Trench fever

| Trench fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Wolhynia fever, shin bone fever, Meuse fever, His disease and His–Werner disease | |

| Symptoms | fever |

| Duration | 5 days |

| Causes | infected insect bite |

| Prevention | body hygiene |

| Medication | Tetracycline-group antibiotics |

| Deaths | Rare |

Trench fever (also known as "five-day fever", "quintan fever" (Latin: febris quintana), and "urban trench fever"[1]) is a moderately serious disease transmitted by body lice. It infected armies in Flanders, France, Poland, Galicia, Italy, Salonika, Macedonia, Mesopotamia, Russia and Egypt in World War I.[2][3] Three noted sufferers during WWI were the authors J. R. R. Tolkien,[4] A. A. Milne,[5] and C. S. Lewis.[6] From 1915 to 1918 between one-fifth and one-third of all British troops reported ill had trench fever while about one-fifth of ill German and Austrian troops had the disease.[2] The disease persists among the homeless.[7] Outbreaks have been documented, for example, in Seattle[8] and Baltimore in the United States among injection drug users[9] and in Marseille, France,[8] and Burundi.[10]

Trench fever is also called Wolhynia fever, shin bone fever, Meuse fever, His disease and His–Werner disease or Werner-His disease (after Wilhelm His Jr. and Heinrich Werner).

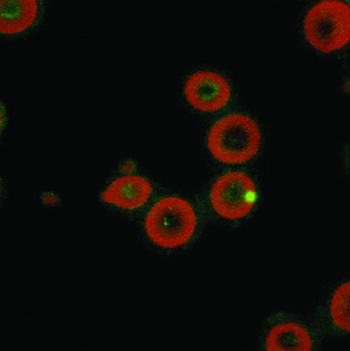

The disease is caused by the bacterium Bartonella quintana (older names: Rochalimea quintana, Rickettsia quintana), found in the stomach walls of the body louse.[3] Bartonella quintana is closely related to Bartonella henselae, the agent of cat scratch fever and bacillary angiomatosis.

Signs and symptoms

The disease is classically a five-day fever of the relapsing type, rarely exhibiting a continuous course. The incubation period is relatively long, at about two weeks. The onset of symptoms is usually sudden, with high fever, severe headache, pain on moving the eyeballs, soreness of the muscles of the legs and back, and frequently hyperaesthesia of the shins. The initial fever is usually followed in a few days by a single, short rise but there may be many relapses between periods without fever.[11] The most constant symptom is pain in the legs.[3] Recovery takes a month or more. Lethal cases are rare, but in a few cases "the persistent fever might lead to heart failure".[4][11] Aftereffects may include neurasthenia, cardiac disturbances and myalgia.[11]

Pathophysiology

Bartonella quintana is transmitted by contamination of a skin abrasion or louse-bite wound with the faeces of an infected body louse (Pediculus humanus corporis). There have also been reports of an infected louse bite passing on the infection.[3][11]

Diagnosis

Serological testing is typically used to obtain a definitive diagnosis. Most serological tests would succeed only after a certain period of time past the symptom onset (usually a week). The differential diagnosis list includes typhus, ehrlichiosis, leptospirosis, Lyme disease, and virus-caused exanthema (measles or rubella).[citation needed]

Treatment

[12] The treatment of trench fever can vary from case to case, as the human body has the capability to rid the disease naturally. Some patients will require treatment, and others will not. For those who do require treatment, the best treatment comes by way of doxycycline in combination with gentamicin. Chloramphenicol is an alternative medication recommended under circumstances that render use of tetracycline derivates undesirable, such as severe liver disease, kidney dysfunction, in children under nine years and in pregnant women. The medication is administered for seven to ten days.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

Trench fever is a vector borne disease in which humans are primarily the main hosts. The vector through which the disease is typically transmitted is referred to as the human body louse “Pediculus humanus humanus”, which is better known as lice. The British Expeditionary Force Pyrexia of Unknown Origin Enquiry Sub-Committee concluded that the specific means by which the vector infected the host was louse waste entering the body through abraded skin.[13] Although the disease is typically found in humans, the gram negative bacterium which induce the disease have been seen in mammals such as dogs, cats, and macaques in small numbers.[14]

Being that the vector of the disease is human body louse, it can be determined that the main risk factors for infection are mostly in relation to contracting body louse. Specifically, some risk factors include: body louse infestation, overcrowded and unhygienic conditions, body hygiene, war, famine, malnutrition, alcoholism, homelessness, and intravenous drug abuse.[15]

The identified risk factors directly correlate with the subpopulations of identified infected persons throughout the duration of the known disease. Historically, trench fever was found in young male soldiers of World War I, whereas in the 21st century the disease mostly has a prevalence in middle aged homeless men. This can be seen when looking at a 21st-century outbreak of the disease in Denver, Colorado, where researcher David McCormick and his colleagues came across the gram negative bacterium in 15% of the 241 homeless persons who were tested.[16] Another study done in Marseille, France found the bacterium in 5.4% of the 930 homeless individuals they tested.[17]

History

Trench fever was first described and reported by British major John Graham in June 1915. He reported symptoms such as dizziness, headaches, and pain in the shins and back. The disease was most common in the military and consequently took much longer to identify than usual. These cases were originally confused for dengue, sandfly, or paratyphoid fever. Because insects were the suspected vector of transmission, Alexander Peacock published a study of the body louse in 1916. Due in part to his findings, the louse was determined to be the primary cause of transmission by many, but this was still contested by multiple voices in the field such as John Muir who believed the disease was of the viral nature. In 1917, the Trench Fever Investigation Commission (TFIC) had its first meeting. The TFIC performed experiments with infected blood and louse, and learned much about the disease and louse behavior. Also in 1917 the American Red Cross started the Medical Research Committee (MRC). The MRC performed human experiments on trench fever, and their research was published in March 1918.[18] The MRC and TFIC findings were very similar essentially confirming the louse as the vector of transmission. It was not until the 1920s that the bacteria B Quintana was identified as the cause of trench fever.

References

- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 1095. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Justina Hamilton Hill (1942). Silent Enemies: The Story of the Diseases of War and Their Control. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Francis Timoney; William Arthur Hagan (1973). Hagan and Bruner's Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of Domestic Animals. Cornell University Press.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 John Garth (2003). Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth. HarperCollins Publishers.

- ↑ Humphrey Carpenter; Mari Prichard (1984). The Oxford companion to children's literature. Oxford University Press. p. 351. ISBN 9780192115829.

- ↑ C. S. Lewis (1955). Surprised By Joy. Harcourt.

- ↑ Sarah Perloff (17 January 2020). "Trench Fever". EMedicine. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 Ohl, M. E.; Spach, D. H. (1 July 2000). "Bartonella quintana and Urban Trench Fever". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 31 (1): 131–135. doi:10.1086/313890. PMID 10913410.

- ↑ Comer, James A. (25 November 1996). "Antibodies to Bartonella Species in Inner-city Intravenous Drug Users in Baltimore, Md". Archives of Internal Medicine. 156 (21): 2491–5. doi:10.1001/archinte.1996.00440200111014. PMID 8944742.

- ↑ Raoult, D; Ndihokubwayo, JB; Tissot-Dupont, H; Roux, V; Faugere, B; Abegbinni, R; Birtles, RJ (1998). "Outbreak of epidemic typhus associated with trench fever in Burundi". The Lancet. 352 (9125): 353–358. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12433-3. PMID 9717922. S2CID 25814472.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Edward Rhodes Stitt (1922). The Diagnostics and treatment of tropical diseases. P. Blakiston's Son & Co.

- ↑ Rolain, J. M.; Brouqui, P.; Koehler, J. E.; Maguina, C.; Dolan, M. J.; Raoult, D. (June 2004). "Recommendations for Treatment of Human Infections Caused by Bartonella Species". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 48 (6): 1921–1933. doi:10.1128/AAC.48.6.1921-1933.2004. ISSN 0066-4804. PMC 415619. PMID 15155180.

- ↑ "Trench Fever in the First World War". www.kumc.edu. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ↑ "Facts about Bartonella quintana infection ('trench fever')". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ↑ "Trench Fever: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology". 21 October 2021. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "People experiencing homelessness face 'substantial risk' for trench fever". www.healio.com. 22 May 2021. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ↑ Badiaga, S.; Brouqui, P. (1 April 2012). "Human louse-transmitted infectious diseases". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 18 (4): 332–337. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03778.x. ISSN 1198-743X. PMID 22360386. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ↑ Anstead, Gregory M (1 August 2016). "The centenary of the discovery of trench fever, an emerging infectious disease of World War 1". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16 (8): e164–e172. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30003-2. ISSN 1473-3099. PMC 7106389. PMID 27375211.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- Articles containing Latin-language text

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2021

- Use dmy dates from August 2019

- Bacterial diseases

- Bacterium-related cutaneous conditions

- Trench warfare