Stevens–Johnson syndrome

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| Man with characteristic skin lesions of Stevens–Johnson syndrome | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Fever, skin blisters, skin peeling, painful skin, red eyes[1] |

| Complications | Dehydration, sepsis, pneumonia, multiple organ failure.[1] |

| Usual onset | Age < 30[2] |

| Causes | Certain medications, certain infections, unknown[2][1] |

| Risk factors | HIV/AIDS, systemic lupus erythematosus, genetics[1] |

| Diagnostic method | <10% of the skin involved, skin biopsy[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Chickenpox, staphylococcal epidermolysis, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, autoimmune bullous disease[3] |

| Treatment | Hospitalization, stopping the cause[2] |

| Medication | Pain medication, antihistamines, antibiotics, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulins[2] |

| Prognosis | Mortality ~7.5%[1][4] |

| Frequency | 1–2 per million per year (together with TEN)[1] |

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a type of severe skin reaction.[1] Together with toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens–Johnson/toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN), it forms a spectrum of disease, with SJS being less severe.[1][3] Erythema multiforme (EM) is generally considered a separate condition.[5] Early symptoms of SJS include fever and flu-like symptoms.[1] A few days later, the skin begins to blister and peel, forming painful raw areas.[1] Mucous membranes, such as the mouth, are also typically involved.[1] Complications include dehydration, sepsis, pneumonia and multiple organ failure.[1]

The most common cause is certain medications such as lamotrigine, carbamazepine, allopurinol, sulfonamide antibiotics and nevirapine.[1] Other causes can include infections such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae and cytomegalovirus, or the cause may remain unknown.[2][1] Risk factors include HIV/AIDS and systemic lupus erythematosus.[1]

The diagnosis of Stevens–Johnson syndrome is based on involvement of less than 10% of the skin.[2] It is known as TEN when more than 30% of the skin is involved and considered an intermediate form when 10–30% is involved.[3] SJS/TEN reactions are believed to follow a type IV hypersensitivity mechanism.[6] It is also included with drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS syndrome), acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) and toxic epidermal necrolysis in a group of conditions known severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs).[7]

Treatment typically takes place in hospital such as in a burn unit or intensive care unit.[2] Efforts may include stopping the cause, pain medication, antihistamines, antibiotics, intravenous immunoglobulins or corticosteroids.[2] Together with TEN, SJS affects 1 to 2 people per million per year.[1] Typical onset is under the age of 30.[2] Skin usually regrows over two to three weeks; however, complete recovery can take months.[2] Overall, the risk of death with SJS is 5 to 10%.[1][4]

Signs and symptoms

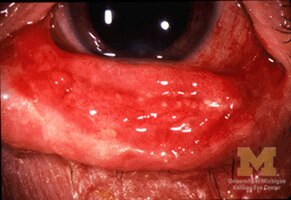

SJS usually begins with fever, sore throat, and fatigue, which is commonly misdiagnosed and therefore treated with antibiotics. SJS, SJS/TEN, and TEN are often heralded by fever, sore throat, cough, and burning eyes for 1 to 3 days.[8] Patients with these disorders frequently experience burning pain of their skin at the start of disease.[8] Ulcers and other lesions begin to appear in the mucous membranes, almost always in the mouth and lips, but also in the genital and anal regions. Those in the mouth are usually extremely painful and reduce the patient's ability to eat or drink. Conjunctivitis occurs in about 30% of children who develop SJS.[9] A rash of round lesions about an inch across arises on the face, trunk, arms and legs, and soles of the feet, but usually not the scalp.[10]

-

Stevens Johnson syndrome

-

Stevens Johnson syndrome

-

Mucosal desquamation in a person with Stevens–Johnson syndrome

-

Inflammation and peeling of the lips—with sores presenting on the tongue and the mucous membranes in SJS.

-

Conjunctivitis in SJS

Causes

SJS is thought to arise from a disorder of the immune system.[10] The immune reaction can be triggered by drugs or infections.[11] Genetic factors are associated with a predisposition to SJS.[12] The cause of SJS is unknown in one-quarter to one-half of cases.[12] SJS, SJS/TEN, and TEN are considered a single disease with common causes and mechanisms.[8]

Individuals expressing certain human leukocyte antigen (i.e. HLA) serotypes (i.e. genetic alleles), genetical-based T cell receptors, or variations in their efficiency to absorb, distribute to tissues, metabolize, or excrete (this combination is termed ADME) a drug are predisposed to develop SJS.

Medications

Although SJS can be caused by viral infections and malignancies, the main cause is medications.[13] A leading cause appears to be the use of antibiotics, particularly sulfa drugs.[12][14] Between 100 and 200 different drugs may be associated with SJS.[15] No reliable test exists to establish a link between a particular drug and SJS for an individual case.[13] Determining what drug is the cause is based on the time interval between first use of the drug and the beginning of the skin reaction. Drugs discontinued more than 1 month prior to onset of mucocutaneous physical findings are highly unlikely to cause SJS and TEN.[8] SJS and TEN most often begin between 4 and 28 days after culprit drug administration.[8] A published algorithm (ALDEN) to assess drug causality gives structured assistance in identifying the responsible medication.[13][16]

SJS may be caused by the medications rivaroxaban,[17] vancomycin, allopurinol, valproate, levofloxacin, diclofenac, etravirine, isotretinoin, fluconazole,[18] valdecoxib, sitagliptin, oseltamivir, penicillins, barbiturates, sulfonamides, phenytoin, azithromycin, oxcarbazepine, zonisamide, modafinil,[19] lamotrigine, nevirapine,[8] pyrimethamine, ibuprofen,[20] ethosuximide, carbamazepine, bupropion, telaprevir,[21][22] and nystatin.[23][24]

Medications that have traditionally been known to lead to SJS, erythema multiforme, and toxic epidermal necrolysis include sulfonamide antibiotics,[8] penicillin antibiotics, cefixime (antibiotic), barbiturates (sedatives), lamotrigine, phenytoin (e.g., Dilantin) (anticonvulsants) and trimethoprim. Combining lamotrigine with sodium valproate increases the risk of SJS.[25]

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a rare cause of SJS in adults; the risk is higher for older patients, women, and those initiating treatment.[26] Typically, the symptoms of drug-induced SJS arise within a week of starting the medication. Similar to NSAIDs, paracetamol (acetaminophen) has also caused rare cases[27][28] of SJS. People with systemic lupus erythematosus or HIV infections are more susceptible to drug-induced SJS.[10]

Infections

The second most common cause of SJS and TEN is infection, particularly in children. This includes upper respiratory infections, otitis media, pharyngitis, and Epstein–Barr virus, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and cytomegalovirus infections. The routine use of medicines such as antibiotics, antipyretics and analgesics to manage infections can make it difficult to identify if cases were caused by the infection or medicines taken.[29]

Viral diseases reported to cause SJS include: herpes simplex virus (possibly; is debated), AIDS, coxsackievirus, influenza, hepatitis, and mumps.[12]

In pediatric cases, Epstein-Barr virus and enteroviruses have been associated with SJS.[12]

Recent upper respiratory tract infections have been reported by more than half of patients with SJS.[12]

Bacterial infections linked to SJS include group A beta-hemolytic streptococci, diphtheria, brucellosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, mycobacteria, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, rickettsial infections, tularemia, and typhoid.[12]

Fungal infections with coccidioidomycosis, dermatophytosis and histoplasmosis are also considered possible causes.[12] Malaria and trichomoniasis, protozoal infections, have also been reported as causes.[12]

Pathophysiology

SJS is a type IV hypersensitivity reaction in which a drug or its metabolite stimulates cytotoxic T cells (i.e. CD8+ T cells) and T helper cells (i.e. CD4+ T cells) to initiate autoimmune reactions that attack self tissues. In particular, it is a type IV, subtype IVc, delayed hypersensitivity reaction dependent in part on the tissue-injuring actions of natural killer cells.[30] This contrasts with the other types of SCARs disorders, i.e., the DRESS syndrome which is a Type IV, Subtype IVb, hypersensitivity drug reaction dependent in part on the tissue-injuring actions of eosinophils[30][31] and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis which is a Type IV, subtype IVd, hypersensitivity reaction dependent in part on the tissue-injuring actions of neutrophils.[30][32]

Like other SCARs-inducing drugs, SJS-inducing drugs or their metabolites stimulate CD8+ T cells or CD4+ T cells to initiate autoimmune responses. Studies indicate that the mechanism by which a drug or its metabolites accomplishes this involves subverting the antigen presentation pathways of the innate immune system. The drug or metabolite covalently binds with a host protein to form a non-self, drug-related epitope. An antigen presenting cell (APC) takes up these alter proteins; digests them into small peptides; places the peptides in a groove on the human leukocyte antigen (i.e. HLA) component of their major histocompatibility complex (i.e. MHC); and presents the MHC-associated peptides to T-cell receptors on CD8+ T cells or CD4+ T cells. Those peptides expressing a drug-related, non-self epitope on one of their various HLA protein forms (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DM, HLA-DO, HLA-DP, HLA-DQ, or HLA-DR) can bind to a T-cell receptor and thereby stimulate the receptor-bearing parent T cell to initiate attacks on self tissues. Alternatively, a drug or its metabolite may stimulate these T cells by inserting into the groove on a HLA protein to serve as a non-self epitope or bind outside of this groove to alter a HLA protein so that it forms a non-self epitope. In all these cases, however, a non-self epitope must bind to a specific HLA serotype (i.e. variation) in order to stimulate T cells. Since the human population expresses some 13,000 different HLA serotypes while an individual expresses only a fraction of them and since a SJS-inducing drug or metabolite interacts with only one or a few HLA serotypes, a drug's ability to induce SCARs is limited to those individuals who express HLA serotypes targeted by the drug or its metabolite.[33][34] Accordingly, only rare individuals are predisposed to develop a SCARs in response to a particular drug on the bases of their expression of HLA serotypes:[35] Studies have identified several HLA serotypes associated with development of SJS, SJS/TEN, or TEN in response to certain drugs.[30][36] In general, these associations are restricted to the cited populations.[37]

In some East Asian populations studied (Han Chinese and Thai), carbamazepine- and phenytoin-induced SJS is strongly associated with HLA-B*1502 (HLA-B75), an HLA-B serotype of the broader serotype HLA-B15.[38][39][40] A study in Europe suggested the gene marker is only relevant for East Asians.[41][42] This has clinical relevance as it is agreed upon that prior to starting a medication such as allopurinol in a patient of Chinese descent, HLA-B*58:01 testing should be considered.[8]

Based on the Asian findings, similar studies in Europe showed 61% of allopurinol-induced SJS/TEN patients carried the HLA-B58 (phenotype frequency of the B*5801 allele in Europeans is typically 3%). One study concluded: "Even when HLA-B alleles behave as strong risk factors, as for allopurinol, they are neither sufficient nor necessary to explain the disease."[43]

Other HLA associations with the development of SJS, SJS/TEN, or TEN and the intake of specific drugs as determined in certain populations are given in HLA associations with SCARs.

T-cell receptors

In addition to acting through HLA proteins to bind with a T-cell receptor, a drug or its metabolite may bypass HLA proteins to bind directly to a T-cell receptor and thereby stimulate CD8+ T or CD4+ T cells to initiate autoimmune responses. In either case, this binding appears to develop only on certain T cell receptors. Since the genes for these receptors are highly edited, i.e. altered to encode proteins with different amino acid sequences, and since the human population may express more than 100 trillion different (i.e. different amino acid sequences) T-cell receptors while an individual express only a fraction of these, a drug's or its metabolite's ability to induce the DRESS syndrome by interacting with a T cell receptor is limited to those individuals whose T cells express a T cell receptor(s) that can interact with the drug or its metabolite.[33][44] Thus, only rare individuals are predisposed to develop SJS in response to a particular drug on the bases of their expression of specific T-cell receptor types.[35] While the evidence supporting this T-cell receptor selectivity is limited, one study identified the preferential presence of the TCR-V-b and complementarity-determining region 3 in T-cell receptors found on the T cells in the blisters of patients with allopurinol-induced DRESS syndrome. This finding is compatible with the notion that specific types of T cell receptors are involved in the development of specific drug-induced SCARs.[36]

ADME

Variations in ADME, i.e. an individual's efficiency in absorbing, tissue-distributing, metabolizing, or excreting a drug, have been found to occur in various severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARS) as well as other types of adverse drug reactions.[45] These variations influence the levels and duration of a drug or its metabolite in tissues and thereby impact the drug's or metabolite's ability to evoke these reactions.[7] For example, CYP2C9 is an important drug-metabolizing cytochrome P450; it metabolizes and thereby inactivates phenytoin. Taiwanese, Japanese, and Malaysian individuals expressing the CYP2C9*3[46] variant of CYP2C9, which has reduced metabolic activity compared to the wild type (i.e. CYP2c9*1) cytochrome, have increased blood levels of phenytoin and a high incidence of SJS (as well as SJS/TEN and TEN) when taking the drug.[7][47] In addition to abnormalities in drug-metabolizing enzymes, dysfunctions of the kidney, liver, or GI tract which increase a SCARs-inducing drug or metabolite levels are suggested to promote SCARs responses.[7][4] These ADME abnormalities, it is also suggested, may interact with particular HLA proteins and T cell receptors to promote a SCARs disorder.[7][48]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is based on involvement of less than 10% of the skin.[2] It is known as TEN when more than 30% of the skin is involved and an intermediate form with 10 to 30% involvement.[3] A positive Nikolsky's sign is helpful in the diagnosis of SJS and TEN.[8] A skin biopsy is helpful, but not required, to establish a diagnosis of SJS and TEN.[8]

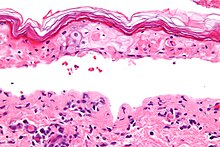

Pathology

SJS, like TEN and erythema multiforme, is characterized by confluent epidermal necrosis with minimal associated inflammation. The acuity is apparent from the (normal) basket weave-like pattern of the stratum corneum.

Classification

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) is a milder form of toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).[49] These conditions were first recognised in 1922.[26] A classification first published in 1993, that has been adopted as a consensus definition, identifies Stevens–Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and SJS/TEN overlap. All three are part of a spectrum of severe cutaneous reactions (SCAR) which affect skin and mucous membranes.[13] The distinction between SJS, SJS/TEN overlap, and TEN is based on the type of lesions and the amount of the body surface area with blisters and erosions.[13] It is agreed that the most reliable method to classify EM, SJS, and TEN is based on lesion morphology and extent of epidermal detachment.[8] Blisters and erosions cover between 3% and 10% of the body in SJS, 11–30% in SJS/TEN overlap, and over 30% in TEN.[13] The skin pattern most commonly associated with SJS is widespread, often joined or touching (confluent), papuric spots (macules) or flat small blisters or large blisters which may also join together.[13] These occur primarily on the torso.[13]

SJS, TEN, and SJS/TEN overlap can be mistaken for erythema multiforme.[50] Erythema multiforme, which is also within the SCAR spectrum, differs in clinical pattern and etiology.[13] Although both SJS and TEN can also be caused by infections, they are most often adverse effects of medications.[13]

Prevention

Screening individuals for certain predisposing gene variants before initiating treatment with particular SJS-, TEN/SJS-, or TEN-inducing drugs is recommended or under study. These recommendations are typically limited to specific populations that show a significant chance of having the indicated gene variant since screening of populations with extremely low incidences of expressing the variant is considered cost-ineffective.[51] Individuals expressing the HLA allele associated with sensitivity to an indicated drug should not be treated with the drug. These recommendations include the following.[7][52] Before treatment with carbamazepine, the Taiwan and USA Food and Drug Administrations recommend screening for HLA-B*15:02 in certain Asian groups. This has been implemented in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and many medical centers in Thailand and Mainland China. Before treatment with allopurinol, the American College of Rheumatology guidelines for managing gout recommend HLA-B*58:01 screening. This is provided in many medical centers in Taiwan, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Mainland China. Before treatment with abacavir, the USA Food and Drug Administration recommends screening for HLA-B*57:01 in Caucasian populations. This screening is widely implemented.[citation needed] It has also been suggested[by whom?] that all individuals found to express this HLA serotype avoid treatment with abacovir. Current trials are underway in Taiwan to define the cost-effectiveness of avoiding phenytoin in SJS, SJS/TEN, and TEN for individuals expressing the CYP2C9*3 allele of CYP2C9.[52]

Treatment

SJS constitutes a dermatological emergency. Patients with documented Mycoplasma infections can be treated with oral macrolide or oral doxycycline.[10]

Initially, treatment is similar to that for patients with thermal burns, and continued care can only be supportive (e.g. intravenous fluids and nasogastric or parenteral feeding) and symptomatic (e.g., analgesic mouth rinse for mouth ulcer). Dermatologists and surgeons tend to disagree about whether the skin should be debrided.[10]

Beyond this kind of supportive care, no treatment for SJS is accepted. Treatment with corticosteroids is controversial. Early retrospective studies suggested corticosteroids increased hospital stays and complication rates. No randomized trials of corticosteroids were conducted for SJS, and it can be managed successfully without them.[10]

Other agents have been used, including cyclophosphamide and ciclosporin, but none has exhibited much therapeutic success. Intravenous immunoglobulin treatment has shown some promise in reducing the length of the reaction and improving symptoms. Other common supportive measures include the use of topical pain anesthetics and antiseptics, maintaining a warm environment, and intravenous analgesics.

An ophthalmologist should be consulted immediately, as SJS frequently causes the formation of scar tissue inside the eyelids, leading to corneal vascularization, impaired vision, and a host of other ocular problems. Those with chronic ocular surface disease caused by SJS may find some improvement with PROSE treatment (prosthetic replacement of the ocular surface ecosystem treatment).[53]

Prognosis

SJS (with less than 10% of body surface area involved) has a mortality rate of around 5%. The mortality for toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is 30–40%. The risk for death can be estimated using the SCORTEN scale, which takes a number of prognostic indicators into account.[54] It is helpful to calculate a SCORTEN within the first 3 days of hospitalization.[8] Other outcomes include organ damage/failure, cornea scratching, and blindness.[citation needed]. Restrictive lung disease may develop in patients with SJS and TEN after initial acute pulmonary involvement.[8] Patients with SJS or TEN caused by a drug have a better prognosis the earlier the causative drug is withdrawn.[8]

Epidemiology

SJS is a rare condition, with a reported incidence of around 2.6[10] to 6.1[26] cases per million people per year. In the United States, about 300 new diagnoses are made each year. The condition is more common in adults than in children.

History

SJS is named for Albert Mason Stevens and Frank Chambliss Johnson, American pediatricians who jointly published a description of the disorder in the American Journal of Diseases of Children in 1922.[55][56]

Notable cases

- Ab-Soul, American hip hop recording artist and member of Black Hippy[57]

- Padma Lakshmi, actress, model, television personality, and cookbook writer[58]

- Manute Bol, former NBA player. Bol died from complications of Stevens–Johnson syndrome as well as kidney failure.[59]

- Gene Sauers, three-time PGA Tour winner[60]

- Samantha Reckis, a seven-year-old Plymouth, Massachusetts girl who lost the skin covering 95% of her body after taking children's Motrin in 2003. In 2013, a jury awarded her $63M in a lawsuit against Johnson & Johnson, one of the largest lawsuits of its kind.[61] The decision was upheld in 2015.[62]

- Karen Elaine Morton, a model and actress who appeared in Tommy Tutone's "867-5309/Jenny" video and was Playmate of the Month in the July 1978 issue of Playboy Magazine.[63]

Research

In 2015, the NIH and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) organized a workshop entitled “Research Directions in Genetically-Mediated Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis”.[8]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 "Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis". Genetics Home Reference. July 2015. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 "Stevens-Johnson syndrome". GARD. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Orphanet: Toxic epidermal necrolysis". Orphanet. November 2008. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Lerch M, Mainetti C, Terziroli Beretta-Piccoli B, Harr T (2017). "Current Perspectives on Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis". Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 54 (1): 147–176. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8654-z. PMID 29188475.

- ↑ Schwartz, RA; McDonough, PH; Lee, BW (August 2013). "Toxic epidermal necrolysis: Part I. Introduction, history, classification, clinical features, systemic manifestations, etiology, and immunopathogenesis". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 69 (2): 173.e1–13, quiz 185–6. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.003. PMID 23866878.

- ↑ Hyzy, Robert C. (2017). Evidence-Based Critical Care: A Case Study Approach. Springer. p. 761. ISBN 9783319433417. Archived from the original on 4 February 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Adler NR, Aung AK, Ergen EN, Trubiano J, Goh MS, Phillips EJ (2017). "Recent advances in the understanding of severe cutaneous adverse reactions". The British Journal of Dermatology. 177 (5): 1234–1247. doi:10.1111/bjd.15423. PMC 5582023. PMID 28256714.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 Maverakis, Emanual; Wang, Elizabeth A.; Shinkai, Kanade; Mahasirimongkol, Surakameth; Margolis, David J.; Avigan, Mark; Chung, Wen-Hung; Goldman, Jennifer; Grenade, Lois La (2017). "Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Standard Reporting and Evaluation Guidelines" (PDF). JAMA Dermatology. 153 (6): 587–592. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.0160. PMID 28296986. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ↑ Adwan MH (January 2017). "Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) Syndrome and the Rheumatologist". Current Rheumatology Reports. 19 (1): 3. doi:10.1007/s11926-017-0626-z. PMID 28138822.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 Tigchelaar, H.; Kannikeswaran, N.; Kamat, D. (December 2008). "Stevens–Johnson Syndrome: An intriguing diagnosis". pediatricsconsultantlive.com. UBM Medica. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012.

- ↑ Tan SK, Tay YK; Tay (2012). "Profile and pattern of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis in a general hospital in Singapore: Treatment outcomes". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 92 (1): 62–6. doi:10.2340/00015555-1169. PMID 21710108.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Foster, C. Stephen; Ba-Abbad, Rola; Letko, Erik; Parrillo, Steven J.; et al. (12 August 2013). Roy, Sr., Hampton (article editor). "Stevens-Johnson Syndrome". Medscape Reference. Etiology. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 13.9 Mockenhaupt M (2011). "The current understanding of Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis". Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 7 (6): 803–15. doi:10.1586/eci.11.66. PMID 22014021.

- ↑ Teraki Y, Shibuya M, Izaki S; Shibuya; Izaki (2010). "Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis due to anticonvulsants share certain clinical and laboratory features with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome, despite differences in cutaneous presentations". Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 35 (7): 723–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03718.x. PMID 19874350.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Cooper KL (2012). "Drug reaction, skin care, skin loss". Crit Care Nurse. 32 (4): 52–9. doi:10.4037/ccn2012340. PMID 22855079.

- ↑ Sassolas B, Haddad C, Mockenhaupt M, Dunant A, Liss Y, Bork K, Haustein UF, Vieluf D, Roujeau JC, Le Louet H; Haddad; Mockenhaupt; Dunant; Liss; Bork; Haustein; Vieluf; Roujeau; Le Louet (2010). "ALDEN, an algorithm for assessment of drug causality in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: Comparison with case-control analysis". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 88 (1): 60–8. doi:10.1038/clpt.2009.252. PMID 20375998. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Scientific conclusions and grounds for the variation to the terms of the marketing authorisation(s)" (PDF) (data sheet). European Medicines Agency. 6 April 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ↑ "Diflucan One" (data sheet). Medsafe; New Zealand Ministry of Health. 29 April 2008. Archived from the original on 3 June 2010.

- ↑ "Provigil (modafinil) Tablets". MedWatch. US Food and Drug Administration. 24 October 2007. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013.

- ↑ Raksha MP, Marfatia YS; Marfatia (2008). "Clinical study of cutaneous drug eruptions in 200 patients". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 74 (1): 80. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.38431. PMID 18193504. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- ↑ "Incivek prescribing information" (PDF) (package insert). Vertex Pharmaceuticals. December 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 March 2013.

- ↑ Surovik J, Riddel C, Chon SY; Riddel; Chon (2010). "A case of bupropion-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome with acute psoriatic exacerbation". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology: JDD. 9 (8): 1010–2. PMID 20684153.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Fagot JP, Mockenhaupt M, Bouwes-Bavinck JN, Naldi L, Viboud C, Roujeau JC; Mockenhaupt; Bouwes-Bavinck; Naldi; Viboud; Roujeau; Euroscar Study (2001). "Nevirapine and the risk of Stevens–Johnson syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis". AIDS. 15 (14): 1843–8. doi:10.1097/00002030-200109280-00014. PMID 11579247.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Devi K, George S, Criton S, Suja V, Sridevi PK; George; Criton; Suja; Sridevi (2005). "Carbamazepine – The commonest cause of toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome: A study of 7 years". Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 71 (5): 325–8. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.16782. PMID 16394456.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kocak S, Girisgin SA, Gul M, Cander B, Kaya H, Kaya E (2007). "Stevens-Johnson syndrome due to concomitant use of lamotrigine and valproic acid". Am J Clin Dermatol. 8 (2): 107–11. doi:10.2165/00128071-200708020-00007. PMID 17428116.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Ward KE, Archambault R, Mersfelder TL; Archambault; Mersfelder (2010). "Severe adverse skin reactions to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: A review of the literature". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 67 (3): 206–213. doi:10.2146/ajhp080603. PMID 20101062.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Khawaja A, Shahab A, Hussain SA; Shahab; Hussain (2012). "Acetaminophen induced Steven Johnson syndrome-Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis overlap". Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 62 (5): 524–7. PMID 22755330. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Trujillo C, Gago C, Ramos S; Gago; Ramos (2010). "Stevens-Jonhson syndrome after acetaminophen ingestion, confirmed by challenge test in an eleven-year-old patient". Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 38 (2): 99–100. doi:10.1016/j.aller.2009.06.009. PMID 19875224.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Bentley, John; Sie, David (8 October 2014). "Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis". The Pharmaceutical Journal. 293 (7832). Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Hoetzenecker W, Nägeli M, Mehra ET, Jensen AN, Saulite I, Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Guenova E, Cozzio A, French LE (January 2016). "Adverse cutaneous drug eruptions: current understanding". Seminars in Immunopathology. 38 (1): 75–86. doi:10.1007/s00281-015-0540-2. PMID 26553194.

- ↑ Uzzaman A, Cho SH (2012). "Chapter 28: Classification of hypersensitivity reactions". Allergy and Asthma Proceedings. 33 Suppl 1 (3): S96–9. doi:10.2500/aap.2012.33.3561. PMID 22794701.

- ↑ Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N (2016). "Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis: Pathogenesis, Genetic Background, Clinical Variants and Therapy". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 17 (8): 1214. doi:10.3390/ijms17081214. PMC 5000612. PMID 27472323.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Duong TA, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Wolkenstein P, Chosidow O (2017). "Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs". Lancet. 390 (10106): 1996–2011. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30378-6. PMID 28476287.

- ↑ Bachelez H (January 2018). "Pustular psoriasis and related pustular skin diseases". The British Journal of Dermatology. 178 (3): 614–618. doi:10.1111/bjd.16232. PMID 29333670.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Pichler WJ, Hausmann O (2016). "Classification of Drug Hypersensitivity into Allergic, p-i, and Pseudo-Allergic Forms". International Archives of Allergy and Immunology. 171 (3–4): 166–179. doi:10.1159/000453265. PMID 27960170.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Wang CW, Dao RL, Chung WH (2016). "Immunopathogenesis and risk factors for allopurinol severe cutaneous adverse reactions". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 16 (4): 339–45. doi:10.1097/ACI.0000000000000286. PMID 27362322.

- ↑ Fan WL, Shiao MS, Hui RC, Su SC, Wang CW, Chang YC, Chung WH (2017). "HLA Association with Drug-Induced Adverse Reactions". Journal of Immunology Research. 2017: 3186328. doi:10.1155/2017/3186328. PMC 5733150. PMID 29333460.

- ↑ Chung WH, Hung SI, Hong HS, Hsih MS, Yang LC, Ho HC, Wu JY, Chen YT; Hung; Hong; Hsih; Yang; Ho; Wu; Chen (2004). "Medical genetics: A marker for Stevens–Johnson syndrome". Brief Communications. Nature. 428 (6982): 486. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..486C. doi:10.1038/428486a. PMID 15057820.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Locharernkul C, Loplumlert J, Limotai C, Korkij W, Desudchit T, Tongkobpetch S, Kangwanshiratada O, Hirankarn N, Suphapeetiporn K, Shotelersuk V; Loplumlert; Limotai; Korkij; Desudchit; Tongkobpetch; Kangwanshiratada; Hirankarn; Suphapeetiporn; Shotelersuk (2008). "Carbamazepine and phenytoin induced Stevens–Johnson syndrome is associated with HLA-B*1502 allele in Thai population". Epilepsia. 49 (12): 2087–91. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01719.x. PMID 18637831.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Man CB, Kwan P, Baum L, Yu E, Lau KM, Cheng AS, Ng MH; Kwan; Baum; Yu; Lau; Cheng; Ng (2007). "Association between HLA-B*1502 allele and antiepileptic drug-induced cutaneous reactions in Han Chinese". Epilepsia. 48 (5): 1015–8. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01022.x. PMID 17509004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Alfirevic A, Jorgensen AL, Williamson PR, Chadwick DW, Park BK, Pirmohamed M; Jorgensen; Williamson; Chadwick; Park; Pirmohamed (2006). "HLA-B locus in Caucasian patients with carbamazepine hypersensitivity". Pharmacogenomics. 7 (6): 813–8. doi:10.2217/14622416.7.6.813. PMID 16981842.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Lonjou C, Thomas L, Borot N, Ledger N, de Toma C, LeLouet H, Graf E, Schumacher M, Hovnanian A, Mockenhaupt M, Roujeau JC; Thomas; Borot; Ledger; De Toma; Lelouet; Graf; Schumacher; Hovnanian; Mockenhaupt; Roujeau; Regiscar (2006). "A marker for Stevens–Johnson syndrome ...: Ethnicity matters". The Pharmacogenomics Journal. 6 (4): 265–8. doi:10.1038/sj.tpj.6500356. PMID 16415921.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Lonjou C, Borot N, Sekula P, Ledger N, Thomas L, Halevy S, Naldi L, Bouwes-Bavinck JN, Sidoroff A, de Toma C, Schumacher M, Roujeau JC, Hovnanian A, Mockenhaupt M; Borot; Sekula; Ledger; Thomas; Halevy; Naldi; Bouwes-Bavinck; Sidoroff; De Toma; Schumacher; Roujeau; Hovnanian; Mockenhaupt; Regiscar Study (2008). "A European study of HLA-B in Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis related to five high-risk drugs". Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 18 (2): 99–107. doi:10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282f3ef9c. PMID 18192896. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Garon SL, Pavlos RK, White KD, Brown NJ, Stone CA, Phillips EJ (September 2017). "Pharmacogenomics of off-target adverse drug reactions". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 83 (9): 1896–1911. doi:10.1111/bcp.13294. PMC 5555876. PMID 28345177.

- ↑ Alfirevic A, Pirmohamed M (January 2017). "Genomics of Adverse Drug Reactions". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 38 (1): 100–109. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2016.11.003. PMID 27955861.

- ↑ snpdev. "Reference SNP (refSNP) Cluster Report: rs1057910 ** With drug-response allele **". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ↑ Chung WH, Chang WC, Lee YS, Wu YY, Yang CH, Ho HC, Chen MJ, Lin JY, Hui RC, Ho JC, Wu WM, Chen TJ, Wu T, Wu YR, Hsih MS, Tu PH, Chang CN, Hsu CN, Wu TL, Choon SE, Hsu CK, Chen DY, Liu CS, Lin CY, Kaniwa N, Saito Y, Takahashi Y, Nakamura R, Azukizawa H, Shi Y, Wang TH, Chuang SS, Tsai SF, Chang CJ, Chang YS, Hung SI (August 2014). "Genetic variants associated with phenytoin-related severe cutaneous adverse reactions". JAMA. 312 (5): 525–34. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.7859. PMID 25096692.

- ↑ Chung WH, Wang CW, Dao RL (2016). "Severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions". The Journal of Dermatology. 43 (7): 758–66. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13430. PMID 27154258.

- ↑ Rehmus, W. E. (November 2013). "Stevens–Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN)". In Porter, R. S. (ed.). The Merck Manual ((online version) 19th ed.). Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co. Archived from the original on 3 May 2012.

- ↑ Auquier-Dunant A, Mockenhaupt M, Naldi L, Correia O, Schröder W, Roujeau JC; Mockenhaupt; Naldi; Correia; Schröder; Roujeau; SCAR Study Group. Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions (2002). "Correlations between clinical patterns and causes of Erythema Multiforme Majus, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis results of an international prospective study". Archives of Dermatology. 138 (8): 1019–24. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.8.1019. PMID 12164739.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Chong HY, Mohamed Z, Tan LL, Wu DB, Shabaruddin FH, Dahlui M, Apalasamy YD, Snyder SR, Williams MS, Hao J, Cavallari LH, Chaiyakunapruk N (2017). "Is universal HLA-B*15:02 screening a cost-effective option in an ethnically diverse population? A case study of Malaysia". The British Journal of Dermatology. 177 (4): 1102–1112. doi:10.1111/bjd.15498. PMC 5617756. PMID 28346659.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Su SC, Hung SI, Fan WL, Dao RL, Chung WH (2016). "Severe Cutaneous Adverse Reactions: The Pharmacogenomics from Research to Clinical Implementation". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 17 (11): 1890. doi:10.3390/ijms17111890. PMC 5133889. PMID 27854302.

- ↑ Ciralsky, JB; Sippel, KC; Gregory, DG (July 2013). "Current ophthalmologic treatment strategies for acute and chronic Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 24 (4): 321–8. doi:10.1097/icu.0b013e3283622718. PMID 23680755.

- ↑ Foster et al. 2013, Prognosis.

- ↑ Enerson, Ole Daniel (ed.), "Stevens-Johnson syndrome", Whonamedit?, archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ↑ Stevens, A.M.; Johnson, F.C. (1922). "A new eruptive fever associated with stomatitis and ophthalmia; Report of two cases in children". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 24 (6): 526–33. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1922.04120120077005. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014.

- ↑ Ramirez, Erika (8 August 2012). "Ab-Soul's timeline: The rapper's life from 5 years old to now". billboard.com. Billboard. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2012.

- ↑ Cartner-Morley, Jess (8 April 2006). "Beautiful and Damned". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Manute Bol dies at age 47". FanHouse. AOL. 19 June 2010. Archived from the original on 21 June 2010.

- ↑ Graff, Chad (31 July 2013). "3M golf: Gene Sauers thriving after torturous battle with skin disease". St. Paul Pioneer Press. Archived from the original on 3 October 2014.

- ↑ "Family awarded $63 million in Motrin case". Boston Globe. 13 February 2013. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017.

- ↑ "$63 million verdict in Children's Motrin case upheld". Boston Globe. 17 April 2015. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016.

- ↑ Morton, Karen. "Karen Morton Biography". imdb.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2016.

External links

- Bentley, John; Sie, David (8 October 2014). "Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis". The Pharmaceutical Journal. 293 (7832). Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- CS1: long volume value

- Use dmy dates from June 2012

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2018

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from November 2018

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2012

- Drug eruptions

- Rare syndromes

- RTT

- RTTEM