Oxybutynin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Ditropan, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Antimuscarinic[1] |

| Main uses | Overactive bladder[1] |

| Side effects | Dry mouth, dizziness, constipation, trouble sleeping, urinary tract infections[1] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth, transdermal gel, transdermal patch |

| Defined daily dose | 15 mg (by mouth)[2] 3.9 mg (skin patch)[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682141 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Protein binding | 91–93% |

| Elimination half-life | 12.4–13.2 hours |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H31NO3 |

| Molar mass | 357.494 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Oxybutynin, sold as under the brand names Ditropan among others, is a medication used to treat overactive bladder.[1] It works similar to tolterodine.[1] While used for bed wetting in children, evidence to support this use is poor.[1] It is taken by mouth or applied to the skin.[1]

Common side effects include dry mouth, dizziness, constipation, trouble sleeping, and urinary tract infections.[1] Serious side effects may include urinary retention and an increased risk of heat stroke.[1] Use in pregnancy appears safe but has not been well studied while use in breastfeeding is of unclear safety.[3] It is an antimuscarinic and works by blocking the effects of acetylcholine on smooth muscle.[1]

Oxybutynin was approved for medical use in the United States in 1975.[1] It is available as a generic medication which is inexpensive.[4] A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS less than GB£3 per month as of 2019.[5] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$14.[6] In 2017, it was the 100th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than seven million prescriptions.[7][8]

Medical use

The immediate and slow release versions work equally.[1]

In peoples with overactive bladder, transdermal oxybutynin decreased the number of incontinence episodes and increased average voided volume. There was no difference between transdermal oxybutynin and extended-release oral tolterodine.[9]

Tentative evidence supports the use of oxybutynin in excessive sweating.[10]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is 15 mg by mouth and 3.9 mg as a skin patch.[2]

Side effects

Common side effects with oxybutynin and other anticholinergics include: dry mouth, difficulty in urination, constipation, blurred vision, drowsiness, and dizziness.[11] Anticholinergics have also been known to induce delirium.[12]

Oxybutynin's tendency to reduce sweating can be dangerous. Reduced sweating increases the risk of heat exhaustion and heat stroke in apparently safe situations where normal sweating keeps others safe and comfortable.[13] Adverse effects of elevated body temperature are more likely for the elderly and for those with health issues, especially multiple sclerosis.[14]

N-Desethyloxybutynin is an active metabolite of oxybutynin that is thought responsible for much of the adverse effects associated with the use of oxybutynin.[15] N-Desethyloxybutynin plasma levels may reach as much as six times that of the parent drug after administration of the immediate-release oral formulation.[16] Alternative dosage forms have been developed in an effort to reduce blood levels of N-desethyloxybutynin and achieve a steadier concentration of oxybutynin than is possible with the immediate release form. The long-acting formulations also allow once-daily administration instead of the twice-daily dosage required with the immediate-release form. The transdermal patch, in addition to the benefits of the extended-release oral formulations, bypasses the first-pass hepatic effect that the oral formulations are subject to.[17] In those with overflow incontinence because of diabetes or neurological diseases like multiple sclerosis or spinal cord trauma, oxybutynin can worsen overflow incontinence since the fundamental problem is that the bladder is not contracting.

A large study linked the development of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia in those over 65 to the use of oxybutynin, due to its anticholinergic properties.[18]

Contraindications

Oxybutynin chloride is contraindicated in patients with untreated narrow angle glaucoma, and in patients with untreated narrow anterior chamber angles—since anticholinergic drugs may aggravate these conditions. It is also contraindicated in partial or complete obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract, hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, paralytic ileus, intestinal atony of the elderly or debilitated patient, megacolon, toxic megacolon complicating ulcerative colitis, severe colitis, and myasthenia gravis. It is contraindicated in patients with obstructive uropathy and in patients with unstable cardiovascular status in acute hemorrhage. Oxybutynin chloride is contraindicated in patients who have demonstrated hypersensitivity to the product.

Pharmacology

Oxybutynin chloride exerts direct antispasmodic effect on smooth muscle and inhibits the muscarinic action of acetylcholine on smooth muscle. It exhibits one-fifth of the anticholinergic activity of atropine on the rabbit detrusor muscle, but four to ten times the antispasmodic activity. No blocking effects occur at skeletal neuromuscular junctions or autonomic ganglia (antinicotinic effects).

Sources say the drug is absorbed within one hour and has an elimination half-life of 2 to 5 hours.[19][20][21] There is a wide variation among individuals in the drug's concentration in blood. This, and its low concentration in urine, suggest that it is eliminated through the liver.[20]

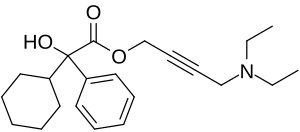

Chemistry

Oxybutynin contains one stereocenter. Commercial formulations are sold as the racemate. The (R)-enantiomer is a more potent anticholinergic than either the racemate or the (S)-enantiomer, which is essentially without anticholinergic activity at doses used in clinical practice.[22][23] However, (R)-oxybutynin administered alone offers little or no clinical benefit above and beyond the racemic mixture. The other actions (calcium antagonism, local anesthesia) of oxybutynin are not stereospecific. (S)-Oxybutynin has not been clinically tested for its spasmolytic effects, but may be clinically useful for the same indications as the racemate, without the unpleasant anticholinergic side effects.

| Enantiomers of oxybutynin | |

|---|---|

CAS-Number: 119618-21-2 |

CAS-Number: 119618-22-3 |

Society and culture

Cost

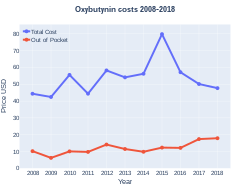

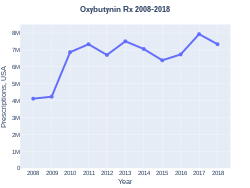

A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS less than GB£3 per month as of 2019.[5] The branded form is significantly more expensive.[4] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$14.[6] In 2017, it was the 100th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than seven million prescriptions.[7][8]

-

Oxybutynin costs (US)

-

Oxybutynin prescriptions (US)

Brandnames

Oxybutynin is available by mouth in generic formulation or as the brand-names Ditropan,[24] Lyrinel XL, or Ditrospam, as a transdermal patch under the brand name Oxytrol, and as a topical gel under the brand name Gelnique.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 "Oxybutynin Chloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ↑ "Oxybutynin Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hitchings, Andrew; Lonsdale, Dagan; Burrage, Daniel; Baker, Emma (2019). The Top 100 Drugs: Clinical Pharmacology and Practical Prescribing (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-0-7020-7442-4. Archived from the original on 2021-05-22. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 British National Formulary: BNF 76 (76th ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 2019-03-06. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 12 February 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Oxybutynin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ Baldwin C, Keating GM (2009). "Transdermal Oxybutynin". Drugs. 69 (3): 327–337. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969030-00008. PMID 19275276.

- ↑ Cruddas, L; Baker, DM (June 2017). "Treatment of primary hyperhidrosis with oral anticholinergic medications: a systematic review". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 31 (6): 952–963. doi:10.1111/jdv.14081. PMID 27976476.

- ↑ Mehta D (Ed.) 2006. British National Formulary 51. Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 0-85369-668-3

- ↑ Andreasen NC and Black DW, "Introductory Textbook of Psychiatry." American Psychiatric Publishing Inc. 2006

- ↑ pmhdev. "Oxybutynin (By mouth) - National Library of Medicine - PubMed Health". mmdn/DNX0064. Archived from the original on 2014-02-12. Retrieved 2017-09-02.

- ↑ White AT, Vanhaitsma TA, Vener J, Davis SL (2013). "Effect of passive whole body heating on central conduction and cortical excitability in multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls". J Appl Physiol. 114 (12): 1697–704. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01119.2012. PMC 3680823. PMID 23599395.

- ↑ Allen B. Reitz; Suneel K. Gupta; Yifang Huang; Michael H. Parker; Richard R. Ryan (2007). "The preparation and human muscarinic receptor profiling of oxybutynin and N-desethyloxybutynin enantiomers". Medicinal Chemistry. 3 (6): 543–5. doi:10.2174/157340607782360353. PMID 18045203.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (help) - ↑ Zobrist RH; et al. (2001). "Pharmacokinetics of the R- and S-Enantiomers of Oxybutynin and N-Desethyloxybutynin Following Oral and Transdermal Administration of the Racemate in Healthy Volunteers". Pharmaceutical Research. 18 (7): 1029–1034. doi:10.1023/a:1010956832113.

- ↑ Oki T, et al. (2006). "Advantages for Transdermal over Oral Oxybutynin to Treat Overactive Bladder: Muscarinic Receptor Binding, Plasma Drug Concentration, and Salivary Secretion". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 316 (3): 1137–1145. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.094508. PMID 16282521.

- ↑ Gray, Shelly L.; Anderson, Melissa L. (January 26, 2015). "Cumulative Use of Strong Anticholinergics and Incident Dementia: A Prospective Cohort Study". JAMA Intern. Med. 175 (3): 401–7. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7663. PMC 4358759. PMID 25621434. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ↑ [1] Archived 2017-09-05 at the Wayback Machine "Oxybutynin" Retrieved on 30 August 2012.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Douchamps J, Derenne F, Stockis A, Gangji D, Juvent M, Herchuelz A (1988). "The pharmacokinetics of oxybutynin in man". Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 35 (5): 515–20. doi:10.1007/bf00558247. PMID 3234461.

- ↑ [2][permanent dead link] "Oxybutynin" Retrieved on 30 August 2012.

- ↑ Kachur JF; et al. (1988). "R and S enantiomers of oxybutynin: pharmacological effects in guinea pig bladder and intestine". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 247 (3): 867–72. PMID 2849672.

- ↑ Noronha-Blob L, Kachur JF (1991). "Enantiomers of oxybutynin: in vitro pharmacological characterization at M1, M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors and in vivo effects on urinary bladder contraction, mydriasis and salivary secretion in guinea pigs". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 256 (2): 562–7. PMID 1993995.

- ↑ "DITROPAN®(oxybutynin chloride) Tablets and Syrup" (PDF). FDA. February 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 errors: unsupported parameter

- Webarchive template wayback links

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from March 2018

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with permanently dead external links

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drug has EMA link

- Tertiary alcohols

- Alkyne derivatives

- Diethylamino compounds

- AbbVie brands

- Johnson & Johnson brands

- Carboxylate esters

- Muscarinic antagonists

- RTT