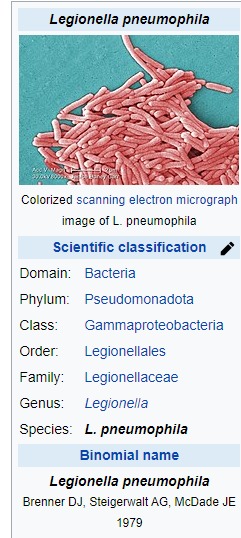

Legionella pneumophila

Legionella pneumophila is a thin, aerobic, pleomorphic, flagellated, non-spore-forming, Gram-negative bacterium of the genus Legionella.[1][2] L. pneumophila is the primary human pathogenic bacterium in this group and is the causative agent of Legionnaires' disease, also known as legionellosis.[3]

In nature, L. pneumophila infects freshwater and soil amoebae of the genera Acanthamoeba. The mechanism of infection is similar in amoeba and human cells.[4][5]

Characterization

L. pneumophila is a Gram-negative, non-encapsulated, aerobic bacillus with a single, polar flagellum often characterized as being a coccobacillus. It is aerobic and unable to hydrolyse gelatin or produce urease. It is also non-fermentative. L. pneumophila is neither pigmented nor does it autofluoresce. It is oxidase- and catalase-positive, and produces beta-lactamase. L. pneumophila colony morphology is gray-white with a textured, cut-glass appearance; it also requires cysteine and iron to thrive.[6][7][8]

Cell membrane structure

While L. pneumophila is categorized as a Gram-negative organism, it stains poorly due to its unique lipopolysaccharide content in the outer leaflet of the outer cell membrane.[9]

The basis for the somatic antigen specificity of organism are located on side chains of its cell wall. The chemical composition of these side chains both with respect to components and arrangement of the different sugars, determines the nature of the somatic or O-antigenic determinants, which are important means of serologically classifying many Gram-negative bacteria. [10][7][9]

Detection

Sera have been used both for slide agglutination studies and for direct detection of bacteria in tissues using immunofluorescence via fluorescent-labelled antibody. Specific antibody in patients can be determined by the indirect fluorescent antibody test. ELISA and microagglutination tests have also been successfully applied.Legionella stains poorly with Gram stain, stains positive with silver, and is cultured on charcoal yeast extract with iron and cysteine.[11][12]

Genomics

The determination and publication of the complete genome sequences of three clinical L. pneumophila isolates in 2004 paved the way for the understanding of the molecular biology of L. pneumophila in particular and Legionella in general. In-depth comparative genome analysis using DNA arrays to study the gene content of 180 Legionella strains revealed high genome plasticity and frequent horizontal gene transfer. Further insight in the L. pneumophila lifecycle was gained by investigating the gene expression profile of L. pneumophila in Acanthamoeba castellanii, its natural host. L. pneumophila exhibits a biphasic lifecycle and defines transmissive and replicative traits according to gene expression profiles.[2][13]

Genetic transformation

Transformation is a bacterial adaptation involving the transfer of DNA from one bacterium to another through the surrounding liquid medium. Transformation is a bacterial form of sexual reproduction. In order for a bacterium to bind, take up, and recombine exogenous DNA into its chromosome, it must enter a special physiological state referred to as "competence".[14][15][16]

To determine which molecules may induce competence in L. pneumophila, 64 toxic molecules were tested.[17] Only six of these molecules, all DNA-damaging agents, caused strong induction of competence. These were mitomycin C (which introduces DNA inter-strand crosslinks), norfloxacin, ofloxacin, and nalidixic acid (inhibitors of DNA gyrase that cause double-strand breaks), bicyclomycin (causes double-strand breaks), and hydroxyurea (causes oxidation of DNA bases). These results suggest that competence for transformation in L. pneumophilia evolved as a response to DNA damage.[17] Perhaps induction of competence provides a survival advantage in a natural host, as occurs with other pathogenic bacteria.[14]

Mechanism

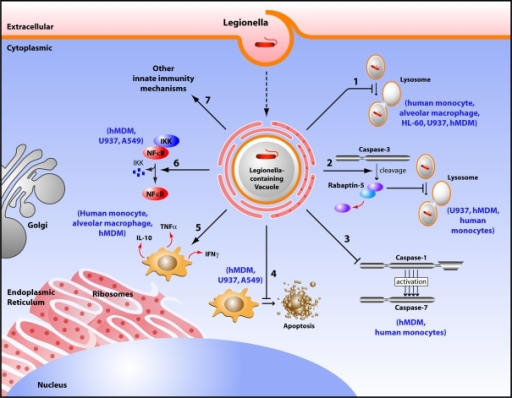

In humans, L. pneumophila invades and replicates inside macrophages. The internalization of the bacteria can be enhanced by the presence of antibody and complement, but is not absolutely required. Internalization of the bacteria appears to occur through phagocytosis. However, L. pneumophila is also capable of infecting non-phagocytic cells through an unknown mechanism. A rare form of phagocytosis known as coiling phagocytosis has been described for L. pneumophila, but this is not dependent on the Dot/Icm (intracellular multiplication/defect in organelle trafficking genes) bacterial secretion system and has been observed for other pathogens.[19]

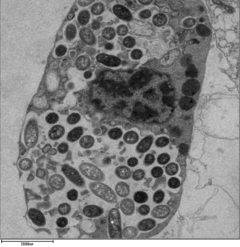

Once internalized, the bacteria surround themselves in a membrane-bound vacuole that does not fuse with lysosomes that would otherwise degrade the bacteria. In this protected compartment, the bacteria multiply.[18][19]

Dot/Icm type IV secretion system and effector proteins

The bacteria use a type IVB secretion system known as Dot/Icm to inject effector proteins into the host. These effectors are involved in increasing the bacteria's ability to survive inside the host cell. L. pneumophila encodes for over 330 "effector" proteins,[20] which are secreted by the Dot/Icm translocation system to interfere with host cell processes to aid bacterial survival.

It has been predicted that the genus Legionella encodes more than 10,000 and possibly up to ~18,000 effectors that have a high probability to be secreted into their host cells.[21][13]

One key way in which L. pneumophila uses its effector proteins is to interfere with fusion of the Legionella-containing vacuole with the host's endosomes, and thus protect against lysis.[22]

Knock-out studies of Dot/Icm translocated effectors indicate that they are vital for the intracellular survival of the bacterium, but many individual effector proteins are thought to function redundantly, in that single-effector knock-outs rarely impede intracellular survival. This high number of translocated effector proteins and their redundancy is likely a result of the bacterium having evolved in many different protozoan hosts.[23]

Legionella-containing vacuole

For Legionella to survive within macrophages and protozoa, it must create a specialized compartment known as the Legionella-containing vacuole (LCV). Through the action of the Dot/Icm secretion system, the bacteria are able to prevent degradation by the normal endosomal trafficking pathway and instead replicate. Shortly after internalization, the bacteria specifically recruit endoplasmic reticulum-derived vesicles and mitochondria to the LCV while preventing the recruitment of endosomal markers such as Rab5a and Rab7a. Formation and maintenance of the vacuoles are crucial for pathogenesis; bacteria lacking the Dot/Icm secretion system are not pathogenic and cannot replicate within cells, while deletion of the Dot/Icm effector SdhA results in destabilization of the vacuolar membrane and no bacterial replication.[24][25]

Nutrient acquisition

Legionella is auxotrophic for seven amino acids: cysteine, leucine, methionine, valine, threonine, isoleucine, and arginine. Once inside the host cell, Legionella needs nutrients to grow and reproduce. Inside the vacuole, nutrient availability is low; the high demand of amino acids is not covered by the transport of free amino acids found in the host cytoplasm. To improve the availability of amino acids, the parasite promotes the host mechanisms of proteasomal degradation. This generates an excess of free amino acids in the cytoplasm of L. pneumophila-infected cells that can be used for intravacuolar proliferation of the parasite.To obtain amino acids, L. pneumophila uses the AnkB F-Box effector, which is farnesylated by the activity of three host enzymes localized in the membrane of the LCV: farnesyltransferase, Ras-converting enzyme-1 protease, and ICMT. Farnesylation allows AnkB to get anchored into the cytoplasmic side of the vacuole.Once AnkB is anchored into the LCV membrane, it interacts with the SCF1 ubiquitin ligase complex and functions as a platform for the docking of K48-linked polyubiquitinated proteins to the LCV ( K48-linked polyubiquitination is a marker for proteasomal degradation that releases peptides, which are quickly degraded to amino acids by various oligopeptidases and aminopeptidases present in the cytoplasm; amino acids are imported into the LCV through various amino acid transporters such as the neutral amino acid transporter B(0)[26][27]). The amino acids are the primary carbon and energy source of L. pneumophila, that have almost 12 classes of ABC-transporters, amino acid permeases, and many proteases, to exploit it. The imported amino acids are used by L. pneumophila to generate energy through the TCA cycle (Krebs cycle) and as sources of carbon and nitrogen.However, promotion of proteasomal degradation for the obtention of amino acids may not be the only virulence strategy to obtain carbon and energy sources from the host.[28][29][30][31]

Reservoirs

L. pneumophila is a facultative intracellular parasite that can invade and replicate inside amoebae in the environment, especially species of the genera Acanthamoeba and Naegleria, which can thus serve as a reservoir for L. pneumophila. These hosts also provide protection from environmental stresses, such as chlorination.[32]

Legionella has been shown to proliferate on the walls of pipes in biofilms.[33]

Sloughed legionella from biofilms in plumbing systems can be aerosolized through faucets, showers, sprinklers, and other fixtures which can lead to infection after prolonged exposure.[33]

Infection

Signs and symptoms

Those with Legionnaires' disease usually have fever, chills, and a cough, which may be dry or may produce sputum. Almost all experience fever, while around half have cough with sputum, and one-third cough up blood or bloody sputum. Some also have muscle aches, headache, tiredness, loss of appetite, loss of coordination, chest pain, or diarrhea and vomiting. A significant percentage of those with Legionnaires' disease have gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as neurological symptoms, including confusion and impaired cognition.[34][35]

Diagnosis

The most useful diagnostic tests detect the bacteria in coughed-up mucus, find Legionella antigens in urine samples, or allow comparison of Legionella antibody levels in two blood samples taken 3–6 weeks apart. A urine antigen test is simple, quick, and very reliable, but only detects L. pneumophila serogroup 1, which accounts for 70% of disease caused by L. pneumophila, which means use of the urine antigen test alone may miss as many as 30% of cases.[36][37][38] This test was developed by Richard Kohler in 1982.[39]

Treatment

Macrolides (azithromycin or clarithromycin) or fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin or moxifloxacin) are the standard treatment for Legionella pneumonia in humans, with levofloxacin being considered first line with increasing resistance to azithromycin. Two studies support superiority of levofloxacin over macrolides, although not FDA approved.[40]

Epidemiology

In the United States, approximately 3 infections with L. pneumophila appear per 100,000 people per year.[41] The infections peak in the summer. Within endemic regions, about 4% to 5% of pneumonia cases are caused by L. pneumophila.[42]

Research

Several enzymes in the bacteria have been proposed as tentative drug targets. For example, enzymes in the iron uptake pathway have been suggested as important drug targets. Further, a cN-II class of IMP/GMP specific 5´-nucleotidase which has been extensively characterized kinetically. The tetrameric enzyme shows aspects of positive homotropic cooperativity, substrate activation and presents a unique allosteric site that can be targeted to design effective drugs against the enzyme and thus, the organism. Moreover, the enzyme is distinct than its human counterpart making it an attractive target for drug development.[43][44][45]

References

- ↑ Madigan M, Martinko J, eds. (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-144329-1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Heuner K, Swanson M, eds. (2008). Legionella: Molecular Microbiology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-26-4. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ↑ Gomez-Valero, Laura; Buchrieser, Carmen (May 2019). "Intracellular parasitism, the driving force of evolution of Legionella pneumophila and the genus Legionella". Genes and Immunity. 20 (5): 394–402. doi:10.1038/s41435-019-0074-z. ISSN 1476-5470. Archived from the original on 2023-10-23. Retrieved 2024-03-09.

- ↑ Rowbotham TJ (December 1980). "Preliminary report on the pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila for freshwater and soil amoebae". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 33 (12): 1179–83. doi:10.1136/jcp.33.12.1179. PMC 1146371. PMID 7451664.

- ↑ Li, Pengfei; Vassiliadis, Dane; Ong, Sze Ying; Bennett-Wood, Vicki; Sugimoto, Chihiro; Yamagishi, Junya; Hartland, Elizabeth L.; Pasricha, Shivani (2020). "Legionella pneumophila Infection Rewires the Acanthamoeba castellanii Transcriptome, Highlighting a Class of Sirtuin Genes". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 10. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.00428/full. ISSN 2235-2988. Archived from the original on 2024-02-25. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ↑ Iliadi, Valeria; Staykova, Jeni; Iliadis, Sergios; Konstantinidou, Ina; Sivykh, Polina; Romanidou, Gioulia; Vardikov, Daniil F.; Cassimos, Dimitrios; Konstantinidis, Theocharis G. (18 October 2022). "Legionella pneumophila: The Journey from the Environment to the Blood". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 11 (20): 6126. doi:10.3390/jcm11206126. ISSN 2077-0383. Archived from the original on 11 March 2024. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Winn, Washington C. (1996). "Legionella". Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Archived from the original on 2023-12-24. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ↑ Wanger, Audrey (2017). Microbiology and molecular diagnosis in pathology: a comprehensive review for board preparation, certification and clinical practice. Amsterdam, Netherlands ; Cambridge, MA: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-805351-5. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ryan KJ; Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Xu, Li; Luo, Zhao-Qing (2013). "Cell biology of infection by Legionella pneumophila". Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur. 15 (2): 157–167. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2012.11.001. ISSN 1286-4579. Archived from the original on 2024-03-14. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ↑ Pierre, David M.; Baron, Julianne; Yu, Victor L.; Stout, Janet E. (29 August 2017). "Diagnostic testing for Legionnaires' disease". Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 16 (1): 59. doi:10.1186/s12941-017-0229-6. ISSN 1476-0711. Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ↑ Bai, Lu; Yang, Wei; Li, Yuanyuan (12 January 2023). "Clinical and Laboratory Diagnosis of Legionella Pneumonia". Diagnostics. 13 (2): 280. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13020280. ISSN 2075-4418. Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Gomez-Valero, Laura; Rusniok, Christophe; Carson, Danielle; Mondino, Sonia; Pérez-Cobas, Ana Elena; Rolando, Monica; Pasricha, Shivani; Reuter, Sandra; Demirtas, Jasmin; Crumbach, Johannes; Descorps-Declere, Stephane; Hartland, Elizabeth L.; Jarraud, Sophie; Dougan, Gordon; Schroeder, Gunnar N.; Frankel, Gad; Buchrieser, Carmen (5 February 2019). "More than 18,000 effectors in the Legionella genus genome provide multiple, independent combinations for replication in human cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 116 (6): 2265–2273. doi:10.1073/pnas.1808016116. ISSN 1091-6490. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Michod RE, Bernstein H, Nedelcu AM (May 2008). "Adaptive value of sex in microbial pathogens" (PDF). Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 267–85. doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2008.01.002. PMID 18295550. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-05-11. Retrieved 2023-04-17.

- ↑ Buchrieser, Carmen; Charpentier, Xavier (2013). "Induction of competence for natural transformation in Legionella pneumophila and exploitation for mutant construction". Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.). 954: 183–195. doi:10.1007/978-1-62703-161-5_9. ISSN 1940-6029. Archived from the original on 2023-11-17. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ↑ Chen, Inês; Christie, Peter J.; Dubnau, David (2 December 2005). "The Ins and Outs of DNA Transfer in Bacteria". Science (New York, N.Y.). 310 (5753): 1456–1460. doi:10.1126/science.1114021. ISSN 0036-8075. Archived from the original on 19 November 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Charpentier X, Kay E, Schneider D, Shuman HA (March 2011). "Antibiotics and UV radiation induce competence for natural transformation in Legionella pneumophila". Journal of Bacteriology. 193 (5): 1114–21. doi:10.1128/JB.01146-10. PMC 3067580. PMID 21169481.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Khweek, Arwa Abu; Amer, Amal (2010). "Replication of Legionella Pneumophila in Human Cells: Why are We Susceptible?". Frontiers in Microbiology. 1: 133. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2010.00133. ISSN 1664-302X. Archived from the original on 2022-06-17. Retrieved 2024-03-11.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Rittig MG, Krause A, Häupl T, Schaible UE, Modolell M, Kramer MD, Lütjen-Drecoll E, Simon MM, Burmester GR (October 1992). "Coiling phagocytosis is the preferential phagocytic mechanism for Borrelia burgdorferi". Infection and Immunity. 60 (10): 4205–12. doi:10.1128/iai.60.10.4205-4212.1992. PMC 257454. PMID 1398932.

- ↑ Ensminger AW (February 2016). "Legionella pneumophila, armed to the hilt: justifying the largest arsenal of effectors in the bacterial world". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 29: 74–80. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2015.11.002. PMID 26709975.

- ↑ Burstein D, Amaro F, Zusman T, Lifshitz Z, Cohen O, Gilbert JA, Pupko T, Shuman HA, Segal G (February 2016). "Genomic analysis of 38 Legionella species identifies large and diverse effector repertoires". Nature Genetics. 48 (2): 167–75. doi:10.1038/ng.3481. PMC 5050043. PMID 26752266.

- ↑ Pan X, Lührmann A, Satoh A, Laskowski-Arce MA, Roy CR (June 2008). "Ankyrin repeat proteins comprise a diverse family of bacterial type IV effectors". Science. 320 (5883): 1651–4. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1651P. doi:10.1126/science.1158160. PMC 2514061. PMID 18566289.

- ↑ Jules M, Buchrieser C (June 2007). "Legionella pneumophila adaptation to intracellular life and the host response: clues from genomics and transcriptomics". FEBS Letters. 581 (15): 2829–38. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.026. PMID 17531986. S2CID 23203471.

- ↑ Harding CR, Stoneham CA, Schuelein R, Newton H, Oates CV, Hartland EL, Schroeder GN, Frankel G (July 2013). "The Dot/Icm effector SdhA is necessary for virulence of Legionella pneumophila in Galleria mellonella and A/J mice". Infection and Immunity. 81 (7): 2598–605. doi:10.1128/IAI.00296-13. PMC 3697626. PMID 23649096.

- ↑ Creasey EA, Isberg RR (February 2012). "The protein SdhA maintains the integrity of the Legionella-containing vacuole". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (9): 3481–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121286109. PMC 3295292. PMID 22308473.

- ↑ Price, Christopher T. D.; Abu Kwaik, Yousef (15 January 2021). "Evolution and Adaptation of Legionella pneumophila to Manipulate the Ubiquitination Machinery of Its Amoebae and Mammalian Hosts". Biomolecules. 11 (1): 112. doi:10.3390/biom11010112. ISSN 2218-273X. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ↑ Grice, Guinevere L.; Nathan, James A. (1 September 2016). "The recognition of ubiquitinated proteins by the proteasome". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 73 (18): 3497–3506. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2255-5. ISSN 1420-9071. Archived from the original on 14 February 2024. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ↑ Best, Ashley; Abu Kwaik, Yousef (2019). "Nutrition and bi-partite metabolism of intracellular pathogens". Trends in microbiology. 27 (6): 550–561. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2018.12.012. ISSN 0966-842X. Archived from the original on 2024-03-17. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ↑ Manske, Christian; Hilbi, Hubert (2014). "Metabolism of the vacuolar pathogen Legionella and implications for virulence". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 4. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2014.00125/full. ISSN 2235-2988. Archived from the original on 2024-01-24. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ↑ Best, Ashley; Kwaik, Yousef Abu (October 9, 2018). "Evolution of the Arsenal of Legionella pneumophila Effectors to Modulate Protist Hosts". mBio. 9 (5): 1313. doi:10.1128/mBio.01313-18. PMC 6178616. PMID 30301851.

- ↑ Shames, Stephanie R. (18 April 2023). "Eat or Be Eaten: Strategies Used by Legionella to Acquire Host-Derived Nutrients and Evade Lysosomal Degradation". Infection and Immunity. 91 (4). doi:10.1128/iai.00441-22. Archived from the original on 22 March 2024. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ↑ Greub G, Raoult D (November 2003). "Morphology of Legionella pneumophila according to their location within Hartmanella vermiformis". Research in Microbiology. 154 (9): 619–21. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2003.08.003. PMID 14596898.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Abdel-Nour, Mena; Duncan, Carla; Low, Donald E.; Guyard, Cyril (31 October 2013). "Biofilms: The Stronghold of Legionella pneumophila". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 14 (11): 21660–21675. doi:10.3390/ijms141121660. ISSN 1422-0067. Archived from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ↑ Edelstein PH (March 2008). "Legionnaires' Disease: History and Clinical Findings". In Heuner K, Swanson M (eds.). Legionella: Molecular Microbiology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-26-4.

- ↑ Brady, Mark F.; Awosika, Ayoola O.; Sundareshan, Vidya (2024). "Legionnaires' Disease". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2022-06-23. Retrieved 2024-03-11.

- ↑ "Legionnaires Disease Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2 August 2022. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ↑ Fields, B. S.; Benson, R. F.; Besser, R. E. (2002). "Legionella and Legionnaires' Disease: 25 Years of Investigation". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 15 (3): 506–526. doi:10.1128/CMR.15.3.506-526.2002. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 118082. PMID 12097254.

- ↑ Gattuso, G; Rizzo, R; Lavoro, A; Spoto, V; Porciello, G; Montagnese, C; Cinà, D; Cosentino, A; Lombardo, C; Mezzatesta, ML; Salmeri, M (9 March 2022). "Overview of the Clinical and Molecular Features of Legionella Pneumophila: Focus on Novel Surveillance and Diagnostic Strategies". Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland). 11 (3). doi:10.3390/antibiotics11030370. PMID 35326833. Archived from the original on 14 March 2024. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ↑ Kohler R, Wheat LJ (September 1982). "Rapid diagnosis of pneumonia due to Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1". J. Infect. Dis. 146 (3): 444. doi:10.1093/infdis/146.3.444. PMID 7050258.

- ↑ The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy 2013

- ↑ "Legionnaires Disease, Pontiac Fever Fast Facts - Legionella - CDC". www.cdc.gov. 30 April 2018. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ↑ "RKI RKI-Ratgeber für Ärzte". 19 July 2011. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011.

- ↑ Cianciotto, Nicholas P (May 2015). "An update on iron acquisition by Legionella pneumophila : new pathways for siderophore uptake and ferric iron reduction". Future Microbiology. 10 (5): 841–851. doi:10.2217/fmb.15.21. ISSN 1746-0913. PMC 4461365. PMID 26000653.

- ↑ Vucelić, B; Hadzić, N; Knezević, S (1 February 1985). "[Inflammatory bowel diseases--personal experience]". Lijecnicki vjesnik. 107 (2): 64–67. ISSN 1849-2177. Archived from the original on 22 March 2024. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ↑ Srinivasan, Bharath; Forouhar, Farhad; Shukla, Arpit; Sampangi, Chethana; Kulkarni, Sonia; Abashidze, Mariam; Seetharaman, Jayaraman; Lew, Scott; Mao, Lei; Acton, Thomas B.; Xiao, Rong; Everett, John K.; Montelione, Gaetano T.; Tong, Liang; Balaram, Hemalatha (March 2014). "Allosteric regulation and substrate activation in cytosolic nucleotidase II from L egionella pneumophila". The FEBS Journal. 281 (6): 1613–1628. doi:10.1111/febs.12727. ISSN 1742-464X. Archived from the original on 2024-03-22. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

External links

- Major topic "Legionella pneumophila": free-full text articles in PubMed Archived 2023-07-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Legionella pneumophila, causative agent of Legionnaire's disease and Pontiac fever at MetaPathogen

- Type strain of Legionella pneumophila at BacDive - the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Archived 2016-06-17 at the Wayback Machine