Vemurafenib

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌvɛməˈræfənɪb/ VEM-ə-RAF-ə-nib |

| Trade names | Zelboraf |

| Other names | PLX4032, RG7204, RO5185426 |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | BRAF kinase inhibitor[1] |

| Main uses | Melanoma, Erdheim-Chester disease[2] |

| Side effects | Joint pain, hair loss, itchiness, QT prolongation, tiredness[2] |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth (tablets) |

| Typical dose | 960 mg twice per day[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a612009 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

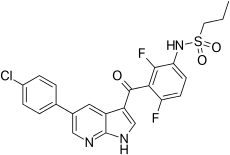

| Formula | C23H18ClF2N3O3S |

| Molar mass | 489.92 g·mol−1 |

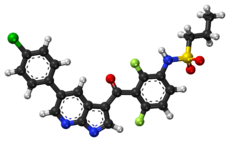

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Vemurafenib, sold under the brand name Zelboraf, is a medication used to treat certain types of late-stage melanoma and Erdheim-Chester disease.[2] Specifically it is used in those with a BRAF V600E mutation.[2] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include joint pain, hair loss, itchiness, QT prolongation, and tiredness.[2] Other side effects may include Dupuytren contracture, sensitivity to radiation therapy, eye inflammation, liver problems, and a new cancer.[2] Use in pregnancy may harm the baby.[2] It works by blocking the b-Raf enzyme.[2]

Vemurafenib was approved for medical use in the United States in 2011 and Europe in 2012.[2][3] In the United Kingdom 56 tablets of 240 mg costs the NHS about £1,750 as of 2021.[1] This amount in the United States costs about 2,650 USD.[4]

Medical uses

It is used for melanoma and some people with Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD), a rare type of histiocytic neoplasm.[5][6]

Dosage

It is generally taken at a dose of 960 mg twice per day.[2] Though smaller doses may be used in those in who side effects are too great.[2]

Side effects

At the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of 960 mg twice a day 31% of patients get skin lesions that may need surgical removal.[7] The BRIM-2 trial investigated 132 patients; the most common adverse events were arthralgia in 58% of patients, skin rash in 52%, and photosensitivity in 52%. In order to better manage side effects some form of dose modification was necessary in 45% of patients. The median daily dose was 1750 mg, 91% of the MTD.[8]

A trial combining vemurafenib and ipilimumab was stopped in April 2013 because of signs of liver toxicity.[9]

-

Papilloma due to vemurafenib

-

Folliculitis due to vemurafenib

-

Sweet disease caused by vemurafenib

Mechanism of action

| vemurafenib | |

|---|---|

| Drug mechanism | |

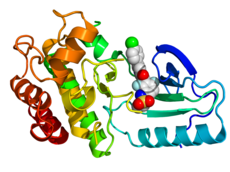

Crystallographic structure of B-Raf (rainbow colored, N-terminus = blue, C-terminus = red) complexed with vemurafenib (spheres, carbon = white, oxygen = red, nitrogen = blue, chlorine = green, fluorine = cyan, sulfur = yellow).[7] | |

| Therapeutic use | melanoma |

| Biological target | BRAF |

| Mechanism of action | protein kinase inhibitor |

| External links | |

| ATC code | L01XE15 |

| PDB ligand id | 032: PDBe, RCSB PDB |

| LIGPLOT | 3og7 |

Vemurafenib causes programmed cell death in melanoma cell lines.[10] Vemurafenib interrupts the B-Raf/MEK step on the B-Raf/MEK/ERK pathway − if the B-Raf has the common V600E mutation.

Vemurafenib only works in melanoma patients whose cancer has a V600E BRAF mutation (that is, at amino acid position number 600 on the B-Raf protein, the normal valine is replaced by glutamic acid).[11] About 60% of melanomas have this mutation. It also has efficacy against the rarer BRAF V600K mutation. Melanoma cells without these mutations are not inhibited by vemurafenib; the drug paradoxically stimulates normal BRAF and may promote tumor growth in such cases.[12][13]

Resistance

Three mechanisms of resistance to vemurafenib (covering 40% of cases) have been discovered:

- Cancer cells begin to overexpress cell surface protein PDGFRB, creating an alternative survival pathway.

- A second oncogene called NRAS mutates, reactivating the normal BRAF survival pathway.[14]

- Stromal cell secretion of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF).[15][16]

Society and culture

Approval

Vemurafenib received FDA approval for the treatment of late-stage melanoma on August 17, 2011,[17] making it the first drug designed using fragment-based lead discovery to gain regulatory approval.[18]

Vemurafenib later received Health Canada approval on February 15, 2012.[19]

On February 20, 2012, the European Commission approved vemurafenib as a monotherapy for the treatment of adult patients with BRAF V600E mutation positive unresectable or metastatic melanoma.[20]

Terminology

The name "vemurafenib" comes from V600E mutated BRAF inhibition.

Research

In a phase I clinical study, vemurafenib (then known as PLX4032) was able to reduce numbers of cancer cells in over half of a group of 16 patients with advanced melanoma. The treated group had a median increased survival time of 6 months over the control group.[21][22][23][24]

A second phase I study, in patients with a V600E mutation in B-Raf, ~80% showed partial to complete regression. The regression lasted from 2 to 18 months.[25]

In early 2010 a Phase I trial[26] for solid tumors (including colorectal cancer), and a phase II study (for metastatic melanoma) were ongoing.[27]

A phase III trial (vs dacarbazine) in patients with previously untreated metastatic melanoma showed an improved rates of overall and progression-free survival.[28]

In June 2011, positive results were reported from the phase III BRIM3 BRAF-mutation melanoma study.[29] The BRIM3 trial reported good updated results in 2012.[30]

Further trials are planned including a trial of vemurafenib co-administered with GDC-0973 (cobimetinib), a MEK-inhibitor.[29] After good results in 2014 the combination was submitted to the EC and FDA for marketing approval.[31]

In January 2015 trial results compared vemurafenib with the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib for metastatic melanoma.[32]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. p. 1062. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 "Vemurafenib Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ↑ "Zelboraf". Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ↑ "Zelboraf Prices, Coupons & Patient Assistance Programs". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the. "Press Announcements - FDA approves first treatment for certain patients with Erdheim–Chester disease, a rare blood cancer". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-04-24. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- ↑ Diamond, Eli L.; Subbiah, Vivek; Lockhart, A. Craig; Blay, Jean-Yves; Puzanov, Igor; Chau, Ian; Raje, Noopur S.; Wolf, Jurgen; Erinjeri, Joseph P. (2018-03-01). "Vemurafenib for BRAF V600-Mutant Erdheim–Chester Disease and Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: Analysis of Data From the Histology-Independent, Phase 2, Open-label VE-BASKET Study". JAMA Oncology. 4 (3): 384–388. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5029. ISSN 2374-2445. PMC 5844839. PMID 29188284.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 PDB: 3OG7; Bollag G, Hirth P, Tsai J, Zhang J, Ibrahim PN, Cho H, Spevak W, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Habets G, et al. (September 2010). "Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma". Nature. 467 (7315): 596–599. Bibcode:2010Natur.467..596B. doi:10.1038/nature09454. PMC 2948082. PMID 20823850.

- ↑ "BRIM-2 Upholds Benefits Emerging with Vemurafenib in Melanoma". Oncology & Biotech News. 5 (7). July 2011. Archived from the original on 2018-07-31. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ↑ "Getting close and personal". The Economist. January 4, 2014. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 2016-04-02. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- ↑ Sala E, Mologni L, Truffa S, Gaetano C, Bollag GE, Gambacorti-Passerini C (May 2008). "BRAF silencing by short hairpin RNA or chemical blockade by PLX4032 leads to different responses in melanoma and thyroid carcinoma cells". Mol. Cancer Res. 6 (5): 751–9. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-2001. PMID 18458053.

- ↑ Maverakis E, Cornelius LA, Bowen GM, Phan T, Patel FB, Fitzmaurice S, He Y, Burrall B, Duong C, Kloxin AM, Sultani H, Wilken R, Martinez SR, Patel F (2015). "Metastatic melanoma - a review of current and future treatment options". Acta Derm Venereol. 95 (5): 516–524. doi:10.2340/00015555-2035. PMID 25520039. Archived from the original on 2018-07-19. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ↑ Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I, Brandhuber BJ, Anderson DJ, Alvarado R, Ludlam MJ, Stokoe D, Gloor SL, Vigers G, Morales T, Aliagas I, Liu B, Sideris S, Hoeflich KP, Jaiswal BS, Seshagiri S, Koeppen H, Belvin M, Friedman LS, Malek S (February 2010). "RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth". Nature. 464 (7287): 431–5. Bibcode:2010Natur.464..431H. doi:10.1038/nature08833. PMID 20130576.

- ↑ Halaban R, Zhang W, Bacchiocchi A, Cheng E, Parisi F, Ariyan S, Krauthammer M, McCusker JP, Kluger Y, Sznol M (February 2010). "PLX4032, a Selective BRAF(V600E) Kinase Inhibitor, Activates the ERK Pathway and Enhances Cell Migration and Proliferation of BRAF(WT) Melanoma Cells". Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 23 (2): 190–200. doi:10.1111/j.1755-148X.2010.00685.x. PMC 2848976. PMID 20149136.

- ↑ Nazarian R, Shi H, Wang Q, Kong X, Koya RC, Lee H, Chen Z, Lee MK, Attar N, Sazegar H, Chodon T, Nelson SF, McArthur G, Sosman JA, Ribas A, Lo RS (November 2010). "Melanomas acquire resistance to B-RAF(V600E) inhibition by RTK or N-RAS upregulation". Nature. 468 (7326): 973–977. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..973N. doi:10.1038/nature09626. PMC 3143360. PMID 21107323. Lay summary – Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-url=(help) - ↑ Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J, Davis A, Mongare MM, Gould J, Frederick DT, Cooper ZA, Chapman PB, Solit DB, Ribas A, Lo RS, Flaherty KT, Ogino S, Wargo JA, Golub TR (July 2012). "Tumour micro-environment elicits innate resistance to RAF inhibitors through HGF secretion". Nature. 487 (7408): 500–4. Bibcode:2012Natur.487..500S. doi:10.1038/nature11183. PMC 3711467. PMID 22763439.

- ↑ Wilson TR, Fridlyand J, Yan Y, Penuel E, Burton L, Chan E, Peng J, Lin E, Wang Y, Sosman J, Ribas A, Li J, Moffat J, Sutherlin DP, Koeppen H, Merchant M, Neve R, Settleman J (July 2012). "Widespread potential for growth-factor-driven resistance to anticancer kinase inhibitors". Nature. 487 (7408): 505–9. Bibcode:2012Natur.487..505W. doi:10.1038/nature11249. PMC 3724525. PMID 22763448.

- ↑ "FDA Approves Zelboraf (Vemurafenib) and Companion Diagnostic for BRAF Mutation-Positive Metastatic Melanoma, a Deadly Form of Skin Cancer" (Press release). Genentech. Archived from the original on 2011-09-24. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ↑ Bollag G, Tsai J, Zhang J, Zhang C, Ibrahim P, Nolop K, Hirth P (November 2012). "Vemurafenib: the first drug approved for BRAF-mutant cancer". Nat Rev Drug Discov. 11 (11): 873–86. doi:10.1038/nrd3847. PMID 23060265. S2CID 9337155.

- ↑ "Notice of Decision for ZELBORAF". Archived from the original on 2012-05-02. Retrieved 2012-04-21.

- ↑ Hofland P (February 20, 2012). "First Personalized Cancer Medicine Allows Patients with Deadly Form of Metastatic Melanoma to Live Significantly Longer". Onco'Zine. The International Cancer Network. Archived from the original on April 11, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Drug hope for advanced melanoma". BBC News. 2009-06-02. Archived from the original on 2009-06-05. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- ↑ Harmon, Amy (2010-02-21). "A Roller Coaster Chase for a Cure". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2017-02-10. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ↑ Garber K (December 2009). "Melanoma drug vindicates targeted approach". Science. 326 (5960): 1619. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1619G. doi:10.1126/science.326.5960.1619. PMID 20019269.

- ↑ Flaherty K. "Phase I study of PLX4032: Proof of concept for V600E BRAF mutation as a therapeutic target in human cancer". 2009 ASCO Annual Meeting Abstract, J Clin Oncol 27:15s, 2009 (suppl; abstr 9000). Archived from the original on 2013-01-27. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ↑ Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, O'Dwyer PJ, Lee RJ, Grippo JF, Nolop K, Chapman PB (August 2010). "Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma". N. Engl. J. Med. 363 (9): 809–19. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. PMC 3724529. PMID 20818844. Lay summary – Corante: In the Pipeline.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-url=(help) - ↑ "Safety Study of PLX4032 in Patients With Solid Tumors". ClinicalTrials.gov. 18 August 2017. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "A Study of RO5185426 in Previously Treated Patients With Metastatic Melanoma". ClinicalTrials.gov. 2010-02-15. Archived from the original on 2011-06-13. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Plexxikon Announces First Patient Dosed in Phase 3 Trial of PLX4032 (RG7204) for Metastatic Melanoma" (Press release). Plexxikon. 2010-01-08. Archived from the original on 2020-12-01. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Plexxikon and Roche Report Positive Data from Phase III BRAF Mutation Melanoma Study". 6 June 2011. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ↑ "Vemurafenib Improves Overall Survival in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma". Archived from the original on 2022-01-11. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ↑ "Cobimetinib at exelixis.com". Archived from the original on 2015-02-04. Retrieved 2015-02-04.

- ↑ "MEK/BRAF Inhibitor Combo Reduces Death by One-Third in Melanoma". 2015. Archived from the original on 2020-11-28. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

Further reading

- Dean L (2017). "Vemurafenib Therapy and BRAF and NRAS Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28809522. Bookshelf ID: NBK447416. Archived from the original on 2020-10-26. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

External links

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- CS1 maint: date format

- CS1 errors: deprecated parameters

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drug has EMA link

- Antineoplastic and immunomodulating drugs

- B-Raf inhibitors

- Chloroarenes

- Fluoroarenes

- Sulfonamides

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- Chemotherapy

- Hoffmann-La Roche brands

- Genentech brands

- Daiichi Sankyo

- RTT