Pandemrix

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Pandemic H1N1/09 virus |

| Type | Inactivated |

| Clinical data | |

| Routes of use | Intramuscular injection |

| Legal | |

| Legal status |

|

Pandemrix is an influenza vaccine for influenza pandemics, such as the 2009 flu pandemic. The vaccine was developed by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK)[2] and patented in September 2006.[3]

The vaccine was one of the H1N1 vaccines approved for use by the European Commission in September 2009, upon the recommendations of the European Medicines Agency (EMEA).[4] The vaccine is only approved for use when an H1N1 influenza pandemic has been officially declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) or European Union (EU).[4] The vaccine was initially developed as a pandemic mock-up vaccine using an H5N1 strain.[5]

Pandemrix was found to be associated with an increased risk of narcolepsy[6] following investigations by Swedish and Finnish health authorities[7] and had higher rates of adverse events than other vaccines for H1N1.[8] This resulted in several legal cases.[9] Stanford University studies suggested that narcolepsy is an autoimmune disease[10] and that it appears to be triggered by upper airway respiratory infections.[11]

In 2018, a study team including Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) scientists analyzed and published vaccine safety data on adjuvanted pH1N1 vaccines (arenaprix-AS03, Focetria-MF59, and Pandemrix-AS03) from 10 global study sites. Researchers did not detect any associations between the vaccines and narcolepsy.[12]

Constituents

| Influenza (Flu) |

|---|

|

As well as the active antigen derived from A/California/7/2009 (H1N1), the vaccine contains an immunologic adjuvant AS03 which consists of DL-α-tocopherol (vitamin E), squalene and polysorbate 80.[citation needed]

Thiomersal (thimerosal) is added as a preservative. Being manufactured in chicken eggs, it contains trace amounts of egg proteins. Additional important non-medicinal ingredients are formaldehyde, sodium deoxycholate, and sucrose.[13]

Use of adjuvant

While other 2009 H1N1 vaccines have been developed, the use of a proprietary immunologic adjuvant is claimed to boost the potency of the body's immune response, meaning that only a quarter of the inactivated virus is needed.[13]

Professor David Salisbury, Head of Immunisation at the UK Department of Health said the vaccines with adjuvants offer good protection even if the virus changes over time; "One of the advantages with adjuvanted vaccines is their ability to protect against drifted (mutated) strains. It opens the door for a whole new strategy in dealing with flu."[14]

Dosage

The vaccine is supplied in separate vials, one containing the adjuvant, and the other the inactivated virus,[15] which require mixing before intramuscular injection. Originally it was thought that two doses given 21 days apart would be required for full efficacy.[16] Subsequent testing has allowed the UK programme to consist of just a single dose for most people, with a two-dose schedule for children under the age of 10 years and immunocompromised adults.[17]

Availability

Pandemrix was given to around 70 million individuals, including 31 million Europeans following the 2009 swine flu pandemic.[18][19]

The Marketing Authorisation from the European Medicines Agency expired in August 2015 when GSK Biologicals did not apply for renewal of it citing lack of demand for the vaccine.[20]

Clinical trials

The EMEA reported results from some clinical trials in the CHMP Assessment Report. These relate to vaccination against H5N1 (Bird Flu) and not H1N1 (Swine Flu).[21]

- H5N1-007 was initiated at a single site in Belgium (Ghent) in March 2006.

- H5N1-008 was initiated at 41 sites in seven countries (6 EU MS plus Russia) in May 2006.

- H5N1-002 was initiated on 24 March 2007 in four SE Asian countries.

GlaxoSmithKline reported results from the second clinical trial,[22] from the pediatric clinical trial,[23] and the response from the elderly population.[24]

Side effects

According to GlaxoSmithKline's Patient Information Leaflet,[25] the following side effects may occur (sorted by rate of occurrence):[citation needed]

- Very common (affects more than 1 in 10 people)

- Headache

- Tiredness

- Pain, redness, swelling or a hard lump at the injection site

- Fever

- Aching muscles, joint pain

- Common (affects at least 1 in 100 people)

- Warmth, itching or bruising at the injection site

- Increased sweating, shivering, flu-like symptoms

- Swollen glands in the neck, armpit or groin

- Uncommon (affects at least 1 in 1,000 people)

- Tingling or numbness of the hands or feet

- General constitutional upset of sleepiness or sleeplessness, generally feeling unwell, dizziness.

- Diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pain, feeling sick

- Skin reactions of itching, rash or urticaria (hives)

- Rare (affects at least 1 in 10,000 people)

- Serious generalised allergic reactions of anaphylaxis

- Fits

- Severe stabbing or throbbing pain along one or more nerves

- Low blood platelet count which can result in bleeding or bruising

- Very Rare (affects less than 1 in 10,000 people)

- Vasculitis

- Neurological disorders such as encephalomyelitis, neuritis or Guillain–Barré syndrome temporary paralysis

Adverse outcomes

Narcolepsy

Pandemrix was found to be associated with narcolepsy from observational studies, increasing the risk of narcolepsy by 5-14 times in children and 2-7 times in adults. The increased risk of narcolepsy due to vaccination in children and adolescents was around 1 incident per 18,400 doses.[6] In 2018, it was demonstrated that T-cells stimulated by Pandemrix were cross-reactive by molecular mimicry with part of the hypocretin peptide, the loss of which is associated with type I narcolepsy.[27]

The British Medical Journal obtained adverse event report data from GSK and conducted an analysis of that data, which showed that Pandemrix was associated with adverse events much more frequently than the two other GSK H1N1 vaccines. The risk of adverse events after Pandemrix was more than five times higher than the risk after the other two GSK H1N1 vaccines. Vaccination had continued after the figures that allowed this analysis became available. In the Irish parliament, TD Clare Daly commented that, “The Health Service Executive (HSE) decided to purchase Pandemrix and continued to distribute it even after they knew it was dangerous and untested, and before most of the public in Ireland received it.”[8]

There were multiple legal cases by individuals who attributed medical conditions to the Pandemrix vaccination.[9] One well known example was the case of Katie Clack, a nurse who committed suicide after developing narcolepsy after receiving a vaccination. Clack was required to be vaccinated against her wishes in order to continue her job as a nurse.[28]

In August 2010, The Swedish Medical Products Agency (MPA) and The Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) launched investigations regarding the development of narcolepsy as a possible side effect to Pandemrix flu vaccination in children.[7]

In summer 2010, the MPA and THL received reports from Swedish and Finnish healthcare professionals that narcolepsy was a suspected adverse drug reaction to the Pandemrix flu vaccination. The reports concern children 12 to 16 years old, whose symptoms occurred one to two months after vaccination. The symptoms were later confirmed to be compatible with narcolepsy. Consumer reports describing similar symptoms were also received. Both organizations, in consultation with external experts, have assessed the possible relationship between the vaccination and the reported reactions. MPA and THL have been in contact with other EU member states to enquire whether there have been any similar reports in other countries.[citation needed]

THL recommended that further Pandemrix vaccinations be discontinued pending further investigation into 15 cases of recently vaccinated children who developed narcolepsy in late 2009 and early 2010.[29] THL later raised this figure to 17; the expected average annual occurrence is 6 cases. In Sweden, MPA has discovered 12 confirmed cases and another 12 suspected cases. Additionally, MPA says it is aware of individual case reports from France, Norway and Germany.[30]

On 27 August 2010, the European Medicines Agency announced that the agency's Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use would be launching a review of Pandemrix in light of the "limited number of cases"[31] reported in Finland and Sweden, so as to "determine whether there is evidence for a causal association".[32]

In August 2010 the Swedish MPA issued a statement which included the following: "An investigation is ongoing, but any relationship between the vaccination and the reported symptoms can not be concluded."[33]

In February 2011, THL concluded that there is a clear connection between the Pandemrix vaccination campaign of 2009 and 2010 and the narcolepsy epidemic in Finland. The probability of developing narcolepsy was determined to be nine times higher in those who received the Pandemrix vaccination than those who didn't. A total of 152 cases of narcolepsy have been found in Finland during 2009–2010, and ninety percent of them had received the Pandemrix vaccination. Authorities believe that the number of cases may still increase.[34][35][36]

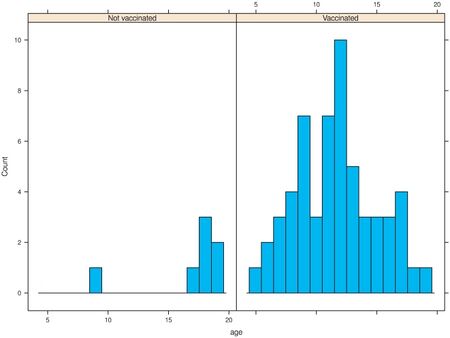

At the end of March 2011, an MPA press release stated: "Results from a Swedish registry based cohort study indicate a 4-fold increased risk of narcolepsy in children and adolescents below the age of 20 vaccinated with Pandemrix, compared to children of the same age that were not vaccinated."[37] The same study found no increased risk in adults who were vaccinated with Pandemrix. While cautioning that the increase in risk for children is still uncertain in magnitude, it recommends they not be vaccinated.[citation needed]

A study by the Stanford University School of Medicine examined the incidence of narcolepsy in relation to upper airway infection and a H1N1 vaccine (not Pandemrix) in Chinese patients. Their principal conclusion was that an increased incidence of narcolepsy was seen following a wave of upper airway infections (such as H1N1 influenza). They found no correlation between vaccination and narcolepsy. According to the authors, "the new finding of an association with infection, and not vaccination, is important as it suggests that limiting vaccination because of a fear of narcolepsy could actually increase overall risk."[11] Since narcolepsy is now believed to be an autoimmune disease,[10] the authors suspect that these upper airway infections trigger an immune response which leads ultimately to narcolepsy in susceptible individuals. Pandemrix contains two adjuvants designed to provoke a stronger immune response; they were not in the vaccine used in China, however.[citation needed]

In 2013, the New Scientist reported that "part of a surface protein on the pandemic virus looks very similar to part of a brain protein that helps keep people awake".[38] However, the original scientific article claiming that HA protein in both the virus and the vaccine could, in some people, trigger an immune reaction against hypocretin, was retracted in 2014 because the data could not be reproduced.[39] However, further investigations indicated that "antibodies to influenza nucleoprotein cross-react with human hypocretin receptor 2".[40][41]

In 2014, a Finnish group published results that showed Pandemrix contained a higher amounts of structurally altered viral nucleoproteins than Arepanrix, a similar vaccine not associated with narcolepsy.[42]

In 2015, it was reported that the British Department of Health was paying for sodium oxybate medication for 80 patients who are taking legal action over problems linked to the use of the swine flu vaccine, at a cost to the government of £12,000 per patient per year. Sodium oxybate is not available to patients with narcolepsy through the National Health Service.[43]

In 2018, a multinational study including Centers for Disease Control and Prevention scientists published safety data on adjuvanted pH1N1 vaccines. Sweden was the only country where increased narcolepsy IRs were found in the period after vaccination campaigns. The ability of the researchers to evaluate the Pandemrix brand vaccine was limited.[44]

In December 2018, T-cells were demonstrated to be cross-reactive to both a particular piece of the pandemic 2009 H1N1 virus and the amidated terminal ends of hypocretin peptides, the loss of which is associated with type I narcolepsy. Genes associated with narcolepsy modulate the expression of the specific T cell receptor recognition involved in reaction to these antigens, suggesting H1N1 infection is a cause of narcolepsy in genetically susceptible individuals. T-cells stimulated by Pandemrix were cross-reactive by molecular mimicry with the same part of the hypocretin peptide.[27]

See also

- Oseltamivir and Zanamivir – antiviral drugs used in the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza

- Influenza vaccine

- 2009 flu pandemic vaccine

References

- ↑ "Pandemrix EPAR". European Medicines Agency. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ↑ "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza Update: GSK's H1N1 'Pandemrix' vaccine receives positive opinion from European Regulators" (Press release). GlaxoSmithKline. 25 September 2009. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ WO 2006100109, Hanon, Emmanuel Jules & Jean Stephenne, "Use of an influenza virus an oil-in-water emulsion adjuvant to induce CD4 T-cell and/or improved B-memory cell response", published 2006-09-28, assigned to Glaxosmithkline Biolog SA

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "EMEA Pandemrix page". Emea.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 8 October 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "Assessment report for the mock-up H5N1 vaccine" (PDF). EMEA. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 2, 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Sarkanen TO, Alakuijala AP, Dauvilliers YA, Partinen MM (April 2018). "Incidence of narcolepsy after H1N1 influenza and vaccinations: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 38: 177–186. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2017.06.006. hdl:10138/300884. PMID 28847694.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The MPA investigates reports of narcolepsy in patients vaccinated with Pandemrix". The Swedish Medical Products Agency. 2010-08-18. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 2010-08-19.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Doshi, Peter (2018-09-20). "Pandemrix vaccine: why was the public not told of early warning signs?". BMJ. 362: k3948. doi:10.1136/bmj.k3948. PMID 30237282. S2CID 52308748.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Devlin, Hannah (2015-06-10). "Boy wins £120,000 damages for narcolepsy triggered by swine flu vaccine". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2020-11-19. Retrieved 2020-11-20.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Narcolepsy is an autoimmune disorder, Stanford researcher says". 3 May 2009. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Study draws connection between narcolepsy and influenza". Archived from the original on 2012-10-01. Retrieved 2012-10-01.

- ↑ "Narcolepsy Following 2009 Pandemrix Influenza Vaccination in Europe | Vaccine Safety | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2020-08-20. Archived from the original on 2016-06-27. Retrieved 2023-01-16.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Leroux-Roels I, Bernhard R, Gérard P, Dramé M, Hanon E, Leroux-Roels G (February 2008). "Broad Clade 2 cross-reactive immunity induced by an adjuvanted clade 1 rH5N1 pandemic influenza vaccine". PLOS ONE. 3 (2): e1665. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.1665L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001665. PMC 2253495. PMID 18301743.

- ↑ Smith, Rebecca (2009-12-03). "Change in swine flu virus is my biggest fear: Liam Donaldson". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2009-12-06. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ↑ "Pandemrix packaging information" (PDF). EMEA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-10-15. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ "Pandemrix, INN-Influenza vaccine (H1N1)v (split virion, inactivated, adjuvanted)" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ↑ Department of Health (UK) (19 October 2009). "Information sheet on the swine flu vaccination" (PDF). p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 2009-11-10.

- ↑ "Swine flu vaccine can trigger narcolepsy, UK government concedes". the Guardian. 2013-09-19. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-11-20.

- ↑ Doshi, Peter (2018-09-20). "Pandemrix vaccine: why was the public not told of early warning signs?". BMJ. 362. Article Infographic at https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/suppl/2018/09/20/bmj.k3948.DC1/pandremix1809.ww2.pdf. doi:10.1136/bmj.k3948. ISSN 0959-8138. PMID 30237282. S2CID 52308748. Archived from the original on 2023-07-01. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

the doses of Pandemrix administered went ... to 70 million

- ↑ European Medicines Agency, Public Statement, EMA/656472/2015 "Pandemrix Expiry of the marketing authorisation in the European Union" Archived 2021-03-20 at the Wayback Machine 19 October 2015

- ↑ "CHMP Assessment Report for Pandemrix" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 24 September 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-10-25. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza Update: Results from second clinical trial of GSK's H1N1 adjuvanted vaccine confirm immune response and tolerability" (Press release). GlaxoSmithKline. 16 October 2009. Archived from the original on October 31, 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Influenza Update: Experience of GSK's H1N1 adjuvanted vaccine, Pandemrix, and preliminary paediatric results" (Press release). GlaxoSmithKline. 23 October 2009. Archived from the original on October 29, 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ "Pandemic 2009 Influenza Update: Pandemrix data in an elderly population" (Press release). 27 October 2009. Archived from the original on October 29, 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ "Pandemrix Package Leaflet" (PDF). Who.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-26. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ Nohynek, Hanna; Jokinen, Jukka; Partinen, Markku; Vaarala, Outi; Kirjavainen, Turkka; Sundman, Jonas; Himanen, Sari-Leena; Hublin, Christer; Julkunen, Ilkka; Olsén, Päivi; Saarenpää-Heikkilä, Outi; Kilpi, Terhi (28 March 2012). "AS03 Adjuvanted AH1N1 Vaccine Associated with an Abrupt Increase in the Incidence of Childhood Narcolepsy in Finland". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e33536. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033536. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Luo G, Ambati A, Lin L, Bonvalet M, Partinen M, Ji X, et al. (December 2018). "Autoimmunity to hypocretin and molecular mimicry to flu in type 1 narcolepsy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (52): E12323–E12332. Bibcode:2018PNAS..11512323L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1818150116. PMC 6310865. PMID 30541895.

- ↑ "Swine flu jab 'most likely' led to narcolepsy in nurse who killed herself – coroner". The Guardian. Press Association. 2016-08-11. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 2020-11-12. Retrieved 2020-11-20.

- ↑ "National Institute for Health and Welfare recommends discontinuation of Pandemrix vaccinations". National Institute of Health and Welfare. 2010-08-25. Archived from the original on 2010-08-27. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "Aktuell information om utredningen av fall av narkolepsi efter vaccination med Pandemrix". Medical Products Agency (in svenska). 2010-08-26. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "EU regulator probes swine flu vaccine over narcolepsy fears". medicalxpress.com. 2010-08-27. Archived from the original on 2020-06-02. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ↑ Kirby, Jane (2010-08-27). "Swine flu vaccine link to narcolepsy probed". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 2022-05-24. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ↑ "Current information on the investigation of cases of narcolepsy after vaccination with Pandemrix - Swedish Medical Products Agency". Lakemedelsverket.se. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "THL: Pandemrixilla ja narkolepsialla on selvä yhteys". Mtv3.fi (in suomi). 1 February 2011. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos - THL". Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "Narkolepsia ja sikainfluenssarokote - THL". Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "A Swedish registry based cohort study provides strengthened evidence of an association between vaccination with Pandemrix and narcolepsy in children and adolescents - Swedish Medical Products Agency". Lakemedelsverket.se. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ "Flu vaccine helps unravel complex causes of narcolepsy". New Scientist. 2013-12-19. Archived from the original on 2015-04-25. Retrieved 2014-01-03.

- ↑ "Journal retracts paper linking vaccine and narcolepsy". Nature News Blog. 2014-07-31. Archived from the original on 2014-10-11. Retrieved 2014-10-07.

- ↑ Ahmed SS, Volkmuth W, Duca J, Corti L, Pallaoro M, Pezzicoli A, et al. (July 2015). "Antibodies to influenza nucleoprotein cross-react with human hypocretin receptor 2". Science Translational Medicine. 7 (294): 294ra105. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aab2354. PMID 26136476.

- ↑ "Why a pandemic flu shot caused narcolepsy". Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- ↑ Vaarala O, Vuorela A, Partinen M, Baumann M, Freitag TL, Meri S, et al. (2014). "Antigenic differences between AS03 adjuvanted influenza A (H1N1) pandemic vaccines: implications for pandemrix-associated narcolepsy risk". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e114361. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k4361V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0114361. PMC 4266499. PMID 25501681.

- ↑ "DH funds private prescriptions for drug denied to NHS patients". Health Service Journal. 20 July 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ↑ Weibel D, Sturkenboom M, Black S, de Ridder M, Dodd C, Bonhoeffer J, et al. (October 2018). "Narcolepsy and adjuvanted pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 vaccines - Multi-country assessment". Vaccine. CDC. 36 (41): 6202–6211. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.08.008. PMC 6404226. PMID 30122647.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- CDC: Narcolepsy Following Pandemrix Influenza Vaccination in Europe Archived 2016-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Pandemrix: further information on product characteristics and studies

- A study of side-effects of Pandemrix influenza (H1N1) vaccine on board a Norwegian naval vessel Archived 2021-07-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 svenska-language sources (sv)

- CS1 suomi-language sources (fi)

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without InChI source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugs that are a vaccine

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2022

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2020

- Chemicals that do not have a ChemSpider ID assigned

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Prevention

- Influenza vaccines

- Inactivated vaccines

- 2009 swine flu pandemic

- Influenza A virus subtype H1N1

- Influenza

- GSK plc brands