Carrion's disease

| Carrion's disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Oroya fever | |

| |

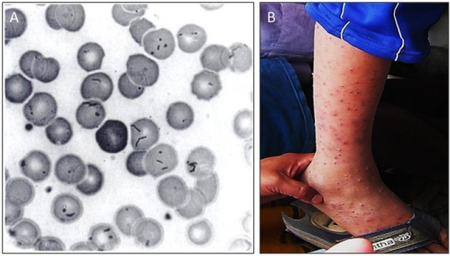

| Carrion's disease chronic phase—verruga peruana (Peruvian warts) | |

Carrion's disease is an infectious disease produced by Bartonella bacilliformis infection.It is named after Daniel Alcides Carrión.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The clinical symptoms of bartonellosis are pleomorphic and some patients from endemic areas may be asymptomatic. The two classical clinical presentations are the acute phase and the chronic phase, corresponding to the two different host cell types invaded by the bacterium (red blood cells and endothelial cells). An individual can be affected by either or both phases.[2][3]

Acute phase

It is also called the hematic phase.[2] The most common findings are fever (usually sustained, but with temperature no greater than 102 °F (39 °C)), pale appearance, malaise, painless liver enlargement, jaundice, enlarged lymph nodes, and enlarged spleen. This phase is characterized by severe hemolytic anemia and transient immunosuppression. The case fatality ratios of untreated patients exceeded 40% but reach around 90% when opportunistic infection with Salmonella spp. occurs. In a recent study, the attack rate was 13.8% (123 cases) and the case-fatality rate was 0.7%.[citation needed]

Other symptoms include a headache, muscle aches, and general abdominal pain.[4] Some studies have suggested a link between Carrion's disease and heart murmurs due to the disease's impact on the circulatory system. In children, symptoms of anorexia, nausea, and vomiting have been investigated as possible symptoms of the disease.[2]

Most of the mortality of Carrion's disease occurs during the acute phase. Studies vary in their estimates of mortality. In one study, mortality has been estimated as low as just 1% in studies of hospitalized patients, to as high as 88% in untreated, unhospitalized patients.[2] In developed countries, where the disease rarely occurs, it is recommended to seek the advice of a specialist in infectious disease when diagnosed.[5] Mortality is often thought to be due to subsequent infections due to the weakened immune symptoms and opportunistic pathogen invasion, or consequences of malnutrition due to weight loss in children.[2][6] In a study focusing on pediatric and gestational effects of the disease, mortality rates for pregnant women with the acute phase were estimated at 40% and rates of spontaneous abortion in another 40%.[2]

Chronic phase

It is also called the eruptive phase or tissue phase, in which the patients develop a cutaneous rash produced by a proliferation of endothelial cells and is known as "Peruvian warts" or "verruga peruana". Depending on the size and characteristics of the lesions, there are three types: miliary (1–4 mm), nodular or subdermic, and mular (>5mm). Miliary lesions are the most common. The lesions often ulcerate and bleed.[4]

The most common findings are bleeding of verrugas, fever, malaise, arthralgias (joint pain), anorexia, myalgias, pallor, lymphadenopathy, and liver and spleen enlargement.

On microscopic examination, the chronic phase and its rash are produced by angioblastic hyperplasia, or the increased rates and volume of cell growth in the tissues that form blood vessels. This results in a loss of contact between cells and a loss of normal functioning.[2][7]

The chronic phase is the more common phase. Mortality during the chronic phase is very low.[2][4]

Cause

Carrion's disease is caused by Bartonella bacilliformis.[4][7] Recent investigations show that Candidatus Bartonella ancashi may cause verruga peruana, although it may not meet all of Koch's postulates. There has been no experimental reproduction of the Peruvian wart in animals and there is little research on the disease's natural spread or impact in native animals.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis during the acute phase can be made by obtaining a peripheral blood smear with Giemsa stain, Columbia blood agar cultures, immunoblot, indirect immunofluorescence, and PCR. Diagnosis during the chronic phase can be made using a Warthin-Starry stain of wart biopsy, PCR, and immunoblot.

Treatment

Because Carrion's disease is often comorbid with Salmonella infections, chloramphenicol has historically been the treatment of choice.[5]

Fluoroquinolones (such as ciprofloxacin) or chloramphenicol in adults and chloramphenicol plus beta-lactams in children are the antibiotic regimens of choice during the acute phase of Carrion's disease.[5] Chloramphenicol-resistant B. bacilliformis has been observed.[2][5]

During the eruptive phase, in which chloramphenicol is not useful, azithromycin, erythromycin, and ciprofloxacin have been used successfully for treatment. Rifampin or macrolides are also used to treat both adults and children.[2][5]

Because of the high rates of comorbid infections and conditions, multiple treatments are often required. These have included the use of corticosteroids for respiratory distress, red blood cell transfusions for anemia, pericardiectomies for pericardial tamponades, and other standard treatments.[2][8]

References

- ↑ synd/3112 at Who Named It?

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Huarcaya, Erick; Maguiña, Ciro; Torres, Rita; Rupay, Joan; Fuentes, Luis (2004-10-01). "Bartonelosis (Carrion's Disease) in the pediatric population of Peru: an overview and update". Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 8 (5): 331–339. doi:10.1590/S1413-86702004000500001. ISSN 1413-8670. PMID 15798808.

- ↑ "Carrion's disease - RightDiagnosis.com". www.rightdiagnosis.com. Archived from the original on 2018-12-09. Retrieved 2016-11-02.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "Bartonella Infection (Cat Scratch Disease, Trench Fever, and Carrión's Disease)". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2019-05-07. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Bartonellosis - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders)". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- ↑ Maguina C, Garcia PJ, Gotuzzo E, Cordero L, Spach DH (September 2001). "Bartonellosis (Carrión's disease) in the modern era". Clin. Infect. Dis. 33 (6): 772–779. doi:10.1086/322614. PMID 11512081.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Maco V, Maguiña C, Tirado A, Maco V, Vidal JE (2004). "Carrion's disease (Bartonellosis bacilliformis) confirmed by histopathology in the High Forest of Peru". Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo. 46 (3): 171–174. doi:10.1590/S0036-46652004000300010. PMID 15286824.

- ↑ Camacho, Cesar Henriquez (7 December 2002). "Human Bartonellosis Cause By Bartonella Bacilliformis". University of Pittsburgh. University of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on 10 August 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

| Classification |

|---|