Pregnancy

| Pregnancy | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Gestation | |

| |

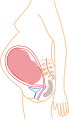

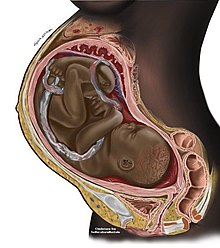

| A woman in the third trimester of pregnancy | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics, midwifery |

| Symptoms | Missed periods, tender breasts, nausea and vomiting, hunger, frequent urination[1] |

| Complications | Miscarriage, high blood pressure of pregnancy, gestational diabetes, iron-deficiency anemia, severe nausea and vomiting[2][3] |

| Duration | ~40 weeks from the last menstrual period[4][5] |

| Causes | Sexual intercourse, assisted reproductive technology[6] |

| Diagnostic method | Pregnancy test[7] |

| Prevention | Birth control (including emergency contraception)[8] |

| Treatment | Prenatal care,[9] abortion[8] |

| Medication | Folic acid, iron supplements[9][10] |

| Frequency | 213 million (2012)[11] |

| Deaths | |

Pregnancy, also known as gestation, is the time during which one or more offspring develops inside a woman.[4] A multiple pregnancy involves more than one offspring, such as with twins.[13] Pregnancy usually occurs by sexual intercourse, but can occur through assisted reproductive technology.[6] A pregnancy may end in a live birth, miscarriage, induced abortion, or a stillbirth. Childbirth typically occurs around 40 weeks from the start of the last menstrual period (LMP).[4][5] This is just over nine months – (gestational age) where each month averages 31 days.[4][5] When using fertilization age it is about 38 weeks.[5] An embryo is the developing offspring during the first eight weeks following fertilization, (ten weeks gestational age) after which, the term fetus is used until birth.[5] Symptoms of early pregnancy may include missed periods, tender breasts, nausea and vomiting, hunger, and frequent urination.[1] Pregnancy may be confirmed with a pregnancy test.[7]

Pregnancy is divided into three trimesters, each lasting for approximately 3 months.[4] The first trimester includes conception, which is when the sperm fertilizes the egg.[4] The fertilized egg then travels down the fallopian tube and attaches to the inside of the uterus, where it begins to form the embryo and placenta.[4] During the first trimester, the possibility of miscarriage (natural death of embryo or fetus) is at its highest.[2] Around the middle of the second trimester, movement of the fetus may be felt.[4] At 28 weeks, more than 90% of babies can survive outside of the uterus if provided with high-quality medical care.[4]

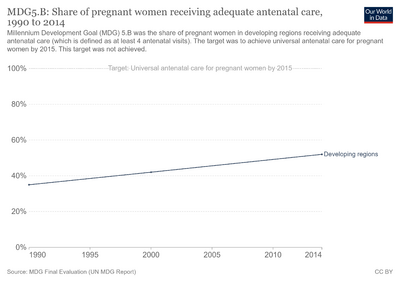

Prenatal care improves pregnancy outcomes.[9] Prenatal care may include taking extra folic acid, avoiding drugs, tobacco smoking, and alcohol, taking regular exercise, having blood tests, and regular physical examinations.[9] Complications of pregnancy may include disorders of high blood pressure, gestational diabetes, iron-deficiency anemia, and severe nausea and vomiting.[3] In the ideal childbirth labor begins on its own when a woman is "at term".[14] Babies born before 37 weeks are "preterm" and at higher risk of health problems such as cerebral palsy.[4] Babies born between weeks 37 and 39 are considered "early term" while those born between weeks 39 and 41 are considered "full term".[4] Babies born between weeks 41 and 42 weeks are considered "late term" while after 42 week they are considered "post term".[4] Delivery before 39 weeks by labor induction or caesarean section is not recommended unless required for other medical reasons.[15]

About 213 million pregnancies occurred in 2012, of which, 190 million (89%) were in the developing world and 23 million (11%) were in the developed world.[11] The number of pregnancies in women aged between 15 and 44 is 133 per 1,000 women.[11] About 10% to 15% of recognized pregnancies end in miscarriage.[2] In 2016, complications of pregnancy resulted in 230,600 maternal deaths, down from 377,000 deaths in 1990.[12] Common causes include bleeding, infections, hypertensive diseases of pregnancy, obstructed labor, and complications associated with miscarriage, abortion, or ectopic pregnancy.[12] Globally, 44% of pregnancies are unplanned.[16] Over half (56%) of unplanned pregnancies are aborted.[16] Among unintended pregnancies in the United States, 60% of the women used birth control to some extent during the month pregnancy occurred.[17]

Terminology

Associated terms for pregnancy are gravid and parous. Gravidus and gravid come from the Latin word meaning "heavy" and a pregnant female is sometimes referred to as a gravida.[18] Gravidity refers to the number of times that a female has been pregnant. Similarly, the term parity is used for the number of times that a female carries a pregnancy to a viable stage.[19] Twins and other multiple births are counted as one pregnancy and birth. A woman who has never been pregnant is referred to as a nulligravida. A woman who is (or has been only) pregnant for the first time is referred to as a primigravida,[20] and a woman in subsequent pregnancies as a multigravida or as multiparous.[18][21] Therefore, during a second pregnancy a woman would be described as gravida 2, para 1 and upon live delivery as gravida 2, para 2. In-progress pregnancies, abortions, miscarriages and/or stillbirths account for parity values being less than the gravida number. In the case of a multiple birth the gravida number and parity value are increased by one only. Women who have never carried a pregnancy achieving more than 20 weeks of gestation age are referred to as nulliparous.[22]

A pregnancy is considered term at 37 weeks of gestation. It is preterm if less than 37 weeks and postterm at or beyond 42 weeks of gestation. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have recommended further division with early term 37 weeks up to 39 weeks, full term 39 weeks up to 41 weeks, and late term 41 weeks up to 42 weeks.[23] The terms preterm and postterm have largely replaced earlier terms of premature and postmature. Preterm and postterm are defined above, whereas premature and postmature have historical meaning and relate more to the infant's size and state of development rather than to the stage of pregnancy.[24][25]

Signs and symptoms

The usual symptoms and discomforts of pregnancy do not significantly interfere with activities of daily living or pose a health-threat to the mother or baby. However, pregnancy complications can cause other more severe symptoms, such as those associated with anemia.

Common symptoms and discomforts of pregnancy include:

- Tiredness

- Morning sickness

- Constipation

- Pelvic girdle pain

- Back pain

- Braxton Hicks contractions. Occasional, irregular, and often painless contractions that occur several times per day.

- Peripheral edema swelling of the lower limbs. Common complaint in advancing pregnancy. Can be caused by inferior vena cava syndrome resulting from compression of the inferior vena cava and pelvic veins by the uterus leading to increased hydrostatic pressure in lower extremities.

- Low blood pressure often caused by compression of both the inferior vena cava and the abdominal aorta (aortocaval compression syndrome).

- Increased urinary frequency. A common complaint, caused by increased intravascular volume, elevated glomerular filtration rate, and compression of the bladder by the expanding uterus.

- Urinary tract infection[26]

- Varicose veins. Common complaint caused by relaxation of the venous smooth muscle and increased intravascular pressure.

- Hemorrhoids (piles). Swollen veins at or inside the anal area. Caused by impaired venous return, straining associated with constipation, or increased intra-abdominal pressure in later pregnancy.[27]

- Regurgitation, heartburn, and nausea.

- Stretch marks

- Breast tenderness is common during the first trimester, and is more common in women who are pregnant at a young age.[28]

- Melasma, also known as the mask of pregnancy, is a discoloration, most often of the face. It usually begins to fade several months after giving birth.

Chronology

The chronology of pregnancy is, unless otherwise specified, generally given as gestational age, where the starting point is the beginning of the woman's last menstrual period (LMP), or the corresponding age of the gestation as estimated by a more accurate method if available. Sometimes, timing may also use the fertilization age which is the age of the embryo.

Start of gestational age

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend the following methods to calculate gestational age:[29]

- Directly calculating the days since the beginning of the last menstrual period.

- Early obstetric ultrasound, comparing the size of an embryo or fetus to that of a reference group of pregnancies of known gestational age (such as calculated from last menstrual periods), and using the mean gestational age of other embryos or fetuses of the same size. If the gestational age as calculated from an early ultrasound is contradictory to the one calculated directly from the last menstrual period, it is still the one from the early ultrasound that is used for the rest of the pregnancy.[29]

- In case of in vitro fertilization, calculating days since oocyte retrieval or co-incubation and adding 14 days.[30]

Trimesters

Pregnancy is divided into three trimesters, each lasting for approximately 3 months.[4] The exact length of each trimester can vary between sources.

- The first trimester begins with the start of gestational age as described above, that is, the beginning of week 1, or 0 weeks + 0 days of gestational age (GA). It ends at week 12 (11 weeks + 6 days of GA)[4] or end of week 14 (13 weeks + 6 days of GA).[31]

- The second trimester is defined as starting, between the beginning of week 13 (12 weeks +0 days of GA)[4] and beginning of week 15 (14 weeks + 0 days of GA).[31] It ends at the end of week 27 (26 weeks + 6 days of GA)[31] or end of week 28 (27 weeks + 6 days of GA).[4]

- The third trimester is defined as starting, between the beginning of week 28 (27 weeks + 0 days of GA)[31] or beginning of week 29 (28 weeks + 0 days of GA).[4] It lasts until childbirth.

Estimation of due date

Due date estimation basically follows two steps:

- Determination of which time point is to be used as origin for gestational age, as described in the section above.

- Adding the estimated gestational age at childbirth to the above time point. Childbirth on average occurs at a gestational age of 280 days (40 weeks), which is therefore often used as a standard estimation for individual pregnancies.[33] However, alternative durations as well as more individualized methods have also been suggested.

Naegele's rule is a standard way of calculating the due date for a pregnancy when assuming a gestational age of 280 days at childbirth. The rule estimates the expected date of delivery (EDD) by adding a year, subtracting three months, and adding seven days to the origin of gestational age. Alternatively there are mobile apps, which essentially always give consistent estimations compared to each other and correct for leap year, while pregnancy wheels made of paper can differ from each other by 7 days and generally do not correct for leap year.[34]

Furthermore, actual childbirth has only a certain probability of occurring within the limits of the estimated due date. A study of singleton live births came to the result that childbirth has a standard deviation of 14 days when gestational age is estimated by first trimester ultrasound, and 16 days when estimated directly by last menstrual period.[32]

Physiology

Initiation

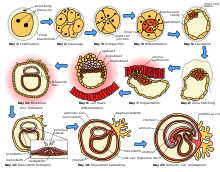

Through an interplay of hormones that includes follicle stimulating hormone that stimulates folliculogenesis and oogenesis creates a mature egg cell, the female gamete. Fertilization is the event where the egg cell fuses with the male gamete, spermatozoon. After the point of fertilization, the fused product of the female and male gamete is referred to as a zygote or fertilized egg. The fusion of female and male gametes usually occurs following the act of sexual intercourse. Pregnancy rates for sexual intercourse are highest during the menstrual cycle time from some 5 days before until 1 to 2 days after ovulation.[35] Fertilization can also occur by assisted reproductive technology such as artificial insemination and in vitro fertilisation.

Fertilization (conception) is sometimes used as the initiation of pregnancy, with the derived age being termed fertilization age. Fertilization usually occurs about two weeks before the next expected menstrual period.

A third point in time is also considered by some people to be the true beginning of a pregnancy: This is time of implantation, when the future fetus attaches to the lining of the uterus. This is about a week to ten days after fertilization.[36]

Development of embryo and fetus

The sperm and the egg cell, which has been released from one of the female's two ovaries, unite in one of the two fallopian tubes. The fertilized egg, known as a zygote, then moves toward the uterus, a journey that can take up to a week to complete. Cell division begins approximately 24 to 36 hours after the female and male cells unite. Cell division continues at a rapid rate and the cells then develop into what is known as a blastocyst. The blastocyst arrives at the uterus and attaches to the uterine wall, a process known as implantation.

The development of the mass of cells that will become the infant is called embryogenesis during the first approximately ten weeks of gestation. During this time, cells begin to differentiate into the various body systems. The basic outlines of the organ, body, and nervous systems are established. By the end of the embryonic stage, the beginnings of features such as fingers, eyes, mouth, and ears become visible. Also during this time, there is development of structures important to the support of the embryo, including the placenta and umbilical cord. The placenta connects the developing embryo to the uterine wall to allow nutrient uptake, waste elimination, and gas exchange via the mother's blood supply. The umbilical cord is the connecting cord from the embryo or fetus to the placenta.

After about ten weeks of gestational age – which is the same as eight weeks after conception – the embryo becomes known as a fetus.[37] At the beginning of the fetal stage, the risk of miscarriage decreases sharply.[38] At this stage, a fetus is about 30 mm (1.2 inches) in length, the heartbeat is seen via ultrasound, and the fetus makes involuntary motions.[39] During continued fetal development, the early body systems, and structures that were established in the embryonic stage continue to develop. Sex organs begin to appear during the third month of gestation. The fetus continues to grow in both weight and length, although the majority of the physical growth occurs in the last weeks of pregnancy.

Electrical brain activity is first detected between the fifth and sixth week of gestation. It is considered primitive neural activity rather than the beginning of conscious thought. Synapses begin forming at 17 weeks, and begin to multiply quickly at week 28 until 3 to 4 months after birth.[40]

Although the fetus begins to move during the first trimester, it is not until the second trimester that movement, known as quickening, can be felt. This typically happens in the fourth month, more specifically in the 20th to 21st week, or by the 19th week if the woman has been pregnant before. It is common for some women not to feel the fetus move until much later. During the second trimester, most women begin to wear maternity clothes.

-

Embryo at 4 weeks after fertilization. (Gestational age of 6 weeks.)

-

Fetus at 8 weeks after fertilization. (Gestational age of 10 weeks.)

-

Fetus at 18 weeks after fertilization. (Gestational age of 20 weeks.)

-

Fetus at 38 weeks after fertilization. (Gestational age of 40 weeks.)

-

Relative size in 1st month (simplified illustration)

-

Relative size in 3rd month (simplified illustration)

-

Relative size in 5th month (simplified illustration)

-

Relative size in 9th month (simplified illustration)

Maternal changes

During pregnancy, a woman undergoes many physiological changes, which are entirely normal, including behavioral, cardiovascular, hematologic, metabolic, renal, and respiratory changes. Increases in blood sugar, breathing, and cardiac output are all required. Levels of progesterone and estrogens rise continually throughout pregnancy, suppressing the hypothalamic axis and therefore also the menstrual cycle. A full-term pregnancy at an early age reduces the risk of breast, ovarian and endometrial cancer and the risk declines further with each additional full-term pregnancy.[41][42]

The fetus is genetically different from its mother, and can be viewed as an unusually successful allograft.[43] The main reason for this success is increased immune tolerance during pregnancy.[44] Immune tolerance is the concept that the body is able to not mount an immune system response against certain triggers.[43]

During the first trimester, minute ventilation increases by 40%.[45] The womb will grow to the size of a lemon by eight weeks. Many symptoms and discomforts of pregnancy like nausea and tender breasts appear in the first trimester.[46]

During the second trimester, most women feel more energized, and begin to put on weight as the symptoms of morning sickness subside and eventually fade away. The uterus, the muscular organ that holds the developing fetus, can expand up to 20 times its normal size during pregnancy.

Final weight gain takes place during the third trimester, which is the most weight gain throughout the pregnancy. The woman's abdomen will transform in shape as it drops due to the fetus turning in a downward position ready for birth. During the second trimester, the woman's abdomen would have been upright, whereas in the third trimester it will drop down low. The fetus moves regularly, and is felt by the woman. Fetal movement can become strong and be disruptive to the woman. The woman's navel will sometimes become convex, "popping" out, due to the expanding abdomen.

Head engagement, where the fetal head descends into cephalic presentation, relieves pressure on the upper abdomen with renewed ease in breathing. It also severely reduces bladder capacity, and increases pressure on the pelvic floor and the rectum.

It is also during the third trimester that maternal activity and sleep positions may affect fetal development due to restricted blood flow. For instance, the enlarged uterus may impede blood flow by compressing the vena cava when lying flat, which is relieved by lying on the left side.[47]

Childbirth

Childbirth, referred to as labor and delivery in the medical field, is the process whereby an infant is born.[48]

A woman is considered to be in labour when she begins experiencing regular uterine contractions, accompanied by changes of her cervix – primarily effacement and dilation. While childbirth is widely experienced as painful, some women do report painless labours, while others find that concentrating on the birth helps to quicken labour and lessen the sensations. Most births are successful vaginal births, but sometimes complications arise and a woman may undergo a cesarean section.

During the time immediately after birth, both the mother and the baby are hormonally cued to bond, the mother through the release of oxytocin, a hormone also released during breastfeeding. Studies show that skin-to-skin contact between a mother and her newborn immediately after birth is beneficial for both the mother and baby. A review done by the World Health Organization found that skin-to-skin contact between mothers and babies after birth reduces crying, improves mother–infant interaction, and helps mothers to breastfeed successfully. They recommend that neonates be allowed to bond with the mother during their first two hours after birth, the period that they tend to be more alert than in the following hours of early life.[49]

Childbirth maturity stages

| stage | starts | ends |

|---|---|---|

| Preterm[50] | - | at 37 weeks |

| Early term[51] | 37 weeks | 39 weeks |

| Full term[51] | 39 weeks | 41 weeks |

| Late term[51] | 41 weeks | 42 weeks |

| Postterm[51] | 42 weeks | - |

In the ideal childbirth labor begins on its own when a woman is "at term".[14] Events before completion of 37 weeks are considered preterm.[50] Preterm birth is associated with a range of complications and should be avoided if possible.[52]

Sometimes if a woman's water breaks or she has contractions before 39 weeks, birth is unavoidable.[51] However, spontaneous birth after 37 weeks is considered term and is not associated with the same risks of a pre-term birth.[48] Planned birth before 39 weeks by caesarean section or labor induction, although "at term", results in an increased risk of complications.[53] This is from factors including underdeveloped lungs of newborns, infection due to underdeveloped immune system, feeding problems due to underdeveloped brain, and jaundice from underdeveloped liver.[54]

Babies born between 39 and 41 weeks gestation have better outcomes than babies born either before or after this range.[51] This special time period is called "full term".[51] Whenever possible, waiting for labor to begin on its own in this time period is best for the health of the mother and baby.[14] The decision to perform an induction must be made after weighing the risks and benefits, but is safer after 39 weeks.[14]

Events after 42 weeks are considered postterm.[51] When a pregnancy exceeds 42 weeks, the risk of complications for both the woman and the fetus increases significantly.[55][56] Therefore, in an otherwise uncomplicated pregnancy, obstetricians usually prefer to induce labour at some stage between 41 and 42 weeks.[57]

Postnatal period

The postnatal period, also referred to as the puerperium, begins immediately after delivery and extends for about six weeks.[48] During this period, the mother's body begins the return to pre-pregnancy conditions that includes changes in hormone levels and uterus size.[48]

Diagnosis

The beginning of pregnancy may be detected either based on symptoms by the woman herself, or by using pregnancy tests. However, an important condition with serious health implications that is quite common is the denial of pregnancy by the pregnant woman. About one in 475 denials will last until around the 20th week of pregnancy. The proportion of cases of denial, persisting until delivery is about 1 in 2500.[58] Conversely, some non-pregnant women have a very strong belief that they are pregnant along with some of the physical changes. This condition is known as a false pregnancy.[59]

Physical signs

Most pregnant women experience a number of symptoms,[60] which can signify pregnancy. A number of early medical signs are associated with pregnancy.[61][62] These signs include:

- the presence of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in the blood and urine

- missed menstrual period

- implantation bleeding that occurs at implantation of the embryo in the uterus during the third or fourth week after last menstrual period

- increased basal body temperature sustained for over 2 weeks after ovulation

- Chadwick's sign (darkening of the cervix, vagina, and vulva)

- Goodell's sign (softening of the vaginal portion of the cervix)

- Hegar's sign (softening of the uterus isthmus)

- Pigmentation of the linea alba – linea nigra, (darkening of the skin in a midline of the abdomen, caused by hyperpigmentation resulting from hormonal changes, usually appearing around the middle of pregnancy).[61][62]

- Darkening of the nipples and areolas due to an increase in hormones.[63]

Biomarkers

Pregnancy detection can be accomplished using one or more various pregnancy tests,[64] which detect hormones generated by the newly formed placenta, serving as biomarkers of pregnancy.[65] Blood and urine tests can detect pregnancy 12 days after implantation.[66] Blood pregnancy tests are more sensitive than urine tests (giving fewer false negatives).[67] Home pregnancy tests are urine tests, and normally detect a pregnancy 12 to 15 days after fertilization.[68] A quantitative blood test can determine approximately the date the embryo was conceived because hCG doubles every 36 to 48 hours.[48] A single test of progesterone levels can also help determine how likely a fetus will survive in those with a threatened miscarriage (bleeding in early pregnancy).[69]

Ultrasound

Obstetric ultrasonography can detect fetal abnormalities, detect multiple pregnancies, and improve gestational dating at 24 weeks.[70] The resultant estimated gestational age and due date of the fetus are slightly more accurate than methods based on last menstrual period.[71] Ultrasound is used to measure the nuchal fold in order to screen for Down syndrome.[72]

Management

Prenatal care

Pre-conception counseling is care that is provided to a woman and/ or couple to discuss conception, pregnancy, current health issues and recommendations for the period before pregnancy.[75]

Prenatal medical care is the medical and nursing care recommended for women during pregnancy, time intervals and exact goals of each visit differ by country.[76] Women who are high risk have better outcomes if they are seen regularly and frequently by a medical professional than women who are low risk.[77] A woman can be labeled as high risk for different reasons including previous complications in pregnancy, complications in the current pregnancy, current medical diseases, or social issues.[78][79]

The aim of good prenatal care is prevention, early identification, and treatment of any medical complications.[80] A basic prenatal visit consists of measurement of blood pressure, fundal height, weight and fetal heart rate, checking for symptoms of labor, and guidance for what to expect next.[75] Testing for gestational diabetes is recommended at 24 weeks and after.[81]

Nutrition

Nutrition during pregnancy is important to ensure healthy growth of the fetus.[82] Nutrition during pregnancy is different from the non-pregnant state.[82] There are increased energy requirements and specific micronutrient requirements.[82] Women benefit from education to encourage a balanced energy and protein intake during pregnancy.[83] Some women may need professional medical advice if their diet is affected by medical conditions, food allergies, or specific religious/ ethical beliefs.[84] Further studies are needed to access the effect of dietary advice to prevent gestational diabetes, although low quality evidence suggests some benefit.[85]

Adequate periconceptional (time before and right after conception) folic acid (also called folate or Vitamin B9) intake has been shown to decrease the risk of fetal neural tube defects, such as spina bifida.[86] The neural tube develops during the first 28 days of pregnancy, a urine pregnancy test is not usually positive until 14 days post-conception, explaining the necessity to guarantee adequate folate intake before conception.[68][87] Folate is abundant in green leafy vegetables, legumes, and citrus.[88] In the United States and Canada, most wheat products (flour, noodles) are fortified with folic acid.[89]

DHA omega-3 is a major structural fatty acid in the brain and retina, and is naturally found in breast milk.[90] It is important for the woman to consume adequate amounts of DHA during pregnancy and while nursing to support her well-being and the health of her infant.[90] Developing infants cannot produce DHA efficiently, and must receive this vital nutrient from the woman through the placenta during pregnancy and in breast milk after birth.[91]

Several micronutrients are important for the health of the developing fetus, especially in areas of the world where insufficient nutrition is common.[10] Women living in low and middle income countries are suggested to take multiple micronutrient supplements containing iron and folic acid.[10] These supplements have been shown to improve birth outcomes in developing countries, but do not have an effect on perinatal mortality.[10][92] Adequate intake of folic acid, and iron is often recommended.[93][94] In developed areas, such as Western Europe and the United States, certain nutrients such as Vitamin D and calcium, required for bone development, may also require supplementation.[95][96][97] Vitamin E supplementation has not been shown to improve birth outcomes.[98] Zinc supplementation has been associated with a decrease in preterm birth, but it is unclear whether it is causative.[99] Daily iron supplementation reduces the risk of maternal anemia.[100] Studies of routine daily iron supplementation for pregnant women found improvement in blood iron levels, without a clear clinical benefit.[101] The nutritional needs for women carrying twins or triplets are higher than those of women carrying one baby.[102]

Women are counseled to avoid certain foods, because of the possibility of contamination with bacteria or parasites that can cause illness.[103] Careful washing of fruits and raw vegetables may remove these pathogens, as may thoroughly cooking leftovers, meat, or processed meat.[104] Unpasteurized dairy and deli meats may contain Listeria, which can cause neonatal meningitis, stillbirth and miscarriage.[105] Pregnant women are also more prone to Salmonella infections, can be in eggs and poultry, which should be thoroughly cooked.[106] Cat feces and undercooked meats may contain the parasite Toxoplasma gondii and can cause toxoplasmosis.[104] Practicing good hygiene in the kitchen can reduce these risks.[107]

Women are also counseled to eat seafood in moderation and to eliminate seafood known to be high in mercury because of the risk of birth defects.[106] Pregnant women are counseled to consume caffeine in moderation, because large amounts of caffeine are associated with miscarriage.[48] However, the relationship between caffeine, birthweight, and preterm birth is unclear.[108]

Weight gain

The amount of healthy weight gain during a pregnancy varies.[109] Weight gain is related to the weight of the baby, the placenta, extra circulatory fluid, larger tissues, and fat and protein stores.[82] Most needed weight gain occurs later in pregnancy.[110]

The Institute of Medicine recommends an overall pregnancy weight gain for those of normal weight (body mass index of 18.5–24.9), of 11.3–15.9 kg (25–35 pounds) having a singleton pregnancy.[111] Women who are underweight (BMI of less than 18.5), should gain between 12.7–18 kg (28–40 lbs), while those who are overweight (BMI of 25–29.9) are advised to gain between 6.8–11.3 kg (15–25 lbs) and those who are obese (BMI>30) should gain between 5–9 kg (11–20 lbs).[112] These values reference the expectations for a term pregnancy.

During pregnancy, insufficient or excessive weight gain can compromise the health of the mother and fetus.[110] The most effective intervention for weight gain in underweight women is not clear.[110] Being or becoming overweight in pregnancy increases the risk of complications for mother and fetus, including cesarean section, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, macrosomia and shoulder dystocia.[109] Excessive weight gain can make losing weight after the pregnancy difficult.[109][113]

Around 50% of women of childbearing age in developed countries like the United Kingdom are overweight or obese before pregnancy.[113] Diet modification is the most effective way to reduce weight gain and associated risks in pregnancy.[113]

Medication

Drugs used during pregnancy can have temporary or permanent effects on the fetus.[114] Anything (including drugs) that can cause permanent deformities in the fetus are labeled as teratogens.[115] In the U.S., drugs were classified into categories A, B, C, D and X based on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rating system to provide therapeutic guidance based on potential benefits and fetal risks.[116] Drugs, including some multivitamins, that have demonstrated no fetal risks after controlled studies in humans are classified as Category A.[114] On the other hand, drugs like thalidomide with proven fetal risks that outweigh all benefits are classified as Category X.[114]

Recreational drugs

The use of recreational drugs in pregnancy can cause various pregnancy complications.[48]

- Ethanol during pregnancy can cause one or more fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.[48] According to the CDC, there is no known safe amount of alcohol during pregnancy and no safe time to drink during pregnancy, including before a woman knows that she is pregnant.[117]

- Tobacco smoking during pregnancy can cause a wide range of behavioral, neurological, and physical difficulties.[118] Smoking during pregnancy causes twice the risk of premature rupture of membranes, placental abruption and placenta previa.[119] Smoking is associated with 30% higher odds of preterm birth.[120]

- Prenatal cocaine exposure is associated with premature birth, birth defects and attention deficit disorder.[48]

- Prenatal methamphetamine exposure can cause premature birth and congenital abnormalities.[121] Short-term neonatal outcomes in metamphetamine babies show small deficits in infant neurobehavioral function and growth restriction.[122] Long-term effects in terms of impaired brain development may also be caused by methamphetamine use.[121]

- Cannabis in pregnancy has been shown to be teratogenic in large doses in animals, but has not shown any teratogenic effects in humans.[48]

Exposure to toxins

Intrauterine exposure to environmental toxins in pregnancy has the potential to cause adverse effects on prenatal development, and to cause pregnancy complications.[48] Air pollution has been associated with low birth weight infants.[123] Conditions of particular severity in pregnancy include mercury poisoning and lead poisoning.[48] To minimize exposure to environmental toxins, the American College of Nurse-Midwives recommends: checking whether the home has lead paint, washing all fresh fruits and vegetables thoroughly and buying organic produce, and avoiding cleaning products labeled "toxic" or any product with a warning on the label.[124]

Pregnant women can also be exposed to toxins in the workplace, including airborne particles. The effects of wearing N95 filtering facepiece respirators are similar for pregnant women as for non-pregnant women, and wearing a respirator for one hour does not affect the fetal heart rate.[125]

Sexual activity

Most women can continue to engage in sexual activity throughout pregnancy.[126] Most research suggests that during pregnancy both sexual desire and frequency of sexual relations decrease.[127][128] In context of this overall decrease in desire, some studies indicate a second-trimester increase, preceding a decrease during the third trimester.[129][130]

Sex during pregnancy is a low-risk behavior except when the healthcare provider advises that sexual intercourse be avoided for particular medical reasons.[126] For a healthy pregnant woman, there is no single safe or right way to have sex during pregnancy.[126] Pregnancy alters the vaginal flora with a reduction in microscopic species/genus diversity.[131]

Exercise

Regular aerobic exercise during pregnancy appears to improve (or maintain) physical fitness.[132] Physical exercise during pregnancy does appear to decrease the need for C-section.[133] Bed rest, outside of research studies, is not recommended as there is no evidence of benefit and potential harm.[134]

The Clinical Practice Obstetrics Committee of Canada recommends that "All women without contraindications should be encouraged to participate in aerobic and strength-conditioning exercises as part of a healthy lifestyle during their pregnancy".[135] Although an upper level of safe exercise intensity has not been established, women who were regular exercisers before pregnancy and who have uncomplicated pregnancies should be able to engage in high intensity exercise programs.[135] In general, participation in a wide range of recreational activities appears to be safe, with the avoidance of those with a high risk of falling such as horseback riding or skiing or those that carry a risk of abdominal trauma, such as soccer or hockey.[136]

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reports that in the past, the main concerns of exercise in pregnancy were focused on the fetus and any potential maternal benefit was thought to be offset by potential risks to the fetus. However, they write that more recent information suggests that in the uncomplicated pregnancy, fetal injuries are highly unlikely.[136] They do, however, list several circumstances when a woman should contact her health care provider before continuing with an exercise program: vaginal bleeding, shortness of breath before exertion, dizziness, headache, chest pain, muscle weakness, preterm labor, decreased fetal movement, amniotic fluid leakage, and calf pain or swelling (to rule out thrombophlebitis).[136]

Sleep

It has been suggested that shift work and exposure to bright light at night should be avoided at least during the last trimester of pregnancy to decrease the risk of psychological and behavioral problems in the newborn.[137]

Dental care

The increased levels of progesterone and estrogen during pregnancy make gingivitis more likely; the gums become edematous, red in colour, and tend to bleed.[138] Also a pyogenic granuloma or “pregnancy tumor,” is commonly seen on the labial surface of the papilla. Lesions can be treated by local debridement or deep incision depending on their size, and by following adequate oral hygiene measures.[139] There have been suggestions that severe periodontitis may increase the risk of having preterm birth and low birth weight, however, a Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to determine if periodontitis can develop adverse birth outcomes.[140]

Flying

In low risk pregnancies, most health care providers approve flying until about 36 weeks of gestational age.[141] Most airlines allow pregnant women to fly short distances at less than 36 weeks, and long distances at less than 32 weeks.[142] Many airlines require a doctor's note that approves flying, specially at over 28 weeks.[142] During flights, the risk of deep vein thrombosis is decreased by getting up and walking occasionally, as well as by avoiding dehydration.[142]

Full body scanners do not use ionizing radiation, and are safe in pregnancy.[143] Airports can also possibly use backscatter X-ray scanners, which use a very low dose, but where safety in pregnancy is not fully established.

Complications

Each year, ill health as a result of pregnancy is experienced (sometimes permanently) by more than 20 million women around the world.[144] In 2016, complications of pregnancy resulted in 230,600 deaths down from 377,000 deaths in 1990.[12] Common causes include bleeding (72,000), infections (20,000), hypertensive diseases of pregnancy (32,000), obstructed labor (10,000), and pregnancy with abortive outcome (20,000), which includes miscarriage, abortion, and ectopic pregnancy.[12]

The following are some examples of pregnancy complications:

- Pregnancy induced hypertension

- Anemia[145]

- Postpartum depression

- Postpartum psychosis

- Thromboembolic disorders, with an increased risk due to hypercoagulability in pregnancy. These are the leading cause of death in pregnant women in the US.[146][147]

- Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP), a skin disease that develops around the 32nd week. Signs are red plaques, papules, and itchiness around the belly button that then spreads all over the body except for the inside of hands and face.

- Ectopic pregnancy, including abdominal pregnancy, implantation of the embryo outside the uterus

- Hyperemesis gravidarum, excessive nausea and vomiting that is more severe than normal morning sickness.

- Pulmonary embolism, a blood clot that forms in the legs and migrates to the lungs.[147]

- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy is a rare complication thought to be brought about by a disruption in the metabolism of fatty acids by mitochondria.

There is also an increased susceptibility and severity of certain infections in pregnancy.

Diseases in pregnancy

A pregnant woman may have a pre-existing disease, which is not directly caused by the pregnancy, but may cause complications to develop that include a potential risk to the pregnancy; or a disease may develop during pregnancy.

- Diabetes mellitus and pregnancy deals with the interactions of diabetes mellitus (not restricted to gestational diabetes) and pregnancy. Risks for the child include miscarriage, growth restriction, growth acceleration, large for gestational age (macrosomia), polyhydramnios (too much amniotic fluid), and birth defects.

- Thyroid disease in pregnancy can, if uncorrected, cause adverse effects on fetal and maternal well-being. The deleterious effects of thyroid dysfunction can also extend beyond pregnancy and delivery to affect neurointellectual development in the early life of the child. Demand for thyroid hormones is increased during pregnancy, which may cause a previously unnoticed thyroid disorder to worsen.

- Untreated celiac disease can cause a miscarriage, intrauterine growth restriction, small for gestational age, low birthweight and preterm birth. Often reproductive disorders are the only manifestation of undiagnosed celiac disease and most cases are not recognized. Complications or failures of pregnancy cannot be explained simply by malabsorption, but by the autoimmune response elicited by the exposure to gluten, which causes damage to the placenta. The gluten-free diet avoids or reduces the risk of developing reproductive disorders in pregnant women with celiac disease.[148][149] Also, pregnancy can be a trigger for the development of celiac disease in genetically susceptible women who are consuming gluten.[150]

- Lupus in pregnancy confers an increased rate of fetal death in utero, miscarriage, and of neonatal lupus.

- Hypercoagulability in pregnancy is the propensity of pregnant women to develop thrombosis (blood clots). Pregnancy itself is a factor of hypercoagulability (pregnancy-induced hypercoagulability), as a physiologically adaptive mechanism to prevent postpartum bleeding.[151] However, in combination with an underlying hypercoagulable state, the risk of thrombosis or embolism may become substantial.[151]

Medical imaging

Medical imaging may be indicated in pregnancy because of pregnancy complications, disease, or routine prenatal care. Medical ultrasonography including obstetric ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) without contrast agents are not associated with any risk for the mother or the fetus, and are the imaging techniques of choice for pregnant women.[152]

Projectional radiography, CT scan and nuclear medicine imaging result in some degree of ionizing radiation exposure, but in most cases the absorbed doses are not associated with harm to the baby.[152]

At higher dosages, effects can include miscarriage, birth defects and intellectual disability.[152]

Epidemiology

About 213 million pregnancies occurred in 2012 of which 190 million were in the developing world and 23 million were in the developed world.[11] This is about 133 pregnancies per 1,000 women aged 15 to 44.[11] About 10% to 15% of recognized pregnancies end in miscarriage.[2] Globally, 44% of pregnancies are unplanned. Over half (56%) of unplanned pregnancies are aborted. In countries where abortion is prohibited, or only carried out in circumstances where the mother's life is at risk, 48% of unplanned pregnancies are aborted illegally. Compared to the rate in countries where abortion is legal, at 69%.[16]

Of pregnancies in 2012, 120 million occurred in Asia, 54 million in Africa, 19 million in Europe, 18 million in Latin America and the Caribbean, 7 million in North America, and 1 million in Oceania.[11] Pregnancy rates are 140 per 1000 women of childbearing age in the developing world and 94 per 1000 in the developed world.[11]

The rate of pregnancy, as well as the ages at which it occurs, differ by country and region. It is influenced by a number of factors, such as cultural, social and religious norms; access to contraception; and rates of education. The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2013 was estimated to be highest in Niger (7.03 children/woman) and lowest in Singapore (0.79 children/woman).[153]

In Europe, the average childbearing age has been rising continuously for some time. In Western, Northern, and Southern Europe, first-time mothers are on average 26 to 29 years old, up from 23 to 25 years at the start of the 1970s. In a number of European countries (Spain), the mean age of women at first childbirth has crossed the 30-year threshold.

This process is not restricted to Europe. Asia, Japan and the United States are all seeing average age at first birth on the rise, and increasingly the process is spreading to countries in the developing world like China, Turkey and Iran. In the US, the average age of first childbirth was 25.4 in 2010.[154]

In the United States and United Kingdom, 40% of pregnancies are unplanned, and between a quarter and half of those unplanned pregnancies were unwanted pregnancies.[155][156]

Society and culture

Visitation, circa 1305

In most cultures, pregnant women have a special status in society and receive particularly gentle care.[157] At the same time, they are subject to expectations that may exert great psychological pressure, such as having to produce a son and heir. In many traditional societies, pregnancy must be preceded by marriage, on pain of ostracism of mother and (illegitimate) child.

Overall, pregnancy is accompanied by numerous customs that are often subject to ethnological research, often rooted in traditional medicine or religion. The baby shower is an example of a modern custom.

Pregnancy is an important topic in sociology of the family. The prospective child may preliminarily be placed into numerous social roles. The parents' relationship and the relation between parents and their surroundings are also affected.

A belly cast may be made during pregnancy as a keepsake.

Arts

Images of pregnant women, especially small figurines, were made in traditional cultures in many places and periods, though it is rarely one of the most common types of image. These include ceramic figures from some Pre-Columbian cultures, and a few figures from most of the ancient Mediterranean cultures. Many of these seem to be connected with fertility. Identifying whether such figures are actually meant to show pregnancy is often a problem, as well as understanding their role in the culture concerned.

Among the oldest surviving examples of the depiction of pregnancy are prehistoric figurines found across much of Eurasia and collectively known as Venus figurines. Some of these appear to be pregnant.

Due to the important role of the Mother of God in Christianity, the Western visual arts have a long tradition of depictions of pregnancy, especially in the biblical scene of the Visitation, and devotional images called a Madonna del Parto.[158]

The unhappy scene usually called Diana and Callisto, showing the moment of discovery of Callisto's forbidden pregnancy, is sometimes painted from the Renaissance onwards. Gradually, portraits of pregnant women began to appear, with a particular fashion for "pregnancy portraits" in elite portraiture of the years around 1600.

Pregnancy, and especially pregnancy of unmarried women, is also an important motif in literature. Notable examples include Hardy's Tess of the d'Urbervilles and Goethe's Faust.

- Pregnancy in art

-

Anatomical model of a pregnant woman; Stephan Zick (1639–1715); 1700; Germanisches Nationalmuseum

-

Statue of a pregnant woman, Macedonia

-

Bronze figure of a pregnant naked woman by Danny Osborne, Merrion Square

-

Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger Portrait of Susanna Temple, second wife of Sir Martin Lister, 1620

-

Octave Tassaert, The Waif aka L'abandonnée 1852, Musée Fabre, Montpellier

Infertility

Modern reproductive medicine offers many forms of assisted reproductive technology for couples who stay childless against their will, such as fertility medication, artificial insemination, in vitro fertilization and surrogacy.

Abortion

An abortion is the termination of an embryo or fetus, either naturally or via medical methods.[159] When carried out by choice, it is usually within the first trimester, sometimes in the second, and rarely in the third.[38] Not using contraception, contraceptive failure, poor family planning or rape can lead to undesired pregnancies. Legality of socially indicated abortions varies widely both internationally and through time. In most countries of Western Europe, abortions during the first trimester were a criminal offense a few decades ago[when?] but have since been legalized, sometimes subject to mandatory consultations. In Germany, for example, as of 2009 less than 3% of abortions had a medical indication.

Legal protection

Many countries have various legal regulations in place to protect pregnant women and their children. Maternity Protection Convention ensures that pregnant women are exempt from activities such as night shifts or carrying heavy stocks. Maternity leave typically provides paid leave from work during roughly the last trimester of pregnancy and for some time after birth. Notable extreme cases include Norway (8 months with full pay) and the United States (no paid leave at all except in some states). Moreover, many countries have laws against pregnancy discrimination.

In the United States, some actions that result in miscarriage or stillbirth are considered crimes. One law that does so is the federal Unborn Victims of Violence Act. In 2014, the American state of Tennessee passed a law which allows prosecutors to charge a woman with criminal assault if she uses illegal drugs during her pregnancy and her fetus or newborn is considered harmed as a result.[160]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "What are some common signs of pregnancy?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 12 July 2013. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 The Johns Hopkins Manual of Gynecology and Obstetrics (4 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2012. p. 438. ISBN 978-1-4511-4801-5. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "What are some common complications of pregnancy?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 12 July 2013. Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 "Pregnancy: Condition Information". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 19 December 2013. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Abman, Steven H. (2011). Fetal and neonatal physiology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-1-4160-3479-7. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Shehan, Constance L. (2016). The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Family Studies, 4 Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-470-65845-1. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "How do I know if I'm pregnant?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 30 November 2012. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Taylor D, James EA (2011). "An evidence-based guideline for unintended pregnancy prevention". Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing. 40 (6): 782–93. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01296.x. PMC 3266470. PMID 22092349.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "What is prenatal care and why is it important?". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 12 July 2013. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Keats, EC; Haider, BA; Tam, E; Bhutta, ZA (14 March 2019). "Multiple-micronutrient supplementation for women during pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD004905. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004905.pub6. PMC 6418471. PMID 30873598.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Sedgh G, Singh S, Hussain R (September 2014). "Intended and unintended pregnancies worldwide in 2012 and recent trends". Studies in Family Planning. 45 (3): 301–314. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2014.00393.x. PMC 4727534. PMID 25207494.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators (September 2017). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". Lancet. 390 (10100): 1151–1210. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32152-9. PMC 5605883. PMID 28919116.

- ↑ Wylie, Linda (2005). Essential anatomy and physiology in maternity care (Second ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-443-10041-3. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (February 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, archived from the original on 1 September 2013, retrieved 1 August 2013

- ↑ World Health Organization (November 2014). "Preterm birth Fact sheet N°363". who.int. Archived from the original on 7 March 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Alkema L, Sedgh G (April 2018). "Global, regional, and subregional trends in unintended pregnancy and its outcomes from 1990 to 2014: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model". The Lancet. Global Health. 6 (4): e380–e389. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30029-9. PMC 6055480. PMID 29519649.

- ↑ Hurt, K Joseph; Guile, Matthew W.; Bienstock, Jessica L.; Fox, Harold E.; Wallach, Edward E. (28 March 2012). The Johns Hopkins manual of gynecology and obstetrics (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health / Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 382. ISBN 978-1-60547-433-5. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "definition of gravida". The Free Dictionary. Archived from the original on 29 October 2006. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ↑ "Gravidity and Parity Definitions (Implications in Risk Assessment)". patient.info. Archived from the original on 12 December 2016.

- ↑ Robinson, Victor, ed. (1939). "Primipara". The Modern Home Physician, A New Encyclopedia of Medical Knowledge. WM. H. Wise & Company (New York)., page 596.

- ↑ "Definition of nulligravida". Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ "Nulliparous definition". MedicineNet, Inc. 18 November 2000. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009.

- ↑ "Definition of Term Pregnancy - ACOG". www.acog.org. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ↑ "Definition of Premature birth". Medicine.net. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ↑ Lama Rimawi, MD (22 September 2006). "Premature Infant". Disease & Conditions Encyclopedia. Discovery Communications, LLC. Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ↑ Merck. "Urinary tract infections during pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Archived from the original on 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Vazquez JC (August 2010). "Constipation, haemorrhoids, and heartburn in pregnancy". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2010: 1411. PMC 3217736. PMID 21418682.

- ↑ MedlinePlus > Breast pain Archived 5 August 2012 at archive.today Update Date: 31 December 2008. Updated by: David C. Dugdale, Susan Storck. Also reviewed by David Zieve.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Obstetric Data Definitions Issues and Rationale for Change – Gestational Age & Term Archived 6 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine from Patient Safety and Quality Improvement at American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Created November 2012.

- ↑ Tunón K, Eik-Nes SH, Grøttum P, Von Düring V, Kahn JA (January 2000). "Gestational age in pregnancies conceived after in vitro fertilization: a comparison between age assessed from oocyte retrieval, crown-rump length and biparietal diameter". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 15 (1): 41–46. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00004.x. PMID 10776011.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 "Pregnancy - the three trimesters". University of California San Francisco. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Hoffman CS, Messer LC, Mendola P, Savitz DA, Herring AH, Hartmann KE (November 2008). "Comparison of gestational age at birth based on last menstrual period and ultrasound during the first trimester". Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 22 (6): 587–596. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00965.x. PMID 19000297.

- ↑ "Calculating Your Due Date". Healthline Networks, Inc. Archived from the original on 21 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2010.

- ↑ Chambliss LR, Clark SL (February 2014). "Paper gestational age wheels are generally inaccurate". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 210 (2): 145.e1–4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.09.013. PMID 24036402.

- ↑ Weschler, Toni (2002). Taking Charge of Your Fertility (Revised ed.). New York: HarperCollins. pp. 242, 374. ISBN 978-0-06-093764-5.

- ↑ Berger, Kathleen Stassen (2011). The Developing Person Through the Life Span. Macmillan. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-4292-3205-0. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016.

- ↑ "Stages of Development of the Fetus - Women's Health Issues". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1

- Lennart Nilsson, A Child is Born 91 (1990): at eight weeks, "the danger of a miscarriage ... diminishes sharply."

- "Women's Health Information Archived 30 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine", Hearthstone Communications Limited: "The risk of miscarriage decreases dramatically after the 8th week as the weeks go by." Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ↑ Kalverboer, Alex Fedde; Gramsbergen, Albertus Arend (1 January 2001). Handbook of Brain and Behaviour in Human Development. Springer. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-7923-6943-1. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015.

- ↑ Illes, Judy, ed. (2008). Neuroethics : defining the issues in theory, practice, and policy (Repr. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-19-856721-9. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015.

- ↑ "Abortion & Pregnancy Risks". Louisiana Department of Health. Archived from the original on 15 August 2019. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ↑ "Reproductive History and Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. 30 November 2016. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Mor, Gil, ed. (2006). Immunology of pregnancy. Medical intelligence unit. Georgetown, Tex. : New York: Landes Bioscience/Eurekah.com; Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 1–4. doi:10.1007/0-387-34944-8. ISBN 978-0-387-34944-2.

- ↑ Williams Z (September 2012). "Inducing tolerance to pregnancy". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (12): 1159–1161. doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr1207279. PMC 3644969. PMID 22992082.

- ↑ Campbell LA, Klocke RA (April 2001). "Implications for the pregnant patient". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 163 (5): 1051–1054. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.16353. PMID 11316633.

- ↑ "Your baby at 0–8 weeks pregnancy – Pregnancy and baby guide – NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. 20 December 2017. Archived from the original on 20 November 2013.

- ↑ Stacey T, Thompson JM, Mitchell EA, Ekeroma AJ, Zuccollo JM, McCowan LM (June 2011). "Association between maternal sleep practices and risk of late stillbirth: a case-control study". BMJ. 342: d3403. doi:10.1136/bmj.d3403. PMC 3114953. PMID 21673002.

- ↑ 48.00 48.01 48.02 48.03 48.04 48.05 48.06 48.07 48.08 48.09 48.10 48.11 Cunningham, F. Gary; Leveno, Kenneth J.; Bloom, Steven L.; Spong, Catherine Y.; Dashe, Jodi S.; Hoffman, Barbara L.; Casey, Brian M.; Sheffield, Jeanne S., eds. (2014). "Chapter 12. Teratology, Teratogens, and Fetotoxic Agents". Williams obstetrics (24th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Education. Archived from the original on 31 December 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ↑ "RHL". apps.who.int. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 World Health Organization (November 2013). "Preterm birth". who.int. Archived from the original on 7 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 51.4 51.5 51.6 51.7 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (22 October 2013). "Ob-Gyns Redefine Meaning of 'Term Pregnancy'". acog.org. Archived from the original on 15 September 2014. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ↑ Saigal S, Doyle LW (January 2008). "An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood". Lancet. 371 (9608): 261–269. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60136-1. PMID 18207020. S2CID 17256481.

- ↑ American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (February 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, archived from the original on 1 September 2013, retrieved 1 August 2013, which cites

- Main, Elliott; Oshiro, Bryan; Chagolla, Brenda; Bingham, Debra; Dang-Kilduff, Leona; Kowalewski, Leslie, Elimination of Non-medically Indicated (Elective) Deliveries Before 39 Weeks Gestational Age (PDF), March of Dimes; California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative; Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Division; Center for Family Health; California Department of Public Health, archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2012, retrieved 1 August 2013

- ↑ Michele Norris (18 July 2011). "Doctors To Pregnant Women: Wait At Least 39 Weeks". All Things Considered. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ↑ Norwitz, Errol R. "Postterm Pregnancy (Beyond the Basics)". UpToDate, Inc. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (April 2006). "What To Expect After Your Due Date". Medem. Medem, Inc. Archived from the original on 29 April 2003. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ↑ "Induction of labour – Evidence-based Clinical Guideline Number 9" (PDF). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ↑ Jenkins A, Millar S, Robins J (July 2011). "Denial of pregnancy: a literature review and discussion of ethical and legal issues". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 104 (7): 286–291. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2011.100376. PMC 3128877. PMID 21725094.

- ↑ Gabbe, Steven (1 January 2012). Obstetrics : normal and problem pregnancies (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 1184. ISBN 978-1-4377-1935-2.

- ↑ "Pregnancy Symptoms". National Health Service (NHS). 11 March 2010. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "Early symptoms of pregnancy: What happens right away". Mayo Clinic. 22 February 2007. Archived from the original on 14 September 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2007.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 "Pregnancy Symptoms – Early Signs of Pregnancy : American Pregnancy Association". Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2008.

- ↑ "Pregnancy video". Channel 4. 2008. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- ↑ "NHS Pregnancy Planner". National Health Service (NHS). 19 March 2010. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2010.

- ↑ Cole, Laurence A.; Butler, Stephen A., eds. (2015). Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-800821-8. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ↑ Qasim SM, Callan C, Choe JK (October 1996). "The predictive value of an initial serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin level for pregnancy outcome following in vitro fertilization". Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics. 13 (9): 705–708. doi:10.1007/BF02066422. PMID 8947817. S2CID 36218409.

- ↑ "BestBets: Serum or Urine beta-hCG?". Archived from the original on 31 December 2008.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Cole LA, Khanlian SA, Sutton JM, Davies S, Rayburn WF (January 2004). "Accuracy of home pregnancy tests at the time of missed menses". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 190 (1): 100–105. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2003.08.043. PMID 14749643.

- ↑ Verhaegen J, Gallos ID, van Mello NM, Abdel-Aziz M, Takwoingi Y, Harb H, Deeks JJ, Mol BW, Coomarasamy A (September 2012). "Accuracy of single progesterone test to predict early pregnancy outcome in women with pain or bleeding: meta-analysis of cohort studies". BMJ. 345: e6077. doi:10.1136/bmj.e6077. PMC 3460254. PMID 23045257.

- ↑ Whitworth M, Bricker L, Mullan C (July 2015). "Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD007058. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007058.pub3. PMC 4084925. PMID 26171896.

- ↑ Nguyen TH, Larsen T, Engholm G, Møller H (July 1999). "Evaluation of ultrasound-estimated date of delivery in 17,450 spontaneous singleton births: do we need to modify Naegele's rule?". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 14 (1): 23–28. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.1999.14010023.x. PMID 10461334.

- ↑ Pyeritz RE (2014). Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 2015. McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Waters TR, MacDonald LA, Hudock SD, Goddard DE (February 2014). "Provisional recommended weight limits for manual lifting during pregnancy". Human Factors. 56 (1): 203–214. doi:10.1177/0018720813502223. PMC 4606868. PMID 24669554. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017.

- ↑ MacDonald, Leslie A.; Waters, Thomas R.; Napolitano, Peter G.; Goddard, Donald E.; Ryan, Margaret A.; Nielsen, Peter; Hudock, Stephen D. (2013). "Clinical guidelines for occupational lifting in pregnancy: evidence summary and provisional recommendations". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 209 (2): 80–88. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.047. ISSN 0002-9378. PMC 4552317. PMID 23467051.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Lyons, Paul (2015). Obstetrics in family medicine: a practical guide. Current clinical practice (2nd ed.). Cham, Switzerland: Humana Press. pp. 19–28. ISBN 978-3-319-20077-4. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ↑ "WHO | Antenatal care". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ Dowswell T, Carroli G, Duley L, Gates S, Gülmezoglu AM, Khan-Neelofur D, Piaggio G, et al. (American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Undeserved Women) (July 2015). "Alternative versus standard packages of antenatal care for low-risk pregnancy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD000934. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000934.pub3. PMC 7061257. PMID 26184394.

- ↑ American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Undeserved Women (August 2006). "ACOG Committee Opinion No. 343: psychosocial risk factors: perinatal screening and intervention". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 108 (2): 469–77. doi:10.1097/00006250-200608000-00046. PMID 16880322.

- ↑ Hurt, K. Joseph, ed. (2011). The Johns Hopkins manual of gynecology and obstetrics (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4511-0913-9. Archived from the original on 13 April 2023. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ↑ McCormick, Marie C.; Siegel, Joanna E., eds. (1999). Prenatal care: effectiveness and implementation. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66196-6. Archived from the original on 6 November 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ↑ Zhang, C; Catalano, P (10 August 2021). "Screening for Gestational Diabetes". JAMA. 326 (6): 487–489. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.12190. PMID 34374733.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 Lammi-Keefe, Carol Jean; Couch, Sarah C.; Philipson, Elliot H., eds. (2008). Handbook of nutrition and pregnancy. Nutrition and health. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. p. 28. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-112-3. ISBN 978-1-59745-112-3.

- ↑ Ota E, Hori H, Mori R, Tobe-Gai R, Farrar D (June 2015). "Antenatal dietary education and supplementation to increase energy and protein intake". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD000032. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000032.pub3. PMID 26031211.

- ↑ "| Choose MyPlate". Choose MyPlate. 29 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ↑ Tieu, J; Sheperd, E; Middleton, P; Crowther, CA (3 January 2017). "Dietary advice interventions in pregnancy for preventing gestational diabetes mellitus". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD006674. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006674.pub3. PMC 6464792. PMID 28046205.

- ↑ Klusmann A, Heinrich B, Stöpler H, Gärtner J, Mayatepek E, Von Kries R (November 2005). "A decreasing rate of neural tube defects following the recommendations for periconceptional folic acid supplementation". Acta Paediatrica. 94 (11): 1538–1542. doi:10.1080/08035250500340396. PMID 16303691.

- ↑ Stevenson RE, Allen WP, Pai GS, Best R, Seaver LH, Dean J, Thompson S (October 2000). "Decline in prevalence of neural tube defects in a high-risk region of the United States". Pediatrics. 106 (4): 677–683. doi:10.1542/peds.106.4.677. PMID 11015508. S2CID 39696556.

- ↑ "Folic acid in diet: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". www.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (January 2008). "Use of supplements containing folic acid among women of childbearing age--United States, 2007". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (1): 5–8. PMID 18185493.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Guesnet P, Alessandri JM (January 2011). "Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and the developing central nervous system (CNS) – Implications for dietary recommendations". Biochimie. Bioactive Lipids, Nutrition and Health. 93 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2010.05.005. PMID 20478353.

- ↑ Salem N, Litman B, Kim HY, Gawrisch K (September 2001). "Mechanisms of action of docosahexaenoic acid in the nervous system". Lipids. 36 (9): 945–959. doi:10.1007/s11745-001-0805-6. PMID 11724467. S2CID 4052266. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ↑ Kawai K, Spiegelman D, Shankar AH, Fawzi WW (June 2011). "Maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation and pregnancy outcomes in developing countries: meta-analysis and meta-regression". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 89 (6): 402–411B. doi:10.2471/BLT.10.083758. PMC 3099554. PMID 21673856. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015.

- ↑ Canada, Public Health Agency of. "Folic acid, iron and pregnancy". www.canada.ca. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ↑ "Recommendations | Folic Acid | NCBDDD | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 21 August 2017. Archived from the original on 25 August 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ↑ Theobald HE (2007). "Eating for pregnancy and breast-feeding". The Journal of Family Health Care. 17 (2): 45–49. PMID 17476978.

- ↑ Basile LA, Taylor SN, Wagner CL, Quinones L, Hollis BW (September 2007). "Neonatal vitamin D status at birth at latitude 32 degrees 72': evidence of deficiency". Journal of Perinatology. 27 (9): 568–571. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211796. PMID 17625571. S2CID 23319012.

- ↑ Kuoppala T, Tuimala R, Parviainen M, Koskinen T, Ala-Houhala M (July 1986). "Serum levels of vitamin D metabolites, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium and alkaline phosphatase in Finnish women throughout pregnancy and in cord serum at delivery". Human Nutrition. Clinical Nutrition. 40 (4): 287–293. PMID 3488981.

- ↑ Rumbold, Alice; Ota, Erika; Hori, Hiroyuki; Miyazaki, Celine; Crowther, Caroline A (7 September 2015). "Vitamin E supplementation in pregnancy". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD004069. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004069.pub3. PMID 26343254.

- ↑ Ota, Erika; Mori, Rintaro; Middleton, Philippa; Tobe-Gai, Ruoyan; Mahomed, Kassam; Miyazaki, Celine; Bhutta, Zulfiqar A (2 February 2015). "Zinc supplementation for improving pregnancy and infant outcome". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD000230. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd000230.pub5. PMC 7043363. PMID 25927101.

- ↑ Peña-Rosas, Juan Pablo; De-Regil, Luz Maria; Garcia-Casal, Maria N; Dowswell, Therese (22 July 2015). "Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD004736. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004736.pub5. PMID 26198451.

- ↑ McDonagh M, Cantor A, Bougatsos C, Dana T, Blazina I (March 2015). "Routine Iron Supplementation and Screening for Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review to Update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation". Evidence Syntheses. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews (123). PMID 25927136. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ↑ "Nutritional Needs During Pregnancy". Choose MyPlate. 1 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ↑ "| Choose MyPlate". Choose MyPlate. 29 April 2015. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 CDC – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "Toxoplasmosis – General Information – Pregnant Women". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 18 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ↑ "Listeria and Pregnancy, Infections". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 Tam C, Erebara A, Einarson A (April 2010). "Food-borne illnesses during pregnancy: prevention and treatment". Canadian Family Physician. 56 (4): 341–343. PMC 2860824. PMID 20393091.

- ↑ Tarlow MJ (August 1994). "Epidemiology of neonatal infections". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 34 Suppl A: 43–52. doi:10.1093/jac/34.suppl_a.43. PMID 7844073.

- ↑ Jahanfar, Shayesteh; Jaafar, Sharifah Halimah (9 June 2015). "Effects of restricted caffeine intake by mother on fetal, neonatal and pregnancy outcomes". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD006965. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006965.pub4. PMID 26058966.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 109.2 Viswanathan M, Siega-Riz AM, Moos MK, et al. (May 2008). Outcomes of Maternal Weight Gain. Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 168. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PMID 18620471. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 110.2 Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. "Weight gain in pregnancy". Fact sheet. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ↑ "Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexaminging the Guidelines, Report Brief". Institute of Medicine. Archived from the original on 10 August 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- ↑ American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists (January 2013). "ACOG Committee opinion no. 548: weight gain during pregnancy". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 121 (1): 210–212. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000425668.87506.4c. PMID 23262962.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 Thangaratinam S, Rogozińska E, Jolly K, et al. (July 2012). Interventions to Reduce or Prevent Obesity in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. Health Technology Assessment, No. 16.31. Vol. 16. NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre. pp. iii–iv, 1–191. doi:10.3310/hta16310. PMC 4781281. PMID 22814301. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 114.2 Briggs, Gerald G.; Freeman, Roger K. (2015). Drugs in pregnancy and lactation: A Reference Guide to Fetal and Neonatal Risk (Tenth ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Health. p. Appendix. ISBN 978-1-4511-9082-3. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- ↑ Genetic Alliance; The New England Public Health Genetics Education Collaborative (17 February 2010). "Teratogens/Prenatal Substance Abuse". Genetic Alliance. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) Appendix A - ↑ "Press Announcements – FDA issues final rule on changes to pregnancy and lactation labeling information for prescription drug and biological products". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ↑ "Basics about FASDs". CDC. Archived from the original on 23 May 2015. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Hackshaw A, Rodeck C, Boniface S (September–October 2011). "Maternal smoking in pregnancy and birth defects: a systematic review based on 173 687 malformed cases and 11.7 million controls". Human Reproduction Update. 17 (5): 589–604. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr022. PMC 3156888. PMID 21747128.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007. Preventing Smoking and Exposure to Secondhand Smoke Before, During, and After Pregnancy Archived 11 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Tobacco Use and Pregnancy – Reproductive Health". www.cdc.gov. 16 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 "New Mother Fact Sheet: Methamphetamine Use During Pregnancy". North Dakota Department of Health. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.