Medroxyprogesterone

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɛˌdrɒksiproʊˈdʒɛstəroʊn ˈæsɪteɪt/ me-DROKS-ee-proh-JES-tər-ohn ASS-i-tayt[1] |

| Trade names | Provera, Depo-Provera, Depo-SubQ Provera 104, Curretab, Cycrin, Farlutal, Gestapuran, Perlutex, Veramix, others[2] |

| Other names | MPA; DMPA; methylhydroxy |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Progestogen; progestin; antigonadotropin; steroidal antiandrogen |

| Main uses | Birth control[3] |

| Side effects | Menstrual disturbances, abdominal pain, headaches[4] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, sublingual, intramuscular injection, subcutaneous injection |

| Duration of action | 3 months (depo injection)[3] |

| Defined daily dose | 1.67 gram[5] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604039 |

| Legal | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | By mouth: ~100%[6][7] |

| Protein binding | 88% (to albumin)[7] |

| Metabolism | Liver (hydroxylation (CYP3A4), reduction, conjugation)[8][6][9] |

| Elimination half-life | By mouth: 12–33 hours[8][6] IM (aq. susp.): ~50 days[10] SC (aq. susp.): ~40 days[11] |

| Excretion | Urine (as conjugates)[8] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C24H34O4 |

| Molar mass | 386.532 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 207 to 209 °C (405 to 408 °F) |

| |

| |

Medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), also known as depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in injectable form and sold under the brand name Depo-Provera among others, is a hormonal medication of the progestin type.[4][6] It is used as a method of birth control and as a part of menopausal hormone therapy.[4][6] It is also used to treat endometriosis, abnormal uterine bleeding, abnormal sexuality in males, and certain types of cancer.[4] The medication is available both alone and in combination with an estrogen.[12][13] It is taken by mouth, used under the tongue, or by injection into a muscle or fat.[4]

Common side effects include menstrual disturbances such as absence of periods, abdominal pain, and headaches.[4] More serious side effects include bone loss, blood clots, allergic reactions, and liver problems.[4] Use is not recommended during pregnancy as it may harm the baby.[4] MPA is an artificial progestogen, and as such activates the progesterone receptor, the biological target of progesterone.[6] It also has weak glucocorticoid activity and very weak androgenic activity but no other important hormonal activity.[6][14] Due to its progestogenic activity, MPA decreases the body's release of gonadotropins and can suppress sex hormone levels.[15] It works as a form of birth control by preventing ovulation.[4]

MPA was discovered in 1956 and was introduced for medical use in the United States in 1959.[16][17][4] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[18] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.60–1.60 per vial.[19] In the United Kingdom this dose costs the NHS about £6.[20] In the United States it costs less than $25 a dose as of 2015.[21] MPA is the most widely used progestin in menopausal hormone therapy and in progestogen-only birth control.[22][23] DMPA is approved for use as a form of long-acting birth control in more than 100 countries.[24][25] In 2017, it was the 222nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[26][27]

Medical uses

The most common use of MPA is in the form of DMPA as a long-acting progestogen-only injectable contraceptive to prevent pregnancy in women. It is an extremely effective contraceptive when used with relatively high doses to prevent ovulation. MPA is also used in combination with an estrogen in menopausal hormone therapy in postmenopausal women to treat and prevent menopausal symptoms such as hot flashes, vaginal atrophy, and osteoporosis.[6] It is used in menopausal hormone therapy specifically to prevent endometrial hyperplasia and cancer that would otherwise be induced by prolonged unopposed estrogen therapy in women with intact uteruses.[6][28] In addition to contraception and menopausal hormone therapy, MPA is used in the treatment of gynecological and menstrual disorders such as dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea, and endometriosis.[29] Along with other progestins, MPA was developed to allow for oral progestogen therapy, as progesterone (the progestogen hormone made by the human body) could not be taken orally for many decades before the process of micronization was developed and became feasible in terms of pharmaceutical manufacturing.[30]

DMPA reduces sex drive in men and is used as a form of chemical castration to control inappropriate or unwanted sexual behavior in those with paraphilias or hypersexuality, including in convicted sex offenders.[31][32] DMPA has also been used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia, as a palliative appetite stimulant for cancer patients, and at high doses (800 mg per day) to treat certain hormone-dependent cancers including endometrial cancer, renal cancer, and breast cancer.[33][34][35][36][37] MPA has also been prescribed in feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women due to its progestogenic and functional antiandrogenic effects.[38] It has been used to delay puberty in children with precocious puberty but is not satisfactory for this purpose as it is not able to completely suppress puberty.[39] DMPA at high doses has been reported to be definitively effective in the treatment of hirsutism as well.[40]

Though not used as a treatment for epilepsy, MPA has been found to reduce the frequency of seizures and does not interact with antiepileptic medications. MPA does not interfere with blood clotting and appears to improve blood parameters for women with sickle cell anemia. Similarly, MPA does not appear to affect liver metabolism, and may improve primary biliary cirrhosis and chronic active hepatitis. Women taking MPA may experience spotting shortly after starting the medication but is not usually serious enough to require medical intervention. With longer use amenorrhea (absence of menstruation) can occur as can irregular menstruation which is a major source of dissatisfaction, though both can result in improvements with iron deficiency and risk of pelvic inflammatory disease and often do not result in discontinuation of the medication.[34]

Birth control

| Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background | |

| Trade names | Depo-Provera, Depo-SubQ Provera 104, others |

| Type | Hormonal |

| First use | 1969[41] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | depo-provera |

| Failure rates (first year) | |

| Perfect use | 0.2%[42] |

| Typical use | 6%[42] |

| Usage | |

| Duration effect | 3 months (12–14 weeks) |

| Reversibility | 3–18 months |

| User reminders | Maximum interval is just under 3 months |

| Clinic review | 12 weeks |

| Advantages and disadvantages | |

| STI protection | No |

| Period disadvantages | Especially in first injection may be frequent spotting |

| Period advantages | Usually no periods from 2nd injection |

| Benefits | Especially good if poor pill compliance. Reduced endometrial cancer risk. |

| Risks | Reduced bone density, which may reverse after discontinuation |

| Medical notes | |

| For those intending to start family, suggest switch 6 months prior to alternative method (e.g. POP) allowing more reliable return fertility. | |

DMPA, under brand names such as Depo-Provera and Depo-SubQ Provera 104, is used in hormonal birth control as a long-lasting progestogen-only injectable contraceptive to prevent pregnancy in women.[43][44] It is given by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection and forms a long-lasting depot, from which it is slowly released over a period of several months. It takes one week to take effect if given after the first five days of the period cycle, and is effective immediately if given during the first five days of the period cycle. Estimates of first-year failure rates are about 0.3%.[45] MPA is effective in preventing pregnancy, but offers no protection against sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Effectiveness

Trussell's estimated perfect use first-year failure rate for DMPA as the average of failure rates in seven clinical trials at 0.3%.[45][46] It was considered perfect use because the clinical trials measured efficacy during actual use of DMPA defined as being no longer than 14 or 15 weeks after an injection (i.e., no more than 1 or 2 weeks late for a next injection).

Prior to 2004, Trussell's typical use failure rate for DMPA was the same as his perfect use failure rate: 0.3%.[47]

- DMPA estimated typical use first-year failure rate = 0.3% in:

In 2004, using the 1995 NSFG failure rate, Trussell increased (by 10 times) his typical use failure rate for DMPA from 0.3% to 3%.[45][46]

- DMPA estimated typical use first-year failure rate = 3% in:

Trussell did not use 1995 NSFG failure rates as typical use failure rates for the other two then newly available long-acting contraceptives, the Norplant implant (2.3%) and the ParaGard copper T 380A IUD (3.7%), which were (as with DMPA) an order of magnitude higher than in clinical trials. Since Norplant and ParaGard allow no scope for user error, their much higher 1995 NSFG failure rates were attributed by Trussell to contraceptive overreporting at the time of a conception leading to a live birth.[45][52][46]

Advantages

DMPA has a number of advantages and benefits:[53][54][44][55]

- Highly effective at preventing pregnancy.

- Injected every 12 weeks. The only continuing action is to book subsequent follow-up injections every twelve weeks, and to monitor side effects to ensure that they do not require medical attention.

- No estrogen. No increased risk of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke, or myocardial infarction.

- Minimal drug interactions (compared to other hormonal contraceptives).

- Decreased risk of endometrial cancer. DMPA reduces the risk of endometrial cancer by 80%.[56][57][58] The reduced risk of endometrial cancer in DMPA users is thought to be due to both the direct anti-proliferative effect of progestogen on the endometrium and the indirect reduction of estrogen levels by suppression of ovarian follicular development.[59]

- Decreased risk of iron deficiency anemia, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), ectopic pregnancy,[60][61] and uterine fibroids.

- Decreased symptoms of endometriosis.

- Decreased incidence of primary dysmenorrhea, ovulation pain, and functional ovarian cysts.

- Decreased incidence of seizures in women with epilepsy. Additionally, unlike most other hormonal contraceptives, DMPA's contraceptive effectiveness is not affected by enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs.[62]

- Decreased incidence and severity of sickle cell crises in women with sickle-cell disease.[44]

The United Kingdom Department of Health has actively promoted Long Acting Reversible Contraceptive use since 2008, particularly for young people;[63] following on from the October 2005 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines.[64] Giving advice on these methods of contraception has been included in the 2009 Quality and Outcomes Framework "good practice" for primary care.[65]

Comparison

Proponents of bioidentical hormone therapy believe that progesterone offers fewer side effects and improved quality of life compared to MPA.[66] The evidence for this view has been questioned; MPA is better absorbed when taken by mouth, with a much longer elimination half-life leading to more stable blood levels[67] though it may lead to greater breast tenderness and more sporadic vaginal bleeding.[66] The two compounds do not differentiate in their ability to suppress endometrial hyperplasia,[66] nor does either increase the risk of pulmonary embolism.[68] The two medications have not been adequately compared in direct tests to clear conclusions about safety and superiority.[30]

Available forms

MPA is available alone in the form of 2.5, 5, and 10 mg oral tablets, as a 150 mg/mL (1 mL) or 400 mg/mL (2.5 mL) microcrystalline aqueous suspension for intramuscular injection, and as a 104 mg (0.65 mL of 160 mg/mL) microcrystalline aqueous suspension for subcutaneous injection.[69][70] It has also been marketed in the form of 100, 200, 250, 400, and 500 mg oral tablets; 500 and 1,000 mg oral suspensions; and as a 50 mg/mL microcrystalline aqueous suspension for intramuscular injection.[71][72] A 100 mg/mL microcrystalline aqueous suspension for intramuscular injection was previously available as well.[69] In addition to single-drug formulations, MPA is available in the form of oral tablets in combination with conjugated estrogens (CEEs), estradiol, and estradiol valerate for use in menopausal hormone therapy, and is available in combination with estradiol cypionate in a microcrystalline aqueous suspension as a combined injectable contraceptive.[12][13][69][24]

Depo-Provera is the brand name for a 150 mg microcrystalline aqueous suspension of DMPA that is administered by intramuscular injection. The shot must be injected into thigh, buttock, or deltoid muscle four times a year (every 11 to 13 weeks), and provides pregnancy protection instantaneously after the first injection.[73] Depo-subQ Provera 104 is a variation of the original intramuscular DMPA that is instead a 104 mg microcrystalline dose in aqueous suspension administered by subcutaneous injection. It contains 69% of the MPA found in the original intramuscular DMPA formulation. It can be injected using a smaller injection needle inserting the medication just below the skin, instead of into the muscle, in either the abdomen or thigh. This subcutaneous injection claims to reduce the side effects of DMPA while still maintaining all the same benefits of the original intramuscular DMPA.

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 1.67 milligrams via injection.[5] This is generally given as 150 mg every 13 weeks or three months when used for birth control.[3]

Contraindications

MPA is not usually recommended because of unacceptable health risk or because it is not indicated in the following cases:[74][75]

Conditions where the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using DMPA:

- Multiple risk factors for arterial cardiovascular disease

- Current deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolus

- Migraine headache with aura while using DMPA

- Before evaluation of unexplained vaginal bleeding suspected of being a serious condition

- A history of breast cancer and no evidence of current disease for five years

- Active liver disease: (acute viral hepatitis, severe decompensated cirrhosis, benign or malignant liver tumours)

- Conditions of concern for estrogen deficiency and reduced HDL levels theoretically increasing cardiovascular risk:

- Hypertension with vascular disease

- Current and history of ischemic heart disease

- History of stroke

- Diabetes for over 20 years or with nephropathy/retinopathy/neuropathy or vascular disease

Conditions which represent an unacceptable health risk if DMPA is used:

- Current or recent breast cancer (a hormonally sensitive tumour)

Conditions where use is not indicated and should not be initiated:

MPA is not recommended for use prior to menarche or before or during recovery from surgery.[76]

Side effects

In women, the most common adverse effects of MPA are acne, changes in menstrual flow, drowsiness, and can cause birth defects if taken by pregnant women. Other common side effects include breast tenderness, increased facial hair, decreased scalp hair, difficulty falling or remaining asleep, stomach pain, and weight loss or gain.[29] Lowered libido has been reported as a side effect of MPA in women.[77] DMPA can affect menstrual bleeding. After a year of use, 55% of women experience amenorrhea (missed periods); after 2 years, the rate rises to 68%. In the first months of use "irregular or unpredictable bleeding or spotting, or, rarely, heavy or continuous bleeding" was reported.[78] MPA does not appear to be associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.[79] Data on weight gain with DMPA likewise are inconsistent.[80][81]

At high doses for the treatment of breast cancer, MPA can cause weight gain and can worsen diabetes mellitus and edema (particularly of the face). Adverse effects peak at five weeks, and are reduced with lower doses. Less frequent effects may include thrombosis (though it is not clear if this is truly a risk, it cannot be ruled out), painful urination, headache, nausea, and vomiting. When used as a form of androgen deprivation therapy in men, more frequent complaints include reduced libido, impotence, reduced ejaculate volume, and within three days, chemical castration. At extremely high doses (used to treat cancer, not for contraception) MPA may cause adrenal suppression and may interfere with carbohydrate metabolism, but does not cause diabetes.[34]

When used as a form of injected birth control, there is a delayed return of fertility. The average return to fertility is 9 to 10 months after the last injection, taking longer for overweight or obese women. By 18 months after the last injection, fertility is the same as that in former users of other contraceptive methods.[53][54] Fetuses exposed to progestogens have demonstrated higher rates of genital abnormalities, low birth weight, and increased ectopic pregnancy particularly when MPA is used as an injected form of long-term birth control. A study of accidental pregnancies among poor women in Thailand found that infants who had been exposed to DMPA during pregnancy had a higher risk of low birth weight and an 80% greater-than-usual chance of dying in the first year of life.[82]

Mood changes

There have been concerns about a possible risk of depression and mood changes with progestins like MPA, and this has led to reluctance of some clinicians and women to use them.[83][84] However, contrary to widely-held beliefs, most research suggests that progestins do not cause adverse psychological effects such as depression or anxiety.[83] A 2018 systematic review of the relationship between progestin-based contraception and depression included three large studies of DMPA and reported no association between DMPA and depression.[85] According to a 2003 review of DMPA, the majority of published clinical studies indicate that DMPA is not associated with depression, and the overall data support the notion that the medication does not significantly affect mood.[86]

In the largest study to have assessed the relationship between MPA and depression to date, in which over 3,900 women were treated with DMPA for up to 7 years, the incidence of depression was infrequent at 1.5% and the discontinuation rate due to depression was 0.5%.[85][43][87] This study did not include baseline data on depression,[87] and due to the incidence of depression in the study, the FDA required package labeling for DMPA stating that women with depression should be observed carefully and that DMPA should be discontinued if depression recurs.[85] A subsequent study of 495 women treated with DMPA over the course of 1 year found that the mean depression score slightly decreased in the whole group of continuing users from 7.4 to 6.7 (by 9.5%) and decreased in the quintile of that group with the highest depression scores at baseline from 15.4 to 9.5 (by 38%).[87] Based on the results of this study and others, a consensus began emerging that DMPA does not in fact increase the risk of depression nor worsen the severity of pre-existing depression.[81][87][43]

Similarly to the case of DMPA for hormonal contraception, the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS), a study of 2,763 postmenopausal women treated with 0.625 mg/day oral CEEs plus 2.5 mg/day oral MPA or placebo for 36 months as a method of menopausal hormone therapy, found no change in depressive symptoms.[88][89][90] However, some small studies have reported that progestins like MPA might counteract beneficial effects of estrogens against depression.[83][6][91]

Long-term effects

The Women's Health Initiative investigated the use of a combination of oral CEEs and MPA compared to placebo. The study was prematurely terminated when previously unexpected risks were discovered, specifically the finding that though the all-cause mortality was not affected by the hormone therapy, the benefits of menopausal hormone therapy (reduced risk of hip fracture, colorectal and endometrial cancer and all other causes of death) were offset by increased risk of coronary heart disease, breast cancer, strokes and pulmonary embolism.[92] However, the study focused on MPA only and extrapolated the benefits versus risks to all progestogens – a conclusion that has been challenged by several researchers as unjustified and leading to unnecessary avoidance of HRT for many women as progestogens are not alike.[93]

When combined with CEEs, MPA has been associated with an increased risk of breast cancer, dementia, and thrombus in the eye. In combination with estrogens in general, MPA may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, with a stronger association when used by postmenopausal women also taking CEEs. It was because of these unexpected interactions that the Women's Health Initiative study was ended early due the extra risks of menopausal hormone therapy,[94] resulting in a dramatic decrease in both new and renewal prescriptions for hormone therapy.[95]

Long-term studies of users of DMPA have found slight or no increased overall risk of breast cancer. However, the study population did show a slightly increased risk of breast cancer in recent users (DMPA use in the last four years) under age 35, similar to that seen with the use of combined oral contraceptive pills.[78]

| Clinical outcome | Hypothesized effect on risk |

Estrogen and progestogen (CEs 0.625 mg/day p.o. + MPA 2.5 mg/day p.o.) (n = 16,608, with uterus, 5.2–5.6 years follow up) |

Estrogen alone (CEs 0.625 mg/day p.o.) (n = 10,739, no uterus, 6.8–7.1 years follow up) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | AR | HR | 95% CI | AR | ||

| Coronary heart disease | Decreased | 1.24 | 1.00–1.54 | +6 / 10,000 PYs | 0.95 | 0.79–1.15 | −3 / 10,000 PYs |

| Stroke | Decreased | 1.31 | 1.02–1.68 | +8 / 10,000 PYs | 1.37 | 1.09–1.73 | +12 / 10,000 PYs |

| Pulmonary embolism | Increased | 2.13 | 1.45–3.11 | +10 / 10,000 PYs | 1.37 | 0.90–2.07 | +4 / 10,000 PYs |

| Venous thromboembolism | Increased | 2.06 | 1.57–2.70 | +18 / 10,000 PYs | 1.32 | 0.99–1.75 | +8 / 10,000 PYs |

| Breast cancer | Increased | 1.24 | 1.02–1.50 | +8 / 10,000 PYs | 0.80 | 0.62–1.04 | −6 / 10,000 PYs |

| Colorectal cancer | Decreased | 0.56 | 0.38–0.81 | −7 / 10,000 PYs | 1.08 | 0.75–1.55 | +1 / 10,000 PYs |

| Endometrial cancer | – | 0.81 | 0.48–1.36 | −1 / 10,000 PYs | – | – | – |

| Hip fractures | Decreased | 0.67 | 0.47–0.96 | −5 / 10,000 PYs | 0.65 | 0.45–0.94 | −7 / 10,000 PYs |

| Total fractures | Decreased | 0.76 | 0.69–0.83 | −47 / 10,000 PYs | 0.71 | 0.64–0.80 | −53 / 10,000 PYs |

| Total mortality | Decreased | 0.98 | 0.82–1.18 | −1 / 10,000 PYs | 1.04 | 0.91–1.12 | +3 / 10,000 PYs |

| Global index | – | 1.15 | 1.03–1.28 | +19 / 10,000 PYs | 1.01 | 1.09–1.12 | +2 / 10,000 PYs |

| Diabetes | – | 0.79 | 0.67–0.93 | 0.88 | 0.77–1.01 | ||

| Gallbladder disease | Increased | 1.59 | 1.28–1.97 | 1.67 | 1.35–2.06 | ||

| Stress incontinence | – | 1.87 | 1.61–2.18 | 2.15 | 1.77–2.82 | ||

| Urge incontinence | – | 1.15 | 0.99–1.34 | 1.32 | 1.10–1.58 | ||

| Peripheral artery disease | – | 0.89 | 0.63–1.25 | 1.32 | 0.99–1.77 | ||

| Probable dementia | Decreased | 2.05 | 1.21–3.48 | 1.49 | 0.83–2.66 | ||

| Abbreviations: CEs = conjugated estrogens. MPA = medroxyprogesterone acetate. p.o. = per oral. HR = hazard ratio. AR = attributable risk. PYs = person–years. CI = confidence interval. Notes: Sample sizes (n) include placebo recipients, which were about half of patients. "Global index" is defined for each woman as the time to earliest diagnosis for coronary heart disease, stroke, pulmonary embolism, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer (estrogen plus progestogen group only), hip fractures, and death from other causes. Sources: See template. | |||||||

Blood clots

DMPA has been associated in multiple studies with a higher risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) when used as a form of progestogen-only birth control in premenopausal women.[96][97][98][99] The increase in incidence of VTE ranges from 2.2-fold to 3.6-fold.[96][97][98][99] Elevated risk of VTE with DMPA is unexpected, as DMPA has little or no effect on coagulation and fibrinolytic factors,[100][101] and progestogens by themselves normally do not increase the risk of thrombosis.[97][98] It has been argued that the higher incidence with DMPA has reflected preferential prescription of DMPA to women considered to be at an increased risk of VTE.[97] Alternatively, it is possible that MPA may be an exception among progestins in terms of VTE risk.[102][103][104] A 2018 meta-analysis reported that MPA was associated with a 2.8-fold higher risk of VTE than other progestins.[103] It is possible that the glucocorticoid activity of MPA may increase the risk of VTE.[6][105][104]

Bone density

DMPA may cause reduced bone density in premenopausal women and in men when used without an estrogen, particularly at high doses, though this appears to be reversible to a normal level even after years of use.

On November 17, 2004, the United States Food and Drug Administration put a black box warning on the label, indicating that there were potential adverse effects of loss of bone mineral density.[106][107] While it causes temporary bone loss, most women fully regain their bone density after discontinuing use.[80] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that the use not be restricted.[108][109] The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists notes that the potential adverse effects on BMD be balanced against the known negative effects of unintended pregnancy using other birth control methods or no method, particularly among adolescents.

Three studies have suggested that bone loss is reversible after the discontinuation of DMPA.[110][111][112] Other studies have suggested that the effect of DMPA use on postmenopausal bone density is minimal,[113] perhaps because DMPA users experience less bone loss at menopause.[114] Use after peak bone mass is associated with increased bone turnover but no decrease in bone mineral density.[115]

The FDA recommends that DMPA not be used for longer than 2 years, unless there is no viable alternative method of contraception, due to concerns over bone loss.[107] However, a 2008 Committee Opinion from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises healthcare providers that concerns about bone mineral density loss should neither prevent the prescription of or continuation of DMPA beyond 2 years of use.[116]

HIV risk

There is uncertainty regarding the risk of HIV acquisition among DMPA users; some observational studies suggest an increased risk of HIV acquisition among women using DMPA, while others do not.[117] The World Health Organization issued statements in February 2012 and July 2014 saying the data did not warrant changing their recommendation of no restriction – Medical Eligibility for Contraception (MEC) category 1 – on the use of DMPA in women at high risk for HIV.[118][119] Two meta-analyses of observational studies in sub-Saharan Africa were published in January 2015.[120] They found a 1.4- to 1.5-fold increase risk of HIV acquisition for DMPA users relative to no hormonal contraceptive use.[121][122] In January 2015, the Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists issued a statement reaffirming that there is no reason to advise against use of DMPA in the United Kingdom even for women at 'high risk' of HIV infection.[123] A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk of HIV infection in DMPA users published in fall of 2015 stated that "the epidemiological and biological evidence now make a compelling case that DMPA adds significantly to the risk of male-to-female HIV transmission."[124] In 2019, a randomized controlled trial found no significant association between DMPA use and HIV.[125]

Breastfeeding

MPA may be used by breastfeeding mothers. Heavy bleeding is possible if given in the immediate postpartum time and is best delayed until six weeks after birth. It may be used within five days if not breast feeding. While a study showed "no significant difference in birth weights or incidence of birth defects" and "no significant alternation of immunity to infectious disease caused by breast milk containing DMPA", a subgroup of babies whose mothers started DMPA at 2 days postpartum had a 75% higher incidence of doctor visits for infectious diseases during their first year of life.[126]

A larger study with longer follow-up concluded that "use of DMPA during pregnancy or breastfeeding does not adversely affect the long-term growth and development of children". This study also noted that "children with DMPA exposure during pregnancy and lactation had an increased risk of suboptimal growth in height," but that "after adjustment for socioeconomic factors by multiple logistic regression, there was no increased risk of impaired growth among the DMPA-exposed children." The study also noted that effects of DMPA exposure on puberty require further study, as so few children over the age of 10 were observed.[127]

Overdose

MPA has been studied at "massive" dosages of up to 5,000 mg per day orally and 2,000 mg per day via intramuscular injection, without major tolerability or safety issues described.[128][129][130] Overdose is not described in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) product labels for injected MPA (Depo-Provera or Depo-SubQ Provera 104).[10][11] In the FDA product label for oral MPA (Provera), it is stated that overdose of an estrogen and progestin may cause nausea and vomiting, breast tenderness, dizziness, abdominal pain, drowsiness, fatigue, and withdrawal bleeding.[8] According to the label, treatment of overdose should consist of discontinuation of MPA therapy and symptomatic care.[8]

Interactions

MPA increases the risk of breast cancer, dementia, and thrombus when used in combination with CEEs to treat menopausal symptoms.[76] When used as a contraceptive, MPA does not generally interact with other medications. The combination of MPA with aminoglutethimide to treat metastases from breast cancer has been associated with an increase in depression.[34] St John's wort may decrease the effectiveness of MPA as a contraceptive due to acceleration of its metabolism.[76]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

MPA acts as an agonist of the progesterone, androgen, and glucocorticoid receptors (PR, AR, and GR, respectively),[7] activating these receptors with EC50 values of approximately 0.01 nM, 1 nM, and 10 nM, respectively.[131] It has negligible affinity for the estrogen receptor.[7] The medication has relatively high affinity for the mineralocorticoid receptor, but in spite of this, it has no mineralocorticoid or antimineralocorticoid activity.[6] The intrinsic activities of MPA in activating the PR and the AR have been reported to be at least equivalent to those of progesterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT), respectively, indicating that it is a full agonist of these receptors.[14][132]

| PR | AR | ER | GR | MR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | 50 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 100 |

| Chlormadinone acetate | 67 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Cyproterone acetate | 90 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 8 |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 115 | 5 | 0 | 29 | 160 |

| Megestrol acetate | 65 | 5 | 0 | 30 | 0 |

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were promegestone for the PR, metribolone for the AR, estradiol for the ER, dexamethasone for the GR, and aldosterone for the MR. Sources: [6] | |||||

Progestogenic activity

MPA is a potent agonist of the progesterone receptor with similar affinity and efficacy relative to progesterone.[133] While both MPA and its deacetylated analogue medroxyprogesterone bind to and agonize the PR, MPA has approximately 100-fold higher binding affinity and transactivation potency in comparison.[133] As such, unlike MPA, medroxyprogesterone is not used clinically, though it has seen some use in veterinary medicine.[2] The oral dosage of MPA required to inhibit ovulation (i.e., the effective contraceptive dosage) is 10 mg/day, whereas 5 mg/day was not sufficient to inhibit ovulation in all women.[134] In accordance, the dosage of MPA used in oral contraceptives in the past was 10 mg per tablet.[135] For comparison to MPA, the dosage of progesterone required to inhibit ovulation is 300 mg/day, whereas that of the 19-nortestosterone derivatives norethisterone and norethisterone acetate is only 0.4 to 0.5 mg/day.[136]

The mechanism of action of progestogen-only contraceptives like DMPA depends on the progestogen activity and dose. High-dose progestogen-only contraceptives, such as DMPA, inhibit follicular development and prevent ovulation as their primary mechanism of action.[137][138] The progestogen decreases the pulse frequency of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) release by the hypothalamus, which decreases the release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) by the anterior pituitary. Decreased levels of FSH inhibit follicular development, preventing an increase in estradiol levels. Progestogen negative feedback and the lack of estrogen positive feedback on LH release prevent a LH surge. Inhibition of follicular development and the absence of a LH surge prevent ovulation.[53][54] A secondary mechanism of action of all progestogen-containing contraceptives is inhibition of sperm penetration by changes in the cervical mucus.[139] Inhibition of ovarian function during DMPA use causes the endometrium to become thin and atrophic. These changes in the endometrium could, theoretically, prevent implantation. However, because DMPA is highly effective in inhibiting ovulation and sperm penetration, the possibility of fertilization is negligible. No available data support prevention of implantation as a mechanism of action of DMPA.[139]

| Compound | Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM)a | EC50 (nM)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | 4.3 | 0.9 | 25 |

| Medroxyprogesterone | 241 | 47 | 32 |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.15 |

| Footnotes: a = Coactivator recruitment. b = Reporter cell line. Sources: [133] | |||

| Progestogen | OID (mg/day) |

TFD (mg/cycle) |

TFD (mg/day) |

ODP (mg/day) |

ECD (mg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone | 300 | 4200 | 200–300 | – | 200 |

| Chlormadinone acetate | 1.7 | 20–30 | 10 | 2.0 | 5–10 |

| Cyproterone acetate | 1.0 | 20 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | 10 | 50 | 5–10 | ? | 5.0 |

| Megestrol acetate | ? | 50 | ? | ? | 5.0 |

| Abbreviations: OID = ovulation-inhibiting dosage (without additional estrogen). TFD = endometrial transformation dosage. ODP = oral dosage in commercial contraceptive preparations. ECD = estimated comparable dosage. Sources: [136][105][140] | |||||

| Progestogen | Form | Major brand names | Class | TFD (14 days) |

POIC-D (2–3 months) |

CIC-D (month) |

Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algestone acetophenide | Oil solution | Perlutal, Topasel, Yectames | Pregnane | ? | – | 75–150 mg | 100 mg ≈ 14–32 days | |

| Cyproterone acetate | Oil solution | Androcur Depot | Pregnane | ? | – | – | 300 mg ≈ 20 days | |

| Dydrogesteronea | Aqueous suspension | – | Retropregnane | ? | – | – | 100 mg ≈ 16–38 days | |

| Gestonorone caproate | Oil solution | Depostat, Primostat | Norpregnane | 25–50 mg | – | – | 25–50 mg ≈ 8–13 days | |

| Hydroxyprogesterone acetatea | Aqueous suspension | – | Pregnane | 350 mg | – | – | 150–350 mg ≈ 9–16 days | |

| Hydroxyprogesterone caproate | Oil solution | Delalutin, Proluton, Makena | Pregnane | 250–500 mgb | – | 250–500 mg | 65–500 mg ≈ 5–21 days | |

| Levonorgestrel butanoatea | Aqueous suspension | – | Gonane | ? | – | – | 5–50 mg ≈ 3–6 months | |

| Lynestrenol phenylpropionatea | Oil solution | – | Estrane | ? | – | – | 50–100 mg ≈ 14–30 days | |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | Aqueous suspension | Depo-Provera | Pregnane | 50–100 mg | 150 mg | 25 mg | 50–150 mg ≈ 14–50+ days | |

| Megestrol acetate | Aqueous suspension | Mego-E | Pregnane | ? | – | 25 mg | 25 mg ≈ >14 daysc | |

| Norethisterone enanthate | Oil solution | Noristerat, Mesigyna | Estrane | 100–200 mg | 200 mg | 50 mg | 50–200 mg ≈ 11–52 days | |

| Oxogestone phenylpropionatea | Oil solution | – | Norpregnane | ? | – | – | 100 mg ≈ 19–20 days | |

| Progesterone | Oil solution | Progestaject, Gestone, Strone | Pregnane | 200 mgb | – | – | 25–350 mg ≈ 2–6 days | |

| Aqueous suspension | Agolutin Depot | Pregnane | 50–200 mg | – | – | 50–300 mg ≈ 7–14 days | ||

| Note: All by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection. All are synthetic except for P4, which is bioidentical. P4 production during the luteal phase is ~25 (15–50) mg/day. The OID of OHPC is 250 to 500 mg/month. Footnotes: a = Never marketed by this route. b = In divided doses (2 × 125 or 250 mg for OHPC, 10 × 20 mg for P4). c = Half-life is ~14 days. Sources: Main: See template. | ||||||||

Antigonadotropic and anticorticotropic effects

MPA suppresses the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) and hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axes at sufficient dosages, resulting decreased levels of gonadotropins, androgens, estrogens, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and cortisol, as well as levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG).[15] There is evidence that the suppressive effects of MPA on the HPG axis are mediated by activation of both the PR and the AR in the pituitary gland.[141][142] Due to its effects on androgen levels, MPA can produce strong functional antiandrogenic effects, and is used in the treatment of androgen-dependent conditions such as precocious puberty in boys and hypersexuality in men.[143] In addition, since the medication suppresses estrogen levels as well, MPA can produce strong functional antiestrogenic effects similarly, and has been used to treat estrogen-dependent conditions such as precocious puberty in girls and endometriosis in women. Due to low estrogen levels, the use of MPA without an estrogen poses a risk of decreased bone mineral density and other symptoms of estrogen deficiency.[144]

Oral MPA has been found to suppress testosterone levels in men by about 30% (from 831 ng/dL to 585 ng/dL) at a dosage of 20 mg/day, by about 45 to 75% (average 60%; to 150–400 ng/dL) at a dosage of 60 mg/day,[145][146][147] and by about 70 to 75% (from 832–862 ng/dL to 214–251 ng/dL) at a dosage of 100 mg/day.[148][149] Dosages of oral MPA of 2.5 to 30 mg/day in combination with estrogens have been used to help suppress testosterone levels in transgender women.[150][151][152][153][154][155] Very high dosages of intramuscular MPA of 150 to 500 mg per week (but up to 900 mg per week) can suppress testosterone levels to less than 100 ng/dL.[145][156] The typical initial dose of intramuscular MPA for testosterone suppression in men with paraphilias is 400 or 500 mg per week.[145]

Androgenic activity

MPA is a potent full agonist of the AR. Its activation of the AR may play an important and major role in its antigonadotropic effects and in its beneficial effects against breast cancer.[141][157][158] However, although MPA may produce androgenic side effects such as acne and hirsutism in some women,[159][160] it rarely does so, and when such symptoms occur, they tend to be mild, regardless of the dosage used.[141] In fact, likely due to its suppressive actions on androgen levels, it has been reported that MPA is generally highly effective in improving pre-existing symptoms of hirsutism in women with the condition.[161][162] Moreover, MPA rarely causes any androgenic effects in children with precocious puberty, even at very high doses.[163] The reason for the general lack of virilizing effects with MPA, despite it binding to and activating the AR with high affinity and this action potentially playing an important role in many of its physiological and therapeutic effects, is not entirely clear. However, MPA has been found to interact with the AR differently compared to other agonists of the receptor such as dihydrotestosterone (DHT).[14] The result of this difference appears to be that MPA binds to the AR with a similar affinity and intrinsic activity to that of DHT, but requires about 100-fold higher concentrations for a comparable induction of gene transcription, while at the same time not antagonizing the transcriptional activity of normal androgens like DHT at any concentration.[14] Thus, this may explain the low propensity of MPA for producing androgenic side effects.[14]

MPA shows weak androgenic effects on liver protein synthesis, similarly to other weakly androgenic progestins like megestrol acetate and 19-nortestosterone derivatives.[6][9] While it does not antagonize estrogen-induced increases in levels of triglycerides and HDL cholesterol, DMPA every other week may decrease levels of HDL cholesterol.[6] In addition, MPA has been found to suppress sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) production by the liver.[9][164][165] At a dosage of 10 mg/day oral MPA, it has been found to decrease circulating SHBG levels by 14 to 18% in women taking 4 mg/day oral estradiol valerate.[9] Conversely, in a study that combined 2.5 mg/day oral MPA with various oral estrogens, no influence of MPA on estrogen-induced increases in SHBG levels was discerned.[165] In another, higher-dose study, SHBG levels were lower by 59% in a group of women treated with 50 mg/day oral MPA alone relative to an untreated control group of women.[164]

Unlike the related steroids megestrol acetate and cyproterone acetate, MPA is not an antagonist of the AR and does not have direct antiandrogenic activity.[6] As such, although MPA is sometimes described as an antiandrogen, it is not a "true" antiandrogen (i.e., AR antagonist).[146]

Glucocorticoid activity

As an agonist of the GR, MPA has glucocorticoid activity, and as a result can cause symptoms of Cushing's syndrome,[166] steroid diabetes, and adrenal insufficiency at sufficiently high doses.[167] It has been suggested that the glucocorticoid activity of MPA may contribute to bone loss.[168] The glucocorticoid activity of MPA may also result in an upregulation of the thrombin receptor in blood vessel walls, which may contribute to procoagulant effects of MPA and risk of venous thromboembolism and atherosclerosis.[6] The relative glucocorticoid activity of MPA is among the highest of the clinically used progestins.[6]

| Steroid | Class | TR (↑)a | GR (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone | Corticosteroid | ++ | 100 |

| Ethinylestradiol | Estrogen | – | 0 |

| Etonogestrel | Progestin | + | 14 |

| Gestodene | Progestin | + | 27 |

| Levonorgestrel | Progestin | – | 1 |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | Progestin | + | 29 |

| Norethisterone | Progestin | – | 0 |

| Norgestimate | Progestin | – | 1 |

| Progesterone | Progestogen | + | 10 |

| Footnotes: a = Thrombin receptor (TR) upregulation (↑) in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). b = RBA (%) for the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Strength: – = No effect. + = Pronounced effect. ++ = Strong effect. Sources: See template. | |||

Steroidogenesis inhibition

MPA has been found to act as a competitive inhibitor of rat 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD).[169][170][171][172] This enzyme is essential for the transformation of progesterone, deoxycorticosterone, and DHT into inhibitory neurosteroids such as allopregnanolone, THDOC, and 3α-androstanediol, respectively.[173] MPA has been described as very potent in its inhibition of rat 3α-HSD, with an IC50 of 0.2 μM and a Ki (in rat testicular homogenates) of 0.42 μM.[169][170] However, inhibition of 3α-HSD by MPA does not appear to have been confirmed using human proteins yet, and the concentrations required with rat proteins are far above typical human therapeutic concentrations.[169][170]

MPA has been identified as a competitive inhibitor of human 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/Δ5-4 isomerase II (3β-HSD II).[174] This enzyme is essential for the biosynthesis of sex steroids and corticosteroids.[174] The Ki of MPA for inhibition of 3β-HSD II is 3.0 μM, and this concentration is reportedly near the circulating levels of the medication that are achieved by very high therapeutic dosages of MPA of 5 to 20 mg/kg/day (dosages of 300 to 1,200 mg/day for a 60 kg (132 lb) person).[174] Aside from 3β-HSD II, other human steroidogenic enzymes, including cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc/CYP11A1) and 17α-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase (CYP17A1), were not found to be inhibited by MPA.[174] MPA has been found to be effective in the treatment of gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty and in breast cancer in postmenopausal women at high dosages, and inhibition of 3β-HSD II could be responsible for its effectiveness in these conditions.[174]

GABAA receptor allosteric modulation

Progesterone, via transformation into neurosteroids such as 5α-dihydroprogesterone, 5β-dihydroprogesterone, allopregnanolone, and pregnanolone (catalyzed by the enzymes 5α- and 5β-reductase and 3α- and 3β-HSD), is a positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor, and is associated with a variety of effects mediated by this property including dizziness, sedation, hypnotic states, mood changes, anxiolysis, and cognitive/memory impairment, as well as effectiveness as an anticonvulsant in the treatment of catamenial epilepsy.[173][175] It has also been found to produce anesthesia via this action in animals when administered at sufficiently high dosages.[175] MPA was found to significantly reduce seizure incidence when added to existing anticonvulsant regimens in 11 of 14 women with uncontrolled epilepsy, and has also been reported to induce anesthesia in animals, raising the possibility that it might modulate the GABAA receptor similarly to progesterone.[176][177]

MPA shares some of the same metabolic routes of progesterone and, analogously, can be transformed into metabolites such as 5α-dihydro-MPA (DHMPA) and 3α,5α-tetrahydro-MPA (THMPA).[176] However, unlike the reduced metabolites of progesterone, DHMPA and THMPA have been found not to modulate the GABAA receptor.[176] Conversely, unlike progesterone, MPA itself actually modulates the GABAA receptor, although notably not at the neurosteroid binding site.[176] However, rather than act as a potentiator of the receptor, MPA appears to act as a negative allosteric modulator.[176] Whereas the reduced metabolites of progesterone enhance binding of the benzodiazepine flunitrazepam to the GABAA receptor in vitro, MPA can partially inhibit the binding of flunitrazepam by up to 40% with half-maximal inhibition at 1 μM.[176] However, the concentrations of MPA required for inhibition are high relative to therapeutic concentrations, and hence, this action is probably of little or no clinical relevance.[176] The lack of potentiation of the GABAA receptor by MPA or its metabolites is surprising in consideration of the apparent anticonvulsant and anesthetic effects of MPA described above, and they remain unexplained.[176]

Clinical studies using massive dosages of up to 5,000 mg/day oral MPA and 2,000 mg/day intramuscular MPA for 30 days in women with advanced breast cancer have reported "no relevant side effects", which suggests that MPA has no meaningful direct action on the GABAA receptor in humans even at extremely high dosages.[128]

Appetite stimulation

Although MPA and the closely related medication megestrol acetate are effective appetite stimulants at very high dosages,[178] the mechanism of action of their beneficial effects on appetite is not entirely clear. However, glucocorticoid, cytokine, and possibly anabolic-related mechanisms are all thought to possibly be involved, and a number of downstream changes have been implicated, including stimulation of the release of neuropeptide Y in the hypothalamus, modulation of calcium channels in the ventromedial hypothalamus, and inhibition of the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, actions that have all been linked to an increase in appetite.[179]

Other activity

MPA weakly stimulates the proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells in vitro, an action that is independent of the classical PRs and is instead mediated via the progesterone receptor membrane component-1 (PGRMC1).[180] Certain other progestins are also active in this assay, whereas progesterone acts neutrally.[180] It is unclear if these findings may explain the different risks of breast cancer observed with progesterone, dydrogesterone, and other progestins such as medroxyprogesterone acetate and norethisterone in clinical studies.[181]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Surprisingly few studies have been conducted on the pharmacokinetics of MPA at postmenopausal replacement dosages.[182][6] The bioavailability of MPA with oral administration is approximately 100%.[6] A single oral dose of 10 mg MPA has been found to result in peak MPA levels of 1.2 to 5.2 ng/mL within 2 hours of administration using radioimmunoassay.[182][183] Following this, levels of MPA decreased to 0.09 to 0.35 ng/mL 12 hours post-administration.[182][183] In another study, peak levels of MPA were 3.4 to 4.4 ng/mL within 1 to 4 hours of administration of 10 mg oral MPA using radioimmunoassay.[182][184] Subsequently, MPA levels fell to 0.3 to 0.6 ng/mL 24 hours after administration.[182][184] In a third study, MPA levels were 4.2 to 4.4 ng/mL after an oral dose of 5 mg MPA and 6.0 ng/mL after an oral dose of 10 mg MPA, both using radioimmunoassay as well.[182][185]

Treatment of postmenopausal women with 2.5 or 5 mg/day MPA in combination with estradiol valerate for two weeks has been found to rapidly increase circulating MPA levels, with steady-state concentrations achieved after 3 days and peak concentrations occurring 1.5 to 2 hours after ingestion.[6][186] With 2.5 mg/day MPA, levels of the medication were 0.3 ng/mL (0.8 nmol/L) in women under 60 years of age and 0.45 ng/mL (1.2 nmol/L) in women 65 years of age or over, and with 5 mg/day MPA, levels were 0.6 ng/mL (1.6 nmol/L) in women under 60 years of age and in women 65 years of age or over.[6][186] Hence, area-under-curve levels of the medication were 1.6 to 1.8 times higher in those who were 65 years of age or older relative to those who were 60 years of age or younger.[9][186] As such, levels of MPA have been found to vary with age, and MPA may have an increased risk of side effects in elderly postmenopausal women.[9][6][186] This study assessed MPA levels using liquid-chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS), a more accurate method of blood determinations.[186]

Oral MPA tablets can be administered sublingually instead of orally.[187][188][189] Rectal administration of MPA has also been studied.[190]

With intramuscular administration of 150 mg microcrystalline MPA in aqueous suspension, the medication is detectable in the circulation within 30 minutes, serum concentrations vary but generally plateau at 1.0 ng/mL (2.6 nmol/L) for 3 months.[191] Following this, there is a gradual decline in MPA levels, and the medication can be detected in the circulation for as long as 6 to 9 months post-injection.[191] The particle size of MPA crystals significantly influences its rate of absorption into the body from the local tissue depot when used as a microcrystalline aqueous suspension via intramuscular injection.[192][193][194] Smaller crystals dissolve faster and are absorbed more rapidly, resulting in a shorter duration of action.[192][193][194] Particle sizes can differ between different formulations of MPA, potentially influencing clinical efficacy and tolerability.[192][193][194][195]

Distribution

The plasma protein binding of MPA is 88%.[6][9] It is weakly bound to albumin and is not bound to sex hormone-binding globulin or corticosteroid-binding globulin.[6][9]

Metabolism

The elimination half-life of MPA via oral administration has been reported as both 11.6 to 16.6 hours[8] and 33 hours,[6] whereas the elimination half-lives with intramuscular and subcutaneous injection of microcrystalline MPA in aqueous suspension are 50 and 40 days, respectively.[10][11] The metabolism of MPA is mainly via hydroxylation, including at positions C6β, C21, C2β, and C1β, mediated primarily via CYP3A4, but 3- and 5-dihydro and 3,5-tetrahydro metabolites of MPA are also formed.[6][9] Deacetylation of MPA and its metabolites (into, e.g., medroxyprogesterone) has been observed to occur in non-human primate research to a substantial extent as well (30 to 70%).[196] MPA and/or its metabolites are also metabolized via conjugation.[76] The C6α methyl and C17α acetoxy groups of MPA make it more resistant to metabolism and allow for greater bioavailability than oral progesterone.[9]

Elimination

MPA is eliminated 20 to 50% in urine and 5 to 10% in feces following intravenous administration.[197] Less than 3% of a dose is excreted in unconjugated form.[197]

Level–effect relationships

With intramuscular administration, the high levels of MPA in the blood inhibit luteinizing hormone and ovulation for several months, with an accompanying decrease in serum progesterone to below 0.4 ng/mL.[191] Ovulation resumes when once blood levels of MPA fall below 0.1 ng/mL.[191] Serum estradiol remains at approximately 50 pg/mL for approximately four months post-injection (with a range of 10–92 pg/mL after several years of use), rising once MPA levels fall below 0.5 ng/mL.[191]

Hot flashes are rare while MPA is found at significant blood levels in the body, and the vaginal lining remains moist and creased. The endometrium undergoes atrophy, with small, straight glands and a stroma that is decidualized. Cervical mucus remains viscous. Because of its steady blood levels over the long term and multiple effects that prevent fertilization, MPA is a very effective means of birth control.[191]

Time–concentration curves

-

MPA levels with 2.5 or 5 mg/day oral MPA in combination with 1 or 2 mg/day estradiol valerate (Indivina) in postmenopausal women.[198]

-

MPA levels after a single 150 mg intramuscular injection of MPA (Depo-Provera) in aqueous suspension in women.[199][200]

-

MPA levels after a single 25 to 150 mg intramuscular injection of MPA (Depo-Provera) in aqueous suspension in women.[199][201]

-

MPA levels after a single 104 mg subcutaneous injection of MPA (Depo-SubQ Provera) in aqueous suspension in women.[11]

Chemistry

MPA is a synthetic pregnane steroid and a derivative of progesterone and 17α-hydroxyprogesterone.[202][2] Specifically, it is the 17α-acetate ester of medroxyprogesterone or the 6α-methylated analogue of hydroxyprogesterone acetate.[202][2] MPA is known chemically as 6α-methyl-17α-acetoxyprogesterone or as 6α-methyl-17α-acetoxypregn-4-ene-3,20-dione, and its generic name is a contraction of 6α-methyl-17α-hydroxyprogesterone acetate.[202][2] MPA is closely related to other 17α-hydroxyprogesterone derivatives such as chlormadinone acetate, cyproterone acetate, and megestrol acetate, as well as to medrogestone and nomegestrol acetate.[202][2] 9α-Fluoromedroxyprogesterone acetate (FMPA), the C9α fluoro analogue of MPA and an angiogenesis inhibitor with two orders of magnitude greater potency in comparison to MPA, was investigated for the potential treatment of cancers but was never marketed.[203][204]

History

MPA was independently discovered in 1956 by Syntex and the Upjohn Company.[16][17][205][206] It was first introduced on 18 June 1959 by Upjohn in the United States under the brand name Provera (2.5, 5, and 10 mg tablets) for the treatment of amenorrhea, metrorrhagia, and recurrent miscarriage.[207][208] An intramuscular formulation of MPA, now known as DMPA (400 mg/mL MPA), was also introduced, under the brand name brand name Depo-Provera, in 1960 in the U.S. for the treatment of endometrial and renal cancer.[33] MPA in combination with ethinylestradiol was introduced in 1964 by Upjohn in the U.S. under the brand name Provest (10 mg MPA and 50 μg ethinylestradiol tablets) as an oral contraceptive, but this formulation was discontinued in 1970.[209][210][135] This formulation was marketed by Upjohn outside of the U.S. under the brand names Provestral and Provestrol, while Cyclo-Farlutal (or Ciclofarlutal) and Nogest-S[211] were formulations available outside of the U.S. with a different dosage (5 mg MPA and 50 or 75 μg ethinylestradiol tablets).[212][213]

Following its development in the late 1950s, DMPA was first assessed in clinical trials for use as an injectable contraceptive in 1963.[214] Upjohn sought FDA approval of intramuscular DMPA as a long-acting contraceptive under the brand name Depo-Provera (150 mg/mL MPA) in 1967, but the application was rejected.[215][216] However, this formulation was successfully introduced in countries outside of the United States for the first time in 1969, and was available in over 90 countries worldwide by 1992.[41] Upjohn attempted to gain FDA approval of DMPA as a contraceptive again in 1978, and yet again in 1983, but both applications failed similarly to the 1967 application.[215][216] However, in 1992, the medication was finally approved by the FDA, under the brand name Depo-Provera, for use in contraception.[215] A subcutaneous formulation of DMPA was introduced in the United States as a contraceptive under the brand name Depo-SubQ Provera 104 (104 mg/0.65 mL MPA) in December 2004, and subsequently was also approved for the treatment of endometriosis-related pelvic pain.[217]

MPA has also been marketed widely throughout the world under numerous other brand names such as Farlutal, Perlutex, and Gestapuran, among others.[2][12]

Society and culture

Cost

The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$0.59–1.57 per vial.[19] In the United Kingdom this dose costs the NHS about £6.01.[20] In the United States it costs less than $25 a dose as of 2015.[21] In 2017, it was the 222nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than two million prescriptions.[26][27]

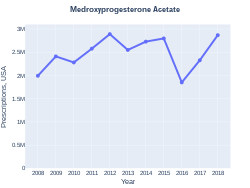

-

Medroxyprogesterone acetate costs (US)

-

Medroxyprogesterone acetate prescriptions (US)

Generic names

Medroxyprogesterone acetate is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, BAN, and JAN, while medrossiprogesterone is the DCIT and médroxyprogestérone the DCF of its free alcohol form.[202][13][2][218][12] It is also known as 6α-methyl-17α-acetoxyprogesterone (MAP) or 6α-methyl-17α-hydroxyprogesterone acetate.[202][13][2][12] Other names include methylacetoxy

Brand names

MPA is marketed under a large number of brand names throughout the world.[12][13][2] Its most major brand names are Provera as oral tablets and Depo-Provera as an aqueous suspension for intramuscular injection.[12][13][2] A formulation of MPA as an aqueous suspension for subcutaneous injection is also available in the United States under the brand name Depo-SubQ Provera 104.[12][13] Other brand names of MPA formulated alone include Farlutal and Sayana for clinical use and Depo-Promone, Perlutex, Promone-E, and Veramix for veterinary use.[12][13][2] In addition to single-drug formulations, MPA is marketed in combination with the estrogens CEEs, estradiol, and estradiol valerate.[12][13][2] Brand names of MPA in combination with CEEs as oral tablets in different countries include Prempro, Premphase, Premique, Premia, and Premelle.[12][13][2] Brand names of MPA in combination with estradiol as oral tablets include Indivina and Tridestra.[12][13][2]

Availability

Oral MPA and DMPA are widely available throughout the world.[12] Oral MPA is available both alone and in combination with the estrogens CEEs, estradiol, and estradiol valerate.[12] DMPA is registered for use as a form of birth control in more than 100 countries worldwide.[24][25][12] The combination of injected MPA and estradiol cypionate is approved for use as a form of birth control in 18 countries.[24]

United States

As of November 2016[update], MPA is available in the United States in the following formulations:[69]

- Oral pills: Amen, Curretab, Cycrin, Provera – 2.5 mg, 5 mg, 10 mg

- Aqueous suspension for intramuscular injection: Depo-Provera – 150 mg/mL (for contraception), 400 mg/mL (for cancer)

- Aqueous suspension for subcutaneous injection: Depo-SubQ Provera 104 – 104 mg/0.65 mL (for contraception)

It is also available in combination with an estrogen in the following formulations:

- Oral pills: CEEs and MPA (Prempro, Prempro (Premarin, Cycrin), Premphase (Premarin, Cycrin 14/14), Premphase 14/14, Prempro/Premphase) – 0.3 mg / 1.5 mg; 0.45 mg / 1.5 mg; 0.625 mg / 2.5 mg; 0.625 mg / 5 mg

While the following formulations have been discontinued:

- Oral pills: ethinylestradiol and MPA (Provest) – 50 μg / 10 mg

- Aqueous suspension for intramuscular injection: estradiol cypionate and MPA (Lunelle) – 5 mg / 25 mg (for contraception)

The state of Louisiana permits sex offenders to be given MPA.[219]

Generation

Progestins in birth control pills are sometimes grouped by generation.[220][221] While the 19-nortestosterone progestins are consistently grouped into generations, the pregnane progestins that are or have been used in birth control pills are typically omitted from such classifications or are grouped simply as "miscellaneous" or "pregnanes".[220][221] In any case, based on its date of introduction in such formulations of 1964, MPA could be considered a "first-generation" progestin.[222]

Controversy

Outside the United States

- In 1994, when DMPA was approved in India, India's Economic and Political Weekly reported that "The FDA finally licensed the drug in 1990 in response to concerns about the population explosion in the third world and the reluctance of third world governments to license a drug not licensed in its originating country." [223] Some scientists and women's groups in India continue to oppose DMPA.[224] In 2016, India introduced DMPA depo-medroxyprogesterone IM preparation in the public health system.[225]

- The Canadian Coalition on Depo-Provera, a coalition of women's health professional and advocacy groups, opposed the approval of DMPA in Canada.[226] Since the approval of DMPA in Canada in 1997, a $700 million class-action lawsuit has been filed against Pfizer by users of DMPA who developed osteoporosis. In response, Pfizer argued that it had met its obligation to disclose and discuss the risks of DMPA with the Canadian medical community.[227]

- Clinical trials for this medication regarding women in Zimbabwe were controversial with regard to human rights abuses and Medical Experimentation in Africa.

- A controversy erupted in Israel when the government was accused of giving DMPA to Ethiopian immigrants without their consent. Some women claimed they were told it was a vaccination. The Israeli government denied the accusations but instructed the four health maintenance organizations to stop administering DMPA injections to women "if there is the slightest doubt that they have not understood the implications of the treatment".[228]

United States

There was a long, controversial history regarding the approval of DMPA by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The original manufacturer, Upjohn, applied repeatedly for approval. FDA advisory committees unanimously recommended approval in 1973, 1975 and 1992, as did the FDA's professional medical staff, but the FDA repeatedly denied approval. Ultimately, on October 29, 1992, the FDA approved DMPA for birth control, which had by then been used by over 30 million women since 1969 and was approved and being used by nearly 9 million women in more than 90 countries, including the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Sweden, Thailand, New Zealand and Indonesia.[229] Points in the controversy included:

- Animal testing for carcinogenicity – DMPA caused breast cancer tumors in dogs. Critics of the study claimed that dogs are more sensitive to artificial progesterone, and that the doses were too high to extrapolate to humans. The FDA pointed out that all substances carcinogenic to humans are carcinogenic to animals as well, and that if a substance is not carcinogenic it does not register as a carcinogen at high doses. Levels of DMPA which caused malignant mammary tumors in dogs were equivalent to 25 times the amount of the normal luteal phase progesterone level for dogs. This is lower than the pregnancy level of progesterone for dogs, and is species-specific.[230]

DMPA caused endometrial cancer in monkeys – 2 of 12 monkeys tested, the first ever recorded cases of endometrial cancer in rhesus monkeys.[231] However, subsequent studies have shown that in humans, DMPA reduces the risk of endometrial cancer by approximately 80%.[56][57][58]

Speaking in comparative terms regarding animal studies of carcinogenicity for medications, a member of the FDA's Bureau of Drugs testified at an agency DMPA hearing, "...Animal data for this drug is more worrisome than any other drug we know of that is to be given to well people." - Cervical cancer in Upjohn/NCI studies. Cervical cancer was found to be increased as high as 9-fold in the first human studies recorded by the manufacturer and the National Cancer Institute.[232] However, numerous larger subsequent studies have shown that DMPA use does not increase the risk of cervical cancer.[233][234][235][236][237]

- Coercion and lack of informed consent. Testing or use of DMPA was focused almost exclusively on women in developing countries and poor women in the United States,[238] raising serious questions about coercion and lack of informed consent, particularly for the illiterate[239] and for the mentally challenged, who in some reported cases were given DMPA long-term for reasons of "menstrual hygiene", although they were not sexually active.[240]

- Atlanta/Grady Study – Upjohn studied the effect of DMPA for 11 years in Atlanta, mostly on black women who were receiving public assistance, but did not file any of the required follow-up reports with the FDA. Investigators who eventually visited noted that the studies were disorganized. "They found that data collection was questionable, consent forms and protocol were absent; that those women whose consent had been obtained at all were not told of possible side effects. Women whose known medical conditions indicated that use of DMPA would endanger their health were given the shot. Several of the women in the study died; some of cancer, but some for other reasons, such as suicide due to depression. Over half the 13,000 women in the study were lost to followup due to sloppy record keeping." Consequently, no data from this study was usable.[238]

- WHO Review – In 1992, the WHO presented a review of DMPA in four developing countries to the FDA. The National Women's Health Network and other women's organizations testified at the hearing that the WHO was not objective, as the WHO had already distributed DMPA in developing countries. DMPA was approved for use in United States on the basis of the WHO review of previously submitted evidence from countries such as Thailand, evidence which the FDA had deemed insufficient and too poorly designed for assessment of cancer risk at a prior hearing.

- The Alan Guttmacher Institute has speculated that United States approval of DMPA may increase its availability and acceptability in developing countries.[238][241]

- In 1995, several women's health groups asked the FDA to put a moratorium on DMPA, and to institute standardized informed consent forms.[242]

Research

DMPA was studied by Upjohn for use as a progestogen-only injectable contraceptive in women at a dose of 50 mg once a month but produced poor cycle control and was not marketed for this use at this dosage.[243] A combination of DMPA and polyestradiol phosphate, an estrogen and long-lasting prodrug of estradiol, was studied in women as a combined injectable contraceptive for use by intramuscular injection once every three months.[244][245][246]

High-dose oral and intramuscular MPA monotherapy has been studied in the treatment of prostate cancer but was found to be inferior to monotherapy with cyproterone acetate or diethylstilbestrol.[247][248][249] High-dose oral MPA has been studied in combination with diethylstilbestrol and CEEs as an addition to high-dose estrogen therapy for the treatment of prostate cancer in men, but was not found to provide better effectiveness than diethylstilbestrol alone.[250]

DMPA has been studied for use as a potential male hormonal contraceptive in combination with the androgens/anabolic steroids testosterone and nandrolone (19-nortestosterone) in men.[251] However, it was never approved for this indication.[251]

MPA was investigated by InKine Pharmaceutical, Salix Pharmaceuticals, and the University of Pennsylvania as a potential anti-inflammatory medication for the treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, Crohn's disease, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, and ulcerative colitis, but did not complete clinical development and was never approved for these indications.[252][253] It was formulated as an oral medication at very high dosages, and was thought to inhibit the signaling of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha, with a mechanism of action that was said to be similar to that of corticosteroids.[252][253] The formulation of MPA had the tentative brand names Colirest and Hematrol for these indications.[252]

MPA has been found to be effective in the treatment of manic symptoms in women with bipolar disorder.[254]

Veterinary use

MPA has been used to reduce aggression and spraying in male cats.[255] It may be particularly useful for controlling such behaviors in neutered male cats.[255] The medication can be administered in cats as an injection once per month.[255]

See also

- Conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate

- Estradiol/medroxyprogesterone acetate

- Estradiol cypionate/medroxyprogesterone acetate

- Polyestradiol phosphate/medroxyprogesterone acetate

Notes

References

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2018-08-03. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 638–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Archived from the original on 2013-06-19.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "MEDROXYPROGESTERONE injectable - Essential drugs". medicalguidelines.msf.org. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 "Medroxyprogesterone Acetate". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-22. Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Schindler AE, Campagnoli C, Druckmann R, Huber J, Pasqualini JR, Schweppe KW, Thijssen JH (2008). "Classification and pharmacology of progestins". Maturitas. 61 (1–2): 171–80. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.11.013. PMID 19434889.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 "Provera" (PDF). FDA. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 Stanczyk FZ, Bhavnani BR (September 2015). "Reprint of "Use of medroxyprogesterone acetate for hormone therapy in postmenopausal women: Is it safe?"". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 153: 151–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2015.08.013. PMID 26291834.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Depo_Provera" (PDF). FDA. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "depo-subQ Provera" (PDF). FDA. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2018. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "DepoSubQProveraLabel" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2018-08-03. Retrieved 2017-11-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 2113–2114. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2018-04-01.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Kemppainen JA, Langley E, Wong CI, Bobseine K, Kelce WR, Wilson EM (March 1999). "Distinguishing androgen receptor agonists and antagonists: distinct mechanisms of activation by medroxyprogesterone acetate and dihydrotestosterone". Molecular Endocrinology. 13 (3): 440–54. doi:10.1210/mend.13.3.0255. PMID 10077001.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ 15.0 15.1 Genazzani AR (15 January 1993). Frontiers in Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. Taylor & Francis. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-85070-486-7. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Stanley M. Roberts (7 May 2013). Introduction to Biological and Small Molecule Drug Research and Development: Chapter 12. Hormone replacement therapy. Elsevier Science. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-0-12-806202-9. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

[...] medroxyprogesterone acetate, also known as Provera® (discovered simultaneously by Searle and Upjohn in 1956) [..]

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Sneader, Walter (2005). "Chapter 18: Hormone analogs". Drug discovery: a history. New York: Wiley. p. 204. ISBN 0-471-89980-1.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Medroxyprogesterone Acetate". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 22 January 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 British National Formulary : BNF 69 (69th ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 555. ISBN 978-0-85711-156-2.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 363. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ A. Wayne Meikle (1 June 1999). Hormone Replacement Therapy. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 383–. ISBN 978-1-59259-700-0. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ Special Programme of Research, Development, and Research Training in Human Reproduction (World Health Organization); World Health Organization (2002). Research on Reproductive Health at WHO: Biennial Report 2000-2001. World Health Organization. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-92-4-156208-9. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2018-07-20.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Bagade O, Pawar V, Patel R, Patel B, Awasarkar V, Diwate S (2014). "Increasing use of long-acting reversible contraception: safe, reliable, and cost-effective birth control" (PDF). World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 3 (10): 364–392. ISSN 2278-4357. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-10. Retrieved 2018-08-02.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Sulochana Gunasheela (14 March 2011). Practical Management of Gynecological Problems. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-93-5025-240-6. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Medroxyprogesterone Acetate - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ Furness S, Roberts H, Marjoribanks J, Lethaby A (August 2012). "Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women and risk of endometrial hyperplasia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD000402. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000402.pub4. PMC 7039145. PMID 22895916.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Medroxyprogesterone". MedlinePlus. 2008-01-09. Archived from the original on 2010-07-12. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Panay N, Fenton A (February 2010). "Bioidentical hormones: what is all the hype about?". Climacteric. 13 (1): 1–3. doi:10.3109/13697130903550250. PMID 20067429.

- ↑ Light SA, Holroyd S (March 2006). "The use of medroxyprogesterone acetate for the treatment of sexually inappropriate behaviour in patients with dementia" (PDF). Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 31 (2): 132–4. PMC 1413960. PMID 16575429. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-07.

- ↑ "The chemical knife". Archived from the original on 2009-01-07. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Depo-Provera (medroxyprogesterone acetate) (NDA # 012541) - Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products, archived from the original on 28 June 2017, retrieved 2 April 2018,

Original Approvals or Tentative Approvals: 09/23/1960.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Meyler L (2009). Meyler's side effects of endocrine and metabolic drugs. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. pp. 281–284]. ISBN 978-0-444-53271-8. Archived from the original on 2014-10-23.