of high-voltage slow waves, desynchronization of hippocampal theta waves, and an increase in the energy of the delta frequency band. Zopiclone increases both stage 2 and slow-wave sleep (SWS), while zolpidem, an α1-selective compound, increases only SWS and causes no effect on stage 2 sleep. Zopiclone is less selective to the α1 site and has higher affinity to the α2 site than zaleplon. Zopiclone is therefore very similar pharmacologically to benzodiazepines.[72]

Pharmacokinetics

After oral administration, zopiclone is rapidly absorbed, with a bioavailability around 75–80%. Time to peak plasma concentration is 1–2 hours. A high-fat meal preceding zopiclone administration does not change absorption (as measured by AUC), but reduces peak plasma levels and delays its occurrence, thus may delay the onset of therapeutic effects.

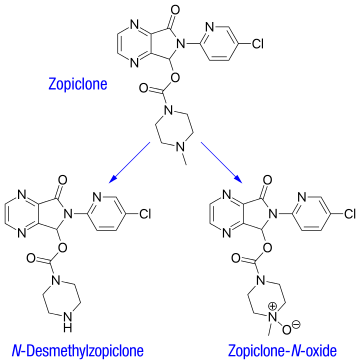

The plasma protein-binding of zopiclone has been reported to be weak, between 45 and 80% (mean 52–59%). It is rapidly and widely distributed to body tissues, including the brain, and is excreted in urine, saliva, and breast milk. Zopiclone is partly extensively metabolized in the liver to form an active N-demethylated derivative (N-desmethylzopiclone) and an inactive zopiclone-N-oxide. Hepatic enzymes playing the most significant role in zopiclone metabolism are CYP3A4 and CYP2E1. In addition, about 50% of the administered dose is decarboxylated and excreted via the lungs. In urine, the N-demethyl and N-oxide metabolites account for 30% of the initial dose. Between 7 and 10% of zopiclone is recovered from the urine, indicating extensive metabolism of the drug before excretion. The terminal elimination half-life of zopiclone ranges from 3.5 to 6.5 hours (5 hours on average).[2]

The pharmacokinetics of zopiclone in humans are stereoselective. After oral administration of the racemic mixture, Cmax (time to maximum plasma concentration), area under the plasma time-concentration curve (AUC) and terminal elimination half-life values are higher for the dextrorotatory enantiomers, owing to the slower total clearance and smaller volume of distribution (corrected by the bioavailability), compared with the levorotatory enantiomer. In urine, the concentrations of the dextrorotatory enantiomers of the N-demethyl and N-oxide metabolites are higher than those of the respective antipodes.

The pharmacokinetics of zopiclone are altered by aging and are influenced by renal and hepatic functions.[73] In severe chronic kidney failure, the area under the curve value for zopiclone was larger and the half-life associated with the elimination rate constant longer, but these changes were not considered to be clinically significant.[74] Sex and race have not been found to interact with pharmacokinetics of zopiclone.[2]

Chemistry

The melting point of zopiclone is 178 °C.[75] Zopiclone's solubility in water, at room temperature (25 °C) are 0.151 mg/mL.[75] The logP value of zopiclone is 0.8.[75]

Detection

Zopiclone may be measured in blood, plasma, or urine by chromatographic methods. Plasma concentrations are typically less than 100 μg/l during therapeutic use, but frequently exceed 100 μg/l in automotive vehicle operators arrested for impaired driving ability and may exceed 1000 μg/l in acutely poisoned patients. Post mortem blood concentrations are usually in a range of 0.4-3.9 mg/l in victims of fatal acute overdose.[76][77][78]

History

Zopiclone was developed and first introduced in 1986 by Rhône-Poulenc S.A., now part of Sanofi-Aventis, the main worldwide manufacturer. Initially, it was promoted as an improvement on benzodiazepines, but a recent meta-analysis found it was no better than benzodiazepines in any of the aspects assessed.[79] On April 4, 2005, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration listed zopiclone under schedule IV, due to evidence that the drug has addictive properties similar to benzodiazepines.

Zopiclone, as traditionally sold worldwide, is a racemic mixture of two stereoisomers, only one of which is active.[80][81] In 2005, the pharmaceutical company Sepracor of Marlborough, Massachusetts began marketing the active stereoisomer eszopiclone under the name Lunesta in the United States. This had the consequence of placing what is a generic drug in most of the world under patent control in the United States. Generic forms of Lunesta have since become available in the United States. Zopiclone is currently available off-patent in a number of European countries, as well as Brazil, Canada, and Hong Kong. The eszopiclone/zopiclone difference is in the dosage—the strongest eszopiclone dosage contains 3 mg of the therapeutic stereoisomer, whereas the highest zopiclone dosage (10 mg) contains 5 mg of the active stereoisomer[citation needed]. The two agents have not yet been studied in head-to-head clinical trials to determine the existence of any potential clinical differences (efficacy, side effects, developing dependence on the drug, safety, etc.).

Society and culture

Recreational use

Zopiclone has the potential for misuse and dosage escalation, drug abuse, and drug dependence. It is abused orally and sometimes intravenously, and often combined with alcohol to achieve a combined sedative hypnotic—alcohol euphoria. Patients abusing the drug are also at risk of dependence. Withdrawal symptoms can be seen after long-term use of normal doses even after a gradual reduction regimen. The Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties recommends zopiclone prescriptions not exceed 7 to 10 days, owing to concerns of addiction, tolerance, and physical dependence.[82] Two types of drug misuse can occur: either recreational misuse, wherein the drug is taken to achieve a high, or when the drug is continued long-term against medical advice.[83][84] Zopiclone may be more addictive than benzodiazepines.[85] Those with a history of substance misuse or mental health disorders may be at an increased risk of high-dose zopiclone misuse.[86] High dose misuse of zopiclone and increasing popularity amongst drug abusers who have been prescribed with zopiclone[87] The symptoms of zopiclone addiction can include depression, dysphoria, hopelessness, slow thoughts, social isolation, worrying, sexual anhedonia, and nervousness.[88]

Zopiclone and other sedative hypnotic drugs are detected frequently in cases of people suspected of driving under the influence of drugs. Other drugs, including the benzodiazepines and zolpidem, are also found in high numbers of suspected drugged drivers. Many drivers have blood levels far exceeding the therapeutic dose range and often in combination with other alcohol, illegal, or prescription drugs of abuse, suggesting a high degree of abuse potential for benzodiazepines, zolpidem, and zopiclone.[89][90] Zopiclone, which at prescribed doses causes moderate impairment the next day, has been estimated to increase the risk of vehicle accidents by 50%, causing an increase of 503 excess accidents per 100,000 persons. Zaleplon or other nonimpairing sleep aids were recommended be used instead of zopiclone to reduce traffic accidents.[91] Zopiclone as with other hypnotic drugs is sometimes abused to carry out criminal acts such as sexual assaults.[92]

Zopiclone has crosstolerance with barbiturates and is able to suppress barbiturate withdrawal signs. It is frequently self-administered intravenously in studies on monkeys, suggesting a high risk of abuse potential.[93]

Zopiclone is in the top ten medications obtained using a false prescription in France.[2]

References

- ↑ Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Justice (April 2005). "Schedules of controlled substances: placement of zopiclone into schedule IV. Final rule" (PDF). Fed Regist. 70 (63): 16935–16937. PMID 15806735. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-05-06. Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Assessment of Zopiclone" (PDF). World Health Organization. Essential Medicines and Health Products. World Health Organization. 2006. p. 9 (Section 5. Pharmacokinetics). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Atkin, Tobias; Comai, Stefano; Gobbi, Gabriella (April 2018). "Drugs for Insomnia beyond Benzodiazepines: Pharmacology, Clinical Applications, and Discovery". Pharmacological Reviews. 70 (2): 197–245. doi:10.1124/pr.117.014381. PMID 29487083.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 BNF 79 : March 2020. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society. 2020. p. 504. ISBN 9780857113658.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ravina, Enrique (2011). The Evolution of Drug Discovery: From Traditional Medicines to Modern Drugs. John Wiley & Sons. p. 68. ISBN 978-3-527-32669-3. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ Holbrook, AM; Crowther, R; Lotter, A; Cheng, C; King, D (25 January 2000). "Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 162 (2): 225–33. PMID 10674059.

{{cite journal}}: Missing pipe in:|journal=(help) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Zopiclone consumer information from". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ↑ "What's wrong with prescribing hypnotics?". Drug Ther Bull. 42 (12): 89–93. December 2004. doi:10.1136/dtb.2004.421289. PMID 15587763. S2CID 40188442.

- ↑ Touitou Y (July 2007). "[Sleep disorders and hypnotic agents: medical, social and economical impact]". Ann Pharm Fr (in French). 65 (4): 230–238. doi:10.1016/s0003-4509(07)90041-3. PMID 17652991.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Liira, Juha; Verbeek, Jos H.; Costa, Giovanni; Driscoll, Tim R.; Sallinen, Mikael; Isotalo, Leena K.; Ruotsalainen, Jani H. (2014). "Pharmacological interventions for sleepiness and sleep disturbances caused by shift work". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD009776. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009776.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 25113164. Archived from the original on 2021-02-02. Retrieved 2019-01-09.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Bain KT (June 2006). "Management of chronic insomnia in elderly persons". Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 4 (2): 168–192. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2006.06.006. PMID 16860264.

- ↑ Parker, G; Roberts, Cj (September 1983). "Plasma concentrations and central nervous system effects of the new hypnotic agent zopiclone in patients with chronic liver disease". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 16 (3): 259–265. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1983.tb02159.x. ISSN 0306-5251. PMC 1428012. PMID 6626417.

- ↑ Kripke, DF (February 2016). "Mortality Risk of Hypnotics: Strengths and Limits of Evidence" (PDF). Drug Safety. 39 (2): 93–107. doi:10.1007/s40264-015-0362-0. PMID 26563222. S2CID 7946506. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-14. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- ↑ "Zopiclone", British National Formulary, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 19 September 2016, archived from the original on 9 October 2016, retrieved 2 October 2016

- ↑ Upfal, Jonathan (2000) [1991]. The Australian Drug Guide (5 ed.). Melbourne: Bookman Press Pty Ltd. p. 743. ISBN 978-1-86395-170-8.

- ↑ Staner L, Ertlé S, Boeijinga P, et al. (October 2005). "Next-day residual effects of hypnotics in DSM-IV primary insomnia: a driving simulator study with simultaneous electroencephalogram monitoring". Psychopharmacology. 181 (4): 790–798. doi:10.1007/s00213-005-0082-8. PMID 16025317. S2CID 26351598.

- ↑ Barbone F, McMahon AD, Davey PG, et al. (October 1998). "Association of road-traffic accidents with benzodiazepine use". Lancet. 352 (9137): 1331–1336. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04087-2. PMID 9802269. S2CID 40825194. Archived from the original on 2014-11-10. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ Yasui M; Kato A; Kanemasa T; Murata S; Nishitomi K; Koike K; Tai N; Shinohara S; Tokomura M; Horiuchi M; Abe K (June 2005). "[Pharmacological profiles of benzodiazepinergic hypnotics and correlations with receptor subtypes]". Nihon Shinkei Seishin Yakurigaku Zasshi. 25 (3): 143–151. PMID 16045197.

- ↑ Rettig, Hc; De, Haan, P; Zuurmond, Ww; Von, Leeuwen, L (December 1990). "Effects of hypnotics on sleep and psychomotor performance. A double-blind randomised study of lormetazepam, midazolam and zopiclone". Anaesthesia. 45 (12): 1079–1082. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1990.tb14896.x. ISSN 0003-2409. PMID 2278337.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Lader, M; Denney, Sc (1982). "A double-blind study to establish the residual effects of zopiclone on performance in healthy volunteers". International Pharmacopsychiatry. 17 Suppl 2: 98–108. ISSN 0020-8272. PMID 7188379.

- ↑ Billiard, M; Besset, A; De, Lustrac, C; Brissaud, L (1987). "Dose-response effects of zopiclone on night sleep and on nighttime and daytime functioning". Sleep. 10 Suppl 1: 27–34. doi:10.1093/sleep/10.suppl_1.27. ISSN 0161-8105. PMID 3326113.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Trachsel L, Dijk DJ, Brunner DP, Klene C, Borbély AA (February 1990). "Effect of zopiclone and midazolam on sleep and EEG spectra in a phase-advanced sleep schedule". Neuropsychopharmacology. 3 (1): 11–18. PMID 2306331.

- ↑ Mann K, Bauer H, Hiemke C, Röschke J, Wetzel H, Benkert O (August 1996). "Acute, subchronic and discontinuation effects of zopiclone on sleep EEG and nocturnal melatonin secretion". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 6 (3): 163–168. doi:10.1016/0924-977X(96)00014-4. PMID 8880074. S2CID 25259646.

- ↑ Wright NA, Belyavin A, Borland RG, Nicholson AN (June 1986). "Modulation of delta activity by hypnotics in middle-aged subjects: studies with a benzodiazepine (flurazepam) and a cyclopyrrolone (zopiclone)". Sleep. 9 (2): 348–352. doi:10.1093/sleep/9.2.348. PMID 3505734.

- ↑ Kim YD, Zhuang HY, Tsutsumi M, Okabe A, Kurachi M, Kamikawa Y (October 1993). "Comparison of the effect of zopiclone and brotizolam on sleep EEG by quantitative evaluation in healthy young women". Sleep. 16 (7): 655–661. doi:10.1093/sleep/16.7.655. PMID 8290860.

- ↑ Kanno O, Watanabe H, Kazamatsuri H (March 1993). "Effects of zopiclone, flunitrazepam, triazolam and levomepromazine on the transient change in sleep-wake schedule: polygraphic study, and the evaluation of sleep and daytime condition". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 17 (2): 229–239. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(93)90044-S. PMID 8430216.

- ↑ "Cognitive therapy superior to zopiclone for insomnia". J Fam Pract. 55 (10): 845. October 2006. PMID 17089469.

- ↑ Baillargeon L, Landreville P, Verreault R, Beauchemin JP, Grégoire JP, Morin CM (November 2003). "Discontinuation of benzodiazepines among older insomniac adults treated with cognitive-behavioural therapy combined with gradual tapering: a randomized trial". CMAJ. 169 (10): 1015–1020. PMC 236226. PMID 14609970. Archived from the original on 2011-06-10. Retrieved 2008-12-24.

- ↑ Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, et al. (June 2006). "Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA. 295 (24): 2851–2858. doi:10.1001/jama.295.24.2851. PMID 16804151.

- ↑ Morgan K; Dixon S; Mathers N; Thompson J; Tomeny M (February 2004). "Psychological treatment for insomnia in the regulation of long-term hypnotic drug use" (PDF). Health Technol Assess. 8 (8): iii–iv, 1–68. doi:10.3310/hta8080. PMID 14960254. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-11-16. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ↑ Mets, M.A.; Volkerts, E.R.; Olivier, B.; Verster, J.C. (February 2010). "Effect of hypnotic drugs on body balance and standing steadiness". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 14 (4): 259–267. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.008. PMID 20171127.

- ↑ Tada, K; Sato, Y; Sakai, T; Ueda, N; Kasamo, K; Kojima, T (1994). "Effects of zopiclone, triazolam, and nitrazepam on standing steadiness". Neuropsychobiology. 29 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1159/000119057. ISSN 0302-282X. PMID 8127419.

- ↑ Allain H, Bentué-Ferrer D, Tarral A, Gandon JM (July 2003). "Effects on postural oscillation and memory functions of a single dose of zolpidem 5 mg, zopiclone 3.75 mg and lormetazepam 1 mg in elderly healthy subjects. A randomized, cross-over, double-blind study versus placebo". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 59 (3): 179–188. doi:10.1007/s00228-003-0591-5. PMID 12756510. S2CID 13440208.

- ↑ Antai-Otong D (August 2006). "The art of prescribing. Risks and benefits of non-benzodiazepine receptor agonists in the treatment of acute primary insomnia in older adults". Perspect Psychiatr Care. 42 (3): 196–200. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2006.00070.x. PMID 16916422.

- ↑ Mannaert E, Tytgat J, Daenens P (November 1996). "Detection and quantification of the hypnotic zopiclone, connected with an uncommon case of drowning". Forensic Science International. 83 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(96)02018-X. PMID 8939015.

- ↑ Buckley, N. A.; Dawson, A. H.; Whyte, I. M.; O'Connell, D. L. (1995). "Relative toxicity of benzodiazepines in overdose". BMJ. 310 (6974): 219–221. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6974.219. PMC 2548618. PMID 7866122.

- ↑ Buckley NA, Dawson AH, Whyte IM, McManus P, Ferguson N.Correlations between prescriptions and drugs taken in self-poisoning: Implications for prescribers and drug regulation.Med J Aust (in press)

- ↑ Buckley NA, Dawson AH, Whyte IM, O'Connell DL (1995). "[Relative toxicity of benzodiazepines in overdose.]". BMJ. 310 (6974): 219–221. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6974.219. PMC 2548618. PMID 7866122.

- ↑ Meatherall RC (March 1997). "Zopiclone fatality in a hospitalized patient". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 42 (2): 340–343. doi:10.1520/JFS14125J. PMID 9068198.

- ↑ Van Bocxlaer J, Meyer E, Clauwaert K, Lambert W, Piette M, De Leenheer A (1996). "Analysis of zopiclone (Imovane) in postmortem specimens by GC-MS and HPLC with diode-array detection". J Anal Toxicol. 20 (1): 52–54. doi:10.1093/jat/20.1.52. PMID 8837952.

- ↑ Yamazaki M, Terada M, Mitsukuni Y, Yoshimura M (August 1998). "[An autopsy case of poisoning by neuropsychopharmaceuticals including zopiclone]". Nihon Hoigaku Zasshi (in Japanese). 52 (4): 245–252. PMID 9893443.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Boniface PJ, Russell SG (1996). "Two cases of fatal zopiclone overdose". J Anal Toxicol. 20 (2): 131–133. doi:10.1093/jat/20.2.131. PMID 8868406.

- ↑ Cienki, J.J.; Burkhart K.K.; Donovan J.W. (2005). "Zopiclone overdose responsive to flumazenil". Clinical Toxicology. 43 (5): 385–386. doi:10.1081/clt-200058944. PMID 16235515. S2CID 41701825.

- ↑ Pounder, Dj; Davies, Ji (May 1994). "Zopiclone poisoning: tissue distribution and potential for postmortem diffusion". Forensic Science International. 65 (3): 177–183. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(94)90273-9. ISSN 0379-0738. PMID 8039775.

- ↑ Regouby Y, Delomez G, Tisserant A (1990). "[First-degree heart block caused by voluntary zopiclone poisoning]". Thérapie (in French). 45 (2): 162. PMID 2353332.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Regouby Y, Delomez G, Tisserant A (1989). "[Auriculo-ventricular block during voluntary poisoning with zopiclone]". Thérapie (in French). 44 (5): 379–380. PMID 2814922.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Dart, Richard C. (2003). Medical Toxicology. p. 889. ISBN 978-0-7817-2845-4.

- ↑ Carlsten, A; Waern M; Holmgren P; Allebeck P. (2003). "The role of benzodiazepines in elderly suicides". Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 31 (3): 224–228. doi:10.1080/14034940210167966. PMID 12850977. S2CID 24102880.

- ↑ Harry P (April 1997). "[Acute poisoning by new psychotropic drugs]". Rev Prat. 47 (7): 731–735. PMID 9183949.

- ↑ Bramness JG, Arnestad M, Karinen R, Hilberg T (September 2001). "Fatal overdose of zopiclone in an elderly woman with bronchogenic carcinoma". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 46 (5): 1247–1249. doi:10.1520/JFS15131J. PMID 11569575.

- ↑ Caille, G; Du Souich, P; Spenard, J; Lacasse, Y; Vezina, M (April 1984). "Pharmacokinetic and clinical parameters of zopiclone and trimipramine when administered simultaneously to volunteers". Biopharmaceutics & Drug Disposition. 5 (2): 117–125. doi:10.1002/bdd.2510050205. ISSN 0142-2782. PMID 6743780.

- ↑ Mattila, M.E.; Mattila, M.J.; Nuotto, E. (April 1992). "Caffeine moderately antagonizes the effects of triazolam and zopiclone on the psychomotor performance of healthy subjects". Pharmacology & Toxicology. 70 (4): 286–289. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1992.tb00473.x. ISSN 0901-9928. PMID 1351673.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Kuitunen T; Mattila MJ; Seppala T (April 1990). "Actions and interactions of hypnotics on human performance: single doses of zopiclone, triazolam, and alcohol". Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 5 (Suppl 2): 115–130. PMID 2201724.

- ↑ Koski A, Ojanperä I, Vuori E (May 2003). "Interaction of alcohol and drugs in fatal poisonings". Hum Exp Toxicol. 22 (5): 281–287. doi:10.1191/0960327103ht324oa. PMID 12774892. S2CID 37777007.

- ↑ Aranko, K; Luurila, H; Backman, Jt; Neuvonen, Pj; Olkkola, Kt (October 1994). "The effect of erythromycin on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zopiclone". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 38 (4): 363–367. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1994.tb04367.x. ISSN 0306-5251. PMC 1364781. PMID 7833227.

- ↑ Jalava KM, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ (1996). "Effect of itraconazole on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of zopiclone". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 51 (3–4): 331–334. doi:10.1007/s002280050207. PMID 9010708. S2CID 20916689.

- ↑ Villikka K, Kivistö KT, Lamberg TS, Kantola T, Neuvonen PJ (May 1997). "Concentrations and effects of zopiclone are greatly reduced by rifampicin". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 43 (5): 471–474. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00579.x. PMC 2042775. PMID 9159561.

- ↑ Becquemont L, Mouajjah S, Escaffre O, Beaune P, Funck-Brentano C, Jaillon P (September 1999). "Cytochrome P-450 3A4 and 2C8 are involved in zopiclone metabolism". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 27 (9): 1068–1073. PMID 10460808. Archived from the original on 2005-04-17. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ↑ Alderman CP, Gebauer MG, Gilbert AL, Condon JT (November 2001). "Possible interaction of zopiclone and nefazodone". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 35 (11): 1378–1380. doi:10.1345/aph.1A074. PMID 11724087. S2CID 38894701.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Röschke, J; Mann, K; Aldenhoff, Jb; Benkert, O (March 1994). "Functional properties of the brain during sleep under subchronic zopiclone administration in man". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 4 (1): 21–30. doi:10.1016/0924-977X(94)90311-5. ISSN 0924-977X. PMID 8204993. S2CID 40503805.

- ↑ Petroski RE, Pomeroy JE, Das R, et al. (April 2006). "Indiplon is a high-affinity positive allosteric modulator with selectivity for alpha1 subunit-containing GABAA receptors". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 317 (1): 369–377. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.096701. PMID 16399882. S2CID 46510829.

- ↑ Atack, J.R. (August 2003). "Anxioselective compounds acting at the GABA(A) receptor benzodiazepine binding site". Current Drug Targets. CNS & Neurological Disorders. 2 (4): 213–332. doi:10.2174/1568007033482841. PMID 12871032.

- ↑ Liu HJ; Sato K; Shih HC; Shibuya T; Kawamoto H; Kitagawa H. (March 1985). "Pharmacologic studies of the central action of zopiclone: effects on locomotor activity and brain monoamines in rats". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy, and Toxicology. 23 (3): 121–128. PMID 2581904.

- ↑ Sato K; Hong YL; Yang MS; Shibuya T; Kawamoto H; Kitagawa H. (April 1985). "Pharmacologic studies of central actions of zopiclone: influence on brain monoamines in rats under stressful condition". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy, and Toxicology. 23 (4): 204–210. PMID 2860074.

- ↑ Dündar, Y; Dodd S; Strobl J; Boland A; Dickson R; Walley T. (July 2004). "Comparative efficacy of newer hypnotic drugs for the short-term management of insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Human Psychopharmacology. 19 (5): 305–322. doi:10.1002/hup.594. PMID 15252823.

- ↑ Blanchard JC; Julou L. (March 1983). "Suriclone: a new cyclopyrrolone derivative recognizing receptors labeled by benzodiazepines in rat hippocampus and cerebellum". Journal of Neurochemistry. 40 (3): 601–607. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb08023.x. PMID 6298365.

- ↑ Skerritt, Jh; Johnston, Ga (May 1983). "Enhancement of GABA binding by benzodiazepines and related anxiolytics". European Journal of Pharmacology. 89 (3–4): 193–198. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(83)90494-6. ISSN 0014-2999. PMID 6135616.

- ↑ De, Deyn, Pp; Macdonald, Rl (September 1988). "Effects of non-sedative anxiolytic drugs on responses to GABA and on diazepam-induced enhancement of these responses on mouse neurones in cell culture". British Journal of Pharmacology. 95 (1): 109–120. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1988.tb16554.x. ISSN 0007-1188. PMC 1854132. PMID 2905900.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Julou L; Bardone MC; Blanchard JC; Garret C; Stutzmann JM. (1983). "Pharmacological studies on zopiclone". Pharmacology. 27 (2): 46–58. doi:10.1159/000137911. PMID 6142468.

- ↑ Blanchard JC; Boireau A; Julou L. (1983). "Brain receptors and zopiclone". Pharmacology. 27 (2): 59–69. doi:10.1159/000137912. PMID 6322210.

- ↑ Noguchi H; Kitazumi K; Mori M; Shiba T. (March 2004). "Electroencephalographic properties of zaleplon, a non-benzodiazepine sedative/hypnotic, in rats" (PDF). Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 94 (3): 246–251. doi:10.1254/jphs.94.246. PMID 15037809. Archived from the original on 2008-12-11. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ↑ Gaillot, J.; Heusse, D.; Houghton, G.W; Marc, Aurele, J.; Dreyfus, J.F. (1982). "Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of zopiclone". International Pharmacopsychiatry. 17 Suppl 2: 76–91. ISSN 0020-8272. PMID 7188377.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Viron, B; De Meyer, M; Le Liboux, A; Frydman, A; Maillard, F; Mignon, F; Gaillot, J (April 1990). "Steady State Pharmacokinetics of Zopiclone During Multiple Oral Dosing (7.5 mg nocte) in Patients with Severe Chronic Renal Failure". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 5 Suppl 2: 95–104. PMID 2387982.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 "Zopiclone". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ↑ Kratzsch C, Tenberken O, Peters FT et al. Screening, library-assisted identification, and validated quantification of 23 benzodiazepines, flumazenil, zaleplone, zolpidem, and zopiclone in plasma by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization. J. Mass Spec. 39: 856-872, 2004.

- ↑ Gustavsen I, Al-Sammurraie M, Mørland J, Bramness JG. Impairment related to blood drug concentrations of zopiclone and zolpidem compared with alcohol in apprehended drivers. Accid. Anal. Prev. 41: 462-466, 2009.

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1677-1679.

- ↑ Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D (January 2000). "Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia". CMAJ. 162 (2): 225–233. PMC 1232276. PMID 10674059.

- ↑ Blaschke, G; Hempel, G; Müller, We (1993). "Preparative and analytical separation of the zopiclone enantiomers and determination of their affinity to the benzodiazepine receptor binding site". Chirality. 5 (6): 419–421. doi:10.1002/chir.530050605. ISSN 0899-0042. PMID 8398600.

- ↑ Fernandez, C; Maradeix, V; Gimenez, F; Thuillier, A; Farinotti, R (November 1993). "Pharmacokinetics of zopiclone and its enantiomers in Caucasian young healthy volunteers". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 21 (6): 1125–1128. ISSN 0090-9556. PMID 7905394.

- ↑ Cimolai N (December 2007). "Zopiclone: is it a pharmacologic agent for abuse?". Can Fam Physician. 53 (12): 2124–2129. PMC 2231551. PMID 18077750.

- ↑ Griffiths RR, Johnson MW (2005). "Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 Suppl 9: 31–41. PMID 16336040.

- ↑ Hoffmann F, Pfannkuche M, Glaeske G (January 2008). "[High usage of zolpidem and zopiclone. Cross-sectional study using claims data]". Nervenarzt (in German). 79 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1007/s00115-007-2280-6. PMID 17457554. S2CID 31103719.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Bramness JG, Olsen H (May 1998). "[Adverse effects of zopiclone]". Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening (in Norwegian). 118 (13): 2029–2032. PMID 9656789.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Ströhle A, Antonijevic IA, Steiger A, Sonntag A (January 1999). "[Dependency of non-benzodiazepine hypnotics. Two case reports]". Nervenarzt (in German). 70 (1): 72–75. doi:10.1007/s001150050403. PMID 10087521. S2CID 42630879.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Sikdar S (July 1998). "Physical dependence on zopiclone. Prescribing this drug to addicts may give rise to iatrogenic drug misuse". BMJ. 317 (7151): 146. doi:10.1136/bmj.317.7151.146. PMC 1113504. PMID 9657802.

- ↑ Kuntze MF, Bullinger AH, Mueller-Spahn F (September 2002). "Excessive use of zopiclone: a case report" (PDF). Swiss Med Wkly. 132 (35–36): 523. PMID 12506335. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2008-12-18.

- ↑ Jones AW; Holmgren A; Kugelberg FC. (April 2007). "Concentrations of scheduled prescription drugs in blood of impaired drivers: considerations for interpreting the results". Therapeutic Drug Monitoring. 29 (2): 248–260. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e31803d3c04. PMID 17417081. S2CID 25511804. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2020-01-10.

- ↑ Bramness JG, Skurtveit S, Mørland J (August 1999). "[Detection of zopiclone in many drivers—a sign of misuse or abuse]". Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening (in Norwegian). 119 (19): 2820–2821. PMID 10494203.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Menzin J, Lang KM, Levy P, Levy E (January 2001). "A general model of the effects of sleep medications on the risk and cost of motor vehicle accidents and its application to France". PharmacoEconomics. 19 (1): 69–78. doi:10.2165/00019053-200119010-00005. PMID 11252547. S2CID 45013069.

- ↑ Kintz P, Villain M, Ludes B (April 2004). "Testing for the undetectable in drug-facilitated sexual assault using hair analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry as evidence". Ther Drug Monit. 26 (2): 211–214. doi:10.1097/00007691-200404000-00022. PMID 15228167. S2CID 46445345. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2020-01-10.

- ↑ Yanagita T. (1982). "Dependence potential of zopiclone studied in monkeys". International Pharmacopsychiatry. 17 (2): 216–227. PMID 6892368.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- CS1 errors: missing pipe

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- CS1: long volume value

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from February 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with permanently dead external links

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2020

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Carbamates

- Cyclopyrrolones

- Lactams

- Nonbenzodiazepines

- Chloropyridines

- Piperazines

- Pyrrolopyrazines

- Sanofi

- GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators

- RTT