Rabeprazole

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /rəˈbɛprəˌzɔːl/ |

| Trade names | Aciphex, Pariet, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Proton pump inhibitor[1] |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 20 mg[3] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a699060 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 52%[1] |

| Protein binding | 96.3%[4] |

| Metabolism | CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 in the liver[1] |

| Metabolites | thioether carboyxlic acid metabolite, thioether glucuronide metabolite, sulfone metabolite[4] |

| Elimination half-life | ~1 hour[1] |

| Excretion | 90% via kidney as metabolites[5][6] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H21N3O3S |

| Molar mass | 359.44 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture[1] |

| |

| |

Rabeprazole, sold under the brand name Pariet among others, is a medication that decreases stomach acid.[7] It is used to treat peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and excess stomach acid production such as in Zollinger–Ellison syndrome.[7] It may also be used in combination with other medications to treat Helicobacter pylori.[8] Effectiveness is similar to other proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).[9] It is taken by mouth.[7]

Common side effects include constipation, feeling weak, and throat inflammation.[7] Serious side effects may include osteoporosis, low blood magnesium, Clostridium difficile infection, and pneumonia.[7] Use in pregnancy and breastfeeding is of unclear safety.[2] It works by blocking H+/K+-ATPase in the parietal cells of the stomach.[7]

Rabeprazole was patented in 1986, and approved for medical use in 1997.[10] It is available as a generic medication.[8] A month supply of the 20mg/day dose in the United Kingdom costs the NHS GB£1.70 as of 2020.[8] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$11.[11] In 2017, it was the 279th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[12][13]

Medical uses

Rabeprazole, like other proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole, is used for the purposes of gastric acid suppression.[14] This effect is beneficial for the treatment and prevention of conditions in which gastric acid directly worsens symptoms, such as duodenal and gastric ulcers.[14] In the setting of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), whose pathophysiology is characterized by prolonged exposure to gastric acid in the esophagus (often due to changes in stomach and/or esophagus anatomy, such as those induced by abdominal obesity),[15] acid suppression can provide symptomatic relief.[14] Acid suppression is also useful when gastric production of acid is increased, including conditions with excess gastric acid secretion (hypersecretory conditions) like Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, multiple endocrine adenomas, and systemic mastocytosis.[14]

Rabeprazole is also useful alongside antibiotic therapy for the treatment of the pathogen Helicobacter pylori, which otherwise thrives in acidic environments.[14] Notably, H. pylori eradication with antibiotics and rabeprazole was also shown to prevent development of second gastric cancer in a randomized trial in high-risk South Korean patients with early stomach cancer treated by endoscopy.[16]

Thus, rabeprazole is US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved for the treatment of symptomatic GERD in adolescents and adults, healing duodenal ulcers in adults, eradication of Helicobacter pylori, and pathologic hypersecretory conditions.[7] Rabeprazole's may be used to treat symptomatic GERD in adolescents (12 years-old and up).[7]

Geriatrics

Advanced age does not appear to impact rabeprazole's metabolism.[4] However, elevations in the maximum plasma concentration and the total drug exposure (area under the curve, AUC) have occurred.[14]

Kidney or liver problems

In people that have kidney or liver problems, these problems do not appear to affect rabeprazole's metabolism in a meaningful way. This includes individuals on dialysis for kidney problems. Severe liver problems like cirrhosis of the liver do affect rabeprazole's elimination half-life, but not to a degree of dangerous accumulation.[4] In a review of patients taking rabeprazole while having end-stage kidney disease and mild-to-moderate severity, chronic compensated cirrhosis of the liver, the alteration in rabeprazole's metabolism was not clinically meaningful.[1]

Dosage

The only available formulation of rabeprazole is in 20 mg, delayed-release tablets (pictured below).[7] Rabeprazole-based products, like other proton pump inhibitor products, have to be formulated in delayed-release tablets to protect the active medication from being degraded by the acid of the stomach before being absorbed.[1]

The defined daily dose is 20 mg by mouth.[3]

Contraindications

Rabeprazole is contraindicated in the following populations and situations:[7]

- people with a known hypersensitivity to rabeprazole, substituted benzimidazoles (which are chemically similar to rabeprazole, like omeprazole), or any other component of the capsule formulation (e.g. certain dyes)

- concurrent use of rilpivirine, a medication used to treat HIV infection

Hypersensitivity

An allergy to a PPI like rabeprazole may take the form of type I hypersensitivity or delayed hypersensitivity reactions. A selective (pattern C—see below for a discussion of cross-reactivity patterns) type I hypersensitivity reaction to rabeprazole resulting in anaphylaxis has been reported, as well as several whole group hypersentivities.[17]

Hypersensitivity to PPIs can take the form of whole group hypersensitivity, pattern A, B, or C. Whole group hypersentivity occurs when a person is cross-reactive to all PPIs; that is, all PPIs will induce the allergy. In pattern A, a person may be allergic to omeprazole, esomeprazole, and pantoprazole, but not to lansoprazole and rabeprazole. This is thought to be due to the structural similarities between omeprazole, esomeprazole, and pantoprazole, contrasted with lansoprazole and rabeprazole. Pattern B is the opposite, reflecting people that are allergic to lansoprazole and rabeprazole, but not to omeprazole, esomeprazole, and pantoprazole. Pattern C, in the context of rabeprazole, would reflect a person that is allergic to only rabeprazole, but not to other PPIs (omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, and lansoprazole).[17]

Rilpivirine

Rilpivirine, a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor used in the treatment of HIV, is contraindicated with all PPIs because of their acid-suppressing effect. PPIs suppress acid, thereby raising the pH of (alkalizing) the stomach's contents. Rilpivirine is best absorbed under acidic conditions. Therefore, rabeprazole would be expected to decrease the absorption of rilpivirine, decrease the concentration of rilpivirine in the blood, and possibly lead to therapeutic failure and resistance to the medication/class.[18]

Side effects

In general, rabeprazole is fairly well tolerated, even up to five years after clinical trial follow-up.[1] The side effect profile is similar to that of omeprazole.[4] The most common side effects include headache, nausea, and diarrhea.[1] Rare side effects include rashes, flu-like symptoms, and infections (including by the gastrointestinal pathogen Clostridium difficile[19]).[4] Rare instances of rabeprazole-induced liver injury (also known as hepatotoxicity) have been reported. Characteristic proton-pump inhibitor hepatoxicity usually occurs within the first four weeks of starting the medication.[20]

Rabeprazole is associated with elevated serum gastrin levels, which are thought to be dependent upon the degree of CYP2C19 metabolism the drug undergoes. In comparison, rabeprazole is not as significantly metabolized by this enzyme compared to other medications in the same class, like omeprazole.[1] Elevated serum gastrin may be associated with gastric cancer.[21]

Acid suppression via rabeprazole can decrease the absorption of vitamin B12 and magnesium, leading to deficiency.[7]

Very serious side effects have been reported in people taking rabeprazole, but these effects have not been "correlated directly" with the use of rabeprazole.[14] These include Stevens–Johnson syndrome, serious hematological abnormalities, coma, and death.[14] Other possible side effects, common to other PPIs medications in the same class, include bone fractures due to osteoporosis and serious infections with Clostridium difficile.[7]

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Studies using animals models to investigate the likelihood for rabeprazole to cause harm to fetuses have not yet shown evidence of harm, though avoidance of rabeprazole during pregnancy (especially during the critical development period of the first trimester) is considered to be the safest possible route until human studies clarify the exact risk.[14]

It is expected that rabeprazole will be secreted into human breast milk, though the clinical impact of this is still unknown. Avoiding rabeprazole during breastfeeding confers to lowest possible risk.[14]

Overdose

No signs and symptoms have been reported in overdoses of rabeprazole up to 80 mg, but case examples are limited.[22] Notably, rabeprazole has been used in higher doses for the treatment of hypersecretory conditions like Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (up to 120 mg daily).[22]

Animal experiments with ultra-high doses of rabeprazole have demonstrated lethality through unknown mechanisms. The lethal overdose syndrome in animals is characterized by convulsion and coma.[23]

Interactions

Drug-drug

Rabeprazole does not interfere with the plasma concentration of drugs that are also metabolized by the same enzymes (i.e. CYP2C19) that it is metabolized by. Therefore, it is not expected to react with CYP2C19 substrates like theophylline, warfarin, diazepam, and phenytoin.[4] However, the acid-suppression effects of rabeprazole, like other PPIs, may interfere with the absorption of drugs that require acid, such as ketoconazole and digoxin.[14]

There is some evidence that omeprazole and esomeprazole, two medications in the same class as rabeprazole, can disturb the conversion of an anticoagulant medication called clopidogrel to its active metabolite. However, because this is thought to be mediated by the effect of omeprazole and esomeprazole on CYP2C19, the enzyme that activates clopidogrel, this drug interaction is not expected to occur as strongly with rabeprazole. However, whether the effect of omeprazole and esomeprazole on clopidogrel's metabolism actually leads to poor clinical outcomes is still a matter of intense debate among healthcare professionals.[1]

Clinically serious drug-drug interactions may involve the acid-suppression effects of rabeprazole. For example, rabeprazole should not be used concomitantly with rilpivirine, an anti-HIV therapy, which requires acid for absorption. Lowered plasma concentrations of rilpivirine could lead to progression of HIV infection. Other drugs that require acid for absorption include antifungal drugs like ketoconazole and itraconazole, digoxin, iron, mycophenolate, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors like erlotinib, dasatinib, and nilotinib.[7] There is no clinically relevant drug interaction between rabeprazole and antacids.[1][23]

Food-drug

Food does not affect the amount of rabeprazole that enters the body,[1] but it does delay its onset of effect by about 1.7 hours.[4]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Rabeprazole's mechanism of action first involves getting absorbed into the parietal cells of the stomach, which are the cells that are responsible for secreting hydrochloric acid (HCl).[14] At this point, rabeprazole is inactive.[14] However, rabeprazole is then secreted into the secretory canaliculus of the parietal cells, which is the space from which acid secretion occurs.[14] Here, acid secretion is mediated by the energy-dependent acid pumps, called hydrogen potassium adenosine triphosphatase (H+/K+ ATPase) pumps.[14] These enzymatic pumps have cysteine amino acid residues.[14] After being activated by gastric (stomach) acid to a reactive sulfenamide intermediate,[24] rabeprazole permanently binds the cysteine residues, forming covalent, disulfide bonds.[14] This action fundamentally alters the configuration of the acid pump, thereby inhibiting its activity. Thus, acid can no longer be secreted into the gastric lumen (the empty space of the stomach), and the pH of the stomach increases (decrease in the concentration of hydrogen ions, H+).[14] Due to the permanent inhibition of the individual proton pump that each molecule of rabeprazole has bound to, acid secretion is effectively suppressed until new proton pumps are produced by the parietal cells.[20]

Rabeprazole, like other medications in the same class, cannot inhibit the H+/K+ ATPase pumps found in lysosomes, a cellular organelle that degrades biological molecules, because the pumps found in these organelles lack the cysteine residues involved in rabeprazole's mechanism of action.[1]

A unique feature of rabeprazole's mechanism of action in inhibiting acid secretion involves its activation. The pKa (the pH at which 50% of the drug becomes positively charged) of rabeprazole is around 5.0, meaning that it doesn't take a lot of acid to activate it. While this theoretically translates into a faster onset of action for rabeprazole's acid-inhibiting effect, the clinical implications of this fact have yet to be elucidated.[14]

Pharmacokinetics

Rabeprazole's bioavailability is approximately 52%, meaning that 52% of orally administered dose is expected to enter systemic circulation (the bloodstream).[14] Once in the blood, rabeprazole is approximately 96.3%[4]-97%[1] bound to plasma proteins. The biological half-life of rabeprazole in humans is approximately one hour.[1] It takes about 3.5 hours for rabeprazole to reach the maximum concentration in human plasma after a single orally administered dose. Oral absorption is independent of the dose administered.[1]

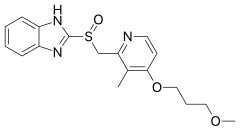

Rabeprazole is extensively metabolized by the liver.[4] 90% of the drug is rendered into metabolites by the liver, which are then excreted by the kidneys.[5] 10% of the dose is excreted in the feces.[1] The drug metabolizing enzymes primarily responsible for rabeprazole's metabolism are CYP2C19 and CYP3A4.[4] However, rabeprazole is mainly metabolized through non-enzymatic reduction to a thioether metabolite.[1] Some of rabeprazole's metabolites include the following: a thioether carboxylic acid metabolite, a thioether glucuronide metabolite, and a sulfone metabolite.[4] The most common metabolites excreted in the urine are the mercapturic acid conjugate and carboxylic acid.[1] A diagram of rabeprazole's phase I metabolism is shown below.[23]

Pharmacogenetics

The effect of rabeprazole may vary based upon the genetics of the individual taking the medication. People may have differences in their capacity to metabolize rabeprazole to an inactive metabolite. This may be mediated through genetic differences in the gene that encodes for the metabolic enzyme CYP2C19. For example, people that are poor CYP2C19 metabolizers (i.e. their version of CYP2C19 is less effective than average) will have trouble metabolizing rabeprazole, allowing the active rabeprazole to stay in the body, where it can exert its effect, longer than intended. Conversely, extensive CYP2C19 metabolizers (i.e. the average metabolic capacity of CYP2C19) will extensively metabolize rabeprazole, as expected. The poor metabolizing CYP2C19 phenotype is found in roughly 3–5% of Caucasian people, and in 17–20% of people of Asian ancestry.[25] In a study on men of Japanese ancestry, this has translated to an average increase of total drug exposure by 50–60% compared to men in the United States.[23] In a study on rabeprazole's pharmacokinetics, the AUC was elevated by approximately 50–60% in men of Japanese ancestry compared to men in the United States.[23]

However, rabeprazole's metabolism is primarily non-enzymatic (it is often inactivated chemically, without the participation of the body's natural drug metabolizing enzymes). Therefore, while a person's CYP2C19 phenotype will affect rabeprazole's metabolism, it is not expected to dramatically affect the efficacy of the medication.[1]

Chemistry

Rabeprazole is classified as a substituted benzimidazole, like omeprazole, lansoprazole, and pantoprazole.[24] Rabeprazole possess properties of both acids and bases, making it an amphotere.[24] The acid dissociation constant (pKa) of the pyridine nitrogen is about equal to 5.[24]

Synthesis

The above synthesis pathway begins with 2,3-dimethypyridine N-oxide (1). Nitration of 2,3-dimethylpyridine N-oxide affords the nitro derivative (the addition of NO2) (2) The newly introduced nitro group is then displaced by the alkoxide from 3-methoxypropanol to yield the corresponding ether (3). Treatment with acetic anhydride results in the Polonovski reaction. Saponification followed by treatment with thionyl chloride then chlorinates the primary alcohol (5). Reaction with benzimidazole-2-thiol (6) followed by oxidation of the resulting thioether to the sulfoxide yields the final product: rabeprazole (8).[26][27]

Physiochemical properties

Rabeprazole is characterized as a white to yellowish-white solid in its pure form. It is soluble in a number of solvents. Rabeprazole is very soluble in water and methanol, freely soluble in ethanol, chloroform, and ethyl acetate, and is insoluble in ether and n-hexane.[23] It is unstable under humid conditions.[1]

History

Rabeprazole was first marketed in Europe in 1998.[1] In 1999, one year later, rabeprazole was approved for use in the United States.[19]

Development

Developed by Eisai Medical Research by the research names E3810 and LY307640, the pre-investigational new drug application was submitted on October 28, 1998. The final investigational new drug application was submitted August 6, 1999. On August 19, 1999, rabeprazole was approved in the US for multiple gastrointestinal indications. The approval for the treatment of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease was on February 12, 2002.[28]

Society and culture

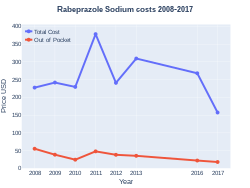

Cost

A month supply in the United Kingdom costs the NHS GB£1.70 as of 2020.[8] In the United States the wholesale cost of this amount is about US$11.[11] In 2017, it was the 279th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than one million prescriptions.[12][13]

-

Rabeprazole costs (US)

-

Rabeprazole prescriptions (US)

Legal status

Rabeprazole is approved in the United States[29] and the United Kingdom[30] for prescription use only. Rabeprazole was approved in India in December 2001.[31] It was approved in Japan in 1997, and in all European Union member countries since.[32]

Brand names

Rabeprazole has been sold in a number of brand names:[33]

| Alphabet | Brand Name |

|---|---|

| A | Acera, Acifix, Acilesol, Aciphex, Acistal, Akirab, Algibra, An Si Fei, Anslag, Antuc, Apt, Aurizol-R |

| B | Bacanero, Barole, Bauzole, Bepra, Bepraz, Berazol, Berizar, Beryx |

| C | Cyra |

| D | Dexicool, Dexpure, Dirab, Domol |

| E | Eurorapi |

| F | Finix, Fodren |

| G | Gastech, Gastrazole, Gastrodine, Gelbra |

| H | Happi, Helirab, Heptadin |

| I | Idizole |

| J | Jelgrad, Ji Nuo |

| K | |

| L | |

| M | Mergium, Monrab |

| N | Neutracaine, Newrabell, Noflux |

| O | Olrite, Ontime, Oppi-R |

| P | Paliell, Paramet, Paricel, Pariet, Pepcia, Pepraz, Ppbest, Praber, Prabex, Prabexol, Prabez, Promto, Puloros |

| Q | |

| R | R-Bit, R-Cid, R-PPI, R-Safe, R.P.Zole, Rabby, Rabe, Rabe-G, Rabeact-20, Rabec, Rabeca, Rabecell, Rabecis, Rabecole, Rabecom, Rabecon, Rabee, Rabefine, Rabegen, Rabekind, Rabelex, Rabelinz, Rabelis, Rabeloc, Rabeman, Rabemed, Rabeol, Rabeone, Rabep, Rabepazole, Rabephex, Rabeprazol, Rabeprazole, Rabeprazolo, Rabeprazolum, Rabesec, Rabestad, Rabetac, Rabetome, Rabetra, Rabetune, Rabeum, Rabex, Rabez, Rabez-FR, Rabezol, Rabezole, Rabibit, Rabicent, Rabicid, Rabicip, Rabifar, Rabifast, Rabilect, Rabip, Rabipot, Rabirol, Rabitab, Rabium, Rabiza, Rabizol, Rablet, Rablet-B, Rabon, Raboz, Rabroz, Rabyprex, Ragi, Ralic, Ramprozole, Raneks, Rap, Rapeed, Rapespes, Rapo, Rapoxol, Rasonix, Razid, Razit, Razo, Razodent, Razogard, Rebacip, Redura, Reorab, Reward, Rifcid, Rodesa, Rolant, Roll, Rowet, Rpraz, Rui Bo te, Rulcer |

| S | Setright, Staycool, Stom, Stomeck |

| T | |

| U | Ulceprazol, Ulcerostate |

| V | Value, Veloz |

| W | Wowrab |

| X | Xin Wei An |

| Y | Yu Tian Qing |

| Z | Zibepar, Zolpras, Zulbex |

| Generic Combination | Brand Name |

|---|---|

| rabeprazole, amoxicillin, clarithromycin | Rabecure, Pylocure |

| rabeprazole, amoxicillin, metronidazole | Rabefine |

| rabeprazole, diclofenac | Drab, Rabin-DFX, Rclonac, Safediclo, Samurai |

| rabeprazole, domperidone | Acera-D, Acistal-D, Adec-R, Algibra-D, Anslag-D, Antuc-DSR, Biorab-DSR, Catrab-DSR, Comvine, Cyclochek, Cyra-D, Dirab-D, Domol-R, Esoga-RD, Gasonil-D, Gastrazole-D, Happi-D, Helirab-D, Kurab-DSR, Lorab-DSR, Neutraflux, Nuloc-D, Olrite-DSR, Parisec-DSR, Pepchek, Pepcia-D, Peraz-D, Ppbest-D, Prazim-RD, Prorab-D, R-Bit-DM, R-Bit-DSR, R-Cid Plus, R-DSR, R-Safe DSR, Rabby-DSR, Rabecis-DSR, Rabecom-D, Rabecon-DSR, Rabee-D, Rabefine-DSR, Rabelex-D, Rabemac-DSR, Rabep-DSR, Rabephex-D, Rabetome-DM, Rabetome-DSR, Rabetune-D, Rabex-D, Rabez-D, Rabi-DSR, Rabibit-D, Rabicent-D, Rabicip-D, Rabifast-DSR, Rabilect-DSR, Rabipot-D, Rabiprime-DSR, Rablet-D, Rabon-D, Rabon-DSR, Rabroz-DSR, Rabter-SR, Raizol-DSR, Rap-D, Rapeed-D, Rapo-DSR, Raz-DSR, Rebilex-DSR, Redoxid, Redura-D, Redura-DSR, Reorab-D, Reorab-DSR, Reward-D, Reward-DSR, Rifcid-D, Rifcid-DSR, Rifkool-DSR, Robilink-D, Rolant-D, Roll-D, Rpraz-D, Rugbi-DM, Rulcer-DSR, Setright-DSR, Sharaz-D, Staycool-DXR, Stomeck-D SR, Ulgo-DSR, Xenorab-DSR, Zolorab-D, Zomitac-DSR, Zorab-D |

| rabeprazole, itopride | Acera-IT, Antuc-IT, Cool Rab-IT, Happi-IT, Itopraz, Itorab, Jeprab-ITO, Pepraz-I, Rabee-ISR, Rabemac-ITR, Rabetome-ISR, Rabez-IT, Rabibit-ISR, Rablet-I, Rablet-IT, Rebilex-ISR, Reorab-IT, Rex-ISR, Rulcer-IT, Veloz-IT, and Zorite |

| rabeprazole, lafutidine | Lafumac Plus |

| rabeprazole, levosulpiride | Happi-L, Lorab-L, Rabekind Plus, Rabicent-L, Rabifast-XL, Rabin-LXR, Rabinta-L, Rabitem-LS, Robiwel-L, Roll-LS, Wokride |

| rabeprazole, ondansetron | Ond-R, Rulcer-ON |

| rabeprazole, polaprezinc | Happi-XT, Rabez-Z |

| rabeprazole, sodium bicarbonate | Pepcia-FF, Raizol |

Research

An alternative formulation of rabeprazole, termed "rabeprazole-ER" (extended release) has been developed. The purpose of the formulation was to increase the half-life of rabeprazole, which normally is very short in humans. Rabeprazole-ER was a 50 mg capsule composed of five non-identical 10 mg tablets that were designed to release rabeprazole at differing intervals throughout the gastrointestinal system. However, because two high quality clinical trials failed to demonstrate a benefit of rabeprazole-ER versus esomeprazole (another common PPI) for healing grade C or D erosive esophagitis, the development of rabeprazole-ER ceased.[34]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 Marelli, Silvia; Pace, Fabio (10 January 2014). "Rabeprazole for the treatment of acid-related disorders". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 6 (4): 423–435. doi:10.1586/egh.12.18. PMID 22928894.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Rabeprazole Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 25 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 January 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 Langtry, HD; Markham, A (October 1999). "Rabeprazole: a review of its use in acid-related gastrointestinal disorders". Drugs. 58 (4): 725–42. doi:10.2165/00003495-199958040-00014. PMID 10551440.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Rabeprazole". PubChem. NCBI. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ↑ PubChem. "Rabeprazole". PubChem. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 "Rabeprazole Sodium Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 13 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 BNF (80 ed.). London: BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

- ↑ "[99] Comparative effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors". Therapeutics Initiative. 28 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Fischer, Jnos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 445. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "NADAC as of 2019-02-27". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Rabeprazole Sodium - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 28 February 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13 14.14 14.15 14.16 14.17 14.18 14.19 Dadabhai, Alia; Friedenberg, Frank K (17 January 2009). "Rabeprazole: a pharmacologic and clinical review for acid-related disorders". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 8 (1): 119–126. doi:10.1517/14740330802622892. PMID 19236223.

- ↑ Chang, Paul; Friedenberg, Frank (March 2014). "Obesity and GERD". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 43 (1): 161–173. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2013.11.009. PMC 3920303. PMID 24503366.

- ↑ Choi IJ, Kook MC, Kim YI, Cho SJ, Lee JY, Kim CG, Park B, Nam BH (March 2018). "Helicobacter pylori Therapy for the Prevention of Metachronous Gastric Cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 378 (12): 1085–1095. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1708423. PMID 29562147.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Lombardo, Carla; Bonadonna, Patrizia (21 March 2015). "Hypersensitivity Reactions to Proton Pump Inhibitors". Current Treatment Options in Allergy. 2 (2): 110–123. doi:10.1007/s40521-015-0046-0.

- ↑ "Edurant" (PDF). Janssen Products. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Aciphex Package Insert" (PDF). Eisai Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Rabeprazole". livertox.nih.gov. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Ahn, Jeong Soo; Eom, Chun-Sick; Jeon, Christie Y; Park, Sang Min (28 April 2013). "Acid suppressive drugs and gastric cancer: A meta-analysis of observational studies". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (16): 2560–2568. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2560. ISSN 1007-9327. PMC 3646149. PMID 23674860.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Rabeprazole – National Library of Medicine HSDB Database". toxnet.nlm.nih.gov. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 "Application Number 20-973/S-009" (PDF). Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 Pilbrant, Ake (1999). "Pharmaceutical considerations". In Olbe, L (ed.). Proton Pump Inhibitors. Proto: Birkhauser. p. 161.

- ↑ "Annotation of FDA Label for rabeprazole and CYP2C19". pharmgkb.org. NIH/NIGMS. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Tagami, K.; Chiku, S.; Sohda, S. (1993). "Synthesis of 14C-labelled sodium pariprazole (E3810)". Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals. 33 (9): 849–852. doi:10.1002/jlcr.2580330908.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 S. Souda et al., EP 268956; eidem, U.S. Patent 5,045,552 (1988, 1991 both to Eisai).

- ↑ "Medical Review and Statistical Review: NDA #21-456" (PDF). www.accessdata.fda.gov. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ↑ "Drugs@FDA". accessdata.fda.gov. US FDA. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Rabeprazole SPC" (PDF). MHRA. 15 January 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2017.

- ↑ "List Of Drugs Approved During 1999". www.cdsco.nic.in. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Archived from the original on 21 December 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ↑ "Aciphex (rabeprazole sodium) Approved For Treatment Of Symptomatic Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) | Evaluate". www.evaluategroup.com. Evaluate Ltd. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 "Rabeprazole international brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ↑ Strand, Daniel S.; Kim, Daejin; Peura, David A. (15 January 2017). "25 Years of Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Comprehensive Review". Gut and Liver. 11 (1): 27–37. doi:10.5009/gnl15502. PMC 5221858. PMID 27840364.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- "Rabeprazole". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Good articles

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to watched fields

- Use dmy dates from January 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Benzimidazoles

- Ethers

- Johnson & Johnson brands

- Janssen Pharmaceutica

- Japanese inventions

- Phenol ethers

- Prodrugs

- Proton pump inhibitors

- Pyridines

- Sulfoxides

- RTT