Temazepam

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

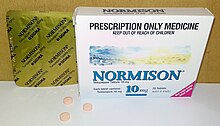

| Trade names | Restoril, Normison, Nortem, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Dependence risk | High[2] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 20 mg[1] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684003 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 96% |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 8–20 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C16H13ClN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 300.74 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Temazepam, sold under the brand names Restoril among others, is a medication used to treat trouble sleeping.[3] Such use should generally be for less than ten days.[3] It is taken by mouth.[3] Effects generally begin within an hour and last for up to eight hours.[4]

Common side effects include sleepiness, anxiety, confusion, and dizziness.[3] Serious side effects may include hallucinations, abuse, anaphylaxis, and suicide.[3] Use is generally not recommended together with opioids.[3] If the dose is rapidly decreased withdrawal may occur.[3] Use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is not recommended.[5] Temazepam is an intermediate acting benzodiazepine and hypnotic.[3][4] It works by affecting GABA within the brain.[3]

Temazapam was patented in 1962 and came into medical use in 1969.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[7] A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £1.40 as of 2019.[7] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$1.76.[8] In 2017, it was the 142nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than four million prescriptions.[9][10]

Medical uses

In sleep laboratory studies, temazepam significantly decreased the number of nightly awakenings,[11] but has the drawback of distorting the normal sleep pattern.[12] It is officially indicated for severe insomnia and other severe or disabling sleep disorders. The prescribing guidelines in the UK limit the prescribing of hypnotics to two to four weeks due to concerns of tolerance and dependence.[13]

The United States Air Force uses temazepam as one of the hypnotics approved as a "no-go pill" to help aviators and special-duty personnel sleep in support of mission readiness. "Ground tests" are necessary prior to required authorization being issued to use the medication in an operational situation, and a 12-hour restriction is imposed on subsequent flight operation.[14] The other hypnotics used as "no-go pills" are zaleplon and zolpidem, which have shorter mandatory recovery periods.[14]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 20 mg by mouth.[1]

Side effects

Common

Side effects typical of hypnotic benzodiazepines are related to CNS depression, and include somnolence, sedation, drunkenness, dizziness, fatigue, ataxia, headache, lethargy, impairment of memory and learning, longer reaction time and impairment of motor functions (including coordination problems),[15] slurred speech, decreased physical performance, numbed emotions, reduced alertness, muscle weakness, blurred vision (in higher doses), and inattention. Euphoria was rarely reported with its use. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, temazepam had an incidence of euphoria of 1.5%, much more rarely reported than headaches and diarrhea.[16] Anterograde amnesia may also develop, as may respiratory depression in higher doses.

A 2009 meta-analysis found a 44% higher rate of mild infections, such as pharyngitis or sinusitis, in people taking Temazepam or other hypnotic drugs compared to those taking a placebo.[17]

Less common

Hyperhydrosis, hypotension, burning eyes, increased appetite, changes in libido, hallucinations, faintness, nystagmus, vomiting, pruritus, gastrointestinal disturbances, nightmares, palpitation and paradoxical reactions including restlessness, aggression, violence, overstimulation and agitation have been reported, but are rare (less than 0.5%).

Before taking temazepam, one should ensure that at least 8 hours are available to dedicate to sleep. Failing to do so can increase the side effects of the drug.

Like all benzodiazepines, the use of this drug in combination with alcohol potentiates the side effects, and can lead to toxicity and death.

Though rare, residual "hangover" effects after night-time administration of temazepam occasionally occur. These include sleepiness, impaired psychomotor and cognitive functions which may persist into the next day, impaired driving ability, and possible increased risks of falls and hip fractures, especially in the elderly.[18]

Contraindications

Use of temazepam should be avoided, when possible, in individuals with these conditions:

- Ataxia (gross lack of coordination of muscle movements)

- Severe hypoventilation

- Acute narrow-angle glaucoma

- Severe liver deficiencies (hepatitis and liver cirrhosis decrease elimination by a factor of two)

- Severe renal deficiencies (e.g. patients on dialysis)

- Sleep apnea[19]

- Severe depression, particularly when accompanied by suicidal tendencies

- Acute intoxication with alcohol, narcotics, or other psychoactive substances

- Myasthenia gravis (autoimmune disorder causing muscle weakness)

- Hypersensitivity or allergy to any drug in the benzodiazepine class

Cautions

Temazepam should not be used in pregnancy, as it may cause harm to the baby. The safety and effectiveness of temazepam has not been established in children; therefore, temazepam should generally not be given to individuals under 18 years of age, and should not be used at all in children under six months old. Benzodiazepines also require special caution if used in the elderly, alcohol- or drug-dependent individuals, and individuals with comorbid psychiatric disorders.[20]

Temazepam, similar to other benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic drugs, causes impairments in body balance and standing steadiness in individuals who wake up at night or the next morning. Falls and hip fractures are frequently reported. The combination with alcohol increases these impairments. Partial but incomplete tolerance develops to these impairments.[21] The smallest possible effective dose should be used in elderly or very ill patients, as a risk of apnea and/or cardiac arrest exists. This risk is increased when temazepam is given concomitantly with other drugs that depress the central nervous system (CNS).[16]

Misuse and dependence

Because benzodiazepines can be abused and lead to dependence, their use should be avoided in people in certain particularly high-risk groups. These groups include people with a history of alcohol or drug dependence, people significantly struggling with their mood or people with longstanding mental health difficulties. If temazepam must be prescribed to people in these groups, they should generally be monitored very closely for signs of misuse and development of dependence.[13]

Tolerance

Chronic or excessive use of temazepam may cause drug tolerance, which can develop rapidly,[22] so this drug is not recommended for long-term use.[16][23] In 1979, the Institute of Medicine (USA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse stated that most hypnotics lose their sleep-inducing properties after about three to 14 days.[24] In use longer than one to two weeks, tolerance will rapidly develop towards the ability of temazepam to maintain sleep, resulting in a loss of effectiveness.[25] Some studies have observed tolerance to temazepam after as little as one week's use.[26] Another study examined the short-term effects of the accumulation of temazepam over seven days in elderly inpatients, and found little tolerance developed during the accumulation of the drug.[27] Other studies examined the use of temazepam over six days and saw no evidence of tolerance.[28][29] A study in 11 young male subjects showed significant tolerance occurs to temazepam's thermoregulatory effects and sleep inducing properties after one week of use of 30-mg temazepam. Body temperature is well correlated with the sleep-inducing or insomnia-promoting properties of drugs.[30]

In one study, the drug sensitivity of people who had used temazepam for one to 20 years was no different from that of controls.[31] An additional study, in which at least one of the authors is employed by multiple drug companies, examined the efficacy of temazepam treatment on chronic insomnia over three months, and saw no drug tolerance, with the authors even suggesting the drug might become more effective over time.[32][33][34]

Establishing continued efficacy beyond a few weeks can be complicated by the difficulty in distinguishing between the return of the original insomnia complaint and withdrawal or rebound related insomnia. Sleep EEG studies on hypnotic benzodiazepines show tolerance tends to occur completely after one to four weeks with sleep EEG returning to pretreatment levels. The paper concluded that due to concerns about long-term use involving toxicity, tolerance and dependence, as well as to controversy over long-term efficacy, wise prescribers should restrict benzodiazepines to a few weeks and avoid continuing prescriptions for months or years.[35] A review of the literature found the nonpharmacological treatment options were a more effective treatment option for insomnia due to their sustained improvements in sleep quality.[36]

Physical dependence

Temazepam, like other benzodiazepine drugs, can cause physical dependence and addiction. Withdrawal from temazepam or other benzodiazepines after regular use often leads to benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, which resembles symptoms during alcohol and barbiturate withdrawal. The higher the dose and the longer the drug is taken, the greater the risk of experiencing unpleasant withdrawal symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms can also occur from standard dosages and after short-term use. Abrupt withdrawal from therapeutic doses of temazepam after long-term use may result in a severe benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome. Gradual and careful reduction of the dosage, preferably with a long-acting benzodiazepine with long half-life active metabolites, such as chlordiazepoxide or diazepam, are recommended to prevent severe withdrawal syndromes from developing. Other hypnotic benzodiazepines are not recommended.[37] A study in rats found temazepam is cross tolerant with barbiturates and is able to effectively substitute for barbiturates and suppress barbiturate withdrawal signs.[38] Rare cases are reported in the medical literature of psychotic states developing after abrupt withdrawal from benzodiazepines, even from therapeutic doses.[39] Antipsychotics increase the severity of benzodiazepine withdrawal effects with an increase in the intensity and severity of convulsions.[40] Patients who were treated in the hospital with temazepam or nitrazepam have continued taking these after leaving the hospital. Hypnotic uses in the hospital were recommended to be limited to five nights' use only, to avoid the development of withdrawal symptoms such as insomnia.[41]

Interactions

As with other benzodiazepines, temazepam produces additive CNS-depressant effects when coadministered with other medications which themselves produce CNS depression, such as barbiturates, alcohol,[42] opiates, tricyclic antidepressants, nonselective MAO inhibitors, phenothiazines and other antipsychotics, skeletal muscle relaxants, antihistamines, and anaesthetics. Administration of theophylline or aminophylline has been shown to reduce the sedative effects of temazepam and other benzodiazepines.

Unlike many benzodiazepines, pharmacokinetic interactions involving the P450 system have not been observed with temazepam. Temazepam shows no significant interaction with CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g. itraconazole, erythromycin).[43] Oral contraceptives may decrease the effectiveness of temazepam and speed up its elimination half-life.[44]

Overdose

Overdosage of temazepam results in increasing CNS effects, including:

- Somnolence (difficulty staying awake)

- Mental confusion

- Respiratory depression

- Hypotension

- Impaired motor functions

- Impaired or absent reflexes

- Impaired coordination

- Impaired balance

- Dizziness, sedation

- Coma

- Death

Temazepam had the highest rate of drug intoxication, including overdose, among common benzodiazepines in cases with and without combination with alcohol in a 1985 study.[45] Temazepam and nitrazepam were the two benzodiazepines most commonly detected in overdose-related deaths in an Australian study of drug deaths.[46] A 1993 British study found temazepam to have the highest number of deaths per million prescriptions among medications commonly prescribed in the 1980s (11.9, versus 5.9 for benzodiazepines overall, taken with or without alcohol).[47]

A 1995 Australian study of patients admitted to hospital after benzodiazepine overdose corroborated these results, and found temazepam overdose much more likely to lead to coma than other benzodiazepines (odds ratio 1.86). The authors noted several factors, such as differences in potency, receptor affinity, and rate of absorption between benzodiazepines, could explain this higher toxicity.[45] Although benzodiazepines have a high therapeutic index, temazepam is one of the more dangerous of this class of drugs. The combination of alcohol and temazepam makes death by alcohol poisoning more likely.[48]

Pharmacology

Temazepam is a white, crystalline substance, very slightly soluble in water, and sparingly soluble in alcohol. Its main pharmacological action is to increase the effect of the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) at the GABAA receptor. This causes sedation, motor impairment, ataxia, anxiolysis, an anticonvulsant effect, muscle relaxation, and a reinforcing effect.[49] As a medication before surgery, temazepam decreased cortisol in elderly patients.[50] In rats, it triggered the release of vasopressin into paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and decreased the release of ACTH under stress.[51]

Pharmacokinetics

Oral administration of 15 to 45 mg of temazepam in humans resulted in rapid absorption with significant blood levels achieved in fewer than 30 minutes and peak levels at two to three hours.[52] In a single- and multiple-dose absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) study, using tritium-labelled drug, temazepam was well absorbed and found to have minimal (8%) first-pass drug metabolism. No active metabolites were formed and the only significant metabolite present in blood was the O-conjugate. The unchanged drug was 96% bound to plasma proteins. The blood-level decline of the parent drug was biphasic, with the short half-life ranging from 0.4-0.6 hours and the terminal half-life from 3.5–18.4 hours (mean 8.8 hours), depending on the study population and method of determination.[53]

Temazepam has very good bioavailability, with almost 100% being absorbed following being taken by mouth. The drug is metabolized through conjugation and demethylation prior to excretion. Most of the drug is excreted in the urine, with about 20% appearing in the faeces. The major metabolite was the O-conjugate of temazepam (90%); the O-conjugate of N-desmethyl temazepam was a minor metabolite (7%).[54]

History

Temazepam was synthesized in 1964, but it came into use in 1981 when its ability to counter insomnia was realized.[55] By the late 1980s, temazepam was one of the most popular and widely prescribed[citation needed] hypnotics on the market and it became one of the most widely prescribed drugs.

Society and culture

Recreational use

Temazepam is a drug with a high potential for misuse.[56]

Benzodiazepines have been abused orally and intravenously. Different benzodiazepines have different abuse potential; the more rapid the increase in the plasma level following ingestion, the greater the intoxicating effect and the more open to abuse the drug becomes. The speed of onset of action of a particular benzodiazepine correlates well with the ‘popularity’ of that drug for abuse. The two most common reasons for preference were that a benzodiazepine was ‘strong’ and that it gave a good ‘high’.[57]

A 1995 study found that temazepam is more rapidly absorbed and oxazepam is more slowly absorbed than most other benzodiazepines.[58]

A 1985 study found that temazepam and triazolam maintained significantly higher rates of self-injection than a variety of other benzodiazepines. The study tested and compared the abuse liability of temazepam, triazolam, diazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, flurazepam, alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, nitrazepam, flunitrazepam, bromazepam, and clorazepate. The study tested self-injection rates on human, baboon, and rat subjects. All test subjects consistently showed a strong preference for temazepam and triazolam over all the rest of the benzodiazepines included in the study.[59]

North America

In North America, temazepam misuse is not widespread. Other benzodiazepines are more commonly prescribed for insomnia. In the United States, temazepam is the fifth-most prescribed benzodiazepine, however there is a major drop off from the top four most prescribed (alprazolam, lorazepam, diazepam, and clonazepam in that order). Individuals abusing benzodiazepines obtain the drug by getting prescriptions from several doctors, forging prescriptions, or buying diverted pharmaceutical products on the illicit market.[60] North America has never had a serious problem with temazepam misuse, but is becoming increasingly vulnerable to the illicit trade of temazepam.[61]

Australia

Temazepam is a Schedule 4 drug and requires a prescription. The drug accounts for most benzodiazepine sought by forgery of prescriptions and through pharmacy burglary in Victoria.[62] Due to rife intravenous abuse, the Australian government decided to put it under a more restrictive schedule than it had been,[63] and since March 2004 temazepam capsules have been withdrawn from the Australian market, leaving only 10 mg tablets available.[64][65] Benzodiazepines are commonly detected by Customs at different ports and airports, arriving by mail, also found occasionally in the baggage of air passengers, mostly small or medium quantities (up to 200–300 tablets) for personal use. From 2003 to 2006, customs detected about 500 illegal importations of benzodiazepines per year, most frequently diazepam. Quantities varied from single tablets to 2,000 tablets.[66][67]

United Kingdom

In 1987, temazepam was the most widely abused legal prescription drug in the United Kingdom. The use of benzodiazepines by street-drug abusers was part of a polydrug abuse pattern, but many of those entering treatment facilities were declaring temazepam as their main drug of abuse. Temazepam was the most commonly used benzodiazepine in a study, published 1994, of injecting drug users in seven cities, and had been injected from preparations of capsules, tablets, and syrup.[68] The increase in use of heroin, often mixed with other drugs, which most often included temazepam, diazepam, and alcohol, was a major factor in the increase in drug-related deaths in Glasgow and Edinburgh in 1990–1992.[69] Temazepam use was particularly associated with violent or disorderly behaviours and contact with the police in a 1997 study of young single homeless people in Scotland.[70] The BBC series Panorama featured an episode titled "Temazepam Wars", dealing with the epidemic of temazepam abuse and directly related crime in Paisley, Scotland.

Medical research issues

The Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine published a paper expressing concerns about benzodiazepine receptor agonist drugs, the benzodiazepines and the Z-drugs used as hypnotics in humans. The paper cites a systematic review of the medical literature concerning insomnia medications and states almost all trials of sleep disorders and drugs are sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, while this is not the case in general medicine or psychiatry. It cites another study that "found that the odds ratio for finding results favorable to industry in industry-sponsored trials was 3.6 times as high as in non–industry-sponsored studies". Issues discussed regarding industry-sponsored studies include: comparison of a drug to a placebo, but not to an alternative treatment; unpublished studies with unfavorable outcomes; and trials organized around a placebo baseline followed by drug treatment, but not counterbalanced with parallel-placebo-controlled studies. Quoting a 1979 report that too little research into hypnotics was independent of the drug manufacturers, the authors conclude, "the public desperately needs an equipoised assessment of hypnotic benefits and risks" and the NIH and VA should provide leadership to that end.[71]

Street terms

Street terms for temazepam include king kong pills (formerly referred to barbiturates, now more commonly refers to temazepam), jellies, jelly, Edinburgh eccies, tams, terms, mazzies, temazies, tammies, temmies, beans, eggs, green eggs, wobbly eggs, knockouts, hardball, norries, oranges (common term in Australia and New Zealand), rugby balls, ruggers, terminators, red and blue, no-gos, num nums, blackout, green devils, drunk pills, brainwash, mind erasers, neurotrashers, tem-tem's (combined with buprenorphine), mommy's big helper, vitamin T, big T, TZ, The Mazepam, Resties (North America) and others.[72][73]

Availability

Temazepam is available in English-speaking countries under the following brand names:

- Euhypnos

- Normison

- Norkotral

- Nortem

- Remestan

- Restoril

- Temaze

- Temtabs

- Tenox

In Spain, the drug is sold as 'temzpem'. In Hungary the drug is sold as Signopam.

Legal status

In Austria, temazepam is listed in UN71 Schedule III under the Psychotropic Substances Decree of 1997. The drug is considered to have a high potential for abuse and addiction, but has accepted medical use for the treatment of severe insomnia.[74]

In Australia, temazepam is a Schedule 4 - Prescription Only medicine.[75] It is primarily used for the treatment of insomnia, and is also seen as pre-anaesthetic medication.[76]

In Canada, temazepam is a Schedule IV controlled substance requiring a registered doctor's prescription.[77]

In Denmark, temazepam is listed as a Class D substance under the Executive Order 698 of 1993 on Euphoric Substances which means it has a high potential for abuse, but is used for medical and scientific purposes.[78]

In Finland, temazepam is more tightly controlled than other benzodiazepines. The temazepam product Normison was pulled out of shelves and banned because the liquid inside gelatin capsules had caused a large increase in intravenous temazepam use. The other temazepam product, Tenox, was not affected and remains as prescription medicine. Temazepam intravenous use has not decreased to the level before Normison came to the market.[74]

In France, temazepam is listed as a psychotropic substance as are other similar drugs. It is prescribed with a nonrenewable prescription (a new doctor visit every time), available only in 7 or 14-pill packaging for one or two weeks.[74] One brand was withdrawn from the market in 2013.[79]

In Hong Kong, temazepam is regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. Temazepam can only be used legally by health professionals and for university research purposes. The substance can be given by pharmacists under a prescription. Anyone who supplies the substance without prescription can be fined HKD$10,000. The penalty for trafficking or manufacturing the substance is a $5,000,000-fine and life imprisonment. Possession of the substance for consumption without license from the Department of Health is illegal with a $1,000,000-fine and/or seven years of jail time.[80]

In Ireland, temazepam is a Schedule 3 controlled substance with strict restrictions.[81]

In the Netherlands, temazepam is available for prescription as 10- or 20-mg tablets and capsules. Formulations of temazepam containing less than 20 mg are included in List 2 of the Opium Law, while formulations containing 20 mg or more of the drug (along with the gel-capsules) are a List 1 substance of the Opium Law, thus subject to more stringent regulation. Besides being used for insomnia, it is also occasionally used as a preanesthetic medication.[74]

In Norway, temazepam is not available as a prescription drug. It is regulated as a Class A substance under Norway's Narcotics Act.[74]

In Portugal, temazepam is a Schedule IV controlled drug under Decree-Law 15/93.[82]

In Singapore, temazepam is a Class A controlled drug (Schedule I), making it illegal to possess and requiring a private prescription from a licensed physician to be dispensed.

In Slovenia, it is regulated as a Group II (Schedule 2) controlled substance under the Production and Trade in Illicit Drugs Act.[74]

In South Africa, temazepam is a Schedule 5 drug, requiring a special prescription, and is restricted to 10– to 30-mg doses.[83]

In Sweden, temazepam is classed as a "narcotic" drug listed as both a List II (Schedule II) which denotes it is a drug with limited medicinal use and a high risk of addiction, and is also listed as a List V (Schedule V) substance which denotes the drug is prohibited in Sweden under the Narcotics Drugs Act (1968).[84] Temazepam is banned in Sweden and possession and distribution of even small amounts is punishable by a prison sentence and a fine.[74]

In Switzerland, temazepam is a Class B controlled substance, like all other benzodiazepines. This means it is a prescription-only drug.[85]

In Thailand, temazepam is a Schedule II controlled drug under the Psychotropic Substances Act. Possession and distribution of the drug is illegal.

In the United Kingdom, temazepam is a Class C controlled drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Schedule 3 under the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001).[86][87] If prescribed privately (not on the NHS), temazepam is available only by a special controlled drug prescription form (FP10PCD) and pharmacies are obligated to follow special procedures for storage and dispensing.[88] Additionally, all manufacturers in the UK have replaced the gel-capsules with solid tablets. Temazepam requires safe custody and up until June 2015 was exempt from CD prescription requirements.

In the United States, Temazepam is currently a Schedule IV drug under the international Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 and is only available by prescription. Specially coded prescriptions may be required in certain states.[89]

Cost

A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS about £1.40 as of 2019.[7] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$1.76.[8] In 2017, it was the 142nd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than four million prescriptions.[9][10]

-

Temazepam costs (US)

-

Temazepam prescriptions (US)

Synthesis

Pharmacologically active metabolite of diazepam, q.v.

N-oxides are prone to undergo the Polonovski rearrangement when treated with acetic anhydride, and this was illustrated by the synthesis of oxazepam. It is not surprising that the N-methyl analogue (1) also undergoes this process, and hydrolysis of the resulting acetate gives temazepam (2). Care must be exacted with the conditions, or the inactive rearrangement product (3) results.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ↑ "Temazepam". www.drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 "Temazepam Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Collins, Shelly Rainforth; RN-BC, Shelly Rainforth Collins (2015). Pharmacology and the Nursing Process. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 193. ISBN 9780323358286. Archived from the original on 2020-01-04. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ↑ "Temazepam (Restoril) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 537. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2020-01-02. Retrieved 2019-03-02.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 British national formulary: BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 481. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Temazepam - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ Bixler EO, Kales A, Soldatos CR, Scharf MB, Kales JD (1978). "Effectiveness of temazepam with short-intermediate-, and long-term use: sleep laboratory evaluation". J Clin Pharmacol. 18 (2–3): 110–8. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1978.tb02430.x. PMID 342551.

The effectiveness of 30 mg temazepam (SaH 47-603) for inducing and maintaining sleep was evaluated in the sleep laboratory in six insomniac subjects....

[permanent dead link] - ↑ Ferrillo, F; Balestra, V; Carta, F; Nuvoli, G; Pintus, C; Rosadini, G (1984). "Comparison between the central effects of camazepam and temazepam. Computerized analysis of sleep recordings". Neuropsychobiology. 11 (1): 72–6. doi:10.1159/000118055. PMID 6146112.

The effects of acute administration per os of 30 mg camazepam and the same dose of temazepam, were compared with placebo in 8 young male volunteers....

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 BNF (2008). "TEMAZEPAM". British National Formulary. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Caldwell, J. A.; Caldwell, J. L. (July 2005). "Fatigue in Military Aviation: An Overview of US Military-Approved Pharmacological Countermeasures" (pdf). Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 76 (Supplement 1): C39–C51. PMID 16018329. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-05-24. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- ↑ Liljequist, R.; Mattila, M. J. (May 1979). "Acute effects of temazepam and nitrazepam on psychomotor skills and memory". Acta Pharmacologica et Toxicologica. 44 (5): 364–369. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0773.1979.tb02346.x. PMC 1429620. PMID 38627.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Temazepam". Drugs.com. October 2007. Archived from the original on 2019-08-29. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- ↑ Joya, FL; Kripke, DF; Loving, RT; Dawson, A; Kline, LE (2009). "Meta-Analyses of Hypnotics and Infections: Eszopiclone, Ramelteon, Zaleplon, and Zolpidem". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 5 (4): 377–383. doi:10.5664/jcsm.27552. PMC 2725260. PMID 19968019.

- ↑ Vermeeren, A. (2004). "Residual effects of hypnotics: epidemiology and clinical implications". CNS Drugs. 18 (5): 297–328. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418050-00003. PMID 15089115.

- ↑ "Temazepam Oral". Web MD Professional. Medscape. Archived from the original on 2019-12-30. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ Authier, N.; Balayssac, D.; Sautereau, M.; Zangarelli, A.; Courty, P.; Somogyi, A. A.; Vennat, B.; Llorca, P.-M.; Eschalier, A. (November 2009). "Benzodiazepine dependence: Focus on withdrawal syndrome". Annales Pharmaceutiques Françaises. 67 (6): 408–413. doi:10.1016/j.pharma.2009.07.001. PMID 19900604.

- ↑ Mets, M. A.; Volkerts, E. R.; Olivier, B.; Verster, J. C. (February 2010). "Effect of hypnotic drugs on body balance and standing steadiness". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 14 (4): 259–267. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.008. PMID 20171127.

- ↑ Kales, A. (1990). "Quazepam: hypnotic efficacy and side effects". Pharmacotherapy. 10 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1990.tb02545.x (inactive 2020-03-05). PMID 1969151.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2020 (link) - ↑ "Temazepam: MedlinePlus Drug Information". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-01-03. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- ↑ "Systematic review of the benzodiazepines. Guidelines for data sheets on diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, medazepam, clorazepate, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, triazolam, nitrazepam, and flurazepam. Committee on the Review of Medicines". Br Med J. 280 (6218): 910–2. March 1980. doi:10.1136/bmj.280.6218.910. PMC 1601049. PMID 7388368.

- ↑ Kales A, Bixler EO, Soldatos CR, Vela-Bueno A, Jacoby JA, Kales JD (March 1986). "Quazepam and temazepam: effects of short- and intermediate-term use and withdrawal". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 39 (3): 345–52. doi:10.1038/clpt.1986.51. PMID 2868823.

- ↑ Roehrs T, Kribbs N, Zorick F, Roth T (1982). "Hypnotic residual effects of benzodiazepines with repeated administration". Sleep. 9 (2): 309–16. doi:10.1093/sleep/9.2.309. PMID 2905824.

- ↑ Cook PJ; Huggett A; Graham-Pole R; Savage IT; James IM (8 January 1983). "Hypnotic accumulation and hangover in elderly inpatients: a controlled double-blind study of temazepam and nitrazepam". Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 286 (6359): 100–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.286.6359.100. PMC 1546430. PMID 6129914.

- ↑ Griffiths AN; Tedeschi G; Richens A (1986). "The effects of repeated doses of temazepam and nitrazepam on several measures of human performance". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplementum. 332: 119–26. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1986.tb08988.x. PMID 2883819.

- ↑ Tedeschi G, Griffiths AN, Smith AT, Richens A (1 October 1985). "The effect of repeated doses of temazepam and nitrazepam on human psychomotor performance". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 20 (4): 361–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1985.tb05078.x. PMC 1400899. PMID 2866784.

- ↑ Gilbert SS; Burgess HJ; Kennaway DJ; Dawson D (1 December 2000). "Attenuation of sleep propensity, core hypothermia, and peripheral heat loss after temazepam tolerance". Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 279 (6): R1980–7. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R1980. PMID 11080060. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ↑ van Steveninck AL, Wallnöfer AE, Schoemaker RC, et al. (September 1997). "A study of the effects of long-term use on individual sensitivity to temazepam and lorazepam in a clinical population". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 44 (3): 267–75. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.t01-1-00580.x. PMC 2042835. PMID 9296321.

- ↑ Allen RP, Mendels J, Nevins DB, Chernik DA, Hoddes E (October 1987). "Efficacy without tolerance or rebound insomnia for midazolam and temazepam after use for one to three months". J Clin Pharmacol. 27 (10): 768–75. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1987.tb02994.x. PMID 2892863.

- ↑ "Conflict of interest disclosures" (PDF). American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the Sleep Research Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ↑ Richard P. Allen; Wayne A. Hening (March 2005). "Management of Restless Legs Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- ↑ Lader MH (December 1999). "Limitations on the use of benzodiazepines in anxiety and insomnia: are they justified?". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 9 Suppl 6: S399–405. doi:10.1016/S0924-977X(99)00051-6. PMID 10622686.

- ↑ Kirkwood CK (1999). "Management of insomnia". J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 39 (5): 688–96, quiz 713–4. doi:10.1016/S1086-5802(15)30354-5. PMID 10533351.

- ↑ MacKinnon GL; Parker WA (1982). "Benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome: a literature review and evaluation". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 9 (1): 19–33. doi:10.3109/00952998209002608. PMID 6133446.

- ↑ Yutrzenka GJ, Patrick GA, Rosenberger W (July 1989). "Substitution of temazepam and midazolam in pentobarbital-dependent rats". Physiol. Behav. 46 (1): 55–60. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(89)90321-1. PMID 2573097.

- ↑ Terao T, Tani Y (1988). "[Two cases of psychotic state following normal-dose benzodiazepine withdrawal]". J. UOEH (in Japanese). 10 (3): 337–40. doi:10.7888/juoeh.10.337. PMID 2902678.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ Tagashira E, Hiramori T, Urano T, Nakao K, Yanaura S (1981). "Enhancement of drug withdrawal convulsion by combinations of phenobarbital and antipsychotic agents". Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 31 (5): 689–99. doi:10.1254/jjp.31.689. PMID 6118452.

- ↑ Hecker R; Burr M; Newbury G (1992). "Risk of benzodiazepine dependence resulting from hospital admission". Drug Alcohol Rev. 11 (2): 131–5. doi:10.1080/09595239200185601. PMID 16840267.

- ↑ Liljequist R; Palva E; Linnoila M (1979). "Effects on learning and memory of 2-week treatments with chlordiazepoxide lactam, N-desmethyldiazepam, oxazepam and methyloxazepam, alone or in combination with alcohol". Int Pharmacopsychiatry. 14 (4): 190–8. doi:10.1159/000468381. PMID 42628.

- ↑ Ahonen J, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ (1996). "Lack of effect of antimycotic itraconazole on the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of temazepam". Ther Drug Monit. 18 (2): 124–7. doi:10.1097/00007691-199604000-00003. PMID 8721273.

- ↑ Stoehr GP, Kroboth PD, Juhl RP, Wender DB, Phillips JP, Smith RB (November 1984). "Effect of oral contraceptives on triazolam, temazepam, alprazolam, and lorazepam kinetics". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 36 (5): 683–90. doi:10.1038/clpt.1984.240. PMID 6149030.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Buckley N. A.; Dawson, A. H.; Whyte, I. M.; O'Connell, D. L. (1995). "Relative toxicity of benzodiazepines in overdose". BMJ. 310 (6974): 219–221. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6974.219. PMC 2548618. PMID 7866122. Archived from the original on 2010-01-13. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ↑ Drummer OH; Ranson DL (December 1996). "Sudden death and benzodiazepines". Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 17 (4): 336–42. doi:10.1097/00000433-199612000-00012. PMID 8947361.

- ↑ Serfaty M, Masterton G (1993). "Fatal poisonings attributed to benzodiazepines in Britain during the 1980s". Br J Psychiatry. 163 (3): 386–93. doi:10.1192/bjp.163.3.386. PMID 8104653. Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2020-01-10.

- ↑ Koski A, Ojanperä I, Vuori E (May 2003). "Interaction of alcohol and drugs in fatal poisonings". Hum Exp Toxicol. 22 (5): 281–7. doi:10.1191/0960327103ht324oa. PMID 12774892.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Oelschläger H (July 4, 1989). "[Chemical and pharmacologic aspects of benzodiazepines]". Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 78 (27–28): 766–72. PMID 2570451.

- ↑ Salonen M, Kanto J, Hovi-Viander M, Irjala K, Viinamäki O (November 1986). "Oral temazepam as a premedicant in elderly general surgical patients". Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 30 (8): 689–92. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.1986.tb02503.x. PMID 2880447.

- ↑ Welt T, Engelmann M, Renner U, et al. (2006). "Temazepam triggers the release of vasopressin into the rat hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: novel insight into benzodiazepine action on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system activity during stress". Neuropsychopharmacology. 31 (12): 2573–9. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301006. PMID 16395302.

- ↑ "RESTORIL® Novartis Temazepam Hypnotic". Pharmaceutical Information. RxMed. Archived from the original on 2008-10-18. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ↑ Müller FO, Van Dyk M, Hundt HK, et al. (1987). "Pharmacokinetics of temazepam after day-time and night-time oral administration". Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 33 (2): 211–4. doi:10.1007/BF00544571. PMID 2891534.

- ↑ Schwarz HJ (August 1, 1979). "Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of temazepam in man and several animal species". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 8 (1): 23S–29S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb00451.x. PMC 1429628. PMID 41539.

- ↑ Maggini C; Murri M; Sacchetti G (October 1969). "Evaluation of the effectiveness of temazepam on the insomnia of patients with neurosis and endogenous depression". Arzneimittelforschung. 19 (10): 1647–52. PMID 4311716.

- ↑ Griffiths RR, Johnson MW (2005). "Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds". J Clin Psychiatry. 66 Suppl 9: 31–41. PMID 16336040.

- ↑ Australian Government; Medical Board (2006). "ACT MEDICAL BOARD – STANDARDS STATEMENT – PRESCRIBING OF BENZODIAZEPINES" (PDF). Australia: ACT medical board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- ↑ Buckley, N. A.; Dawson, A. H.; Whyte, I. M.; O'Connell, D. L. (1995). "Relative toxicity of benzodiazepines in overdose". British Medical Journal. 310 (6974): 219–21. doi:10.1136/bmj.310.6974.219. PMC 2548618. PMID 7866122. Archived from the original on 2020-01-26. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ↑ GRIFFITHS, Roland R.; RICHARD J. LAMB; NANCY A. ATOR; JOHN D. ROACHE; JOSEPH V. BRADY (1985). "Relative Abuse Liability of Triazolam: Experimental Assessment in Animals and Humans" (PDF). Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 9 (1): 133–151. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.410.6027. doi:10.1016/0149-7634(85)90039-9. PMID 2858078. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ↑ "DEA Diversion Control Division". www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-01-03. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- ↑ Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (BINLEA), 2006.

- ↑ "Injecting Temazepam: The facts — Temazepam Injection and Diversion". Victorian Government Health Information. 29 March 2007. Archived from the original on 7 January 2008. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- ↑ "Access to sedative drug restricted". AAP General News (Australia). 13 January 2002. Archived from the original on 2008-12-28. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ↑ Wilce H (June 2004). "Temazepam capsules: What was the problem?". Australian Prescriber. 27 (3): 58–9. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2004.053.

- ↑ Australian Institute of Criminology (May 2007). "Benzodiazepine use and harms among police detainees in Australia" (PDF). Australian Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2007-11-20.

- ↑ Mouzos, J.; Smith, L.; Hind, N. (2006). "Drug Use Monitoring in Australia (DUMA): 2005 annual report on drug use among police detainees". Research and Public Policy Series. 70.

- ↑ Stafford, J.; Degenhardt, L.; Black, E.; Bruno, R.; Buckingham, K.; Fetherston, J.; Jenkinson, R.; Kinner, S.; Newman, J.; Weekley, J. (2006). Australian drug trends 2005: Findings from the Illicit Drug Reporting System (IDRS). National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Sydney.

- ↑ Ashton H (2002). "Benzodiazepine Abuse". Drugs and Dependence. London & New York: Harwood Academic Publishers.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|archive-url=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (help) - ↑ Hammersley R, Cassidy MT, Oliver J; Cassidy; Oliver (1995). "Drugs associated with drug-related deaths in Edinburgh and Glasgow, November 1990 to October 1992". Addiction. 90 (7): 959–65. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.9079598.x. PMID 7663317.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Hammersley R, Pearl S; Pearl (1997). "Temazepam Misuse, Violence and Disorder". Addict Res Theory. 5 (3): 213–22. doi:10.3109/16066359709005262.

- ↑ Kripke DF (December 15, 2007). "Who should sponsor sleep disorders pharmaceutical trials?". Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 3 (7): 671–3. doi:10.5664/jcsm.27020. PMC 2556906. PMID 18198797.

NIH or VA sponsorship of major hypnotic trials is needed to more carefully study potential adverse effects of hypnotics such as daytime impairment, infection, cancer, and death and the resultant balance of benefits and risks.

- ↑ "Temazepam information from DAN 24/7". Archived from the original on 2018-07-05. Retrieved 2018-07-04.

- ↑ "Erowid Drug Street Terms". Erowid. Archived from the original on 2008-05-02. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 74.5 74.6 "Classification of controlled drugs". EMCDDA. Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "Poisons Standard 2015" (pdf). Therapeutic Goods Administration. February 5, 2015. p. 121. Archived from the original on 2015-03-14. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- ↑ Breen CL, Degenhardt LJ, Roxburgh AD, Bruno RB, Jenkinson R; Degenhardt; Bruno; Roxburgh; Jenkinson (September 2004). "The effects of restricting publicly subsidised temazepam capsules on benzodiazepine use among injecting drug users in Australia" (PDF). Medical Journal of Australia. 181 (6): 300–304. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06293.x. PMID 15377238. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2012-09-20.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Controlled Drugs and Substance Act - Schedule IV". Government of Canada. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ↑ "Classification of controlled drugs". The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). Archived from the original on 13 August 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ↑ "Archive copy". Archived from the original on 2020-09-23. Retrieved 2020-05-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Bilingual Laws Information System" (English). The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China. Archived from the original on 2007-07-03. Retrieved 2007-11-25.

- ↑ "Misuse Of Drugs (Amendment) Regulations". Irish Statute Book. Office of the Attorney General. 1993. Archived from the original on 2015-01-30. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ↑ "Decreto-Lei n.º 15/93, de 22 de Janeiro: Regime jurídico do tráfico e consumo de estupefacientes e psicotrópicos" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Infarmed. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Narkotiska läkemedel - Läkemedelsverket / Swedish Medical Products Agency". lakemedelsverket.se. Archived from the original on 2019-01-03. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- ↑ "Verzeichnis aller zugelassenen betäubungsmittelhaltigen Präparate im Schweizer Handel Indice de tous les stupéfiants autorisés sur le marché suisse Stand/Etat 01.07.2011". Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Blackpool NHS Primary Care Trust (2007). "Medicines Management Update" (PDF). United Kingdom: National Health Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-04.

- ↑ "List of drugs currently controlled under the misuse of drugs legislation" (PDF). UK Government Home Office. 2009-01-28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2009-05-27.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "Green List—List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF) (24th ed.). International Narcotics Control Board. May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-13. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

- ↑ Bell, S. C.; Childress, S. J. (1962). "A Rearrangement of 5-Aryl-1,3-dihydro-2H-1,4-benzodiazepine-2-one 4-Oxides". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 27 (5): 1691–1695. doi:10.1021/jo01052a049.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Temazepam | Inchem Archived 2006-02-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Panorama document - 1995 - YouTube video Archived 2017-09-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from October 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with permanently dead external links

- CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2020

- CS1: long volume value

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- CS1 maint: url-status

- CS1 maint: uses authors parameter

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- CS1 errors: access-date without URL

- CS1 errors: archive-url

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Wikipedia articles needing clarification from October 2015

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from October 2016

- Articles with changed DrugBank identifier

- Webarchive template wayback links

- RTT

- Benzodiazepines

- Chloroarenes

- Lactams

- Lactims

- GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators