Influenza A virus subtype H5N1

| Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Insthoviricetes |

| Order: | Articulavirales |

| Family: | Orthomyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Alphainfluenzavirus |

| Species: | |

| Serotype: | Influenza A virus subtype H5N1

|

| Notable strains | |

Influenza A virus subtype H5N1 (A/H5N1) is a subtype of the influenza A virus which can cause illness in humans and many other animal species.[1] A bird-adapted strain of H5N1, called HPAI A(H5N1) for highly pathogenic avian influenza virus of type A of subtype H5N1, is the highly pathogenic causative agent of H5N1 flu, commonly known as avian influenza ("bird flu"). It is enzootic (maintained in the population) in many bird populations, especially in Southeast Asia. One strain of HPAI A(H5N1) is spreading globally after first appearing in Asia. It is epizootic (an epidemic in nonhumans) and panzootic (affecting animals of many species, especially over a wide area), killing tens of millions of birds and spurring the culling of hundreds of millions of others to stem its spread. Many references to "bird flu" and H5N1 in the popular media refer to this strain.[2]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, H5N1 pathogenicity is gradually continuing to rise in endemic areas, but the avian influenza disease situation in farmed birds is being held in check by vaccination, and there is "no evidence of sustained human-to-human transmission" of the virus.[3] Eleven outbreaks of H5N1 were reported worldwide in June 2008, in five countries (China, Egypt, Indonesia, Pakistan and Vietnam) compared to 65 outbreaks in June 2006, and 55 in June 2007. The global HPAI situation significantly improved in the first half of 2008, but the FAO reports that imperfect disease surveillance systems mean that occurrence of the virus remains underestimated and underreported.[4] As of May 2020, the WHO reported a total of 861 confirmed human cases which resulted in the deaths of 455 people since 2003.[5]

Several H5N1 vaccines have been developed and approved, and stockpiled by a number of countries, including the United States (in its National Stockpile),[6][7] Britain, France, Canada, and Australia, for use in an emergency.[8]

In April 2024, H5N1 had spread in dairy cows in many states of US, a worker in Texas also was infected and presented with conjunctivitis.[9] A highly contagious strain of H5N1, one that might allow airborne transmission between mammals, can be reached in only a few mutations, raising concerns about a pandemic and bioterrorism.[10]

Overview

|

| Influenza (Flu) |

|---|

|

HPAI A(H5N1) is considered an avian disease, although there is some evidence of limited human-to-human transmission of the virus.[11] A risk factor for contracting the virus is handling of infected poultry, but transmission of the virus from infected birds to humans has been characterized as inefficient.[12] Still, around 60% of humans known to have been infected with the Asian strain of HPAI A(H5N1) have died from it, and H5N1 may mutate or reassort into a strain capable of efficient human-to-human transmission. In 2003, world-renowned virologist Robert G. Webster published an article titled "The world is teetering on the edge of a pandemic that could kill a large fraction of the human population" in American Scientist. He called for adequate resources to fight what he sees as a major world threat to possibly billions of lives.[13] On September 29, 2005, David Nabarro, the newly appointed Senior United Nations System Coordinator for Avian and Human Influenza, warned the world that an outbreak of avian influenza could kill anywhere between 5 million and 150 million people.[14]

Due to the high lethality and virulence of HPAI A(H5N1), its endemic presence, its increasingly large host reservoir, and its significant ongoing mutations, in 2006, the H5N1 virus has been regarded to be the world's largest pandemic threat, and billions of dollars are being spent researching H5N1 and preparing for a potential influenza pandemic.[15] At least 12 companies and 17 governments are developing prepandemic influenza vaccines in 28 different clinical trials that, if successful, could turn a deadly pandemic infection into a nondeadly one. Full-scale production of a vaccine that could prevent any illness at all from the strain would require at least three months after the virus's emergence to begin, but it is hoped that vaccine production could increase until one billion doses were produced by one year after the initial identification of the virus.[16]

H5N1 may cause more than one influenza pandemic, as it is expected to continue mutating in birds regardless of whether humans develop herd immunity to a future pandemic strain.[17] Influenza pandemics from its genetic offspring may include influenza A virus subtypes other than H5N1.[18] While genetic analysis of the H5N1 virus shows that influenza pandemics from its genetic offspring can easily be far more lethal than the Spanish flu pandemic,[19] planning for a future influenza pandemic is based on what can be done and there is no higher Pandemic Severity Index level than a Category 5 pandemic which, roughly speaking, is any pandemic as bad as the Spanish flu or worse; and for which all intervention measures are to be used.[20]

Signs and symptoms

In general, humans who catch a humanized influenza A virus (a human flu virus of type A) usually have symptoms that include fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, conjunctivitis, and, in severe cases, breathing problems and pneumonia that may be fatal.[22] The severity of the infection depends in large part on the state of the infected persons' immune systems and whether they had been exposed to the strain before.[23][24]

The avian influenza hemagglutinin binds alpha 2-3 sialic acid receptors, while human influenza hemagglutinins bind alpha 2-6 sialic acid receptors.[25] This means when the H5N1 strain infects humans, it will replicate in the lower respiratory tract, and consequently will cause viral pneumonia.[26][27]

The reported mortality rate of highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza in a human is high; WHO data indicate 60% of cases classified as H5N1 resulted in death. However, there is some evidence the actual mortality rate of avian flu could be much lower, as there may be many people with milder symptoms who do not seek treatment and are not counted.[28][29]

In one case, a boy with H5N1 experienced diarrhea followed rapidly by a coma without developing respiratory or flu-like symptoms.[30] There have been studies of the levels of cytokines in humans infected by the H5N1 flu virus. Of particular concern is elevated levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, a protein associated with tissue destruction at sites of infection and increased production of other cytokines. Flu virus-induced increases in the level of cytokines is also associated with flu symptoms, including fever, chills, vomiting and headache. Tissue damage associated with pathogenic flu virus infection can ultimately result in death.[13] The inflammatory cascade triggered by H5N1 has been called a 'cytokine storm' by some, because of what seems to be a positive feedback process of damage to the body resulting from immune system stimulation. H5N1 induces higher levels of cytokines than the more common flu virus types.[31]

Birds

Signs of H5N1 in birds range from mild—decrease in egg production, nasal discharge, coughing and sneezing—to severe, including loss of coordination, energy, and appetite; soft-shelled or misshapen eggs; purple discoloration of the wattles, head, eyelids, combs, and hocks; and diarrhea. Sometimes the first noticeable sign is sudden death.[22]

Cause

Genetics

The first known strain of HPAI A(H5N1) (called A/chicken/Scotland/59) killed two flocks of chickens in Scotland in 1959, but that strain was very different from the highly pathogenic strain of H5N1. The dominant strain of HPAI A(H5N1) in 2004 evolved from 1999 to 2002 creating the Z genotype,[32] it has also been called "Asian lineage HPAI A(H5N1)".

Asian lineage HPAI A(H5N1) is divided into two antigenic clades. Clade 1 includes human and bird isolates from Vietnam, Thailand, and Cambodia and bird isolates from Laos and Malaysia. Clade 2 viruses were first identified in bird isolates from China, Indonesia, Japan, and South Korea before spreading westward.[33][34]

Genetic analysis has identified six subclades of clade 2, three of which have a distinct geographic distribution and have been implicated in human infections: Map[17][35][36]

- Subclade 1, Indonesia

- Subclade 2, Europe, Middle East, and Africa

- Subclade 3, China

A 2007 study focused on the EMA subclade has shed further light on the EMA mutations. "The 36 new isolates reported here greatly expand the amount of whole-genome sequence data available from recent avian influenza (H5N1) isolates. Before our project, GenBank contained only 5 other complete genomes from Europe for the 2004–2006 period, and it contained no whole genomes from the Middle East or northern Africa. Our analysis showed several new findings. First, all European, Middle Eastern, and African samples fall into a clade that is distinct from other contemporary Asian clades, all of which share common ancestry with the original 1997 Hong Kong strain. Phylogenetic trees built on each of the 8 segments show a consistent picture of 3 lineages, as illustrated by the HA tree shown in Figure 1. Two of the clades contain exclusively Vietnamese isolates; the smaller of these, with 5 isolates, we label V1; the larger clade, with 9 isolates, is V2. The remaining 22 isolates all fall into a third, clearly distinct clade, labeled EMA, which comprises samples from Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Trees for the other 7 segments display a similar topology, with clades V1, V2, and EMA clearly separated in each case. Analyses of all available complete influenza (H5N1) genomes and of 589 HA sequences placed the EMA clade as distinct from the major clades circulating in People's Republic of China, Indonesia, and Southeast Asia."[37]

Structure and subtypes

-

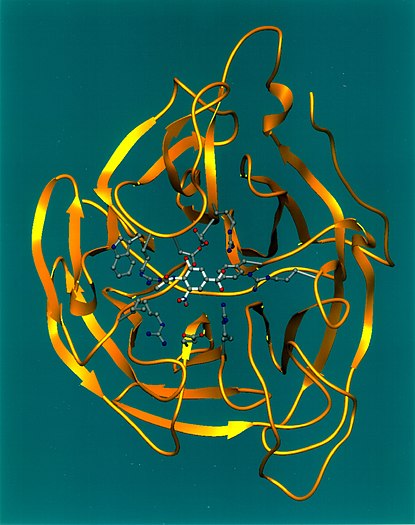

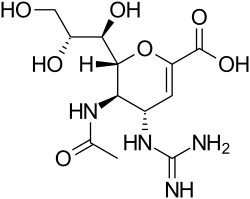

The H in H5N1 stands for "hemagglutinin", as depicted in this molecular model

-

The N in H5N1 stands for "Neuraminidase", the protein depicted in this ribbon diagram

H5N1 is a subtype of the species Influenza A virus of the genus Alphainfluenzavirus of the family Orthomyxoviridae. Like all other influenza A subtypes, the H5N1 subtype is an RNA virus. It has a segmented genome of eight negative sense, single-strands of RNA, abbreviated as PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, NA, MP and NS.[1][38]

HA codes for hemagglutinin, an antigenic glycoprotein found on the surface of the influenza viruses and is responsible for binding the virus to the cell that is being infected. NA codes for neuraminidase, an antigenic glycosylated enzyme found on the surface of the influenza viruses. It facilitates the release of progeny viruses from infected cells.[39] The hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) RNA strands specify the structure of proteins that are most medically relevant as targets for antiviral drugs and antibodies. HA and NA are also used as the basis for the naming of the different subtypes of influenza A viruses; this is where the H and N come from in H5N1.[40][41]

Influenza A virus subtypes that have been confirmed in humans, in order of the number of known human pandemic deaths that they have caused, include:

- H1N1 caused "Spanish flu" in 1918[42] and the 2009 swine flu pandemic[43]

- H2N2 caused "Asian flu" in the late 1950s[44]

- H3N2 caused "Hong Kong flu" in the late 1960s[45]

- H5N1, ("bird flu"), which is noted for having a strain (Asian-lineage HPAI H5N1) that kills over half the humans it infects.[1][46]

- H7N9 is responsible for a 2013 epidemic in China.[47]

- H7N7 has some zoonotic potential: it has rarely caused disease in humans[48][11]

- H1N2 is currently endemic in pigs and has rarely caused disease in humans[49]

- H9N2[50][51], H7N2[52] , H7N3[22], H5N2[53], H10N7[54] , H10N3[55][56], and H5N8[57]

Mutation rate

Influenza viruses have a relatively high mutation rate that is characteristic of RNA viruses. The segmentation of its genome facilitates genetic recombination by segment reassortment in hosts infected with two different strains of influenza viruses at the same time.[58][59]

The ability of various influenza strains to show species-selectivity is largely due to variation in the hemagglutinin genes. Genetic mutations in the hemagglutinin gene that cause single amino acid substitutions can significantly alter the ability of viral hemagglutinin proteins to bind to receptors on the surface of host cells. Such mutations in avian H5N1 viruses can change virus strains from being inefficient at infecting human cells to being as efficient in causing human infections as more common human influenza virus types.[60]

Influenza A virus subtype H3N2 is endemic in pigs in China, and has been detected in pigs in Vietnam, increasing fears of the emergence of new variant strains. The dominant strain of annual flu virus in January 2006 was H3N2, which is now resistant to the standard antiviral drugs amantadine and rimantadine. The possibility of H5N1 and H3N2 exchanging genes through reassortment is a major concern. If a reassortment in H5N1 occurs, it might remain an H5N1 subtype, or it could shift subtypes, as H2N2 did when it evolved into the Hong Kong Flu strain of H3N2.[61]

Both the H2N2 and H3N2 pandemic strains contained avian influenza virus RNA segments. "While the pandemic human influenza viruses of 1957 (H2N2) and 1968 (H3N2) clearly arose through reassortment between human and avian viruses, the influenza virus causing the 'Spanish flu' in 1918 appears to be entirely derived from an avian source".[62]

Transmission

Infected birds transmit H5N1 through their saliva, nasal secretions, feces and blood. Other animals may become infected with the virus through direct contact with these bodily fluids or through contact with surfaces contaminated with them. Low-pathogenic influenza viruses remains infectious after over 30 days at 0 C , or 4 days at 22 C; H5N1 at ordinary temperatures lasts in the environment for weeks. Because migratory birds are among the carriers of the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus, it is spreading to all parts of the world. H5N1 is different from all previously known highly pathogenic avian flu viruses in its ability to be spread by animals other than poultry. Waterfowl were revealed to be directly spreading this highly pathogenic strain to chickens, crows, pigeons, and other birds, and the virus was increasing its ability to infect mammals, as well. From this point on, avian flu experts increasingly referred to containment as a strategy that can delay, but not ultimately prevent, a future avian flu pandemic.[63][64][65][66]

Pathogenicity

H5N1 has mutated into a variety of strains with differing pathogenic profiles, some pathogenic to one species but not others, some pathogenic to multiple species. Each specific known genetic variation is traceable to a virus isolate of a specific case of infection. Through antigenic drift, H5N1 has mutated into dozens of highly pathogenic varieties divided into genetic clades which are known from specific isolates, but all belong to genotype Z of avian influenza virus H5N1, now the dominant genotype.[59][58] H5N1 isolates found in Hong Kong in 1997 and 2001 were not consistently transmitted efficiently among birds and did not cause significant disease in these animals. In 2002, new isolates of H5N1 were appearing within the bird population of Hong Kong. These new isolates caused acute disease, including severe neurological dysfunction and death in ducks. This was the first reported case of lethal influenza virus infection in wild aquatic birds since 1961.[67]

Genotype Z emerged in 2002 through reassortment from earlier highly pathogenic genotypes of H5N1[2] that first infected birds in China in 1996, and first infected humans in Hong Kong in 1997.[58][59][68] Genotype Z is endemic in birds in Southeast Asia, has created at least two clades that can infect humans, and is spreading across the globe in bird populations. Mutations occurring within this genotype are increasing their pathogenicity.[69]

Low pathogenic H5N1

Low pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 (LPAI H5N1) commonly occurs in wild birds. In most cases, it causes minor sickness or no noticeable signs of disease in birds. It is not known to affect humans at all.[70][71]

- 1966 – LPAI H5N1 A/Turkey/Ontario/6613/1966(H5N1) was detected in a flock of infected turkeys in Ontario, Canada[72][73]

- 1975 – LPAI H5N1 was detected in a wild mallard duck and a wild blue goose in Wisconsin.[74]

- 1981 and 1985 – LPAI H5N1 was detected in ducks by the University of Minnesota conducting a sampling procedure in which sentinel ducks were monitored in cages placed in the wild for a short period of time.[74]

- 1983 – LPAI H5N1 was detected in ring-billed gulls in Pennsylvania.[74]

- 1986 – LPAI H5N1 was detected in a wild mallard duck in Ohio.[74]

- 2005 – LPAI H5N1 was detected in ducks in Manitoba, Canada.[74]

- 2009 – LPAI H5N1 was detected in commercial poultry in British Columbia.[75]

"In the past, there was no requirement for reporting or tracking LPAI H5 or H7 detections in wild birds so states and universities tested wild bird samples independently of USDA. Because of this, the above list of previous detections might not be all inclusive of past LPAI H5N1 detections. However, the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) recently changed its requirement of reporting detections of avian influenza. Effective in 2006, all confirmed LPAI H5 and H7 AI subtypes must be reported to the OIE because of their potential to mutate into highly pathogenic strains. Therefore, USDA now tracks these detections in wild birds, backyard flocks, commercial flocks and live bird markets."[76]

Diagnosis

In terms of a definite diagnosis for H5N1, cell culture or direct fluorescent antibody assay may be used; PCR is also available for this purpose[77][78]

Prevention

Vaccine

In January 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved an adjuvanted influenza A (H5N1) monovalent vaccine.[79][80]

While vaccines can sometimes provide cross-protection against related flu strains, the best protection would be from a vaccine specifically produced for any future pandemic flu virus strain. Daniel R. Lucey, co-director of the Biohazardous Threats and Emerging Diseases graduate program at Georgetown University has made this point, "There is no H5N1 pandemic so there can be no pandemic vaccine".[81] However, "pre-pandemic vaccines" have been created; are being refined and tested; and do have some promise both in furthering research and preparedness for the next pandemic.[82][83][84]

Public health

"The United States is collaborating closely with eight international organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), and 88 foreign governments to address the situation through planning, greater monitoring, and full transparency in reporting and investigating avian influenza occurrences. The United States and these international partners have led global efforts to encourage countries to heighten surveillance for outbreaks in poultry and significant numbers of deaths in migratory birds and to rapidly introduce containment measures. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and Agriculture (USDA) are coordinating future international response measures on behalf of the White House with departments and agencies across the federal government".[85]

Together steps are being taken to "minimize the risk of further spread in animal populations", "reduce the risk of human infections", and "further support pandemic planning and preparedness".[85]

Ongoing detailed mutually coordinated onsite surveillance and analysis of human and animal H5N1 avian flu outbreaks are being conducted and reported by the USGS National Wildlife Health Center, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, the European Commission, and others.[86]

Treatment

There is no highly effective treatment for H5N1 flu, but oseltamivir (commercially marketed by Roche as Tamiflu), can sometimes inhibit the influenza virus from spreading inside the user's body. This drug has become a focus for some governments and organizations trying to prepare for a possible H5N1 pandemic.[87] On April 20, 2006, Roche AG announced that a stockpile of three million treatment courses of Tamiflu are waiting at the disposal of the World Health Organization to be used in case of a flu pandemic; separately Roche donated two million courses to the WHO for use in developing nations that may be affected by such a pandemic but lack the ability to purchase large quantities of the drug.[88]

However, WHO expert Hassan al-Bushra has said:

- "Even now, we remain unsure about Tamiflu's real effectiveness. As for a vaccine, work cannot start on it until the emergence of a new virus, and we predict it would take six to nine months to develop it. For the moment, we cannot by any means count on a potential vaccine to prevent the spread of a contagious influenza virus, whose various precedents in the past 90 years have been highly pathogenic".[89]

Prognosis

In terms of individuals that need hospitalization for H5N1 subtype infection, mortality is 60 percent, hence prognosis in hospitalized individuals is rather poor.[90]

Epidemiology

The earliest infections of humans by H5N1 coincided with an epizootic (an epidemic in nonhumans) of H5N1 influenza in Hong Kong's poultry population in 1997. This panzootic (a disease affecting animals of many species, especially over a wide area) outbreak was stopped by the killing of the entire domestic poultry population within the territory. However, the disease has continued to spread; outbreaks were reported in Asia again in 2003. On December 21, 2009 the WHO announced a total of 447 cases which resulted in the deaths of 263.[22][91]

H5N1 is easily transmissible between birds, facilitating a potential global spread of H5N1. While H5N1 undergoes mutation and reassortment, creating variations which can infect species not previously known to carry the virus, not all of these variant forms can infect humans. H5N1 as an avian virus preferentially binds to a type of galactose receptors that populate the avian respiratory tract from the nose to the lungs and are virtually absent in humans, occurring only in and around the alveoli, structures deep in the lungs where oxygen is passed to the blood. Therefore, the virus is not easily expelled by coughing and sneezing, the usual route of transmission.[25][26][92]

H5N1 is mainly spread by domestic poultry, both through the movements of infected birds and poultry products and through the use of infected poultry manure as fertilizer or feed. Humans with H5N1 have typically caught it from chickens, which were in turn infected by other poultry or waterfowl. Migrating waterfowl (wild ducks, geese and swans) carry H5N1, often without becoming sick.[63][93] Many species of birds and mammals can be infected with HPAI A(H5N1), but the role of animals other than poultry and waterfowl as disease-spreading hosts is unknown.[94]

According to a report by the World Health Organization, H5N1 may be spread indirectly. The report stated the virus may sometimes stick to surfaces or get kicked up in fertilizer dust to infect people.[95]

Host range

"Since 1997, studies of influenza A (H5N1) indicate that these viruses continue to evolve, with changes in antigenicity and internal gene constellations; an expanded host range in avian species and the ability to infect felids; enhanced pathogenicity in experimentally infected mice and ferrets, in which they cause systemic infections; and increased environmental stability."[96]

The New York Times, in an article on transmission of H5N1 through smuggled birds, reports Wade Hagemeijer of Wetlands International stating, "We believe it is spread by both bird migration and trade, but that trade, particularly illegal trade, is more important".[97]

On September 29, 2007, researchers reported the H5N1 bird flu virus can also pass through a pregnant woman's placenta to infect the fetus. They also found evidence of what doctors had long suspected—the virus not only affects the lungs, but also passes throughout the body into the gastrointestinal tract, the brain, liver, and blood cells.[98]

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | Total | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 5 | 62.5% | 8 | 5 | 62.5% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 0 | 0% | 3 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 8 | 1 | 12.5% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 4 | 100% | 2 | 2 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 8 | 8 | 100% | 3 | 3 | 100% | 26 | 14 | 53.8% | 9 | 4 | 44.4% | 6 | 4 | 66.7% | 5 | 1 | 20.0% | 67 | 42 | 62.7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1[99] | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 100% | 8 | 5 | 62.5% | 13 | 8 | 61.5% | 5 | 3 | 60.0% | 4 | 4 | 100% | 7 | 4 | 57.1% | 2 | 1 | 50.0% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 2 | 1 | 50.0% | 2 | 2 | 100% | 2 | 0 | 0% | 6 | 1 | 16.7% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 55 | 32 | 58.2% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | 10 | 55.6% | 25 | 9 | 36.0% | 8 | 4 | 50.0% | 39 | 4 | 10.3% | 29 | 13 | 44.8% | 39 | 15 | 38.5% | 11 | 5 | 45.5% | 4 | 3 | 75.0% | 37 | 14 | 37.8% | 136 | 39 | 28.7% | 10 | 3 | 30.0% | 3 | 1 | 33.3% | 359 | 120 | 33.4% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 13 | 65.0% | 55 | 45 | 81.8% | 42 | 37 | 88.1% | 24 | 20 | 83.3% | 21 | 19 | 90.5% | 9 | 7 | 77.8% | 12 | 10 | 83.3% | 9 | 9 | 100% | 3 | 3 | 100% | 2 | 2 | 100% | 2 | 2 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 200 | 168 | 84.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 2 | 66.6% | 3 | 2 | 66.6% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 3 | 2 | 66.7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 1 | 100% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 1 | 33.3% | 3 | 1 | 33.3% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 0 | 0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | 12 | 70.6% | 5 | 2 | 40.0% | 3 | 3 | 100% | 25 | 17 | 68.0% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 4 | 33.3% | 12 | 4 | 33.3% | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 4 | 0 | 0% | 5 | 0 | 0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 0 | 0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 3 | 100% | 29 | 20 | 69.0% | 61 | 19 | 31.1% | 8 | 5 | 62.5% | 6 | 5 | 83.3% | 5 | 5 | 100% | 7 | 2 | 28.6% | 4 | 2 | 50.0% | 2 | 1 | 50.0% | 2 | 2 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 129 | 65 | 50.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 4 | 100% | 46 | 32 | 69.6% | 98 | 43 | 43.9% | 115 | 79 | 68.7% | 88 | 59 | 67.0% | 44 | 33 | 75.0% | 73 | 32 | 43.8% | 48 | 24 | 50.0% | 62 | 34 | 54.8% | 32 | 20 | 62.5% | 39 | 25 | 64.1% | 52 | 22 | 42.3% | 145 | 42 | 29.0% | 10 | 3 | 30.0% | 4 | 2 | 50.0% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1 | 0 | 0% | 2 | 1 | 50.0% | 6 | 1 | 16.7% | 12 | 4 | 33.3% | 7 | 2 | 28.6% | 889 | 463 | 52.1% |

In May 2013, North Korea confirmed a H5N1 bird flu outbreak that forced authorities to kill over 160,000 ducks in Pyongyang.[100]

Terminology

H5N1 isolates are identified like this actual HPAI A(H5N1) example, A/chicken/Nakorn-Patom/Thailand/CU-K2/04(H5N1):[101][102]

- A stands for the genus of influenza (A, B or C).

- chicken is the animal species the isolate was found in (note: human isolates lack this component term and are thus identified as human isolates by default)

- Nakorn-Patom/Thailand is the place this specific virus was isolated

- CU-K2 is the laboratory reference number that identifies it from other influenza viruses isolated at the same place and year

- 04 represents the year of isolation 2004

- H5 stands for the fifth of several known types of the protein hemagglutinin.

- N1 stands for the first of several known types of the protein neuraminidase.

Other examples include: A/duck/Hong Kong/308/78(H5N3), A/avian/NY/01(H5N2), A/chicken/Mexico/31381-3/94(H5N2), and A/shoveler/Egypt/03(H5N2).[103] As with other avian flu viruses, H5N1 has strains called "highly pathogenic" (HP) and "low-pathogenic" (LP). Avian influenza viruses that cause HPAI are highly virulent, and mortality rates in infected flocks often approach 100%. LPAI viruses have negligible virulence, but these viruses can serve as progenitors to HPAI viruses. The strain of H5N1 responsible for the deaths of birds across the world is an HPAI strain; all other strains of H5N1, including a North American strain that causes no disease at all in any species, are LPAI strains. All HPAI strains identified to date have involved H5 and H7 subtypes. The distinction concerns pathogenicity in poultry, not humans. Normally, a highly pathogenic avian virus is not highly pathogenic to either humans or nonpoultry birds. This deadly strain of H5N1 is unusual in being deadly to so many species, including some, like domestic cats, never previously susceptible to any influenza virus.[104]

Research

Animal and lab studies suggest that Relenza (zanamivir), which is in the same class of drugs as Tamiflu, may also be effective against H5N1. In a study performed on mice in 2000, "zanamivir was shown to be efficacious in treating avian influenza viruses H9N2, H6N1, and H5N1 transmissible to mammals".[105] In addition, mice studies suggest the combination of zanamivir, celecoxib and mesalazine looks promising producing a 50% survival rate compared to no survival in the placebo arm.[106] While no one knows if zanamivir will be useful or not on a yet to exist pandemic strain of H5N1, it might be useful to stockpile zanamivir as well as oseltamivir in the event of an H5N1 influenza pandemic. Neither oseltamivir nor zanamivir can be manufactured in quantities that would be meaningful once efficient human transmission starts.[107] In September, 2006, a WHO scientist announced that studies had confirmed cases of H5N1 strains resistant to Tamiflu and Amantadine.[108] Tamiflu-resistant strains have also appeared in the EU, which remain sensitive to Relenza.[109][110]

Novel, contagious strains of H5N1 were created by Ron Fouchier of the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, who first presented his work to the public at an influenza conference in Malta in September 2011. Three mutations were introduced into the H5N1 virus genome, and the virus was then passed from the noses of infected ferrets to the noses of uninfected ones, which was repeated 10 times;[111] after these 10 passages the H5N1 virus had acquired the ability of transmission between ferrets via aerosols or respiratory droplets.

After Fouchier offered an article describing this work to the leading academic journal Science, the US National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB) recommended against publication of the full details of the study, and the one submitted to Nature by Yoshihiro Kawaoka of the University of Wisconsin describing related work. However, after additional consultations at the World Health Organization and by the NSABB, the NSABB reversed its position and recommended publication of revised versions of the two papers.[112] However, then the Dutch government declared that this type of manuscripts required Fouchier to apply for an export permit in the light of EU directive 428/2009 on dual use goods.[note 1] After much controversy surrounding the publishing of his research, Fouchier complied (under formal protest) with Dutch government demands to obtain a special permit[113] for submitting his manuscript, and his research appeared in a special issue of the journal Science devoted to H5N1.[114][115][116] The papers by Fouchier and Kawaoka conclude that it is entirely possible that a natural chain of mutations could lead to an H5N1 virus acquiring the capability of airborne transmission between mammals, and that a H5N1 influenza pandemic would not be impossible.[117]

In May 2013, it was reported that scientists at the Harbin Veterinary Research Institute in Harbin, China had created H5N1 strains which passed between guinea pigs.[118]

In response to Fouchier and Kawaoka's work, a number of scientists expressed concerns with the risks of creating novel potential pandemic pathogens, culminating in the formation of The Cambridge Working Group, a Consensus Statement calling for an assessment of the risks and benefits of such research.[119][120]

Society and culture

H5N1 has had a significant effect on human society, especially the financial, political, social, and personal responses to both actual and predicted deaths in birds, humans, and other animals. Billions of U.S. dollars are being raised and spent to research H5N1 and prepare for a potential avian influenza pandemic. Over $10 billion have been spent and over 200 million birds have been killed to try to contain H5N1.[15][121][122][123]

People have reacted by buying less chicken, causing poultry sales and prices to fall.[124] Many individuals have stockpiled supplies for a possible flu pandemic. International health officials and other experts have pointed out that many unknown questions still hover around the disease.[125]

Dr. David Nabarro, Chief Avian Flu Coordinator for the United Nations, and former Chief of Crisis Response for the World Health Organization has described himself as "quite scared" about H5N1's potential impact on humans. Nabarro has been accused of being alarmist before, and on his first day in his role for the United Nations, he proclaimed the avian flu could kill 150 million people. In an interview with the International Herald Tribune, Nabarro compares avian flu to AIDS in Africa, warning that underestimations led to inappropriate focus for research and intervention.[126]

In February 2020 an outbreak of H5N1 avian flu occurred in Shuangqing District of Shaoyang City, in the Hunan province. After poultry had become ill from the virus the city killed close to 18,000 chickens to prevent the spread of the illness. Hunan borders Hubei province where Wuhan is located, the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic.[127]

See also

- Antigenic shift

- Avian influenza virus

- Favipiravir

- Fujian flu

- H5N1 clinical trials

- H7N9

- Influenza research

- Influenzavirus A

- International Conference on Emerging Infectious Diseases

- National Influenza Centers

- Swine influenza

- Zoonosis

Notes

- ↑ The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) lists strategic goods with prohibited goods or goods that require a special permit for import and export without which the carrier faces pecuniary punishment or up to 5 years' imprisonment.

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2002). "46.0.1. Influenzavirus A". Archived from the original on 2004-12-07. Retrieved 2006-04-17.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Li KS, Guan Y, Wang J, Smith GJ, Xu KM, Duan L, Rahardjo AP, Puthavathana P, Buranathai C, Nguyen TD, Estoepangestie AT, Chaisingh A, Auewarakul P, Long HT, Hanh NT, Webby RJ, Poon LL, Chen H, Shortridge KF, Yuen KY, Webster RG, Peiris JS (2004). "Genesis of a highly pathogenic and potentially pandemic H5N1 influenza virus in eastern Asia". Nature. 430 (6996): 209–213. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..209L. doi:10.1038/nature02746. PMID 15241415. S2CID 4410379.

This was reprinted in 2005: Li KS, Guan Y, Wang J, Smith GJ, Xu KM, Duan L, Rahardjo AP, Puthavathana P, Buranathai C, Nguyen TD, Estoepangestie AT, Chaisingh A, Auewarakul P, Long HT, Hanh NT, Webby RJ, Poon LL, Chen H, Shortridge KF, Yuen KY, Webster RG, Peiris JS (2005). "Today's Pandemic Threat: Genesis of a Highly Pathogenic and Potentially Pandemic H5N1 Influenza Virus in Eastern Asia". In Knobler SL, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon SM (eds.). The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary (2005). Washington DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 116–130. Archived from the original on 2006-09-14. - ↑ Situation updates – Avian influenza Archived 2013-08-19 at the Wayback Machine. World Health Organization.

- ↑ "October 11, 2010 FAO Avian Influenza Disease Emergency Situation Update 70" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 30, 2011. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ↑ "Cumulative number of confirmed human cases for avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO, 2003-2020" (PDF). World Health Organization. World Health Organization. 2020-05-08. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-06-03. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- ↑ H5N1 Influenza Virus Vaccine, manufactured by Sanofi Pasteur, Inc. Questions and Answers Archived 2013-08-15 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- ↑ Availability of a new recombinant H5N1 vaccine virus Archived 2014-01-06 at the Wayback Machine, June 2010, World Health Organization; Availability of a new recombinant H5N1 vaccine virus Archived 2014-01-06 at the Wayback Machine, May 2009, World Health Organization.

- ↑ UK to buy bird flu vaccine stock Archived 2014-01-06 at the Wayback Machine, BBC, February 4, 2009.

- ↑ "MSN". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on 5 April 2024. Retrieved 3 April 2024.

- ↑ "Fears of bioterrorism or an accidental release". 16 February 2012. Archived from the original on 21 November 2012.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ungchusak K, Auewarakul P, Dowell SF, et al. (January 2005). "Probable person-to-person transmission of avian influenza A (H5N1)". N Engl J Med. 352 (4): 333–340. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044021. PMID 15668219. S2CID 10729294.

- ↑ Ortiz JR, Katz MA, Mahmoud MN, et al. (December 2007). "Lack of evidence of avian-to-human transmission of avian influenza A (H5N1) virus among poultry workers, Kano, Nigeria, 2006". J Infect Dis. 196 (11): 1685–1691. doi:10.1086/522158. PMID 18008254.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Webster, R. G. and Walker, E. J. (2003). "The world is teetering on the edge of a pandemic that could kill a large fraction of the human population". American Scientist. 91 (2): 122. doi:10.1511/2003.2.122. Archived from the original on 2014-03-08.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ United Nations (2005-09-29). "Press Conference by UN System Senior Coordinator for Avian, Human Influenza". UN News and Media Division, Department of Public Information, New York. Archived from the original on 2006-04-20. Retrieved 2006-04-17.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Rosenthal E, Bradsher K (2006-03-16). "Is Business Ready for a Flu Pandemic?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ↑ Science and Development Network Archived 2012-07-16 at the Wayback Machine article Pandemic flu: fighting an enemy that is yet to exist published May 3, 2006.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Robert G. Webster; Elena A. Govorkova, M.D. (November 23, 2006). "H5N1 Influenza – Continuing Evolution and Spread". NEJM. 355 (21): 2174–2177. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068205. PMID 17124014.

- ↑ CDC Archived 2009-10-06 at the Wayback Machine Article 1918 Influenza: the Mother of All Pandemics by Jeffery K. Taubenberger published January 2006

- ↑ Christophersen, Olav Albert; Haug, Anna (11 July 2006). "Why is the world so poorly prepared for a pandemic of hypervirulent avian influenza?". Microbial Ecology in Health and Disease. 18 (3–4): 113–132. doi:10.1080/08910600600866544. S2CID 218565955.

- ↑ Roos, Robert; Lisa Schnirring (February 1, 2007). "HHS ties pandemic mitigation advice to severity". University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP). Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- ↑ Korteweg C, Gu J (May 2008). "Pathology, Molecular Biology, and Pathogenesis of Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Infection in Humans". Am. J. Pathol. 172 (5): 1155–1170. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2008.070791. PMC 2329826. PMID 18403604.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 "NIOSH alert: protecting poultry workers from avian influenza (bird flu)". CDC. 7 July 2020. doi:10.26616/NIOSHPUB2008128. Archived from the original on 10 January 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ↑ Peiris, Joseph Sriyal Malik; Cheung, Chung Yan; Leung, Connie Yin Hung; Nicholls, John Malcolm (December 2009). "Innate immune responses to influenza A H5N1: friend or foe?". Trends in Immunology. 30 (12): 574–584. doi:10.1016/j.it.2009.09.004. PMC 5068224. PMID 19864182.

- ↑ Rimmelzwaan, Guus F.; Katz, Jacqueline M. (December 2013). "Immune responses to infection with H5N1 influenza virus". Virus Research. 178 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1016/j.virusres.2013.05.011. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Shinya K, Ebina M, Yamada S, Ono M, Kasai N, Kawaoka Y (March 2006). "Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway". Nature. 440 (7083): 435–436. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..435S. doi:10.1038/440435a. PMID 16554799. S2CID 9472264.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 van Riel D, Munster VJ, de Wit E, Rimmelzwaan GF, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Kuiken T (2006). "H5N1 Virus Attachment to Lower Respiratory Tract". Science. 312 (5772): 399. doi:10.1126/science.1125548. PMID 16556800.

- ↑ Lye, DC; Ang, BS; Leo, YS (April 2007). "Review of human infections with avian influenza H5N1 and proposed local clinical management guideline". Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 36 (4): 285–92. ISSN 0304-4602. PMID 17483860. Archived from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

- ↑ Leslie Taylor (2006). "Overestimating Avian Flu". Seed Magazine. Archived from the original on 2008-02-20. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Anna Thorson, MD; Max Petzold; Nguyen Thi Kim Chuc; Karl Ekdahl, MD (2006). "Is Exposure to Sick or Dead Poultry Associated With Flulike Illness?". Arch Intern Med. 166 (1): 119–123. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.1.119. PMID 16401820.

- ↑ de Jong MD, Bach VC, Phan TQ, Vo MH, Tran TT, Nguyen BH, Beld M, Le TP, Truong HK, Nguyen VV, Tran TH, Do QH, Farrar J (2005). "Fatal avian influenza A (H5N1) in a child presenting with diarrhea followed by coma". N. Engl. J. Med. 352 (7): 686–691. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044307. PMID 15716562. S2CID 17703507.

- ↑ Chan MC, Cheung CY, Chui WH, Tsao SW, Nicholls JM, Chan YO, Chan RW, Long HT, Poon LL, Guan Y, Peiris JS (2005). "Proinflammatory cytokine responses induced by influenza A (H5N1) viruses in primary human alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells". Respir. Res. 6 (1): 135. doi:10.1186/1465-9921-6-135. PMC 1318487. PMID 16283933.

- ↑ Harder, T. C.; Werner, O. (2006). "Avian Influenza". In Kamps, B. S.; Hoffman, C.; Preiser, W. (eds.). Influenza Report 2006. Paris: Flying Publisher. ISBN 978-3-924774-51-6. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016.

- ↑ Koel, Björn F.; van der Vliet, Stefan; Burke, David F.; Bestebroer, Theo M.; Bharoto, Eny E.; Yasa, I. Wayan W.; Herliana, Inna; Laksono, Brigitta M.; Xu, Kemin; Skepner, Eugene; Russell, Colin A.; Rimmelzwaan, Guus F.; Perez, Daniel R.; Osterhaus, Albert D. M. E.; Smith, Derek J.; Prajitno, Teguh Y.; Fouchier, Ron A. M. (July 2014). "Antigenic Variation of Clade 2.1 H5N1 Virus Is Determined by a Few Amino Acid Substitutions Immediately Adjacent to the Receptor Binding Site". mBio. 5 (3): e01070–14. doi:10.1128/mBio.01070-14. PMC 4056550. PMID 24917596.

- ↑ "Evolution of H5N1 Avian Influenza Viruses in Asia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (10): 1515–1526. October 2005. doi:10.3201/eid1110.050644. Archived from the original on 11 May 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "WHO changes H5N1 strains for pandemic vaccines, raising concern over virus evolution". Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP). August 18, 2006. Archived from the original on February 5, 2012.

- ↑ "Antigenic and genetic characteristics of H5N1 viruses and candidate H5N1 vaccine viruses developed for potential use as pre-pandemic vaccines" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). August 18, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2006.

- ↑ CDC Archived 2012-12-28 at the Wayback Machine article Genome Analysis Linking Recent European and African Influenza (H5N1) Viruses EID Journal Home > Volume 13, Number 5–May 2007 Volume 13, Number 5–May 2007

- ↑ Russell, Rupert J.; Haire, Lesley F.; Stevens, David J.; Collins, Patrick J.; Lin, Yi Pu; Blackburn, G. Michael; Hay, Alan J.; Gamblin, Steven J.; Skehel, John J. (7 September 2006). "The structure of H5N1 avian influenza neuraminidase suggests new opportunities for drug design". Nature. 443 (7107): 45–49. Bibcode:2006Natur.443...45R. doi:10.1038/nature05114. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 16915235. S2CID 4302838. Archived from the original on 25 March 2022. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ↑ Couch, R. (1996). "Chapter 58. Orthomyxoviruses Multiplication". In Baron, S. (ed.). Medical Microbiology. Galveston: The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. ISBN 978-0-9631172-1-2. Archived from the original on May 3, 2009.

- ↑ Li, F.; Ma, C.; Wang, J. (2015). "Inhibitors targeting the influenza virus hemagglutinin". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 22 (11): 1361–1382. doi:10.2174/0929867322666150227153919. ISSN 1875-533X. PMID 25723505. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ↑ "Types of Influenza Viruses". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 November 2021. Archived from the original on 21 January 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ "1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus) | Pandemic Influenza (Flu) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Jilani, Talha N.; Jamil, Radia T.; Siddiqui, Abdul H. (2022). "H1N1 Influenza". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ "1957-1958 Pandemic (H2N2 virus) | Pandemic Influenza (Flu) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 January 2019. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Tam, John S. (15 May 2002). "Influenza A (H5N1) in Hong Kong: an overview". Vaccine. 20 Suppl 2: S77–81. doi:10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00137-8. ISSN 0264-410X. PMID 12110265. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ↑ Yamamoto, Yu; Nakamura, Kikuyasu; Mase, Masaji (15 August 2017). "Survival of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus in Tissues Derived from Experimentally Infected Chickens". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 83 (16): e00604–17. doi:10.1128/AEM.00604-17. ISSN 1098-5336. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "New bird flu strain in China "one of the most lethal" warns WHO". MercoPress. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- ↑ Boston, 677 Huntington Avenue; Ma 02115 +1495‑1000 (2013-10-24). "Making the leap". News. Archived from the original on 3 January 2021. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- ↑ Komadina N, McVernon J, Hall R, Leder K (2014). "A historical perspective of influenza A(H1N2) virus". Emerg Infect Dis. 20 (1): 6–12. doi:10.3201/eid2001.121848. PMC 3884707. PMID 24377419.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Guan Y, Shortridge KF, Krauss S, Webster RG (August 1999). "Molecular characterization of H9N2 influenza viruses: were they the donors of the "internal" genes of H5N1 viruses in Hong Kong?". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (16): 9363–7. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.9363G. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.16.9363. PMC 17788. PMID 10430948.

- ↑ NAID NIH Archived 2010-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "CDC: Influenza Type A Viruses". Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ↑ [1] Archived 6 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine article Kuwait: Avian influenza H5N1 confirmed case in flamingo November 12, 2005

- ↑ Wright PF, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y (2013). "41-Orthomyxoviruses". In Knipe DM, Howley PM (eds.). Fields Virology. Vol. 1 (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 1201. ISBN 978-1-4511-0563-6.

- ↑ Patton, Dominique; Gu, Hallie (1 June 2021). "China reports first human case of H10N3 bird flu". www.reuters.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ↑ Wang, Yang; Niu, Shaowei; Zhang, Bing; Yang, Chenghuai; Zhou, Zhonghui (27 June 2021). "The whole genome analysis for the first human infection with H10N3 influenza virus in China". The Journal of Infection. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2021.06.021. ISSN 1532-2742. PMID 34192524. S2CID 235696703.

- ↑ "Human infection with avian influenza A (H5N8) – the Russian Federation". World Health Organization. 26 February 2021. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 Kou Z, Lei FM, Yu J, Fan ZJ, Yin ZH, Jia CX, Xiong KJ, Sun YH, Zhang XW, Wu XM, Gao XB, Li TX (2005). "New Genotype of Avian Influenza H5N1 Viruses Isolated from Tree Sparrows in China". J. Virol. 79 (24): 15460–15466. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.24.15460-15466.2005. PMC 1316012. PMID 16306617.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 The World Health Organization Global Influenza Program Surveillance Network. (2005). "Evolution of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in Asia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (10): 1515–1521. doi:10.3201/eid1110.050644. PMC 3366754. PMID 16318689.

Figure 1 shows a diagramatic representation of the genetic relatedness of Asian H5N1 hemagglutinin genes from various isolates of the virus - ↑ Gambaryan A, Tuzikov A, Pazynina G, Bovin N, Balish A, Klimov A (2006). "Fatal Evolution of the receptor binding phenotype of influenza A (H5) viruses". Virology. 344 (2): 432–438. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2005.08.035. PMID 16226289.

- ↑ Ayora-Talavera, Guadalupe; Shelton, Holly; Scull, Margaret A.; Ren, Junyuan; Jones, Ian M.; Pickles, Raymond J.; Barclay, Wendy S. (18 November 2009). "Mutations in H5N1 influenza virus hemagglutinin that confer binding to human tracheal airway epithelium". PLOS ONE. 4 (11): e7836. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7836A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007836. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2775162. PMID 19924306."However, laboratory-generated recombinant viruses have shown that surface antigen genes from South East Asian H5N1 viruses are compatible with internal viral genes from currently circulating H3N2 human strains and coinfection of ferret in a laboratory setting produced in vivo reassortants with mixtures of genes derived from human circulating virus and H5N1"

- ↑ Harder, T. C.; Werner, O. (2006). "Avian Influenza". In Kamps, B. S.; Hoffman, C.; Preiser, W. (eds.). Influenza Report 2006. Paris: Flying Publisher. ISBN 978-3-924774-51-6. Archived from the original on May 10, 2016.

This e-book is under constant revision and is an excellent guide to Avian Influenza - ↑ 63.0 63.1 "Wild birds and Avian Influenza". 1 November 2006. Archived from the original on 2006-11-01. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ↑ Jong, De; D, Menno (October 2008). "H5N1 Transmission and Disease: Observations from the Frontlines". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 27 (10): S54-6. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3181684d2d. ISSN 0891-3668. PMID 18820578. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ↑ Henning, Joerg; Wibawa, Hendra; Morton, John; Usman, Tri Bhakti; Junaidi, Akhmad; Meers, Joanne (August 2010). "Scavenging Ducks and Transmission of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, Java, Indonesia". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 16 (8): 1244–1250. doi:10.3201/eid1608.091540. PMC 3298304. PMID 20678318.

- ↑ Khalenkov, Alexey; Laver, W. Graeme; Webster, Robert G. (April 2008). "Detection and isolation of H5N1 influenza virus from large volumes of natural water". Journal of Virological Methods. 149 (1): 180–183. doi:10.1016/j.jviromet.2008.01.001. Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ↑ Sturm-Ramirez KM, Ellis T, Bousfield B, Bissett L, Dyrting K, Rehg JE, Poon L, Guan Y, Peiris M, Webster RG (2004). "Reemerging H5N1 Influenza Viruses in Hong Kong in 2002 Are Highly Pathogenic to Ducks". J. Virol. 78 (9): 4892–45901. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.9.4892-4901.2004. PMC 387679. PMID 15078970.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2005-10-28). "H5N1 avian influenza: timeline" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ Chen H, Deng G, Li Z, Tian G, Li Y, Jiao P, Zhang L, Liu Z, Webster RG, Yu K (2004). "The evolution of H5N1 influenza viruses in ducks in southern China". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (28): 10452–10457. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10110452C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403212101. PMC 478602. PMID 15235128.

- ↑ "H5N1 Bird Flu Poses Low Risk to the Public". www.cdc.gov. 25 March 2022. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2022.

- ↑ Kim, B.-S.; Kang, H.-M.; Choi, J.-G.; Kim, M.-C.; Kim, H.-R.; Paek, M.-R.; Kwon, J.-H.; Lee, Y.-J. (July 2011). "Characterization of the low-pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus in South Korea". Poultry Science. 90 (7): 1449–1461. Archived from the original on 27 May 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ Lang G.; Rouse B. T.; Narayan O.; Ferguson A. E.; Connell M. C. (1968). "A new influenza virus infection in turkeys. I. Isolation and characterization of virus 6213". Can Vet J. 9 (1): 22–29. PMC 1697084. PMID 17421891.

- ↑ Ping Jihui; Selman Mohammed; Tyler Shaun; Forbes Nicole; Keleta Liya; Brown Earl G (2012). "Low-pathogenic avian influenza virus A/turkey/Ontario/6213/1966 (H5N1) is the progenitor of highly pathogenic A/turkey/Ontario/7732/1966 (H5N9)". J Gen Virol. 93 (Pt 8): 1649–1657. doi:10.1099/vir.0.042895-0. PMC 3541759. PMID 22592261.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 "USDA AVIAN INFLUENZA FACT SHEET" (PDF). USDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ↑ "Avian Influenza Detected In British Columbia". Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). January 24, 2009. Archived from the original on January 31, 2009.

- ↑ "Avian Influenza Low Pathogenic H5N1 vs. Highly Pathogenic H5N1 – Latest Update". United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). August 17, 2006. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010.

- ↑ Shinya, Kyoko; Hatta, Masato; Yamada, Shinya; Takada, Ayato; Watanabe, Shinji; Halfmann, Peter; Horimoto, Taisuke; Neumann, Gabriele; Kim, Jin Hyun; Lim, Wilina; Guan, Yi; Peiris, Malik; Kiso, Makoto; Suzuki, Takashi; Suzuki, Yasuo; Kawaoka, Yoshihiro (August 2005). "Characterization of a Human H5N1 Influenza A Virus Isolated in 2003". Journal of Virology. 79 (15): 9926–9932. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.15.9926-9932.2005. PMC 1181571. PMID 16014953.

- ↑ Habib-Bein, Nadia F.; Beckwith, William H.; Mayo, Donald; Landry, Marie L. (August 2003). "Comparison of SmartCycler Real-Time Reverse Transcription-PCR Assay in a Public Health Laboratory with Direct Immunofluorescence and Cell Culture Assays in a Medical Center for Detection of Influenza A Virus". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 41 (8): 3597–3601. doi:10.1128/JCM.41.8.3597-3601.2003. PMC 179819. PMID 12904361.

- ↑ Keown, Alex (4 February 2020). "FDA Approves Seqirus' Audenz as Vaccine Against Potential Flu Pandemic". BioSpace. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ↑ Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and (29 November 2021). "AUDENZ". FDA. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ↑ Schultz J (2005-11-28). "Bird flu vaccine won't precede pandemic". United Press International. Archived from the original on February 15, 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ Enserick, M. (2005-08-12). "Avian Influenza:'Pandemic Vaccine' Appears to Protect Only at High Doses". American Scientist. 91 (2): 122. doi:10.1511/2003.2.122. Archived from the original on 2006-02-28. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ Walker K (2006-01-27). "Two H5N1 human vaccine trials to begin". Science Daily. Archived from the original on 2006-02-14. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ Gao W, Soloff AC, Lu X, Montecalvo A, Nguyen DC, Matsuoka Y, Robbins PD, Swayne DE, Donis RO, Katz JM, Barratt-Boyes SM, Gambotto A (2006). "Protection of Mice and Poultry from Lethal H5N1 Avian Influenza Virus through Adenovirus-Based Immunization". J. Virol. 80 (4): 1959–1964. doi:10.1128/JVI.80.4.1959-1964.2006. PMC 1367171. PMID 16439551.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 United States Agency for International Development (2006). "Avian Influenza Response: Key Actions to Date". Archived from the original on 2006-04-17. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ United States Department of Health and Human Services (2002). "Pandemicflu.gov Monitoring outbreaks". Archived from the original on 2006-04-26. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ Medline Plus (2006-01-12). "Oseltamivir (Systemic)". National Institutes of Health (NIH). Archived from the original on 2006-04-25. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ Associated Press, "Tamiflu is Set Aside for WHO," The Wall Street Journal, April 20, 2006, p. D6.

- ↑ Integrated Regional Information Networks (2006-04-02). "Middle East: Interview with WHO experts Hassan al-Bushra and John Jabbour". Alertnet Reuters foundation. Archived from the original on 2006-04-07. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ Sendor, Adam B.; Weerasuriya, Dilani; Sapra, Amit (2022). "Avian Influenza". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 31971713. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2022.

- ↑ "Cumulative Number of Confirmed Human Cases for Avian Influenza A/(H5N1) Reported to WHO, 2003–2011" (PDF). World Health Organization (WHO). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-10-27.

- ↑ "Studies Spot Obstacle to Human Transmission of Bird Flu". Forbes. 2006-03-22. Archived from the original on May 23, 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ Brstilo M. (2006-01-19). "Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Croatia Follow-up report No. 4". Archived from the original on 2006-05-14. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ European Food Safety Authority (2006-04-04). "Scientific Statement on Migratory birds and their possible role in the spread of highly pathogenic avian influenza" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-07. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ "Bird flu may be spread indirectly, WHO says". Reuters. Reuters. 2008-01-17. Archived from the original on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ↑ Beigel JH, Farrar J, Han AM, Hayden FG, Hyer R, de Jong MD, Lochindarat S, Nguyen TK, Nguyen TH, Tran TH, Nicoll A, Touch S, Yuen KY; Writing Committee of the World Health Organization (WHO) Consultation on Human Influenza A/H5. (2005). "Avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans". N. Engl. J. Med. 353 (13): 1374–1385. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.730.7890. doi:10.1056/NEJMra052211. PMID 16192482.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Rosenthal E (2006-04-15). "Bird Flu Virus May Be Spread by Smuggling". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-05-20. Retrieved 2006-04-18.

- ↑ Gu, Jiang; Xie, Zhigang; Gao, Zhancheng; Liu, Jinhua; Korteweg, Christine; Ye, Juxiang; Lau, Lok Ting; Lu, Jie; Gao, Zifen; Zhang, Bo; McNutt, Michael A. (2007-09-29). "H5N1 infection of the respiratory tract and beyond: a molecular pathology study". The Lancet. 370 (9593): 1137–1145. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61515-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7159293. PMID 17905166.

- ↑ "Chile detects first case of bird flu in a human". Reuters. 2023-03-29. Retrieved 2023-03-30.

- ↑ "North Korea confirms bird flu outbreak at duck farm". Yonhap News. 2013-05-20. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07.

- ↑ Viseshakul, Nareerat; Thanawongnuwech, Roongroje; Amonsin, Alongkorn; Suradhat, Sanipa; Payungporn, Sunchai; Keawchareon, Juthatip; Oraveerakul, Kanisak; Wongyanin, Piya; Plitkul, Sukanya; Theamboonlers, Apiradee; Poovorawan, Yong (October 2004). "The genome sequence analysis of H5N1 avian influenza A virus isolated from the outbreak among poultry populations in Thailand". Virology. 328 (2): 169–176. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2004.06.045. PMID 15464837. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ↑ "Influenza Research Database - Strain A/chicken/Nakorn-Patom/Thailand/CU-K2/2004(H5N1)". www.fludb.org. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ Payungporn S, Chutinimitkul S, Chaisingh A, Damrongwantanapokin S, Nuansrichay B, Pinyochon W, Amonsin A, Donis RO, Theamboonlers A, Poovorawan T (2006). "Discrimination between Highly Pathogenic and Low Pathogenic H5 Avian Influenza A Viruses". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (4): 700–701. doi:10.3201/eid1204.051427. PMC 3294708. PMID 16715581.

- ↑ Parker-Pope T (2009-11-05). "The Cat Who Got Swine Flu". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ↑ Bernd Sebastian Kamps; Christian Hoffmann. "Zanamivir". Influenza Report. Archived from the original on 2006-10-27. Retrieved 2006-10-15.

- ↑ Zheng B.-J. (June 10, 2008). "Delayed antiviral plus immunomodulator treatment still reduces mortality in mice infected by high inoculum of influenza A/H5N1 virus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (23): 8091–8096. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.8091Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711942105. PMC 2430364. PMID 18523003.

- ↑ "Oseltamivir-resistant H5N1 virus isolated from Vietnamese girl". Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP). October 14, 2005. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-15.

- ↑ "U.N. Says Bird Flu Awareness Increases". National Public Radio (NPR). October 12, 2006. Archived from the original on 2008-04-14. Retrieved 2006-10-15.[dead link]

- ↑ Collins PJ, Haire LF, Lin YP, Liu J, Russell RJ, Walker PA, Skehel JJ, Martin SR, Hay AJ, Gamblin SJ (2008). "Crystal structures of oseltamivir-resistant influenza virus neuraminidase mutants". Nature. 453 (7199): 1258–1261. Bibcode:2008Natur.453.1258C. doi:10.1038/nature06956. PMID 18480754. S2CID 4383625.

- ↑ Garcia-Sosa AT, Sild S, Maran U (2008). "Design of Multi-Binding-Site Inhibitors, Ligand Efficiency, and Consensus Screening of Avian Influenza H5N1 Wild-Type Neuraminidase and of the Oseltamivir-Resistant H274Y Variant". J. Chem. Inf. Model. 48 (10): 2074–2080. doi:10.1021/ci800242z. PMID 18847186.

- ↑ Harmon, Katherine (2011-09-19). "What Will the Next Influenza Pandemic Look Like?". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 2012-03-02. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

- ↑ David Malakoff (March 30, 2012). "Breaking News: NSABB Reverses Position on Flu Papers". Science Insider. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ Nell Greenfieldboyce (April 24, 2012). "Bird Flu Scientist has Applied for Permit to Export Research". NPR. Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ Nell Greenfieldboyce (June 21, 2012). "Journal Publishes Details on Contagious Bird Flu Created in Lab". National Public Radio (NPR). Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ "H5N1" (Special Issue). Science. June 21, 2012. Archived from the original on June 25, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ Herfst, S.; Schrauwen, E. J. A.; Linster, M.; Chutinimitkul, S.; De Wit, E.; Munster, V. J.; Sorrell, E. M.; Bestebroer, T. M.; Burke, D. F.; Smith, D. J.; Rimmelzwaan, G. F.; Osterhaus, A. D. M. E.; Fouchier, R. A. M. (2012). "Airborne Transmission of Influenza A/H5N1 Virus Between Ferrets". Science. 336 (6088): 1534–1541. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1534H. doi:10.1126/science.1213362. PMC 4810786. PMID 22723413.

- ↑ Brown, Eryn (June 21, 2012). "Scientists create bird flu that spreads easily among mammals". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 23, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Chinese Scientists Create New Mutant Bird-Flu Virus" Archived 2014-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, Wired, May 2, 2013

- ↑ "Scientists Resume Efforts to Create Deadly Flu Virus, with US Government's Blessing". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2021-03-01. Retrieved 2022-02-17.

- ↑ "From anthrax to bird flu – the dangers of lax security in disease-control labs". TheGuardian.com. 18 July 2014. Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ↑ State.gov Archived 2006-09-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Newswire Archived May 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "BMO Financial Group". .bmo.com. Archived from the original on 2009-05-03. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ↑ India eNews[usurped] article Pakistani poultry industry demands 10-year tax holiday published May 7, 2006 says "Pakistani poultry farmers have sought a 10-year tax exemption to support their dwindling business after the detection of the H5N1 strain of bird flu triggered a fall in demand and prices, a poultry trader said."

- ↑ International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) Archived 2006-04-27 at the Wayback Machine Scientific Seminar on Avian Influenza, the Environment and Migratory Birds on 10–11 April 2006 published 14 April 2006.

- ↑ McNeil Jr., Donald G. (March 28, 2006). "The response to bird flu: Too much or not enough? UN expert stands by his dire warnings". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008.

- ↑ "China province near coronavirus outbreak kills 18,000 chickens infected by a separate flu". Newsweek. 2020-02-02. Archived from the original on 2020-12-03. Retrieved 2020-12-03.

Sources

- Analysis of the efficacy of an adjuvant-based inactivated pandemic H5N1 influenza virus vaccine. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00705-019-04147-7 Archived 2022-02-04 at the Wayback Machine Ainur NurpeisovaEmail authorMarkhabat KassenovNurkuisa RametovKaissar TabynovGourapura J. RenukaradhyaYevgeniy VolginAltynay SagymbayAmanzhol MakbuzAbylay SansyzbayBerik Khairullin

External links

| Wikinews has news related to: |

- Influenza Research Database – Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.

- WHO World Health Organization

- WHO's Avian Flu Facts Sheet for 2006

- Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and Response Guide to WHO's H5N1 pages

- Avian Influenza Resources (updated) – tracks human cases and deaths

- National Influenza Pandemic Plans

- WHO Collaborating Centres and Reference Laboratories Centers, names, locations, and phone numbers

- FAO Avian Influenza portalArchived 2012-01-26 at the Wayback Machine Information resources, animations, videos, photos

- FAO Archived 2006-05-11 at the Wayback Machine Food and Agriculture Organisation – Bi-weekly Avian Influenza Maps – tracks animal cases and deaths

- FAO Bird Flu disease card Archived 2005-03-16 at the Wayback Machine

- FAO Socio-Economic impact of AI Projects, Information resources

- OIE World Organisation for Animal Health – tracks animal cases and deaths

- Official outbreak reports by countryArchived 2012-12-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Official outbreak reports by week

- Chart of outbreaks by countryArchived 2012-04-19 at the Wayback Machine

- European Union

- Health-EU Portal Archived 2013-09-22 at the Wayback Machine EU response to Avian Influenza.

- Avian influenza – Q & A's factsheet from European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

- United Kingdom

- Exotic Animal Disease Generic Contingency PlanArchived 2013-04-20 at the Wayback Machine – DEFRA generic contingency plan for controlling and eradicating an outbreak of an exotic animal disease. PDF hosted by BBC.

- UK Influenza Pandemic Contingency PlanArchived 2012-07-05 at the Wayback Machine by the National Health Service – a government entity. PDF hosted by BBC

- UK Department of Health Archived 2009-07-09 at the Wayback Machine

- United States

- Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy Archived 2013-06-17 at the Wayback Machine Avian Influenza (Bird Flu): Implications for Human Disease – An overview of Avian Influenza

- PandemicFlu.Gov Archived 2009-04-26 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Government's avian flu information site

- USAID U.S. Agency for International Development – Avian Influenza Response

- CDC Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – responsible agency for avian influenza in humans in US – Facts About Avian Influenza (Bird Flu) and Avian Influenza A (H5N1) Virus

- USGS – NWHC National Wildlife Health Center – responsible agency for avian influenza in animals in US

- Wildlife Disease Information Node A part of the National Biological Information Infrastructure and partner of the NWHC, this agency collects and distributes news and information about wildlife diseases such as avian influenza and coordinates collaborative information sharing efforts.

- HHS U.S. Department of Health & Human Services's Pandemic Influenza Plan

- Webarchive template wayback links

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- CS1 maint: unfit URL

- CS1: long volume value

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from July 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles with 'species' microformats

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Portal templates with all redlinked portals

- Influenza A virus subtype H5N1

- Bird diseases

- Subtypes of Influenza A virus