Rat-bite fever

| Rat-bite fever | |

|---|---|

| |

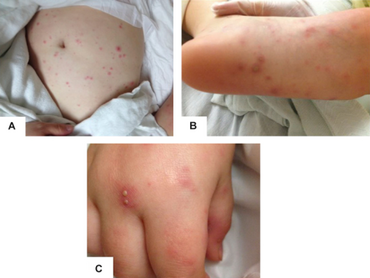

| a)Erythematous papules on abdomen b) purpuric pustules on foot c)pustules on erythematous bases on hand. | |

Rat-bite fever (RBF) is an acute, febrile human illness caused by bacteria transmitted by rodents, in most cases, which is passed from rodent to human by the rodent's urine or mucous secretions. Alternative names for rat-bite fever include streptobacillary fever, streptobacillosis, spirillary fever, bogger, and epidemic arthritic erythema. It is a rare disease spread by infected rodents and caused by two specific types of bacteria:

- Streptobacillus moniliformis, the only reported bacteria that causes RBF in North America (streptobacillary RBF)

- Spirillum minus, common in Asia (spirillary RBF, also known as sodoku). Most cases occur in Japan, but specific strains of the disease are present in the United States, Europe, Australia, and Africa.

Some cases are diagnosed after patients were exposed to the urine or bodily secretions of an infected animal. These secretions can come from the mouth, nose, or eyes of the rodent. The majority of cases are due to the animal's bite. It can also be transmitted through food or water contaminated with rat feces or urine. Other animals can be infected with this disease, including weasels, gerbils, and squirrels. Household pets such as dogs or cats exposed to these animals can also carry the disease and infect humans. If a person is bitten by a rodent, it is important to quickly wash and cleanse the wound area thoroughly with antiseptic solution to reduce the risk of infection.

Symptoms and signs

Symptoms are different for every person depending on the type of rat-bite fever with which the person is infected. Both spirillary and streptobacillary rat-bite fever have a few individual symptoms, although most symptoms are shared. Streptobacillosis is most commonly found in the United States and spirillary rat-bite fever is generally diagnosed in Africa. Rat-bite symptoms are visually seen in most cases and include inflammation around the open sore. A rash can also spread around the area and appear red or purple.[1] Other symptoms associated with streptobacillary rat-bite fever include chills, fever, vomiting, headaches, and muscle aches. Joints can also become painfully swollen and pain can be experienced in the back. Skin irritations such as ulcers or inflammation can develop on the hands and feet. Wounds heal slowly, so symptoms possibly come and go over the course of a few months.

Symptoms associated with spirillary rat-bite fever include issues with the lymph nodes, which often swell or become inflamed as a reaction to the infection. The most common locations of lymph node swelling are in the neck, groin, and underarm.[2] Symptoms generally appear within two to ten days of exposure to the infected animal. It begins with the fever and progresses to the rash on the hands and feet within two to four days. The rash appears all over the body with this form but rarely causes joint pain.

Causes

Two types of Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic bacteria can cause the infection.

Spirillosis

Rat-bite fever transmitted by the Gram-negative coiled rod Spirillum minus (also known as Spirillum minor) is rarer, and is found most often in Asia. In Japan, the disease is called sodoku. Symptoms do not manifest for two to four weeks after exposure to the organism, and the wound through which it entered exhibits slow healing and marked inflammation. The fever lasts longer and is recurring, for months in some cases. Rectal pain and gastrointestinal symptoms are less severe or are absent. Penicillin is the most common treatment.

Streptobacillosis

The streptobacillosis form of rat-bite fever is known by the alternative names Haverhill fever and epidemic arthritic erythema. It is a severe disease caused by Streptobacillus moniliformis, transmitted either by rat bite or ingestion of contaminated products (Haverhill fever). After an incubation period of 2–10 days, Haverhill fever begins with high prostrating fevers, rigors (shivering), headache, and polyarthralgia (joint pain). Soon, an exanthem (widespread rash) appears, either maculopapular (flat red with bumps) or petechial (red or purple spots) and arthritis of large joints can be seen. The organism can be cultivated in blood or articular fluid. The disease can be fatal if untreated in 20% of cases due to malignant endocarditis, meningoencephalitis, or septic shock. Treatment is with penicillin, tetracycline, or doxycycline.

Diagnosis

This condition is diagnosed by detecting the bacteria in skin, blood, joint fluid, or lymph nodes. Blood antibody tests may also be used.[3] To get a proper diagnosis for rat-bite fever, different tests are run depending on the symptoms being experienced.

To diagnosis streptobacillary rat-bite fever, blood or joint fluid is extracted and the organisms living in it are cultured. Diagnosis for spirillary rat bite fever is by direct visualization or culture of spirilla from blood smears or tissue from lesions or lymph nodes.[4]

Prevention

Eliminating exposure is very important when it comes to disease prevention.[5] When handling rodents or cleaning areas where rodents have been, contact between hand and mouth should be avoided.[5] Hands and face should be washed after contact and any scratches both cleaned and antiseptics applied. The effect of chemoprophylaxis following rodent bites or scratches on the disease is unknown. No vaccines are available for these diseases. Improved conditions to minimize rodent contact with humans are the best preventive measures. Animal handlers, laboratory workers, and sanitation and sewer workers must take special precautions against exposure. Wild rodents, dead or alive, should not be touched and pets must not be allowed to ingest rodents. Those living in the inner cities where overcrowding and poor sanitation cause rodent problems are at risk from the disease. Half of all cases reported are children under 12 living in these conditions.

Treatment

Treatment with antibiotics is the same for both types of infection. The condition responds to penicillin, and where allergies to it occur, erythromycin or tetracyclines are used.

Prognosis

When proper treatment is provided for patients with rat-bite fever, the prognosis is positive. Without treatment, the infection usually resolves on its own, although it may take up to a year to do so.[6] A particular strain of rat-bite fever in the United States can progress and cause serious complications that can be potentially fatal. Before antibiotics were used, many cases resulted in death. If left untreated, streptobacillary rat-bite fever can result in infection in the lining of the heart, covering over the spinal cord and brain, or in the lungs. Any tissue or organ throughout the body may develop an abscess.[7]

Epidemiology

Rat-bite fever (RBF) is a zoonotic disease.[8] It can be directly transmitted by rats, gerbils, and mice (the vectors) to humans by either a bite or scratch or it can be passed from rodent to rodent.[9] The causative bacterial agent of RBF has also been observed in squirrels, ferrets, dogs, and pigs.[10] The most common reservoir of the disease is rats because nearly all domestic and wild rats are colonized by the causative bacterial agent, Streptobacillus moniliformis. Most notably, the Black rat (Rattus rattus) and the Norwegian rat (Rattus norvegicus) are recognized as potential reservoirs due to their common use as laboratory animals or kept as pets.[10] The bacteria Streptobacillus moniliformis is found in the rat's upper respiratory tract. Most rats harbor the disease asymptomatically, and signs and symptoms rarely develop.[11] It is estimated that 1 in 10 bites from a rat will result in developing RBF.[12] A person is also at risk of acquiring the bacteria through touching contaminated surfaces with an open wound or mucous membrane[13] or ingestion of contaminated water or food by rodent feces, though this is referred to as Haverhill Fever (epidemic arthritic erythema). RBF is not a contagious disease. That is, it cannot be transferred directly from person to person.[13]

Researchers are challenged in understanding the prevalence of RBF. One factor that limits the known number of cases of RBF in the United States is that it is not a reportable disease there.[14] RBF is classified as a notifiable disease, which means it is required by the state to be reported, however, the state is not mandated to provide that information to the United States Centers for Disease Control. Identification of RBF is also hindered due to the presence of two different etiological bacterial agents, Streptobacillus moniliformis and Spirillum minus.[15] RBF caused by Sp. minus is more commonly found in Asia and is termed Sodoku, whereas St. moniliformis is found more often in the United States and in the Western Hemisphere.[15] Although cases of RBF have been reported all over the world, the majority of cases that have been documented are caused by St. moniliformis primarily in the United States, where approximately 200 cases have been identified and reported.[14][16][17] Due to increasing population density, this illness is being seen more frequently, as humans have increased their contact with animals and the zoonotic diseases they carry.[18] Most cases of the disease have been reported from densely populated regions, such as big cities.[18] The populations at risk have broadened due to the fact that domestic rats have become a common household pet. In the United States it is estimated that children 5 years and younger are the most at risk, receiving 50% of the total exposure, followed by laboratory personnel and then pet store employees.[14][17] Other groups at increased risk are people over 65 years old, immunocompromised individuals, and pregnant women.[19]

Symptoms of RBF include sudden high temperature fevers with rigors, vomiting, headaches, painful joints/arthritis. A red, bumpy rash develops in about 75% of subjects. Symptoms of RBF can develop between 3 days and 3 weeks after exposure.[11] While symptoms differ between Streptobacillary and Spirillary RBF, both types exhibit an incubation period before symptoms manifest.[18][20] Due to its symptoms, RBF is often misdiagnosed by clinicians, leading to lingering symptoms and worsening conditions in patients; left untreated the mortality rate (death rate) of RBF is 13%.[14][21][22] Even when treated, RBF can lead to migratory polyarthralgia, persistent rash, and fatigue [11] which can persist for weeks to years after initial infection and treatment.

See also

References

- ↑ Rat Bite Fever Archived 2016-10-21 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2010-01-26

- ↑ Swollen Lymph Nodes Archived 2010-02-10 at the Wayback Machine Wrong Diagnosis Portal. Retrieved on 2010-01-26

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Rat-bite fever

- ↑ Rat Bite Fever Spirochetes at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Fatal Rat-Bite Fever — Florida and Washington, 2003". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 53 (51/52): 1198–1202. 2005. ISSN 0149-2195. JSTOR 23315671. Archived from the original on 2022-04-06. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- ↑ Rat Bite Fever Overview Archived 2019-09-22 at the Wayback Machine Medical Dictionary Portal. Retrieved on 2010-01-26

- ↑ Rat Bite Fever Description Archived 2019-09-22 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopedia of children's health. Retrieved on 2010-01-26

- ↑ Loridant, Severine; Jaffar-Bandjee, Marie-Christine; Scola, Bernard La (2011-02-04). "Shell Vial Cell Culture as a Tool for Streptobacillus moniliformis "Resuscitation"". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 84 (2): 306–307. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0466. ISSN 0002-9637. PMC 3029187. PMID 21292904.

- ↑ Vanderpool, Matthew R. (September 27, 2007). "Environmental Core Training: Zoonosis, Vector Disease, Poisonous Plants & Basic Control Measures". Tulane University. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Gaastra, Wim; Boot, Ron; Ho, Hoa T.K.; Lipman, Len J.A. (January 2009). "Rat bite fever". Veterinary Microbiology. 133 (2): 211–228. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.09.079. PMID 19008054.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Elliott, Sean P. (January 2007). "Rat Bite Fever and Streptobacillus moniliformis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1128/CMR.00016-06. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 1797630. PMID 17223620.

- ↑ "Notes from the Field: Fatal Rat-Bite Fever in a Child — San Diego County, California, 2013". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-12-04. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Transmission | Rat-bite Fever (RBF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-01-18. Archived from the original on 2020-10-17. Retrieved 2020-11-11.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Elliott, Sean P. (2007). "Rat Bite Fever and Streptobacillus moniliformis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 20 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1128/CMR.00016-06. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 1797630. PMID 17223620.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Group, British Medical Journal Publishing (1948-09-18). "Annotations". Br Med J. 2 (4576): 564–566. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4576.564. ISSN 0007-1447. PMC 2091657. PMID 20787408.

- ↑ Wullenweber, Michael (1995). "Streptobacillus moniliformis-a zoonotic pathogen. Taxonomic considerations, host species, diagnosis, therapy, geographical distribution". Laboratory Animals. 29 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1258/002367795780740375. ISSN 0023-6772. PMID 7707673.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Freels, Liane K.; Elliott, Sean P. (April 2004). "Rat Bite Fever: Three Case Reports and a Literature Review". Clinical Pediatrics. 43 (3): 291–295. doi:10.1177/000992280404300313. ISSN 0009-9228. PMID 15094956. S2CID 46260997.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Graves, Margot H.; Janda, J.Michael (2001). "Rat-bite fever (Streptobacillus moniliformis): A potential emerging disease". International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 5 (3): 151–154. doi:10.1016/s1201-9712(01)90090-6. ISSN 1201-9712. PMID 11724672.

- ↑ "Rat Bite Fever | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-11-15. Archived from the original on 2018-12-04. Retrieved 2018-12-03.

- ↑ "Signs and Symptoms | Rat-bite Fever (RBF) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-11-24. Retrieved 2018-11-13.

- ↑ Dendle, C.; Woolley, I. J.; Korman, T. M. (December 2006). "Rat-bite fever septic arthritis: illustrative case and literature review". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 25 (12): 791–797. doi:10.1007/s10096-006-0224-x. ISSN 0934-9723. PMID 17096137. S2CID 12345288.

- ↑ Meerburg, Bastiaan G; Singleton, Grant R; Kijlstra, Aize (2009-06-23). "Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health". Critical Reviews in Microbiology. 35 (3): 221–270. doi:10.1080/10408410902989837. ISSN 1040-841X. PMID 19548807. S2CID 205694138.

https://www.cdc.gov/rat-bite-fever/index.html Archived 2022-01-19 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- "Rat-bite Fever (RBF)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (January 2005). "Fatal rat-bite fever—Florida and Washington, 2003". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 53 (51): 1198–202. PMID 15635289. Archived from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2022-03-17.

- Rat-bite fever (MyOptumHealth.com) Archived 2022-04-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Tandon, R; Lee, M; Curran, E; Demierre, MF; Sulis, CA (Dec 15, 2006). "A 26-year-old woman with a rash on her extremities". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 43 (12): 1585–6, 1616–7. doi:10.1086/509574. PMID 17109293.

- Centers for Disease Control, (CDC) (Jun 8, 1984). "Rat-bite fever in a college student--California". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 33 (22): 318–20. PMID 6427575. Archived from the original on March 19, 2021. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |