Escherichia coli O104:H4

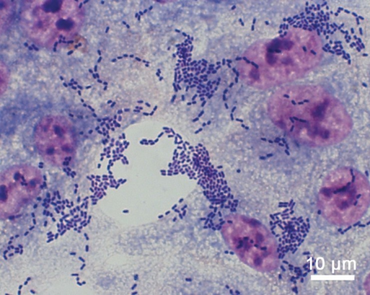

Escherichia coli O104:H4 is an enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strain of the bacterium Escherichia coli, and the cause of the 2011 Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak.[1] The "O" in the serological classification identifies the cell wall lipopolysaccharide antigen, and the "H" identifies the flagella antigen.

Analysis of genomic sequences obtained by BGI Shenzhen shows that the O104:H4 outbreak strain is an enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC or EAggEC) type that has acquired Shiga toxin genes, presumably by horizontal gene transfer.[2][3][4]Genome assembly and copy-number analysis both confirmed that two copies of the Shiga toxin stx2 prophage gene cluster are a distinctive characteristic of the genome of the O104:H4 outbreak strain.[5][6] The O104:H4 strain is characterized by these genetic markers:[6][7]

- Shiga toxin stx2 positive

- tellurite resistance gene cluster positive

- intimin adherence gene negative

- β-lactamases ampC, ampD, ampE, ampG, ampH are present.

The European Commission (EC) integrated approach to food safety[8] defines a case of Shiga-like toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) diarrhea caused by O104:H4 by an acute onset of diarrhea or bloody diarrhea together with the detection of the Shiga toxin 2 (Stx2) or the Shiga gene stx2.[9]Prior to the 2011 outbreak, only one case identified as O104:H4 had been observed, in a woman in South Korea in 2005.[10]

Signs and symptoms

The clinical presentation of E coli O104:H4 is as follows:[11]

- Vomiting

- Bloody diarrhea

- Blood in urine

Pathophysiology

E. coli O104 is a Shiga toxin–producing E. coli (STEC). The toxins cause illness and the associated symptoms by sticking to the intestinal cells and aggravating the cells along the intestinal wall.[12][11] This, in turn, can cause bloody stools to occur. Another effect from this bacterial infection is hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), which is a condition characterized by destruction of red blood cells, that over a long period of time can cause kidney failure.[13]

Infection

A common mode of E. coli O104:H4 infection involves ingestion of fecally contaminated food; the disease can thus be considered a foodborne illness. Most recently in 2011, an outbreak of the O104:H4 strain in Germany caused the deaths of several people, and hundreds were hospitalised.[14][15][11] German authorities traced the infection back to fenugreek sprouts grown from contaminated seeds imported from Egypt, but these results are debated.[citation needed]

Diagnosis

To diagnose infection with STEC, a patient's stool (feces) can be tested in a laboratory for the presence of Shiga toxin. Testing methods used include direct detection of the toxin by immunoassay, or detection of the stx2 gene or other virulence-factor genes by PCR. If infection with STEC is confirmed, the E. coli strain may be serotyped to determine whether O104:H4 is present.[12]

Prevention

Spread of E. coli is prevented simply by thorough hand-washing with soap, washing and hygienically preparing food, and properly heating/cooking food, so the bacteria are destroyed.[16]

Treatment

E. coli O104:H4 is difficult to treat as it is resistant to many antibiotics, although it is susceptible to carbapenems.[14]

References

- ↑ Mellman, Alexander; Harmsen, D; Cummings, CA; et al. (July 20, 2011). "Prospective genomic characterization of the German enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak by rapid next generation sequencing technology". PLoS One. 6 (7): e22751. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0022751. PMC 3140518. PMID 21799941.

- ↑ "BGI Sequences Genome of the Deadly E. coli in Germany and Reveals New Super-Toxic Strain". BGI. 2011-06-02. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ↑ David Tribe (2011-06-02). "BGI Sequencing news: German EHEC strain is a chimera created by horizontal gene transfer". Biology Fortified. Archived from the original on 2012-05-27. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ↑ Maev Kennedy and agencies (2011-06-02). "E. coli outbreak: WHO says bacterium is a new strain". London: guardian.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2011-06-02. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ "BGI releases the complete map of the Germany E. coli O104 genome and attributed the strain as a category of Shiga toxin-producing enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (STpEAEC)". BGI. 2011-06-16. Archived from the original on 2011-06-21. Retrieved 2011-06-20.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Copy number analysis of German outbreak strain E. coli EHEC O104:H4". Johannes Kepler University of Linz. 2011-06-11. Archived from the original on 2011-09-10. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ↑ "Characterization of EHEC O104:H4" (PDF). Robert Koch Institute. 2011-06-03. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-25. Retrieved 2011-06-15.

- ↑ "The EU integrated approach to food safety". Archived from the original on 2011-03-19. Retrieved 2021-08-28.

- ↑ "Case Definition for diarrhoea and haemolytic uremic syndrome caused by O104:H4" (PDF). European Commission. 2011-06-03. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-17. Retrieved 2011-06-16.

- ↑ Bae, WK; Lee, YK; Cho, MS; et al. (June 30, 2006). "A case of haemolytic uremic syndrome caused by Escherichia coli O104:H4". Yonsei Medical Journal. 47 (3): 473–479. doi:10.3349/ymj.2006.47.3.437. PMC 2688167. PMID 16807997.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Reinberg, Steven. "German E. Coli Strain Especially Lethal - Infectious Diseases: Causes, Types, Prevention, Treatment and Facts on MedicineNet.com." Medicinenet.com. MedicineNet Inc, 22 June 2011. Web. 08 Nov. 2011. <http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=146119 Archived 2012-01-18 at the Wayback Machine>.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Frank, C; Werber, D; Cramer, JP; et al. (October 26, 2011). "Epidemic profile of Shiga-toxin–producing Escherichia coli O104:H4 outbreak in Germany". New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (19): 1771–1780. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1106483. PMID 21696328.<http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1106483 Archived 2022-11-12 at the Wayback Machine>

- ↑ European Food Safety Authority. "Shiga Toxin-producing E. Coli (STEC) O104:H4 2011 Outbreaks in Europe:." EFSA Journal. European Food Safety Authority, 3 Nov. 2011. Web. 08 Nov. 2011. <http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/2390 Archived 2022-11-12 at the Wayback Machine>.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Gorman, Christine. "E. Coli on the March: Scientific American." Science News, Articles and Information | Scientific American. Scientific American, 7 Aug. 2011. Web. 08 Nov. 2011. <http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=e-coli-on-the-march Archived 2022-11-12 at the Wayback Machine>.

- ↑ "July 8, 2011: Outbreak of Shiga Toxin-producing E. Coli O104 (STEC O104:H4) Infections Associated with Travel to Germany | E. Coli." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 8 July 2011. Web. 08 Nov. 2011. <https://www.cdc.gov/ecoli/2011/ecolio104/>.

- ↑ "CDC - Escherichia coli O157:H7, General Information - NCZVED." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 8 July 201. Web. 08 Nov. 2011.