Vibrio parahaemolyticus

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | |

|---|---|

| |

| SEM image of V. parahaemolyticus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Vibrionales |

| Family: | Vibrionaceae |

| Genus: | Vibrio |

| Species: | V. parahaemolyticus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Fujino et al. 1951)

Sakazaki et al. 1963 | |

Vibrio parahaemolyticus (V. parahaemolyticus) is a curved, rod-shaped, Gram-negative bacterium found in the sea and in estuaries which, when ingested, may cause gastrointestinal illness in humans.[1] V. parahaemolyticus is oxidase positive, facultatively aerobic, and does not form spores. Like other members of the genus Vibrio, this species is motile, with a single, polar flagellum.[2]

Pathogenesis

While infection can occur by the fecal-oral route, ingestion of bacteria in raw or undercooked seafood, usually oysters, is the predominant cause of the acute gastroenteritis caused by V. parahaemolyticus.[3] Wound infections also occur, but are less common than seafood-borne disease. The disease mechanism of V. parahaemolyticus infections has not been fully elucidated.[4]

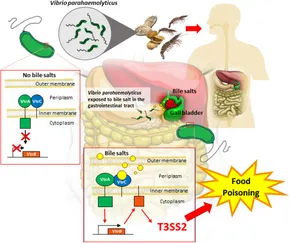

Clinical isolates usually possess a pathogenicity island (PAI) on the second chromosome. The PAI can be acquired by horizontal gene transfer and contains genes for several virulence factors. Two fully sequenced variants exist of the V. parahaemolyticus PAI with distinctly different lineages.[5][6] Each PAI variant contains a genetically distinct Type III Secretion System (T3SS), which is capable of injecting virulence proteins into host cells to disrupt host cell functions or cause cell death by apoptosis. The two known T3SS variants on V. parahaemolyticus chromosome 2 are known as T3SS2α and T3SS2β. These variants correspond to the two known PAI variants. Aside from the T3SS, two genes encoding well-characterized virulence proteins are typically found on the PAI, the thermostable direct hemolysin gene (tdh) and/or the tdh-related hemolysin gene (trh). Strains possessing one or both of these hemolysins exhibit beta-hemolysis on blood agar plates. A distinct correlation seems to exist between presence of tdh, trh, and the two known T3SS variants: observations have shown T3SS2α correlating with tdh+/trh- strains, while T3SS2β correlates with tdh-/trh+ strains.[7]

Infection

The incubation period of about 24 hours is followed by intense watery or bloody diarrhea accompanied by nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and sometimes a fever. Symptoms typically resolve within 72 hours, but can persist for up to 10 days in immunocompromised individuals. As the vast majority of cases of V. parahaemolyticus food poisoning are self-limiting, doxycycline is not typically necessary. In severe cases, ORS is indicated.[2]

Epidemiology

Outbreaks tend to be concentrated along coastal regions during the summer and early fall when higher water temperatures favor higher levels of bacteria. Seafood most often implicated includes squid, mackerel, tuna, sardines, crab, conch, shrimp, and bivalves, such as oysters and clams. In the Northeast United States, there is an increasing incidence of illness due to oysters contaminated with V. parahaemolyticus, which is associated with warmer waters from the Gulf of Mexico moving northward.[9]

Additionally, swimming or working in affected areas can lead to infections of the eyes, ears,[10] or open cuts and wounds. Following Hurricane Katrina, 22 wounds were infected with Vibrio, three of which were caused by V. parahaemolyticus, and two of these led to death.

Hosts

Hosts of V. parahaemolyticus include:

- Clithon retropictus[11]

- Litopenaeus shrimp (suspected; possibly causes necrotising hepatopancreatitis)[12]

- Nerita albicilla[11]

- Magallana gigas[13][14]

References

- ↑ What is Vibrio parahaemolyticus?, archived from the original on 25 September 2018, retrieved 25 September 2018

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Finkelstein RA (1996). Baron S; et al. (eds.). Cholera, Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139, and Other Pathogenic Vibrios. In: Barron's Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. (via NCBI Bookshelf).

- ↑ Baffone W, Casaroli A, Campana R, et al. (2005). "'In vivo' studies on the pathophysiological mechanism of Vibrio parahaemolyticus TDH(+)-induced secretion". Microb Pathog. 38 (2–3): 133–7. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2004.11.001. hdl:11576/2504278. PMID 15748815.

- ↑ Makino, Kozo; Kenshiro Oshima; Ken Kurokawa; et al. (March 1, 2003). "Genome sequence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a pathogenic mechanism distinct from that of V. cholerae". The Lancet. 361 (9359): 743–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12659-1. PMID 12620739. S2CID 23443158.

- ↑ Okada, Natsumi; Tetsuya Iida; Kwon-Sam Park; et al. (Feb 2009). "Identification and Characterization of a Novel Type III Secretion System in trh-positive Vibrio parahaemolyticus Strain TH3997 Reveal Genetic Lineage and Diversityt of Pathogenic Machinery beyond the Species Level". Infection and Immunity. 77 (2): 904–913. doi:10.1128/IAI.01184-08. PMC 2632016. PMID 19075025.

- ↑ Noriea, Nicholas; CN Johnson; KJ Griffitt; DJ Grimes (September 2010). "Distribution of type III secretion systems in 'Vibrio parahaemolyticus from the northern Gulf of Mexico". Journal of Applied Microbiology. 109 (3): 953–962. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2010.04722.x. PMID 20408916.

- ↑ Letchumanan, V; Chan, KG; Khan, TM; Bukhari, SI; Ab Mutalib, NS; Goh, BH; Lee, LH (2017). "Bile Sensing: The Activation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus Virulence". Frontiers in microbiology. 8: 728. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00728. PMID 28484445.

- ↑ Casey, Michael. "New Hampshire Looks for Answers Behind Oyster Outbreaks". R&D Magazine. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 6 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ Penland RL, Boniuk M, Wilhelmus KR (2000). "Vibrio ocular infections on the U.S. Gulf Coast". Cornea. 19 (1): 26–9. doi:10.1097/00003226-200001000-00006. PMID 10632004. S2CID 42510694.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kumazawa, NH; Kato, E; Takaba, T; Yokota, T (1988). "Survival of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in two gastropod molluscs, Clithon retropictus and Nerita albicilla". Nihon Juigaku Zasshi. The Japanese Journal of Veterinary Science. 50 (4): 918–24. doi:10.1292/jvms1939.50.918. PMID 3172602.

- ↑ "Cause Of EMS Shrimp Disease Identified". Gaalliance.org. Archived from the original on 2014-03-27. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

- ↑ "Vibrio parahaemolyticus and raw Pacific oysters from Coffin Bay, SA". Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ). Archived from the original on 2021-12-04. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

- ↑ "Coffin Bay Oysters Recalled". Government of South Australia. Archived from the original on 2021-12-04. Retrieved 2021-12-04.

External links

Data related to Vibrio parahaemolyticus at Wikispecies

Data related to Vibrio parahaemolyticus at Wikispecies- CDC Disease Info vibriop

- FDA Bad Bug Book entry on V. parahaemolyticus

- Type strain of Vibrio parahaemolyticus at BacDive - the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase Archived 2023-04-27 at the Wayback Machine