Q fever

| Q fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Coxiellosis[1][2] | |

| |

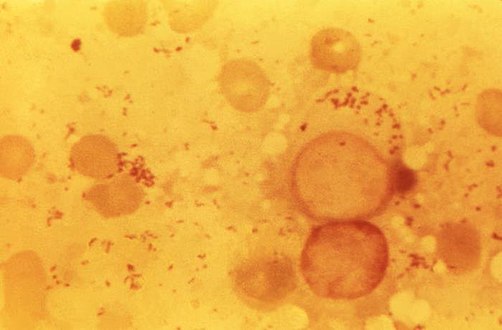

| Immunohistochemical detection of C. burnetii in resected cardiac valve of a 60-year-old man with Q fever endocarditis, Cayenne, French Guiana: Monoclonal antibodies against C. burnetii and hematoxylin were used for staining; original magnification is ×50. | |

| Symptoms | Fever, severe headache, muscle pain, joint pain, loss of appetite, upper respiratory problems, dry cough, pleuritic pain, chills, confusion, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.[3] |

| Complications | Pneumonia, hepatitis, uveitis, myocarditis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis[4] |

| Usual onset | Suddenly 2 to 4 weeks after exposure[4] |

| Types | Acute, chronic[1] |

| Risk factors | Contact with livestock[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Immunofluorescence assay[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Pneumonia, influenza, brucellosis, leptospirosis, meningitis, viral hepatitis, dengue fever, malaria, other rickettsial infections[2] |

| Prevention | Vaccine[5] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics[6] |

Q fever or query fever is a bacterial infection caused by Coxiella burnetii.[1] Signs and symptoms typically begin 2 to 4 weeks after exposure and include fever and flu-like symptoms with aching muscles and headache.[4] Complications include pneumonia, hepatitis, and later may result in uveitis, myocarditis, endocarditis or osteomyelitis.[4] Infection in pregnancy may result in death of the baby.[4]

It affects humans and other animals. This organism is uncommon, but may be found in cattle, sheep, goats, and other domestic mammals, including cats and dogs. The infection results from inhalation of a spore-like small-cell variant, and from contact with the milk, urine, feces, vaginal mucus, or semen of infected animals. Rarely, the disease is tick-borne.[7] Humans are vulnerable to Q fever, and infection can result from even a few organisms.[7] The bacterium is an obligate intracellular pathogenic parasite[8] Diagnosis is by immunofluorescence assay.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Incubation period is usually two to four weeks.[4] The most common manifestation is flu-like symptoms: abrupt onset of fever, malaise, profuse perspiration, severe headache, muscle pain, joint pain, loss of appetite, upper respiratory problems, dry cough, pleuritic pain, chills, confusion, and gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. About half of infected individuals exhibit no symptoms.[3]

During its course, the disease can progress to an atypical pneumonia, which can result in a life-threatening acute respiratory distress syndrome, whereby such symptoms usually occur during the first four to five days of infection.[6]

Less often, Q fever causes (granulomatous) hepatitis, which may be asymptomatic or become symptomatic with malaise, fever, liver enlargement, and pain in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Whereas transaminase values are often elevated, jaundice is uncommon. Retinal vasculitis is a rare manifestation of Q fever.[9]

The chronic form of Q fever is virtually identical to endocarditis (i.e. inflammation of the inner lining of the heart), which can occur some time following the infection. It is usually fatal if untreated. However, with appropriate treatment, the mortality falls to around 10%.[10][11]

Cause

-

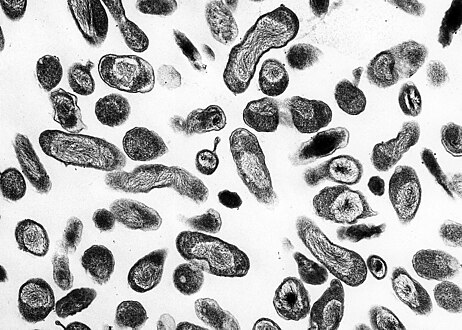

This photomicrograph of an unknown tissue sample, revealed the presence of numerous, Gram-negative, Coxiella burnetii bacteria, which are the pathogens responsible for causing the disease, Q fever

-

C. burnetii, the Q fever-causing agent

-

A dry fracture of a Vero cell exposing the contents of a vacuole where Coxiella burnetii are busy growing

In terms of the cause of Q fever, is due to the bacterium Coxiella burnetii. the risk of contracting the infection comes from dogs, cats, cattle, sheep and goats and therefore the mode is via infected animals (milk, urine, feces)[12][13][14]

Pathophysiology

The bacteria use a type IVB secretion system known as Icm/Dot (intracellular multiplication / defect in organelle trafficking genes) to inject over 100 effector proteins into the host. These effectors increase the bacteria's ability to survive and grow inside the host cell by modulating many host cell pathways, including blocking cell death, inhibiting immune reactions, and altering vesicle trafficking.[15][16][17] In Legionella pneumophila, which uses the same secretion system and also injects effectors, survival is enhanced because these proteins interfere with fusion of the bacteria-containing vacuole with the host's degradation endosomes.[18]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually based on serology[19][20] (looking for an antibody response) rather than looking for the organism itself. Serology allows the detection of chronic infection by the appearance of high levels of the antibody against the virulent form of the bacterium. Molecular detection of bacterial DNA is increasingly used. Contrary to most obligate intracellular parasites, Coxiella burnetii can be grown in an axenic culture, but its culture is technically difficult and not routinely available in most microbiology laboratories.[21]

Q fever can cause endocarditis (infection of the heart valves) which may require transoesophageal echocardiography to diagnose. Q fever hepatitis manifests as an elevation of alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase, but a definitive diagnosis is only possible on liver biopsy, which shows the characteristic fibrin ring granulomas.[22]

Prevention

Research done in the 1960s–1970s by French Canadian-American microbiologist and virologist Paul Fiset was instrumental in the development of the first successful Q fever vaccine.[23]

Protection is offered by Q-Vax, a whole-cell, inactivated vaccine developed by an Australian vaccine manufacturing company, CSL Limited.[5] The intradermal vaccination is composed of killed C. burnetii organisms. Skin and blood tests should be done before vaccination to identify pre-existing immunity, because vaccinating people who already have an immunity can result in a severe local reaction. After a single dose of vaccine, protective immunity lasts for many years. Revaccination is not generally required. Annual screening is typically recommended.[24]

In 2001, Australia introduced a national Q fever vaccination program for people working in “at risk” occupations. Vaccinated or previously exposed people may have their status recorded on the Australian Q Fever Register,[25] which may be a condition of employment in the meat processing industry or in veterinary research.[26]

Preliminary results suggest vaccination of animals may be a method of control. Published trials proved that use of a registered phase vaccine (Coxevac) on infected farms is a tool of major interest to manage or prevent early or late abortion, repeat breeding, anoestrus, silent oestrus, metritis, and decreases in milk yield when C. burnetii is the major cause of these problems.[27][28]

Treatment

Treatment of acute Q fever with antibiotics is very effective and should be given in consultation with an infectious diseases specialist.[6][29]

Commonly used antibiotics include doxycycline, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and hydroxychloroquine.[6] Chronic Q fever is more difficult to treat and can require up to four years of treatment with doxycycline and quinolones or doxycycline with hydroxychloroquine.[6]

If a person has Chronic Q fever, doxycycline and hydroxychloroquine will be prescribed for at least eighteen months. Q fever in pregnancy is especially difficult to treat because doxycycline and ciprofloxacin are contraindicated in pregnancy. The preferred treatment for pregnancy and children under the age of eight is co-trimoxazole.[30] [31]

Epidemiology

The pathogenic agent is found worldwide, with the exception of New Zealand.[32] The bacterium is extremely sustainable and virulent: a single organism is able to cause an infection. The common source of infection is the inhalation of contaminated dust, contact with contaminated milk, meat, or wool, and particularly birthing products. Ticks can transfer the pathogenic agent to other animals. Transfer between humans seems extremely rare and has so far been described in very few cases.[33][34]

Some studies have shown more men to be affected than women,[35][36] which may be attributed to different employment rates in typical professions.[37] “At risk” occupations include:[38]

- Veterinary personnel

- Stockyard workers

- Farmers

- Sheep shearers

- Animal transporters

- Laboratory workers handling potentially infected veterinary samples or visiting abattoirs

- Hide (tannery) workers

History

Q fever was first described in 1935 by Edward Holbrook Derrick[39] in slaughterhouse workers in Brisbane, Queensland. The "Q" stands for "query" and was applied at a time when the causative agent was unknown; it was chosen over suggestions of abattoir fever and Queensland rickettsial fever, to avoid directing negative connotations at either the cattle industry or the state of Queensland.[40]

The pathogen of Q fever was discovered in 1937, when Frank Macfarlane Burnet and Mavis Freeman isolated the bacterium from one of Derrick's patients.[41]

It was originally identified as a species of Rickettsia. H.R. Cox and Gordon Davis elucidated the transmission when they isolated it from ticks found in the US state of Montana in 1938.[42] It is a zoonotic disease whose most common animal reservoirs are cattle, sheep, and goats. Coxiella burnetii – named for Cox and Burnet – is regarded as similar to Legionella and Francisella, and is a proteobacterium.[33][43][44]

Society and culture

An early mention of Q fever was important in one of the early Dr. Kildare films (1939, Calling Dr. Kildare). Kildare's mentor Dr. Gillespie (Lionel Barrymore) tires of his protégé working fruitlessly on "exotic diagnoses" ("I think it's Q fever!") and sends him to work in a neighborhood clinic, instead.[45][46]

Biological warfare

C. burnetii has been used to develop biological weapons.[47]The United States investigated it as a potential biological warfare agent in the 1950s, with eventual standardization as agent OU. At Fort Detrick and Dugway Proving Ground, human trials were conducted on Whitecoat volunteers to determine the median infective dose (18 MICLD50/person i.h.) and course of infection. The Deseret Test Center dispensed biological Agent OU with ships and aircraft, during Project 112 and Project SHAD.[48]

C. burnetii is currently ranked as a "category B" bioterrorism agent by the CDC.[49] It can be contagious, and is very stable in aerosols in a wide range of temperatures. Q fever microorganisms may survive on surfaces up to 60 days. [50]

Other animals

Cattle, goats, and sheep are most commonly infected, and can serve as a reservoir for the bacteria. Q fever is a well-recognized cause of abortions in ruminants and pets. C. burnetii infection in dairy cattle has been well documented and its association with reproductive problems in these animals has been reported in Canada, the US, Cyprus, France, Hungary, Japan, Switzerland, and Germany.[51] For instance, in a study published in 2008,[52] a significant association has been shown between the seropositivity of herds and the appearance of typical clinical signs of Q fever, such as abortion, stillbirth, weak calves, and repeat breeding. Moreover, experimental inoculation of C. burnetii in cattle induced not only respiratory disorders and cardiac failures (myocarditis), but also frequent abortions and irregular repeat breedings.[53]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Epidemiology and Statistics | Q Fever | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-09-16. Archived from the original on 2011-05-28. Retrieved 2020-05-27.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Disorders, National Organization for Rare (2003). "Q Fever". NORD Guide to Rare Disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-7817-3063-1. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Anderson, Alicia; McQuiston, Jennifer (2011). "Q Fever". In Brunette, Gary W.; et al. (eds.). CDC Health Information for International Travel: The Yellow Book. Oxford University Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-19-976901-8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Barlow, Gavin; Irving, William L.; Moss, Peter J. (2020). "20. Infectious disease". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 548–549. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2023-01-15. Retrieved 2023-01-14.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Q fever Vaccine" (PDF). CSL. 17 January 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Coxiella/Q Fever". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Q Fever | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2017-12-27. Archived from the original on 2011-06-17. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ Shannon, Jeffrey G.; Heinzen, Robert A. (2009). "Adaptive immunity to the obligate intracellular pathogen Coxiella burnetii". Immunologic Research. 43 (1–3): 138–148. doi:10.1007/s12026-008-8059-4. ISSN 0257-277X. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 25 September 2022.

- ↑ Kuhne, F; Morlat, P; Riss, I; Dominguez, M; Hostyn, P; Carniel, N; Paix, MA; Aubertin, J; Raoult, D; Le Rebeller, MJ (1992). "La vascularite A29, B12, est-elle déclenchée par l'agent de la fièvre Q? (Coxiella burnetii)" [Is A29, B12 vasculitis caused by the Q fever agent? (Coxiella burnetii)]. Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie (in français). 15 (5): 315–321. OCLC 116712679. PMID 1430809.

- ↑ Karakousis PC, Trucksis M, Dumler JS (June 2006). "Chronic Q Fever in the United States". J. Clin. Microbiol. 44 (6): 2283–7. doi:10.1128/JCM.02365-05. PMC 1489455. PMID 16757641.

- ↑ "Q fever". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ↑ "Q fever". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ↑ Beare PA, Samuel JE, Howe D, Virtaneva K, Porcella SF, Heinzen RA (April 2006). "Genetic diversity of the Q Fever agent, Coxiella burnetii, assessed by microarray-based whole-genome comparisons". J. Bacteriol. 188 (7): 2309–2324. doi:10.1128/JB.188.7.2309-2324.2006. PMC 1428397. PMID 16547017.

- ↑ "Q fever | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-12-31. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ Lührmann A, Nogueira CV, Carey KL, Roy CR (November 2010). "Inhibition of pathogen-induced apoptosis by a Coxiella burnetii type IV effector protein". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (44): 18997–9001. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10718997L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1004380107. PMC 2973885. PMID 20944063.

- ↑ Clemente TM, Mulye M, Justis AV, Nallandhighal S, Tran TM, Gilk SD (October 2018). Freitag NE (ed.). "Coxiella burnetii Blocks Intracellular Interleukin-17 Signaling in Macrophages". Infection and Immunity. 86 (10). doi:10.1128/IAI.00532-18. PMC 6204741. PMID 30061378.

- ↑ Newton HJ, Kohler LJ, McDonough JA, Temoche-Diaz M, Crabill E, Hartland EL, Roy CR (July 2014). Valdivia RH (ed.). "A screen of Coxiella burnetii mutants reveals important roles for Dot/Icm effectors and host autophagy in vacuole biogenesis". PLOS Pathogens. 10 (7): e1004286. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004286. PMC 4117601. PMID 25080348.

- ↑ Pan X, Lührmann A, Satoh A, Laskowski-Arce MA, Roy CR (June 2008). "Ankyrin repeat proteins comprise a diverse family of bacterial type IV effectors". Science. 320 (5883): 1651–4. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1651P. doi:10.1126/science.1158160. PMC 2514061. PMID 18566289.

- ↑ Maurin M, Raoult D (October 1999). "Q fever". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12 (4): 518–53. doi:10.1128/CMR.12.4.518. PMC 88923. PMID 10515901.

- ↑ Scola BL (October 2002). "Current laboratory diagnosis of Q Fever". Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 13 (4): 257–262. doi:10.1053/spid.2002.127199. PMID 12491231.

- ↑ Omsland A, Cockrell DC, Howe D, Fischer ER, Virtaneva K, Sturdevant DE, Porcella SF, Heinzen RA (March 17, 2009). "Host cell-free growth of the Q fever bacterium Coxiella burnetii". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 106 (11): 4430–4. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.4430O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812074106. PMC 2657411. PMID 19246385.

- ↑ van de Veerdonk FL, Schneeberger PM (2006). "Patient with fever and diarrea". Clin Infect Dis. 42 (7): 1051–2. doi:10.1086/501027.

- ↑ Saxon, Wolfgang (March 8, 2001). "Dr. Paul Fiset, 78, Microbiologist And Developer of Q Fever Vaccine". New York Times. p. C-17. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ↑ "USCF communicable disease prevention program animal exposure surveillance program" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ "Australian Q Fever Register". AusVet. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑ Mckenzie, Bex (2019-11-20). "Q-Fever Vaccinations". Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences. Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ↑ Camuset, P; Remmy, D (2008). "Q Fever (Coxiella burnetii) Eradication in a Dairy Herd by Using Vaccination with a Phase 1 Vaccine". Budapest: XXV World Buiatrics Congress.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Hogerwerf, L; Van Den Brom, R; Roest, HI; Bouma, A; Vellema, P; Pieterse, M; Dercksen, D; Nielen, M (2011). "Reduction of Coxiella burnetii prevalence by vaccination of goats and sheep, the Netherlands". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (3): 379–386. doi:10.3201/eid1703.101157. PMC 3166012. PMID 21392427.

- ↑ "Treatment of Q fever | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 January 2019. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ Carcopino X, Raoult D, Bretelle F, Boubli L, Stein A (2007). "Managing Q fever during pregnancy: The benefits of long-term Cotrimoxazole therapy". Clin Infect Dis. 45 (5): 548–555. doi:10.1086/520661. PMID 17682987.

- ↑ "Query Fever - MARI REF". mariref.com. 20 July 2021. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ↑ Cutler SJ, Bouzid M, Cutler RR (April 2007). "Q fever". J. Infect. 54 (4): 313–8. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2006.10.048. PMID 17147957.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Patil, Sachin M.; Regunath, Hariharan (2022). "Q Fever". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- ↑ "Q fever home | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 January 2019. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ↑ Domingo P, Muñoz C, Franquet T, Gurguí M, Sancho F, Vazquez G (October 1999). "Acute Q fever in adult patients: report on 63 sporadic cases in an urban area". Clin. Infect. Dis. 29 (4): 874–9. doi:10.1086/520452. PMID 10589906.

- ↑ Dupuis G, Petite J, Péter O, Vouilloz M (June 1987). "An important outbreak of human Q fever in a Swiss Alpine valley". Int J Epidemiol. 16 (2): 282–7. doi:10.1093/ije/16.2.282. PMID 3301708.

- ↑ "Q fever". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID), Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (DVBD). Archived from the original on 28 May 2011. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ "Q fever: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-04-18. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ Derrick, E. H. (August 1937). "'Q' Fever a new fever entity: clinical features. diagnosis, and laboratory investigation". Medical Journal of Australia. 2 (8): 281–299. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1937.tb43743.x.

- ↑ Joseph E. McDade (1990). "Historical aspects of Q Fever". In Thomas J. Marrie (ed.). Q Fever, Volume I: The Disease. CRC Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-8493-5984-2.

- ↑ Burnet, F. M.; Freeman, M. (1 July 1983). "Experimental Studies on the Virus of 'Q' Fever". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 5 (4): 800–808. doi:10.1093/clinids/5.4.800. PMID 6194551.

- ↑ Davis, Gordon E.; Cox, Herald R.; Parker, R. R.; Dyer, R. E. (1938). "A Filter-Passing Infectious Agent Isolated from Ticks". Public Health Reports. 53 (52): 2259. doi:10.2307/4582746. JSTOR 4582746.

- ↑ "Coxiella burnetii - Volume 14, Number 10—October 2008 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC". CDC. doi:10.3201/eid1410.e11410. Archived from the original on 26 March 2021. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ↑ Honarmand, Hamidreza (19 November 2012). "Q Fever: An Old but Still a Poorly Understood Disease". Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Infectious Diseases. 2012: e131932. doi:10.1155/2012/131932. ISSN 1687-708X. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ↑ "Calling Dr. Kildare". Movie Mirrors Index. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ↑ Kalisch, Philip A; Kalisch, Beatrice J (September 1985). "When Americans called for Dr. Kildare: images of physicians and nurses in the Dr. Kildare and Dr. Gillespie movies, 1937-1947" (PDF). Medical Heritage. 1 (5): 348–363. PMID 11616027. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-03-03. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

- ↑ Madariaga MG, Rezai K, Trenholme GM, Weinstein RA (November 2003). "Q Fever: A biological weapon in your backyard". Lancet Infect Dis. 3 (11): 709–21. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00804-1. PMID 14592601.

- ↑ Deseret Test Center, Project SHAD, Shady Grove revised fact sheet[permanent dead link]

- ↑ Seshadri R, Paulsen IT, Eisen JA, et al. (April 2003). "Complete genome sequence of the Q-fever pathogen Coxiella burnetii". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (9): 5455–60. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.5455S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0931379100. PMC 154366. PMID 12704232.

- ↑ Williams, Mollie; Armstrong, Lisa; Sizemore, Daniel C. (2022). "Biologic, Chemical, and Radiation Terrorism Review". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- ↑ To, Ho; Sakai, Ritsuko; Shirota, Kazutoshi; Kano, Chiaki; Abe, Satomi; Sugimoto, Tomoaki; Takehara, Kazuaki; Morita, Chiharu; Takashima, Ikuo; Maruyama, Tsutomu; Yamaguchi, Tsuyoshi; Fukushi, Hideto; Hirai, Katsuya (April 1998). "Coxiellosis in domestic and wild birds from Japan". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 34 (2): 310–316. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-34.2.310. PMID 9577778. S2CID 36217068.

- ↑ Czaplicki, Guy; Houtain, Jean-Yves; Mullender, Cédric; Porter, Sarah Rebecca; Humblet, Marie-France; Manteca, Christophe; Saegerman, Claude (June 2012). "Apparent prevalence of antibodies to Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) in bulk tank milk from dairy herds in southern Belgium". The Veterinary Journal. 192 (3): 529–531. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.08.033. hdl:2268/103290. PMID 21962829.

- ↑ Plommet, M; Capponi, M; Gestin, J; Renoux, G (1973). "Fièvre Q expérimentale des bovins" [Experimental Q fever in cattle]. Annales de Recherches Vétérinaires (in français). 4 (2): 325–346. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2021-10-06.

External links

- Q fever Archived 2021-05-06 at the Wayback Machine at the CDC

- Coxiella burnetii genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID Archived 2021-08-26 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 français-language sources (fr)

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from September 2022

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with permanently dead external links

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Atypical pneumonias

- Bacterial diseases

- Bacterium-related cutaneous conditions

- Biological weapons

- Bovine diseases

- Rare infectious diseases

- Rodent-carried diseases

- Sheep and goat diseases

- Tick-borne diseases

- Zoonoses

- Zoonotic bacterial diseases