Stiff-person syndrome

| Stiff-person disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Stiff-man syndrome (SMS), Moersch-Woltman syndrome[1] | |

| |

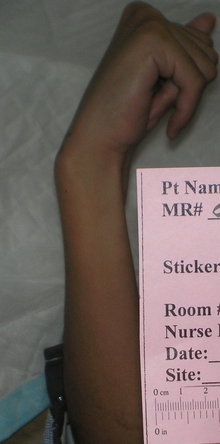

| Wrist in fist-like position | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Stiff muscles, spasms, pain[2][3] |

| Complications | Poor posture, bone fractures, frequent falls, lumbar hyperlordosis[2][1] |

| Usual onset | 20 to 60[3] |

| Duration | Progressive worsening[3] |

| Types | Classic, partial, progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus (PERM)[3] |

| Causes | Unclear, autoimmune mechanism[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and supported by blood tests and electromyography[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Parkinsons, multiple sclerosis, fibromyalgia, psychosomatic illness, anxiety[2] |

| Treatment | Diazepam, baclofen, gabapentin, intravenous immunoglobulin[2][4] |

| Prognosis | Often poor[4][5] |

| Frequency | Rare[1] |

Stiff-person syndrome (SPS) is a neurologic disorder characterized by stiff muscles and spasms which worsen over time.[1][2] It primarily affects the torso, arms, and legs.[2] Spasms can be triggered by sound, touch, or emotions.[1] Complications may include poor posture, bone fractures, chronic pain, and frequent falls.[1][2][4]

In most cases the cause is unclear, though an autoimmune mechanism is believed to be involved.[2] Many cases are associated with other autoimmune conditions, such as type 1 diabetes.[5] Uncommonly it occurs as a paraneoplastic syndrome.[4][5] Diagnosis is often by finding very high levels of antibodies to glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) in the blood or cerebral spinal fluid.[2][4] Electromyography may also be useful.[1]

Symptoms may be treated with medications such as diazepam, baclofen, or gabapentin.[2] Intravenous immunoglobulin or plasmapheresis may also help.[2][4] It generally results in a poor quality of life, with depression or anxiety often occurring as a result.[4][5] Life expectancy is reduced.[5]

Stiff-person syndrome is rare, occurring in about one in a million people.[4] Onset is most often between the ages of 20 and 60, though may uncommonly occur in children.[3] Women are affected twice as often as men.[2] The condition was first described in 1956 by Frederick Moersch and Henry Woltman.[3]

Signs and symptoms

People experience progressive stiffness in their truncal muscles (torso muscles),[6] which become rigid and stiff because the lumbar and abdominal muscles engage in constant contractions.[5] Initially, stiffness occurs in the thoracolumbar paraspinal and abdominal muscles.[7] It later affects the proximal leg and abdominal wall muscles.[6] The stiffness leads to a change in posture,[8] and development of a rigid gait.[6] Persistent lumbar hyperlordosis often occurs as it progresses.[5] The muscle stiffness initially fluctuates, sometimes for days or weeks, but eventually begins to consistently impair mobility.[6] As the disease progresses, people sometimes become unable to walk or bend.[7] Chronic pain is common and worsens over time but sometimes acute pain occurs as well.[5] Stress, cold weather, and infections lead to an increase in symptoms, and sleep decreases them.[6]

People experience superimposed spasms and extreme sensitivity to touch and sound.[6] These spasms primarily occur in the proximal limb and axial muscles.[9] There are co-contractions of agonist and antagonist muscles. Spasms usually last for minutes and can recur over hours. Attacks of spasms are unpredictable and are often caused by fast movements, emotional distress, or sudden sounds or touches.[7] In rare cases, facial muscles, hands, feet, and the chest can be affected and unusual eye movements and vertigo occur.[10][5] There are brisk stretch reflexes and clonus occurs.[6] Late in the disease's progression, hypnagogic myoclonus can occur.[11] Tachycardia and hypertension are sometimes also present.[12]

Because of the spasms, people may become increasingly fearful, require assistance, and lose the ability to work, leading to depression, anxiety, and phobias,[6] including agoraphobia[13] and dromophobia.[14] Most people are psychologically normal and respond reasonably to their situations.[15]

Paraneoplastic SPS tends to affect the neck and arms more than other variations.[5] It progresses very quickly, is more painful, and is more likely to include distal pain than classic SPS.[16] People with paraneoplastic SPS generally lack other autoimmune issues[17] but may have other paraneoplastic conditions.[16]

Stiff-limb syndrome is a variant of SPS.[5] This syndrome develops into full SPS about 25% of the time. Stiffness and spasms are usually limited to the legs and hyperlordoisis generally does not occur.[18] The stiffness begins in one limb and remains most prominent there. Sphincter and brainstem issues often occur with stiff-limb syndrome.[5] Progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity, another variant of the condition,[5] includes symptoms of SPS with brainstem issues and autonomic disturbances.[5] It involves polio-encephalomyelitis in the spine and brainstem. There is cerebellar and brainstem involvement. In some cases, the limbic system is affected, as well. Most have upper motor neuron issues and autonomic disturbances.[19] Jerking SPS is another subtype of the condition.[13][18] It begins like classical SPS[18] and progresses for several years; up to 14 in some cases. It is then distinguished by the development of myoclonus as well as seizures and ataxia in some cases.[19]

Cause

People generally have high glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody levels in their blood.[20] About 80 percent of SPS have GAD antibodies, compared with about one percent of the general population.[21] The overwhelming majority of people who have GAD antibodies do not develop SPS, indicating that systemic synthesis of the antibody is not the sole cause of SPS.[22] GAD, a presynaptic autoantigen, is generally thought to play a key role in the condition, but exact details of the way that autoantibodies affect SPS are not known.[5] Most SPS with high-titer GAD antibodies also have antibodies that inhibit GABA-receptor-associated protein (GABARAP).[6] Autoantibodies against amphiphysin and gephyrin are also sometimes found in SPS.[5] The antibodies appear to interact with antigens in the brain neurons and the spinal cord synapses, causing a functional blockade of the inhibitory neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[6] This leads to GABA impairment, which probably causes the stiffness and spasms that characterize SPS.[20] There are low GABA levels in the motor cortexes of SPS.[6]

It is not known why GAD autoimmunity occurs,[23] and whether SPS qualifies as a neuro-autoimmune disorder has been questioned.[24] It is also unknown whether these antibodies are pathogenic.[23] The level of GAD antibody titers found in SPS does not correlate with disease severity,[20] indicating that these titer levels do not need to be monitored.[5] It has not been proven that GAD antibodies are the sole cause of SPS, and the possibility exists that they are a marker or an epiphenomenon of the condition's cause.[25]

In SPS, motor unit neurons fire involuntarily in a way that resembles a normal contraction. Motor unit potentials fire while the person is at rest, particularly in the muscles which are stiff.[6] The excessive firing of motor neurons may be caused by malfunctions in spinal and supra-segmental inhibitory networks that utilize GABA.[6] Involuntary actions show up as voluntary on EMG scans:[11] even when the person tries to relax, there are agonist and antagonist contractions.[21]

In a minority of SPS, breast, ovarian, or lung cancer is manifesting paraneoplasticly as proximal muscle stiffness. These cancers are associated with the synaptic proteins amphiphysin and gephyrin. Paraneoplastic SPS with amphiphysin antibodies and breast adenocarcinoma tend to occur together. These people tend not to have GAD antibodies.[6] Passive transfer of SPS by plasma injection has been demonstrated in paraneoplastic SPS but not in classical SPS.[25]

There is evidence of genetic influence on SPS risk. The HLA class II locus makes people susceptible to the condition. Most SPS have the DQB1* 0201 allele.[6] This allele is also associated with type 1 diabetes.[26]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is by evaluating symptoms and excluding other conditions.[6] There is no specific laboratory test that confirms the condition.[5] Underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis are common.[20]

The presence of antibodies against GAD is the best indication of the condition that can be detected by blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing. Anti-GAD65 is found in about 80 percent of SPS. Anti-thyroid, anti-intrinsic factor, anti-nuclear, anti-RNP, and anti-gliadin are also often found in blood tests. Electromyography (EMG) demonstrates involuntary motor unit firing in SPS.[6] EMG can confirm the SPS diagnosis by noting spasms in distant muscles as a result of subnoxious stimulation of cutaneous or mixed nerves.[11] Responsiveness to diazepam helps confirm SPS, as this drug will decrease stiffness and motor unit firing.[6]

The same general criteria are used to diagnose paraneoplastic SPS as for the normal form of the condition.[15] Once SPS is diagnosed, poor response to conventional therapies and the presence of cancer indicate that it may be paraneoplastic.[6] CT scans are indicated for cases which respond poorly to therapy to determine if cancer is the cause.[27]

A variety of conditions have similar symptoms to SPS, including myelopathies, dystonias, spinocerebellar degenerations, primary lateral sclerosis, neuromyotonia, and some psychogenic disorders.[6] Tetanus, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, malignant hyperpyrexia, chronic spinal interneuronitis, serotonin syndrome,[28] multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease,[21] and Isaacs syndrome should also be excluded.[28]

Peoples fears and phobias often incorrectly lead doctors to think their symptoms are psychogenic,[8] and they are sometimes suspected of malingering.[5] It takes an average of six years after the onset of symptoms before the disease is diagnosed.[8]

Treatment

There is no evidence-based specific treatment. The rarity of the disease complicates efforts to establish guidelines.[28]

A small trial found immunoglobulin therapy to be a "well-tolerated and effective".[29]

GABAA agonists,[6] usually diazepam but sometimes other benzodiazepines,[5] are the primary treatment for SPS. Drugs that increase GABA activity alleviate muscle stiffness caused by a lack of GABAergic tone.[6] They increase pathways that are dependent upon GABA and have muscle relaxant and anticonvulsant effects, often providing symptom relief.[5] Because the condition worsens over time, people generally require increased dosages, leading to more side effects.[6] For this reason, gradual increase in dosage of benzodiazepines is indicated.[5] Baclofen, a GABAB agonist, is generally used when individuals taking high doses of benzodiazepines have high side effects. In some cases it has shown improvements in electrophysiological and muscle stiffness when administered intravenously.[5] Intrathecal baclofen administration may not have long-term benefits though, and there are potential serious side effects.[6]

Therapies that target the autoimmune response are also used.[27] Intravenous immunoglobin is the best second-line treatment for SPS. It often decreases stiffness and improves quality of life and startle reflex. It is generally safe, but there are possible serious side effects and it is expensive.[30] The European Federation of Neurological Societies suggests it be used when disabled people do not respond well to diazepam and baclofen.[5] Steroids and plasma exchange have been used to suppress the immune system. Plasma exchange, or plasmapheresis, may benefit people who do not respond to first-line therapy, specifically beneficial for anti-GAD65 positive cases.[28] Botulinum toxin has been used, but it does not appear to have long-term benefits and has potential serious side effects.[6] In paraneoplastic cases, tumors must be managed for the condition to be contained.[6] Opiates are sometimes used to treat severe pain, but they may exacerbate symptoms.[5][31]

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) with high intensity conditioning protocol has been performed in a few cases with severe anti-GAD positive SPS, resulting in clinical remission.[32] In carefully selected cases of severe, treatment refractory SPS, HSCT may be an effective therapeutic option.[33]

Non effective

Rituximab has not been found to be useful.[2]

Prognosis

The progression of SPS depends on whether it is a typical or abnormal form of the condition and the presence of comorbidities. Early recognition and neurological treatment can limit its progression. SPS is generally responsive to treatment,[5] but the condition usually progresses and stabilizes periodically.[34] Even with treatment, quality of life generally declines as stiffness precludes many activities.[5] Some require mobility aids due to the risk of falls.[5] About 65 percent are unable to function independently.[5] About ten percent require intensive care at some point;[34] sudden death occurs in about the same number.[5] These deaths are usually caused by metabolic acidosis or an autonomic crisis.[34]

Epidemiology

SPS is estimated to have a prevalence of about one per million. Underdiagnosis and misdiagnosis hinder epidemiological information about the condition[20] and may have led to its prevalence being underestimated.[13] In the United Kingdom, 119 cases were identified between 2000 and 2005.[5] It does not predominantly occur in any racial or ethnic group.[20] The age of onset varies from about 30 to 60,[5] and it most frequently occurs in people in their 40s.[20] Five to ten percent of SPS have the paraneoplastic variant of the condition.[16] In one group of 127, only 11 of them had paraneoplastic symptoms.[35] About 35 percent of SPS have type I diabetes.[6]

History

SPS was first described by Moersch and Woltman in 1956. Their description of the disease was based on 14 cases that they had observed over 32 years. Using electromyography, they noted that motor-unit firing suggested that voluntary muscle contractions were occurring.[5] Previously, cases of SPS had been dismissed as psychogenic problems.[12] Moersch and Woltman initially called the condition "stiff-man syndrome", but the first female cases was confirmed in 1958[9] and a young boy was confirmed to have it in 1960.[36] Clinical diagnostic criteria were developed by Gordon et al. in 1967. They observed "persistent tonic contraction reflected in constant firing, even at rest" after providing people with muscle relaxants and examining them with electromyography.[5] In 1989, criteria for an SPS diagnosis were adopted that included episodic axial stiffness, progression of stiffness, lordosis, and triggered spasms.[36] The name of the disease was shifted from "stiff-man syndrome" to the gender-neutral "stiff-person syndrome" in 1991.[36]

In 1963, it was determined that diazepam helped alleviate symptoms of SPS.[6] Corticosteroids were first used to treat the condition in 1988, and plasma exchange was first applied the following year.[5] The first use of intravenous immunoglobulin to treat the condition came in 1994.[5]

In 1988, Solimena discovered that autoantibodies against GAD played a key role in SPS.[5] Two years later, Solimena found the antibodies in 20 out of 33 people examined.[13] In the late 1980s, it was also demonstrated that the serum of SPS would bind to GABAergic neurons.[23] In 2006, the role of GABARAP in SPS was discovered.[5] The first case of paraneoplastic SPS was found in 1975.[35] In 1993, antiamphiphysin was shown to play a role in paraneoplastic SPS,[5] and seven years later antigephyrin was also found to be involved in the condition.[5]

In December 2022, singer Céline Dion announced that she had this syndrome, resulting in cancelled performances.[37]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Stiff person syndrome - About the Disease - Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 "Stiff-Person Syndrome | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Muranova, A; Shanina, E (January 2022). "Stiff Person Syndrome". PMID 34424651.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Ortiz, JF; Ghani, MR; Morillo Cox, Á; Tambo, W; Bashir, F; Wirth, M; Moya, G (9 December 2020). "Stiff-Person Syndrome: A Treatment Update and New Directions". Cureus. 12 (12): e11995. doi:10.7759/cureus.11995. PMID 33437550.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 5.25 5.26 5.27 5.28 5.29 5.30 5.31 5.32 5.33 5.34 5.35 5.36 5.37 5.38 5.39 Hadavi, S; Noyce, AJ; Leslie, RD; Giovannoni, G (October 2011). "Stiff person syndrome". Practical neurology. 11 (5): 272–82. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2011-000071. PMID 21921002.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 Rakocevic & Floeter 2012.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Ciccotto, Blaya & Kelley 2013, p. 321.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Alexopoulos & Dalakas 2010, p. 1018.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ciccotto, Blaya & Kelley 2013, p. 319.

- ↑ Darnell & Posner 2011, p. 168.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Ciccotto, Blaya & Kelley 2013, p. 322.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Duddy & Baker 2009, p. 148.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Holmøy & Geis 2011, p. 55.

- ↑ Ana Claudia Rodrigues de Cerqueira; José Marcelo Ferreira Bezerra; Márcia Rozentha; Antônio Egídio Nardi, "Stiff-Person syndrome and generalized anxiety disorder", Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, vol.68 no.4, August 2010, doi:10.1590/S0004-282X2010000400036

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Darnell & Posner 2011, p. 166.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Darnell & Posner 2011, p. 167.

- ↑ Darnell & Posner 2011, p. 169.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Duddy & Baker 2009, p. 158.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Duddy & Baker 2009, p. 159.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 Ciccotto, Blaya & Kelley 2013, p. 320.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Alexopoulos & Dalakas 2010, p. 1019.

- ↑ Holmøy & Geis 2011, p. 56.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Alexopoulos & Dalakas 2010, p. 1020.

- ↑ Alexopoulos & Dalakas 2010, p. 1023.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Duddy & Baker 2009, p. 153.

- ↑ Ali et al. 2011, p. 79.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Duddy & Baker 2009, p. 154.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Ciccotto, Blaya & Kelley 2013, p. 323.

- ↑ Dalakas, Marinos C. (Dec 27, 2001). "High-Dose Intravenous Immune Globulin for Stiff-Person Syndrome". New England Journal of Medicine. 345 (26): 1870–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa01167. PMID 11756577. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ↑ Lünemann, Jan D. (Jan 6, 2015). "Intravenous immunoglobulin in neurology—mode of action and clinical efficacy". Nature Reviews Neurology. 11: 80–89. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2014.253. PMID 25561275. Archived from the original on 9 July 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

IVIg is also an effective rescue therapy in some patients with worsening myasthenia gravis, and is beneficial as a second-line therapy for dermatomyositis and stiff-person syndrome.

- ↑ Duddy & Baker 2009, p. 155.

- ↑ Sanders, Sheilagh; Bredeson, Christopher; Pringle, C. Elizabeth; Martin, Lisa; Allan, David; Bence-Bruckler, Isabelle; Hamelin, Linda; Hopkins, Harry S.; Sabloff, Mitchell (2014-10-01). "Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Stiff Person Syndrome". JAMA Neurology. 71 (10): 1296–9. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1297. ISSN 2168-6149. PMID 25155372.

- ↑ Burman, Joachim; Tolf, Andreas; Hägglund, Hans; Askmark, Håkan (2018-02-01). "Autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for neurological diseases". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 89 (2): 147–155. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2017-316271. ISSN 0022-3050. PMC 5800332. PMID 28866625.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Duddy & Baker 2009, p. 157.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Darnell & Posner 2011, p. 165.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Ali et al. 2011, p. 80.

- ↑ Dion, Céline. "Celine Dion reschedules Spring 2023 shows to 2024, and cancels eight of her summer 2023 shows". Instagram. Archived from the original on 2022-12-08. Retrieved 2022-12-08.

Bibliography

- Alexopoulos, Harry; Dalakas, Marinos (2010). "A Critical Update on the Immunopathogenesis of Stiff Person Syndrome". European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 40 (11): 1018–25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02340.x. PMID 20636380. S2CID 30688501.

- Ali, Fatima; Rowley, Merrill; Jayakrishnan, Bindu; Teuber, Suzanne; Gershwin, Eric; Mackay, Ian (2011). "Stiff-Person Syndrome (SPS) and Anti-GAD-Related CNS Degenerations: Protean Additions to the Autoimmune Central Neuropathies". Journal of Autoimmunity. 37 (2): 79–87. doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2011.05.005. PMID 21680149.

- Ciccotto, Giuseppe; Blaya, Maike; Kelley, Roger (2013). "Stiff Person Syndrome". Neurologic Clinics. 31 (1): 319–28. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2012.09.005. PMID 23186907.

- Darnell, Robert; Posner, Jerome (2011). Paraneoplastic Syndromes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977273-5.

- Duddy, Martin; Baker, Mark (2009). The Immunological Basis for Treatment of Stiff Person Syndrome. Stiff Person Syndrome. Frontiers of Neurology and Neuroscience. Vol. 26. pp. 147–66. doi:10.1159/000212375. ISBN 978-3-8055-9141-6. PMID 19349711.

- Holmøy, Trygve; Geis, Christian (2011). "The Immunological Basis for Treatment of Stiff Person Syndrome". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 231 (1–2): 55–60. doi:10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.09.014. PMID 20943276. S2CID 206274675.

- Rakocevic, Goran; Floeter, Mary Kay (2012). "Autoimmune Stiff Person Syndrome and Related Myelopathies: Understanding of Electrophysiological and Immunological Processes". Muscle Nerve. 45 (5): 623–34. doi:10.1002/mus.23234. PMC 3335758. PMID 22499087.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Stiff-Person Syndrome Information Page at NINDS Archived 2022-01-09 at the Wayback Machine