Listeriosis

| Listeriosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Listeria monocytogenes | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Diarrhea, fever[1] |

| Complications | Stillbirth, spontaneous abortion (pregnancy)[1] |

| Causes | Listeria monocytogenes[1] |

| Risk factors | Immunocompromised, pregnancy, extremes of age[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Culture of blood or spinal fluid[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Herpes simplex virus, mononucleosis, influenza[2] |

| Prevention | Safe food handling, avoiding unpasteurized milk[1] |

| Treatment | Ampicillin, gentamicin[3] |

| Frequency | 23,000 cases per year[4] |

| Deaths | 20% (severe disease)[1] |

Listeriosis is a bacterial infection that typically results in diarrhea, fever, and muscles aches.[1] Complications may include sepsis, meningitis, or encephalitis.[1] Onset of severe disease may take up to 4 weeks after exposure.[1] During pregnancy it may cause stillbirth, spontaneous abortion, preterm birth.[1]

It is most commonly caused by Listeria monocytogenes after eating contaminated food.[1] While exposure is common, severe disease is rare.[3] Those most commonly affected include the extremes of age, immunocompromised, and pregnant.[1] Diagnosis is by culturing the bacteria from blood or cerebrospinal fluid.[1] It is not picked up by routine stool culture.[3]

Treatment of those with positive cultures is typically with the antibiotics, ampicillin and gentamicin, for two to three weeks.[3] Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole may be used in those who are allergic to penicillin.[2] Prevention is by safe food handling, recalling contaminated food, and avoiding unpasteurized milk and cold deli meats.[1][2] The risk of death with severe disease is about 20%.[1]

Listeriosis resulted in about 23,000 cases globally in 2010.[4] In the United States it affects about 1,600 people per year and results in about 260 deaths.[1][3] Cases may occur as part of outbreaks of disease.[1] It was first discovered to be a foodborne illness in 1981.[2] Other animals may also be affected.[5]

Signs and symptoms

The disease primarily affects older adults, persons with weakened immune systems, pregnant women, and newborns. A person with listeriosis usually has fever and muscle aches, often preceded by diarrhea or other gastrointestinal symptoms. Almost everyone who is diagnosed with listeriosis has invasive infection . Disease may occur as much as two months after eating contaminated food.[6][7][8]

The symptoms vary with the infected person:

- High-risk people (immunocompromised) : Symptoms can include fever, muscle aches, headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, and convulsions.[9][2]

- Pregnant women: Pregnant women typically experience only a mild, flu-like illness. However, infections during pregnancy can lead to miscarriage, stillbirth, or life-threatening infection of the newborn.[8][2]

- Previously healthy people: People who were previously healthy but were exposed to a very large dose of Listeria can develop a non-invasive illness. Symptoms can include diarrhea and fever.[10]

If an animal has eaten food contaminated with Listeria and does not have any symptoms, most experts believe that no tests or treatment are needed, even for people at high risk for listeriosis.[11]

Cause

Listeria monocytogenes is ubiquitous in the environment. The main route of acquisition of Listeria is through the ingestion of contaminated food products. Listeria has been isolated from raw meat, dairy products, vegetables, fruit and seafood. Soft cheeses, unpasteurized milk and unpasteurised pâté are potential dangers; however, some outbreaks involving post-pasteurized milk have been reported.[12]

Rarely listeriosis may present involving the skin. This infection occurs after direct exposure to L. monocytogenes by intact skin and is largely confined to veterinarians who are handling diseased animals, most often after a listerial abortion.[13]

It can be more common in patients with hemochromatosis.[14]

-

Electron micrograph of Listeria monocytogenes bacterium in tissue

-

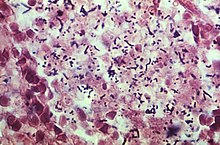

Photomicrograph reveals the presence of numerous Gram-positive, Listeria monocytogenes bacteria, harvested from the lung of a newborn with listeriosis.

Mechanism

Invasive infection by L. monocytogenes causes the disease listeriosis. When the infection is not invasive, any illness as a consequence of infection is termed febrile gastroenteritis. The manifestations of listeriosis include sepsis,[15] meningitis (or meningoencephalitis),[15] encephalitis,[16] corneal ulcer,[17] pneumonia,[18] myocarditis,[19] and intrauterine or cervical infections in pregnant women, which may result in spontaneous abortion or stillbirth.[20]

Surviving neonates of fetomaternal listeriosis may suffer granulomatosis infantiseptica — pyogenic granulomas distributed over the whole body — and may suffer from physical retardation. An early study suggested that L. monocytogenes is unique among Gram-positive bacteria in that it might possess lipopolysaccharide,[21] which serves as an endotoxin.

Later, it was found to not be a true endotoxin. Listeria cell walls consistently contain lipoteichoic acids, in which a glycolipid moiety, such as a galactosyl-glucosyl-diglyceride, is covalently linked to the terminal phosphomonoester of the teichoic acid. This lipid region anchors the polymer chain to the cytoplasmic membrane. These lipoteichoic acids resemble the lipopolysaccharides of Gram-negative bacteria in both structure and function, being the only amphipathic polymers at the cell surface.[22][23]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis, in Central nervous system infection cases, L. monocytogenes can often be cultured from the blood or from the CSF (cerebrospinal spinal fluid).[24] Testing is only required in those with symptoms.[1]

Classification

There are several distinct clinical syndromes:[25]

- Infection in pregnancy: Listeria can proliferate asymptomatically in the vagina and uterus. If the mother becomes symptomatic, it is usually in the third trimester. Symptoms include fever, myalgias, arthralgias and headache. Miscarriage, stillbirth and preterm labor are complications of this infection. Symptoms last 7–10 days.[26]

- Granulomatosis infantiseptica: An early-onset sepsis, with Listeria acquired in utero, results in premature birth. Listeria can be isolated in the placenta, blood, meconium, nose, ears, and throat. Another, late-onset meningitis is acquired through vaginal transmission, although it also has been reported with caesarean deliveries.[27][28][29]

- Central nervous system infection: Listeria has a predilection for the brain parenchyma, especially the brain stem, and the meninges. It can cause cranial nerve palsies, encephalitis, meningitis, meningoencephalitis and abscesses. Mental status changes are common. Seizures occur in at least 25% of patients.[30][31][2]

- Gastroenteritis: L. monocytogenes can produce food-borne diarrheal disease, which typically is noninvasive. The median incubation period is 21 days, with diarrhea lasting anywhere from 1–3 days. Affected people present with fever, muscle aches, gastrointestinal nausea or diarrhea, headache, stiff neck, confusion, loss of balance, or convulsions.[32][33][2]

Listeria has also been reported to colonize the hearts of some patients. The overall incidence of cardiac infections caused by Listeria is relatively low, with 7–10% of case reports indicating some form of heart involvement. There is some evidence that small subpopulations of clinical isolates are more capable of colonizing the heart throughout the course of infection, but cardiac manifestations are usually sporadic and may rely on a combination of bacterial factors and host predispositions, as they do with other strains of cardiotropic bacteria.[34]

Prevention

The main means of prevention is through the promotion of safe handling, cooking and consumption of food. This includes washing raw vegetables and cooking raw food thoroughly, as well as reheating leftover or ready-to-eat foods like hot dogs until steaming hot.[35]

Another aspect of prevention is advising high-risk groups such as pregnant women and immunocompromised patients to avoid unpasteurized pâtés and foods such as soft cheeses like feta, Brie, Camembert cheese, and bleu. Cream cheeses, yogurt, and cottage cheese are considered safe. In the United Kingdom, advice along these lines from the Chief Medical Officer posted in maternity clinics led to a sharp decline in cases of listeriosis in pregnancy in the late 1980s.[36]

Treatment

Bacteremia should be treated for 2 weeks, meningitis for 3 weeks, and brain abscess for at least 6 weeks. Ampicillin generally is considered antibiotic of choice; gentamicin is added frequently for its synergistic effects. Overall mortality rate is 20–30%; of all pregnancy-related cases, 22% resulted in fetal loss or neonatal death, but mothers usually survive.[37]

Epidemiology

Incidence in 2004–2005 was 2.5–3 cases per million population a year in the United States, where pregnant women accounted for 30% of all cases. [38] Of all nonperinatal infections, 70% occur in immunocompromised patients. Incidence in the U.S. has been falling since the 1990s, in contrast to Europe where changes in eating habits have led to an increase during the same time. In the EU, it has stabilized at around 5 cases per annum per million population, although the rate in each country contributing data to EFSA/ECDC varies greatly.[39]

Outbreaks

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) there are about 1,600 cases of listeriosis annually in the United States. Compared to 1996–1998, the incidence of listeriosis had declined by about 38% by 2003. However, illnesses and deaths continue to occur. On average from 1998 to 2008, 2.4 outbreaks per year were reported to the CDC. A large outbreak occurred in 2002, when 54 illnesses, 8 deaths, and 3 fetal deaths in 9 states were found to be associated with consumption of contaminated turkey deli meat.[40]

The 2008 Canadian listeriosis outbreak, an outbreak of listeriosis in Canada linked to a Maple Leaf Foods plant in Toronto, Ontario killed 22 people.[41]

On March 13, 2015, the CDC stated that State and local health officials, CDC, and FDA are collaborating to investigate an outbreak of Listeria.[42] The joint investigation found that certain Blue Bell brand ice cream products are the likely source for some or all of these illnesses. Upon further investigation the CDC claimed Blue Bell ice cream had evidence of listeria bacteria in its Oklahoma manufacturing plant as far back as March 2013, which led to 3 deaths in Kansas.[43]

On March 14, 2015, an outbreak of listeriosis in Kansas was linked to certain Blue Bell Ice Cream products (Blue Bell Chocolate Chip Country Cookies, Great Divide Bars, Sour Pop Green Apple Bars, Cotton Candy Bars, Scoops, Vanilla Stick Slices, Almond Bars, and No Sugar Added Moo Bars). Blue Bell, the nation's third most popular ice cream brand, says its regular Moo Bars were untainted, as were its ice cream varieties in three-gallon, half-gallon, quart, pint and single-serving containers and its take-home frozen snack novelties. It was the first outbreak of a foodborne illness in the company's history. The items came from the company's production facility located in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in Washington, D.C. The Atlanta-based U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), also a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), stated that all five of the sickened individuals, including the three who have died (60% mortality rate) were receiving treatment at the same Kansas hospital before developing the listeriosis, suggesting their infections with the Listeria bacteria were nosocomial (acquired, while eating the products, in the hospital). That might also help to explain the higher mortality rate in these cases (60%, versus the more normal 20%-30%): the people, who were all older (three of the five were women) were already hospitalized.[44][42][45]

On April 20, 2015, Blue Bell issued a voluntary recall of all its products, citing further internal testing that found Listeria monocytogenes in an additional half gallon of ice cream from the Brenham facility.[46]

2011 United States listeriosis outbreak

On September 14, 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration warned consumers not to eat cantaloupes shipped by Jensen Farms from Granada, Colorado due to a potential link to a multi-state outbreak of listeriosis. At that time Jensen Farms voluntarily recalled cantaloupes shipped from July 29 through September 10, and distributed to at least 17 states with possible further distribution. The CDC reported that at least 22 people in seven states had been infected as of September 14.[47]

On September 26, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that a total of 72 persons had been infected with the four outbreak-associated strains of Listeria monocytogenes which had been reported to the CDC from 18 states. All illnesses started on or after July 31, 2011 and by September 26, thirteen deaths had been reported: 2 in Colorado, 1 in Kansas, 1 in Maryland, 1 in Missouri, 1 in Nebraska, 4 in New Mexico, 1 in Oklahoma, and 2 in Texas.[48][49] On September 30, 2011, a random sample of romaine lettuce taken by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration tested positive for listeria on lettuce shipped on September 12 and 13 by an Oregon distributor to at least two other states—Washington and Idaho.[50]

By October 18, the CDC reported that 12 states are now linked to listeria in cantaloupe and that 123 people have been sickened and a total of 25 have died. While the tainted cantaloupes should be off store shelves by now, the number of illnesses may still continue to grow. The CDC confirmed a sixth death in Colorado and a second in New York; Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Maryland, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas and Wyoming have also reported deaths.[51]

A final count on December 8 put the death toll at 30: Colorado (8), Indiana (1), Kansas (3), Louisiana (2), Maryland (1), Missouri (3), Nebraska (1), New Mexico (5), New York (2), Oklahoma (1), Texas (2), and Wyoming (1). Among persons who died, ages ranged from 48 to 96 years, with a median age of 82.5 years. In addition, one woman pregnant at the time of illness had a miscarriage.[52]

2015-18 European listeriosis outbreak

On 5 July 2018 the Manchester Evening News reported that at least four major supermarket retailers had issued major product recalls as a result of a large supplier confirming possible contamination of frozen vegetables sourced from Hungary.[53] The supplier, Greenyard Frozen UK, reported to the UK's Food Standards Agency that the factory in which the food was processed had been shut down by the Hungarian Food Chain Safety Office,[54] after which the European Food Safety Authority and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control issued updates stating that at least five EU member states (UK, Austria, Denmark, Finland and Sweden) were affected. Between June 2015 and July 2018, nine people had reportedly died as a result of Listeriosis, of a total of forty seven confirmed cases.[55]

In an update on the EFSA website, it was stated that the contamination had supposedly been present since at least 2015, and as a result the Hungarian Food Chain Safety Office had prohibited the marketing of all affected frozen vegetables and frozen vegetable packs produced by the plant in Baja between August 2016 and June 2018.[56] This followed a previous abstract study that found the majority of L. monocytogenes isolates had been found in a 2017 sample of various frozen vegetables, with a minority found in a 2016 sample, and a miniscurity found in a 2018 sample. The study suggested that the strain identified (L. monocytogenes serogroup IVb, multi-locus sequence type 6 (ST6)) was likely persisting standard cleaning operations and disinfection procedures, and that since common production lines were in operation, cross-contamination was an additional concern.[57]

2017 United States listeriosis outbreak

In March 2017 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) started investigating an outbreak of listeriosis linked to the consumption of soft raw milk cheese made by Vulto Creamery that led to two deaths.[58][59] The investigation resulted in a recall of certain soft cheeses produced by the company.[59]

2017–18 South African listeriosis outbreak

In early December 2017 an outbreak of listeriosis was reported by the South African Department of Health. The outbreak, as at 8 January 2018, had killed 61 people and has been confirmed to have infected more than 748 people.[60]

On 15 February 2018—There have been 872 confirmed cases. The death toll rapidly rose from 107 to 164 deaths in just seven days. The KwaZulu-Natal figures are 62 confirmed cases, of which 6 have died.[61]

As of 4 March 2018, with 967 people infected and 180 deaths, this was the largest listeriosis outbreak in history.[62] The source was traced to processed meat products produced at a Tiger Brands Enterprise plant in Polokwane.[63]

2018 Australia listeriosis outbreak

On 2 March 2018 the New South Wales Food Authority confirmed that investigations into a listeriosis outbreak in rockmelons (cantaloupes) began in January.[64] The cantaloupes had infected people from Victoria, Queensland, New South Wales and Tasmania.[65]

As of 2 March 2018, 13 of 15 cases had been confirmed as originating from listeria infected cantaloupes, and of the 15 people infected, 3 had died.[66]

Later victims included a fourth person on 7 March,[67] and a Victorian man in his 80s on 16 March. A miscarriage was also linked to listeriosis.[68] Seventeen cases had been confirmed as of 7 March.[67]

In July 2018, a number of countries, including Australia, issued recalls of frozen vegetables due to Listeria.[69]

2019 Spain listeriosis outbreak

In August 2019, an outbreak was declared in several provinces in Andalusia, southern Spain, as a result of consumption of a contaminated batch of processed-meat products. As of 19 August 2019, 80 people were diagnosed and 56 were hospitalized (43 of them in the province of Seville),[70] As of 20 August, 114 people were diagnosed, and 18 pregnant woman in hospital, and the first confirmed death (a 90-year-old woman); [71] although the total figure of hospitalised reduced to 53.[72] In addition, eight miscarriages have been related to the outbreak. Spanish Minister of Health María Luisa Carcedo declared that the outbreak had expanded out of the Andalusian Autonomous Community,[73] with one confirmed case in Extremadura,[74] and five suspected cases in Extremadura and Madrid.[75] The Minister specified that, although new cases could appear as a consequence of the long incubation period, the contaminated product had been withdrawn totally.[76] As of 21 August 2019, 132 people were diagnosed and 23 pregnant woman in hospital.[77] On 22 August an international alert was declared.[78]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 "Frequently Asked Questions about Listeria". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 March 2018. Archived from the original on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Rogalla, Denver; Bomar, Paul A. (2022). "Listeria Monocytogenes". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Information for Health Professionals and Laboratories | Listeria | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 30 March 2021. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 de Noordhout CM, Devleesschauwer B, Angulo FJ, Verbeke G, Haagsma J, Kirk M, Havelaar A, Speybroeck N (November 2014). "The global burden of listeriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 14 (11): 1073–1082. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70870-9. PMC 4369580. PMID 25241232.

- ↑ Shamloo, E.; Hosseini, H.; Abdi Moghadam, Z.; Halberg Larsen, M.; Haslberger, A.; Alebouyeh, M. (2019). "Importance of Listeria monocytogenes in food safety: a review of its prevalence, detection, and antibiotic resistance". Iranian Journal of Veterinary Research. 20 (4): 241–254. ISSN 1728-1997. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ↑ "Learn about the symptoms of Listeria". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 3 May 2022. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ↑ Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (24 January 2022). "Listeria (Listeriosis)". FDA. Archived from the original on 16 July 2022. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Listeria and Pregnancy". www.acog.org. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ↑ Rivero, G. A.; Torres, H. A.; Rolston, K. V. I.; Kontoyiannis, D. P. (October 2003). "Listeria monocytogenes infection in patients with cancer". Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 47 (2): 393–398. doi:10.1016/s0732-8893(03)00116-0. ISSN 0732-8893. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2022.

- ↑ Matle, Itumeleng; Mbatha, Khanyisile R.; Madoroba, Evelyn (9 October 2020). "A review of Listeria monocytogenes from meat and meat products: Epidemiology, virulence factors, antimicrobial resistance and diagnosis". Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research. 87 (1). doi:10.4102/ojvr.v87i1.1869. ISSN 2219-0635. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2022."Non-invasive gastroenteritis can manifest in immunocompetent adults and usually causes atypical meningitis, septicaemia and febrile gastroenteritis characterised by fever and watery diarrhoea lasting for 2–3 days, which is often accompanied by headache and backache"

- ↑ "Multistate Outbreak of Listeriosis Linked to Whole Cantaloupes from Jensen Farms, Colorado". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 27, 2011. Archived from the original on January 4, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2003). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-8385-8529-9.

- ↑ Swaminathan B, Gerner-Smidt P (August 2007). "The epidemiology of human listeriosis". Microbes and Infection. 9 (10): 1236–43. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.011. PMC 358189. PMID 17720602.

- ↑ Mazza J (15 January 2002). Manual of Clinical Hematology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 127–. ISBN 9780781729802. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Gray ML, Killinger AH (June 1966). "Listeria monocytogenes and listeric infections". Bacteriological Reviews. 30 (2): 309–82. doi:10.1128/br.30.2.309-382.1966. PMC 440999. PMID 4956900.

- ↑ Armstrong RW, Fung PC (May 1993). "Brainstem encephalitis (rhombencephalitis) due to Listeria monocytogenes: case report and review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 16 (5): 689–702. doi:10.1093/clind/16.5.689. PMID 8507761.

- ↑ Holland S, Alfonso E, Gelender H, Heidemann D, Mendelsohn A, Ullman S, Miller D (1987). "Corneal ulcer due to Listeria monocytogenes". Cornea. 6 (2): 144–6. doi:10.1097/00003226-198706020-00008. PMID 3608514.

- ↑ Whitelock-Jones L, Carswell J, Rasmussen KC (February 1989). "Listeria pneumonia. A case report". South African Medical Journal = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Geneeskunde. 75 (4): 188–9. PMID 2919343.

- ↑ Paras, Molly L.; Khurshid, Shaan; Foldyna, Borek; Huang, Alex L.; Hohmann, Elizabeth L.; Cooper, Leslie T.; Christensen, Bianca B. (2022-04-27). "Case 13-2022: A 56-Year-Old Man with Myalgias, Fever, and Bradycardia". New England Journal of Medicine. 386 (17): 1647–1657. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpc2201233. S2CID 248414580. Archived from the original on 2022-05-02. Retrieved 2022-07-08.

- ↑ Pfaff, Nicole Franzen; Tillett, Jackie (April 2016). "Listeriosis and Toxoplasmosis in Pregnancy: Essentials for Healthcare Providers". The Journal of Perinatal & Neonatal Nursing. 30 (2): 131–138. doi:10.1097/JPN.0000000000000164. ISSN 1550-5073. Archived from the original on 30 May 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ↑ Wexler H, Oppenheim JD (March 1979). "Isolation, characterization, and biological properties of an endotoxin-like material from the gram-positive organism Listeria monocytogenes". Infection and Immunity. 23 (3): 845–57. doi:10.1128/iai.23.3.845-857.1979. PMC 414241. PMID 110684.

- ↑ Fiedler F (1988). "Biochemistry of the cell surface of Listeria strains: a locating general view". Infection. 16 Suppl 2 (S2): S92-7. doi:10.1007/BF01639729. PMID 3417357. S2CID 43624806.

- ↑ Farber JM, Peterkin PI (September 1991). "Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen". Microbiological Reviews. 55 (3): 476–511. doi:10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. PMC 372831. PMID 1943998.

- ↑ Mahon CR, Lehman DC, Manuselis G (25 March 2014). Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 357–. ISBN 978-0-323-29262-7. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ↑ Schlech, Walter F. (31 May 2019). "Epidemiology and Clinical Manifestations of Listeria monocytogenes Infection". Microbiology Spectrum. 7 (3): 7.3.3. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.GPP3-0014-2018. ISSN 2165-0497. Archived from the original on 24 May 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ↑ Craig, Amanda M.; Dotters-Katz, Sarah; Kuller, Jeffrey A.; Thompson, Jennifer L. (June 2019). "Listeriosis in Pregnancy: A Review". Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 74 (6): 362–368. doi:10.1097/OGX.0000000000000683. ISSN 1533-9866. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic Internal Medicine Board Review. Oxford University Press. 24 October 2019. p. 570. ISBN 978-0-19-093838-3. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ↑ Schmidt, Thomas M. (11 September 2019). Encyclopedia of Microbiology. Academic Press. p. 806. ISBN 978-0-12-811737-8. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ↑ Allerberger, Franz; Huhulescu, Steliana (4 March 2015). "Pregnancy related listeriosis: treatment and control". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 13 (3): 395–403. doi:10.1586/14787210.2015.1003809. ISSN 1478-7210. Archived from the original on 22 July 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ↑ Disson, Olivier; Lecuit, Marc (1 March 2012). "Targeting of the central nervous system by Listeria monocytogenes". Virulence. 3 (2): 213–221. doi:10.4161/viru.19586. ISSN 2150-5594. Archived from the original on 13 July 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ↑ Mylonakis, E.; Hohmann, E. L.; Calderwood, S. B. (September 1998). "Central nervous system infection with Listeria monocytogenes. 33 years' experience at a general hospital and review of 776 episodes from the literature". Medicine. 77 (5): 313–336. doi:10.1097/00005792-199809000-00002. ISSN 0025-7974. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ Ooi, Say Tat; Lorber, Bennett (1 May 2005). "Gastroenteritis due to Listeria monocytogenes". Clinical Infectious Diseases: An Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 40 (9): 1327–1332. doi:10.1086/429324. ISSN 1537-6591. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ↑ Ryser, Elliot T.; Marth, Elmer H. (27 March 2007). Listeria, Listeriosis, and Food Safety. CRC Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-4200-1518-8. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ Alonzo F, Bobo LD, Skiest DJ, Freitag NE (April 2011). "Evidence for subpopulations of Listeria monocytogenes with enhanced invasion of cardiac cells". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 60 (Pt 4): 423–34. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.027185-0. PMC 3133665. PMID 21266727.

- ↑ "Prevention—Listeriosis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on May 7, 2020. Retrieved September 29, 2011.

- ↑ Skinner R (August 1996). "Listeria: the state of the science Rome 29–30 June 1995 Session IV: country and organizational postures on Listeria monocytogenes in food Listeria: UK government's approach". Food Control. 7 (4–5): 245–247. doi:10.1016/S0956-7135(96)00049-7.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick J, Barrera J (February 2007). "Health authorities link 12 deaths to contaminated meat". Canwest News Service. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016.

- ↑ "Listeria". Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 2013-05-06. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ↑ European Food Safety Authority, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (December 2016). "EU summary report on zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks 2015". EFSA Journal. 14 (12): 4634. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4634.

- ↑ "Statistics—Listeriosis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ Weatherill S (2009). "Report of the Independent Investigator into the 2008 Listeriosis outbreak" (PDF). Government of Canada. p. vii. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "Multistate Outbreak of Listeriosis Linked to Blue Bell Creameries Products". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 June 2015. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ↑ Jalonick MC (7 May 2015). "Listeria Found in Blue Bell Ice Cream Plant in 2013". ABC News. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015.

- ↑ Wallace T, Clayton N (14 March 2015). "3 Kansas hospital patients die of ice cream-related illness". MSN. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ↑ "FDA Investigates Listeria monocytogenes in Ice Cream Products from Blue Bell Creameries". United States Food and Drug Administration. 13 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015.

- ↑ "Statement from Blue Bell CEO and President Paul Kruse". Blue Bell Creameries. 20 April 2015. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "FDA warns consumers not to eat Rocky Ford Cantaloupes shipped by Jensen Farms". Fda.gov. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ "CDC - Outbreaks Involving Listeriosis—Listeriosis". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on July 9, 2013. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Colorado cantaloupes kill up to 16 in listeria outbreak". BBC News. September 28, 2011. Archived from the original on May 31, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- ↑ "Listeria Found in Lettuce, Too". Abcnews.go.com. 2011-09-30. Archived from the original on 2013-07-30. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ "25 now dead in listeria outbreak in cantaloupe". .timesdispatch.com. Associated Press. October 18, 2011. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Multistate Outbreak of Listeriosis Linked to Whole Cantaloupes from Jensen Farms, Colorado". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ↑ "Full list of 43 frozen food products recalled by Tesco, Lidl, Aldi, Iceland and more after listeria outbreak". Manchester Evening News. 5 March 2018. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ↑ "Greenyard Frozen UK Ltd recalls various frozen vegetable products due to possible contamination with Listeria monocytogenes". Food Standards Agency. UKFSA. 5 July 2018. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ↑ "Nine deaths spark warning over cooking of frozen vegetables". Newcastle Evening Chronicle. 4 July 2018. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ↑ "Listeria monocytogenes: update on foodborne outbreak". European Food Safety Authority. 3 July 2018. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ↑ "Multi-country outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes serogroup IVb, multi-locus sequence type 6, infections linked to frozen corn and possibly to other frozen vegetables – first update". European Commission. Vol. 15, no. 7. European Food Safety Authority. 2 July 2018. doi:10.2903/sp.efsa.2018.EN-1448. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ↑ "CDC Investigating Listeria Outbreak Linked To Contaminated Cheese". Huffington Post. 10 March 2017. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "Listeriosis—USA (02): Fatal, Unpasteurized Soft Cheese, Aged 60 Days, Recall". ProMED-mail. 12 March 2017. Archived from the original on 13 March 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ↑ Mitchley A (8 January 2018). "Listeriosis now a notifiable disease, as death toll rises to 61". News24. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ↑ Knowler W (15 February 2018). "The listeriosis crisis goes from bad to worse". EastCoastLive. Archived from the original on 31 May 2021. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ↑ Spies D (13 January 2018). "WHO: South Africa's listeriosis outbreak 'largest ever'". News24. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ↑ Child K (4 March 2018). "Enterprise polony identified as source of listeria outbreak". TimesLIVE. Archived from the original on 2021-05-31. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ↑ Claughton D, Jeffery C, McCosker A (March 2018). "Listeria outbreak claims third victim as authority says investigation began in January". ABC Rural. Archived from the original on 2018-12-17. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ↑ Das, Arpita (14 February 2019). "Listeriosis in Australia - January to July 2018". Global Biosecurity. 1 (1). doi:10.31646/gbio.9. ISSN 2652-0036. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ↑ "Victorian becomes third person to die in rockmelon listeria outbreak". ABC Rural. 3 March 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-05-10. Retrieved 2021-06-22.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 "Australia's rockmelon listeria outbreak kills fourth person". The Guardian. 7 March 2018. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ "Fifth person dies in rockmelon listeria outbreak". ABC News. Australia. 16 March 2018. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ Whitworth, Joe (19 July 2018). "107 countries received frozen vegetables recalled for Listeria | Food Safety News". Food Safety News. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ↑ EFE (19 August 2019). "Aumentan a 56 los hospitalizados por listeriosis y la Junta espera más casos". El Mundo (in español). Unidad Editorial Información General, S.L.U. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ↑ Moreno, Silvia (20 August 2019). "Una anciana de 90 años muere por el brote de listeriosis y ya hay 18 embarazadas hospitalizadas". El Mundo (in español). Unidad Editorial Información General, S.L.U. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ↑ "Siguen 53 ingresados en Andalucía por listeria y son ya 23 las embarazadas". EFE (in español). 21 August 2019. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ "El Gobierno señala que la alerta sanitaria por listeriosis de la carne de 'La Mechá' afecta a toda España". El Mundo (in español). Unidad Editorial Información General, S.L.U. 20 August 2019. Archived from the original on 20 August 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ↑ "Alerta sanitaria: primer caso de listeriosis fuera de Andalucía por carne mechada contaminada". ABC (in español). Vocento. 19 August 2019. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ Saiz, Eva (20 August 2019). "Muere una anciana de 90 años por el brote de listeriosis en Andalucía". El País (in español). Prisa. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ "Retiran todos los productos 'La Mechá' cuya carne provocó el brote de listeriosis". La Vanguardia (in español). 21 August 2019. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ Europa Press (21 August 2019). "Aumentan a 132 los afectados por listeriosis en Andalucía y hay 23 embarazadas ingresadas". Ideal. Vocento. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- ↑ Saiz, Eva; Vázquez, Cristina; Güell, Oriol (22 August 2019). "España lanza una alerta internacional por el brote de listeriosis de Sevilla". El País (in español). Prisa. Archived from the original on 22 August 2019. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

External links

- CDC Listeriosis site Archived 2021-06-24 at the Wayback Machine

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |