Complications of pregnancy

| Complications of pregnancy | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Severe maternal morbidity (SMM) | |

| |

| As of 2017 about 810 women die daily from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth, with most occuring in low and middle-income countries. | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics |

| Complications | Mother: Postpartum bleeding; high blood pressure of pregnancy, including preeclampsia; gestational diabetes; postpartum depression; postpartum infections; iron-deficiency anemia; hyperemesis gravidarum[1] Baby: Preterm labor, miscarriages, stillbirth, placental abruption[1][2] |

| Deaths | 287,000 maternal deaths (2020)[3] |

Complications of pregnancy are health problems during pregnancy, including those during childbirth and the postpartum period.[2] They include both newly developed and preexisting problems.[2] Those that occur during childbirth are termed labor and delivery complications,[4] while those after childbirth are termed postpartum disorders.[5] While many symptoms of pregnancy, represent expected changes, others require further investigation.[6]

Common types include high blood pressure of pregnancy, including preeclampsia; gestational diabetes; preterm labor, postpartum depression; miscarriage; stillbirth; infections, including during preganc and after delivery; iron-deficiency anemia; and hyperemesis gravidarum.[1][2] Other complications may include blood clots, ectopic pregnancy, placental abruption, and cholestasis of pregnancy.[7][2] Common preexisting problems include epilepsy, asthma, migraines, and thyroid disease.[2] Prenatal tests may be done to prevent or detection certain problems.[2]

Complications of pregnancy, specifically severe maternal morbidity as of 2011, occur in about 1.6% in the United States,[8] and 1.5% in Canada of pregnancies.[9] In 2020 complications resulted in 287,000 maternal deaths globally, with about 95% occurring in the developing world, particularly sub-Saharan Africa.[3] Nearly all women have some problems after childbirth, such as low back pain, breast problems, hemorrhoids, nausea, and tiredness.[10] While health problems after six months are reported by about a third.[11]

Mother

The following problems originate in the mother, however, they may have serious consequences for the baby as well.

Diabetes

Gestational diabetes is when a woman, without a previous diagnosis of diabetes, develops high blood sugar levels during pregnancy.[12][13] There are many non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors that lead to the devopment of this complication. Non-modifiable risk factors include a family history of diabetes, advanced maternal age, and ethnicity. Modifiable risk factors include maternal obesity. There is an elevated demand for insulin during pregnancy which leads to increased insulin production from pancreatic β cells. The elevated demand is a result of increased maternal calorie intake and weight gain, and increased production of prolactin and growth hormone. Gestational diabetes increases risk for further maternal and fetal complications such as development of pre-eclampsia, need for cesarean delivery, preterm delivery, polyhydramnios, macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, fetal hypoglycemia, hyperbilirubinemia, and admission into the neonatal intensive care unit. The increased risk is correlated with the how well the gestational diabetes is controlled during pregnancy with poor control associated with worsened outcomes. A multidisciplinary approach is used to treat gestational diabetes and involves monitoring of blood-glucose levels, nutritional and dietary modifications, lifestyle changes such as increasing physical activity, maternal weight management, and medication such as insulin.[13]

Vomiting

Hyperemesis gravidarum is the presence of severe and persistent vomiting, causing dehydration and weight loss. It is similar although more severe than the common morning sickness.[14][15] It is estimated to affect 0.3–3.6% of pregnant women and is the greatest contributor to hospitalizations under 20 weeks of gestation. Most often, nausea and vomiting symptoms during pregnancy resolve in the first trimester, however, some continue to experience symptoms. Hyperemesis gravidarum is diagnosed by the following criteria: greater than 3 vomiting episodes per day, ketonuria, and weight loss of more than 3 kg or 5% of body weight. There are several non-modifiable and modifiable risk factors that predispose women to development of this condition such as female fetus, psychiatric illness history, high or low BMI pre-pregnancy, young age, African American or Asian ethnicity, type I diabetes, multiple pregnancies, and history of pregnancy affected by hyperemesis gravidarum. There are currently no known mechanisms for the cause of this condition. This complication can cause nutritional deficiency, low pregnancy weight gain, dehydration, and vitamin, electrolyte, and acid-based disturbances in the mother. It has been shown to cause low birth weight, small gestational age, preterm birth, and poor APGAR scores in the infant. Treatments for this condition focus on preventing harm to the fetus while improving symptoms and commonly include fluid replacement and consumption of small, frequent, bland meals. First-line treatments include ginger and acupuncture. Second-line treatments include vitamin B6 +/- doxylamine, antihistamines, dopamine antagonists, and serotonin antagonists. Third-line treatments include corticosteroids, transdermal clonidine, and gabapentin. Treatments chosen are dependent on severity of symptoms and response to therapies.[16]

Pelvic girdle pain

Pelvic girdle pain (PGP) disorder is pain in the area between the posterior iliac crest and gluteal fold beginning peri or postpartum caused by instability and limitation of mobility. It is associated with pubic symphysis pain and sometimes radiation of pain down the hips and thighs. For most pregnant individuals, PGP resolves within three months following delivery, but for some it can last for years, resulting in a reduced tolerance for weight bearing activities. PGP affects around 45% of individuals during pregnancy: 25% report serious pain and 8% are severely disabled.[17][18] Risk factors for complication development include multiparity, increased BMI, physically strenuous work, smoking, distress, history of back and pelvic trauma, and previous history of pelvic and lower back pain. This syndrome results from a growing uterus during pregnancy that causes increased stress on the lumbar and pelvic regions of the mother, thereby, resulting in postural changes and reduced lumbopelvic muscle strength leading to pelvic instability and pain. It is unclear whether specific hormones in pregnancy are associated with complication development. PGP can result in poor quality of life, predisposition to chronic pain syndrome, extended leave from work, and psychosocial distress. Many treatment options are available based on symptom severity. Non-invasive treatment options include activity modification, pelvic support garments, analgesia with or without short periods of bed rest, and physiotherapy to increase strength of gluteal and adductor muscles reducing stress on the lumbar spine. Invasive surgical management is considered a last-line treatment if all other treatment modalities have failed and symptoms are severe.[18]

High blood pressure

Potential severe hypertensive states of pregnancy are mainly:

- Preeclampsia – gestational hypertension, proteinuria (>300 mg), and edema. Severe preeclampsia involves a BP over 160/110 (with additional signs). It affects 5–8% of pregnancies.[19]

- Eclampsia – seizures in a pre-eclamptic patient, affect around 1.4% of pregnancies.[20]

- Gestational hypertension

- HELLP syndrome – Hemolytic anemia, elevated liver enzymes and a low platelet count. Incidence is reported as 0.5–0.9% of all pregnancies.[21]

- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy is sometimes included in the preeclamptic spectrum. It occurs in approximately one in 7,000 to one in 15,000 pregnancies.[22][23]

Blood clots

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT), a form of venous thromboembolism (VTE), has an incidence of 0.5 to 7 per 1,000 pregnancies, and is the second most common cause of maternal death in developed countries after bleeding.[24]

- Caused by: Pregnancy-induced hypercoagulability as a physiological response in preparation for the potential bleeding during childbirth.

- Treatment: Prophylactic treatment, e.g. with low molecular weight heparin may be indicated when there are additional risk factors for deep vein thrombosis.[24]

| Absolute incidence of first VTE per 10,000 person–years during pregnancy and the postpartum period | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swedish data A | Swedish data B | English data | Danish data | |||||

| Time period | N | Rate (95% CI) | N | Rate (95% CI) | N | Rate (95% CI) | N | Rate (95% CI) |

| Outside pregnancy | 1105 | 4.2 (4.0–4.4) | 1015 | 3.8 (?) | 1480 | 3.2 (3.0–3.3) | 2895 | 3.6 (3.4–3.7) |

| Antepartum | 995 | 20.5 (19.2–21.8) | 690 | 14.2 (13.2–15.3) | 156 | 9.9 (8.5–11.6) | 491 | 10.7 (9.7–11.6) |

| Trimester 1 | 207 | 13.6 (11.8–15.5) | 172 | 11.3 (9.7–13.1) | 23 | 4.6 (3.1–7.0) | 61 | 4.1 (3.2–5.2) |

| Trimester 2 | 275 | 17.4 (15.4–19.6) | 178 | 11.2 (9.7–13.0) | 30 | 5.8 (4.1–8.3) | 75 | 5.7 (4.6–7.2) |

| Trimester 3 | 513 | 29.2 (26.8–31.9) | 340 | 19.4 (17.4–21.6) | 103 | 18.2 (15.0–22.1) | 355 | 19.7 (17.7–21.9) |

| Around delivery | 115 | 154.6 (128.8–185.6) | 79 | 106.1 (85.1–132.3) | 34 | 142.8 (102.0–199.8) | –

| |

| Postpartum | 649 | 42.3 (39.2–45.7) | 509 | 33.1 (30.4–36.1) | 135 | 27.4 (23.1–32.4) | 218 | 17.5 (15.3–20.0) |

| Early postpartum | 584 | 75.4 (69.6–81.8) | 460 | 59.3 (54.1–65.0) | 177 | 46.8 (39.1–56.1) | 199 | 30.4 (26.4–35.0) |

| Late postpartum | 65 | 8.5 (7.0–10.9) | 49 | 6.4 (4.9–8.5) | 18 | 7.3 (4.6–11.6) | 319 | 3.2 (1.9–5.0) |

| Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of first VTE during pregnancy and the postpartum period | ||||||||

| Swedish data A | Swedish data B | English data | Danish data | |||||

| Time period | IRR* (95% CI) | IRR* (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI)† | IRR (95% CI)† | ||||

| Outside pregnancy | Reference (i.e., 1.00)

| |||||||

| Antepartum | 5.08 (4.66–5.54) | 3.80 (3.44–4.19) | 3.10 (2.63–3.66) | 2.95 (2.68–3.25) | ||||

| Trimester 1 | 3.42 (2.95–3.98) | 3.04 (2.58–3.56) | 1.46 (0.96–2.20) | 1.12 (0.86–1.45) | ||||

| Trimester 2 | 4.31 (3.78–4.93) | 3.01 (2.56–3.53) | 1.82 (1.27–2.62) | 1.58 (1.24–1.99) | ||||

| Trimester 3 | 7.14 (6.43–7.94) | 5.12 (4.53–5.80) | 5.69 (4.66–6.95) | 5.48 (4.89–6.12) | ||||

| Around delivery | 37.5 (30.9–44.45) | 27.97 (22.24–35.17) | 44.5 (31.68–62.54) | –

| ||||

| Postpartum | 10.21 (9.27–11.25) | 8.72 (7.83–9.70) | 8.54 (7.16–10.19) | 4.85 (4.21–5.57) | ||||

| Early postpartum | 19.27 (16.53–20.21) | 15.62 (14.00–17.45) | 14.61 (12.10–17.67) | 8.44 (7.27–9.75) | ||||

| Late postpartum | 2.06 (1.60–2.64) | 1.69 (1.26–2.25) | 2.29 (1.44–3.65) | 0.89 (0.53–1.39) | ||||

| Notes: Swedish data A = Using any code for VTE regardless of confirmation. Swedish data B = Using only algorithm-confirmed VTE. Early postpartum = First 6 weeks after delivery. Late postpartum = More than 6 weeks after delivery. * = Adjusted for age and calendar year. † = Unadjusted ratio calculated based on the data provided. Source: [25] | ||||||||

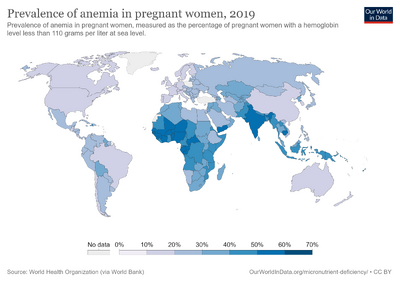

Anemia

Levels of hemoglobin are lower in the third trimesters. According to the United Nations (UN) estimates, approximately half of pregnant individuals develop anemia worldwide. Anemia prevalences during pregnancy differed from 18% in developed countries to 75% in South Asia.[26]

Treatment varies due to the severity of the anaemia, and can be used by increasing iron containing foods, oral iron tablets or by the use of parenteral iron.[12]

Infection

A pregnant woman is more susceptible to certain infections. This increased risk is caused by an increased immune tolerance in pregnancy to prevent an immune reaction against the fetus, as well as secondary to maternal physiological changes including a decrease in respiratory volumes and urinary stasis due to an enlarging uterus.[27] Pregnant individuals are more severely affected by, for example, influenza, hepatitis E, herpes simplex and malaria.[27] The evidence is more limited for coccidioidomycosis, measles, smallpox, and varicella.[27] Mastitis, or inflammation of the breast, occurs in 20% of lactating individuals.[28]

Some infections are vertically transmissible, meaning that they can affect the child as well.

Cardiomyopathy

Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a heart failure caused by a decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) to <45% which occurs towards the end of pregnancy or a few months postpartum. Symptoms include shortness of breath in various positions and/or with exertion, fatigue, pedal edema, and chest tightness. Risk factors associated with the development of this complication include maternal age over 30 years, multi gestational pregnancy, family history of cardiomyopathy, previous diagnosis of cardiomyopathy, pre-eclampsia, hypertension, and African ancestry. The pathogenesis of peripartum cardiomyopathy is not yet known, however, it is suggested that multifactorial potential causes could include autoimmune processes, viral myocarditis, nutritional deficiencies, and maximal cardiovascular changes during which increase cardiac preload. Peripartum cardiomyopathy can lead to many complications such as cardiopulmonary arrest, pulmonary edema, thromboembolisms, brain injury, and death. Treatment of this condition is very similar to treatment of non-gravid heart failure patients, however, safety of the fetus must be prioritized. For example, for anticoagulation due to increased risk for thromboembolism, low molecular weight heparin which is safe for use during pregnancy is used instead of warfarin which crosses the placenta.[29]

Low thyroid

Hypothyroidism (commonly caused by Hashimoto's disease) is an autoimmune disease that affects the thyroid by causing low thyroid hormone levels. Symptoms of hypothyroidism can include low energy, cold intolerance, muscle cramps, constipation, and memory and concentration problems.[30] It is diagnosed by the presence of elevated levels of thyroid stimulation hormone or TSH. People with elevated TSH and decreased levels of free thyroxine or T4 are considered to have overt hypothyroidism. While those with elevated TSH and normal levels of free T4 are considered to have subclinical hypothyroidism.[31] Risk factors for developing hypothyroidism during pregnancy include iodine deficiency, history of thyroid disease, visible goiter, hypothyroidism symptoms, family history of thyroid disease, history of type 1 diabetes or autoimmune conditions, and history of infertility or fetal loss. Various hormones during pregnancy affect the thyroid and increase thyroid hormone demand. For example, during pregnancy, there is increased urinary iodine excretion as well as increased thyroxine binding globulin and thyroid hormone degradation which all increase thyroid hormone demands.[32] This condition can have a profound effect during pregnancy on the mother and fetus. The infant may be seriously affected and have a variety of birth defects. Complications in the mother and fetus can include pre-eclampsia, anemia, miscarriage, low birth weight, still birth, congestive heart failure, impaired neurointellectual development, and if severe, congenital iodine deficiency syndrome.[30][32] This complication is treated by iodine supplementation, levothyroxine which is a form of thyroid hormone replacement, and close monitoring of thyroid function.[32]

Baby

The following problems occur in the baby or placenta, but may have serious consequences on the mother as well.

Ectopic

Ectopic pregnancy is implantation of the embryo outside the uterus

- Caused by: Unknown, but risk factors include smoking, advanced maternal age, and prior surgery, injury, or infection of the fallopian tubes.

- Treatment: May require keyhole surgery to remove the fetus, along with the fallopian tube. If the pregnancy is very early, it may resolve on its own, or it can be treated with methotrexate.[33]

Miscarriage

Miscarriage is the loss of a pregnancy prior to 20 weeks.[34] In the UK, miscarriage is defined as the loss of a pregnancy during the first 23 weeks.[35]

Placental abruption

Placental abruption is the separation of the placenta from the uterus.[12]

- Caused by: Various causes; risk factors include maternal hypertension, trauma, and drug use.

- Treatment: Immediate delivery if the fetus is mature (36 weeks or older), or if a younger fetus or the mother is in distress. In less severe cases with immature fetuses, the situation may be monitored in hospital, with treatment if necessary.

Placenta praevia

Placenta praevia is when the placenta fully or partially covers the cervix.[12]

Placenta accreta

Placenta accreta is an abnormal adherence of the placenta to the uterine wall.[36]

Multiple pregnancies

Multiples may become monochorionic, sharing the same chorion, with resultant risk of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. Monochorionic multiples may even become monoamniotic, sharing the same amniotic sac, resulting in risk of umbilical cord compression and entanglement. In very rare cases, there may be conjoined twins, possibly impairing function of internal organs.

Vertically transmitted infection

The embryo and fetus have little or no immune function. They depend on the immune function of their mother. Several pathogens can cross the placenta and cause (perinatal) infection. Often microorganisms that produce minor illness in the mother are very dangerous for the developing embryo or fetus. This can result in spontaneous abortion or major developmental disorders. For many infections, the baby is more at risk at particular stages of pregnancy. Problems related to perinatal infection are not always directly noticeable.

The term TORCH complex refers to a set of several different infections that may be caused by transplacental infection.

Babies can also become infected by their mother during birth. During birth, babies are exposed to maternal blood and body fluids without the placental barrier intervening and to the maternal genital tract. Because of this, blood-borne microorganisms (hepatitis B, HIV), organisms associated with sexually transmitted disease (e.g., gonorrhoea and chlamydia), and normal fauna of the genito-urinary tract (e.g., Candida) are among those commonly seen in infection of newborns.

Intrauterine bleeding

There have been rare but known cases of intrauterine bleeding caused by injury inflicted by the fetus with its fingernails or toenails.[37]

Risk factors

Factors increasing the risk (to either the pregnant individual, the fetus/es, or both) of pregnancy complications beyond the normal level of risk may be present in the pregnant individual's medical profile either before they become pregnant or during the pregnancy.[38] These pre-existing factors may related to the individual's genetics, physical or mental health, their environment and social issues, or a combination of those.[39]

Biological

Some common biological risk factors include:

- Age of either parent

- Adolescent parents: Young mothers are at an increased risk of developing certain complications, including preterm birth and low infant birth weight.[40]

- Older parents: As they age, both mothers and fathers are at an increased risk for complications in the fetus and during pregnancy and childbirth. Complications for those 45 or older include increased risk of primary Caesarean delivery (i.e. C-section).[41]

- Height: Pregnancy in individuals whose height is less than 1.5 meters (5 feet) correlates with higher incidences of preterm birth and underweight babies. Also, these individuals are more likely to have a small pelvis, which can result in such complications during childbirth as shoulder dystocia.[39]

- Weight

- Low weight: Individuals whose pre-pregnancy weight is less than 45.5 kilograms (100 pounds) are more likely to have underweight babies.

- High weight: Obese individuals are more likely to have very large babies, potentially increasing difficulties in childbirth. Obesity also increases the chances of developing gestational diabetes, high blood pressure, preeclampsia, experiencing postterm pregnancy and requiring a cesarean delivery.[39]

- Pre-existing disease in pregnancy, or an acquired disease: A disease and condition not necessarily directly caused by the pregnancy.

- Risks arising from previous pregnancies: Complications experienced during a previous pregnancy are more likely to recur.[42][43]

- Multiple pregnancies: Individuals who have had greater than five previous pregnancies face increased risks of rapid labor and excessive bleeding after delivery.

- Multiple gestation (having more than one fetus in a single pregnancy): These individuals have an increased risk of mislocated placenta.[39]

Environmental

Some common environmental risk factors during pregnancy include:

- Exposure to environmental toxins

- Exposure to recreational drugs

- Ethanol: Use during pregnancy can cause fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

- Tobacco use: During pregnancy, causes twice the risk of premature rupture of membranes, placental abruption and placenta previa.[45] Also, it increases the odds of the baby being born prematurely by 30%.[46]

- Prenatal cocaine exposure: Associated with premature birth, birth defects and attention deficit disorder.

- Prenatal methamphetamine exposure: Can cause premature birth and congenital abnormalities.[47] Other investigations have revealed short-term neonatal outcomes to include small deficits in infant neurobehavioral function and growth restriction when compared to control infants.[48] Also, prenatal methamphetamine use is believed to have long-term effects in terms of brain development, which may last for many years.[47]

- Cannabis: Possibly associated with adverse effects on the child later in life.

- Social and socioeconomic factors: Generally speaking, unmarried individuals and those in lower socioeconomic groups experience an increased level of risk in pregnancy, due at least in part to lack of access to appropriate prenatal care.[39]

- Unintended pregnancy: Unintended pregnancies preclude preconception care and delays prenatal care. They preclude other preventive care, may disrupt life plans and on average have worse health and psychological outcomes for the mother and, if birth occurs, the child.[49][50]

- Exposure to pharmaceutical drugs:[39] Certain anti-depressants may increase risks of preterm delivery.[51]

High-risk

Some disorders and conditions can mean that pregnancy is considered high-risk (about 6-8% of pregnancies in the USA) and in extreme cases may be contraindicated. High-risk pregnancies are the main focus of doctors specialising in maternal-fetal medicine. Serious pre-existing disorders which can reduce a woman's physical ability to survive pregnancy include a range of congenital defects (that is, conditions with which the woman herself was born, for example, those of the heart or reproductive organs, some of which are listed above) and diseases acquired at any time during the woman's life.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "What are some common complications of pregnancy? | NICHD - Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development". www.nichd.nih.gov. 20 April 2021. Archived from the original on 3 March 2024. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 "Pregnancy complications | Office on Women's Health". www.womenshealth.gov. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Maternal mortality". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ↑ "Introduction to Complications of Labor and Delivery - Women's Health Issues". Merck Manuals Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ↑ "Postpartum Care - Gynecology and Obstetrics". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 4 October 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ↑ "Pregnancy - signs and symptoms". Archived from the original on 17 March 2024. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ↑ "Pregnancy complications". nhs.uk. 8 December 2020. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ↑ "Severe Maternal Morbidity in the United States". CDC. Archived from the original on 2015-06-29. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ "Severe Maternal Morbidity in Canda" (PDF). The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-09. Retrieved 2015-07-08.

- ↑ Cheng, CY; Li, Q (July 2008). "Integrative review of research on general health status and prevalence of common physical health conditions of women after childbirth". Women's health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women's Health. 18 (4): 267–80. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.02.004. PMID 18468922.

- ↑ Borders N (2006). "After the afterbirth: a critical review of postpartum health relative to method of delivery". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 51 (4): 242–48. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2005.10.014. PMID 16814217.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 "Pregnancy complications". womenshealth.gov. 2016-12-14. Archived from the original on 2022-05-31. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lende M, Rijhsinghani A (December 2020). "Gestational Diabetes: Overview with Emphasis on Medical Management". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 17 (24): 9573. doi:10.3390/ijerph17249573. PMC 7767324. PMID 33371325.

- ↑ Summers A (July 2012). "Emergency management of hyperemesis gravidarum". Emergency Nurse. 20 (4): 24–28. doi:10.7748/en2012.07.20.4.24.c9206. PMID 22876404.

- ↑ Goodwin TM (September 2008). "Hyperemesis gravidarum". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 35 (3): viii, 401–17. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2008.04.002. PMID 18760227.

- ↑ Austin, Kerstin; Wilson, Kelley; Saha, Sumona (April 2019). "Hyperemesis Gravidarum". Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 34 (2): 226–241. doi:10.1002/ncp.10205. PMID 30334272. S2CID 52987088.

- ↑ Wu WH, Meijer OG, Uegaki K, Mens JM, van Dieën JH, Wuisman PI, Ostgaard HC (November 2004). "Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain (PPP), I: Terminology, clinical presentation, and prevalence". European Spine Journal. 13 (7): 575–589. doi:10.1007/s00586-003-0615-y. PMC 3476662. PMID 15338362.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Walters, Charlotte; West, Simon; Nippita, Tanya A (2018-07-01). "Pelvic girdle pain in pregnancy". Australian Journal of General Practice. 47 (7): 439–443. doi:10.31128/AJGP-01-18-4467. PMID 30114872. S2CID 52018638. Archived from the original on 2022-07-05. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ↑ Villar J, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, Meraldi M, Lindheimer MD, Betran AP, Piaggio G (2003). "Eclampsia and pre-eclampsia: a health problem for 2000 years.". In Critchly H, MacLean A, Poston L, Walker J (eds.). Pre-eclampsia. London: RCOG Press. pp. 189–207.

- ↑ Abalos E, Cuesta C, Grosso AL, Chou D, Say L (September 2013). "Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 170 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.05.005. PMID 23746796.

- ↑ Haram K, Svendsen E, Abildgaard U (February 2009). "The HELLP syndrome: clinical issues and management. A Review" (PDF). BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 9: 8. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-9-8. PMC 2654858. PMID 19245695. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-11-12.

- ↑ Mjahed K, Charra B, Hamoudi D, Noun M, Barrou L (October 2006). "Acute fatty liver of pregnancy". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 274 (6): 349–53. doi:10.1007/s00404-006-0203-6. PMID 16868757. S2CID 24784165.

- ↑ Reyes H, Sandoval L, Wainstein A, Ribalta J, Donoso S, Smok G, Rosenberg H, Meneses M (January 1994). "Acute fatty liver of pregnancy: a clinical study of 12 episodes in 11 patients". Gut. 35 (1): 101–06. doi:10.1136/gut.35.1.101. PMC 1374642. PMID 8307428.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Venös tromboembolism (VTE) – Guidelines for treatment in C counties. Bengt Wahlström, Emergency department, Uppsala Academic Hospital. January 2008

- ↑ Abdul Sultan A, West J, Stephansson O, Grainge MJ, Tata LJ, Fleming KM, Humes D, Ludvigsson JF (November 2015). "Defining venous thromboembolism and measuring its incidence using Swedish health registries: a nationwide pregnancy cohort study". BMJ Open. 5 (11): e008864. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008864. PMC 4654387. PMID 26560059.

- ↑ Wang S, An L, Cochran SD (2002). "Women". In Detels R, McEwen J, Beaglehole R, Tanaka H (eds.). Oxford Textbook of Public Health (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 1587–601.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Kourtis AP, Read JS, Jamieson DJ (June 2014). "Pregnancy and infection". The New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (23): 2211–18. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1213566. PMC 4459512. PMID 24897084.

- ↑ Kaufmann R, Foxman B (1991). "Mastitis among lactating women: occurrence and risk factors" (PDF). Social Science & Medicine. 33 (6): 701–05. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(91)90024-7. hdl:2027.42/29639. PMID 1957190. Archived from the original on 2022-07-21. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ↑ Davis, Melinda B.; Arany, Zolt; McNamara, Dennis M.; Goland, Sorel; Elkayam, Uri (January 2020). "Peripartum Cardiomyopathy". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 75 (2): 207–221. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.014. PMID 31948651. S2CID 210701262. Archived from the original on 2022-06-23. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Thyroid Disease & Pregnancy | NIDDK". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Archived from the original on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ↑ Sullivan, Scott A. (June 2019). "Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy". Clinical Obstetrics & Gynecology. 62 (2): 308–319. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000432. ISSN 0009-9201. PMID 30985406. S2CID 115198534. Archived from the original on 2022-07-21. Retrieved 2022-06-29.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Taylor, Peter N.; Lazarus, John H. (2019-09-01). "Hypothyroidism in Pregnancy". Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America. Pregnancy and Endocrine Disorders. 48 (3): 547–556. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2019.05.010. ISSN 0889-8529. PMID 31345522. S2CID 71053515.

- ↑ "Ectopic pregnancy – Treatment – NHS Choices". www.nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 2017-08-19. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ↑ "Pregnancy complications". www.womenshealth.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-11-14. Retrieved 2016-11-13.

- ↑ "Miscarriage". NHS Choice. NHS. Archived from the original on 2017-02-15. Retrieved 2017-02-13.

- ↑ Wortman AC, Alexander JM (March 2013). "Placenta accreta, increta, and percreta". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 40 (1): 137–54. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2012.12.002. PMID 23466142.

- ↑ Husemeyer RP, Helme S (1980). "Lacerations of the umbilical cord arteries inflicted by the fetus". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1 (2): 73–74. doi:10.3109/01443618009067348.

- ↑ "Health problems in pregnancy". Medline Plus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2013-08-13.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 Merck. "Risk factors present before pregnancy". Merck Manual Home Health Handbook. Merck Sharp & Dohme. Archived from the original on 2013-06-01.

- ↑ Koniak-Griffin D, Turner-Pluta C (September 2001). "Health risks and psychosocial outcomes of early childbearing: a review of the literature". The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 15 (2): 1–17. doi:10.1097/00005237-200109000-00002. PMID 12095025. S2CID 42701860.

- ↑ Bayrampour H, Heaman M (September 2010). "Advanced maternal age and the risk of cesarean birth: a systematic review". Birth. 37 (3): 219–226. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.2010.00409.x. PMID 20887538.

- ↑ Brouwers L, van der Meiden-van Roest AJ, Savelkoul C, Vogelvang TE, Lely AT, Franx A, van Rijn BB (December 2018). "Recurrence of pre-eclampsia and the risk of future hypertension and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BJOG. 125 (13): 1642–1654. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15394. PMC 6283049. PMID 29978553.

- ↑ Lamont K, Scott NW, Jones GT, Bhattacharya S (June 2015). "Risk of recurrent stillbirth: systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ. 350: h3080. doi:10.1136/bmj.h3080. PMID 26109551.

- ↑ Williams PM, Fletcher S (September 2010). "Health effects of prenatal radiation exposure". American Family Physician. 82 (5): 488–493. PMID 20822083. S2CID 22400308.

- ↑ "Preventing Smoking and Exposure to Secondhand Smoke Before, During, and After Pregnancy" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-11.

- ↑ "Substance Use During Pregnancy". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-10-26.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 "New Mother Fact Sheet: Methamphetamine Use During Pregnancy". North Dakota Department of Health. Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- ↑ Della Grotta S, LaGasse LL, Arria AM, Derauf C, Grant P, Smith LM, Shah R, Huestis M, Liu J, Lester BM (July 2010). "Patterns of methamphetamine use during pregnancy: results from the Infant Development, Environment, and Lifestyle (IDEAL) Study". Maternal and Child Health Journal. 14 (4): 519–27. doi:10.1007/s10995-009-0491-0. PMC 2895902. PMID 19565330.

- ↑ Eisenberg L, Brown SH (1995). The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press. ISBN 978-0-309-05230-6. Retrieved 2011-09-03.

- ↑ "Family Planning - Healthy People 2020". Archived from the original on 2010-12-28. Retrieved 2011-08-18.

- ↑ Gavin AR, Holzman C, Siefert K, Tian Y (2009). "Maternal depressive symptoms, depression, and psychiatric medication use in relation to risk of preterm delivery". Women's Health Issues. 19 (5): 325–34. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2009.05.004. PMC 2839867. PMID 19733802.

External links

| Classification |

|---|