Hepatitis B vaccine

Hepatitis B pre-filled syringe | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | Hepatitis B virus |

| Type | Subunit |

| Names | |

| Trade names | Recombivax HB, Engerix-B, Heplisav-B, others |

| Clinical data | |

| Main uses | Prevent hepatitis B[1] |

| Side effects | Pain at the site of injection[1] |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | Intramuscular (IM) |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607014 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

Hepatitis B vaccine is a vaccine that prevents hepatitis B.[1] It is given by injection, usually into muscle, but can be given under the skin in people with bleeding disorders.[6] In healthy people routine immunization results in more than 95% of people being protected.[1] Blood testing to verify that the vaccine has worked is recommended in those at high risk.[1]

The first dose is recommended within 24 hours of birth with either two or three more doses given after that.[1] This includes in those with poor immune function such as from HIV/AIDS and those born premature.[1] It is also recommended that health-care workers be vaccinated.[7] Additional doses may be needed in people with poor immune function but are not necessary for most people.[1] In those who have been exposed to the hepatitis B virus (HBV) but not immunized, hepatitis B immune globulin should be given in addition to the vaccine.[1]

Serious side effects from the hepatitis B vaccine are very uncommon.[1] Pain may occur at the site of injection.[1] It is safe for use during pregnancy or while breastfeeding.[1] It has not been linked to Guillain–Barré syndrome.[1] The hepatitis B vaccines are produced with recombinant DNA techniques.[1] They are available both by themselves and in combination with other vaccines.[1]

The first hepatitis B vaccine was approved in the United States in 1981.[8] It has been available since 1982.[9] A recombinant version came to market in 1986.[1] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[10] As of 2014[update], the wholesale cost in the developing world is US$0.58–13.20 per dose.[11] In the United States it costs US$50–100.[12]

Medical uses

Hepatitis B vaccination, hepatitis B immunoglobulin, and the combination of hepatitis B vaccine plus hepatitis B immunoglobulin, all are considered as preventive for babies born to mothers infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV).[13] The combination is superior for protecting these infants.[13] The vaccine during pregnancy is not considered to be valuable in protecting babies of the infected mothers.[14] Hepatitis B immunoglobulin before birth has not been well studied.[15]

In the United States vaccination is recommended for nearly all babies at birth.[16] Many countries now routinely vaccinate infants against hepatitis B. In countries with high rates of hepatitis B infection, vaccination of newborns has not only reduced the risk of infection, but has also led to a marked reduction in liver cancer. This was reported in Taiwan where the implementation of a nationwide hepatitis B vaccination program in 1984 was associated with a decline in the incidence of childhood hepatocellular carcinoma.[17]

In the UK, the vaccine is offered to men who have sex with men (MSM), usually as part of a sexual health check-up. A similar situation is in operation in Ireland.[18]

In many areas, vaccination against hepatitis B is also required for all health-care and laboratory staff.[19] Both types of the vaccine, the plasma-derived vaccine (PDV) and recombinant vaccine (RV), seems to be able to elicit similar protective anti-HBs levels.[7]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued recommendations for vaccination against hepatitis B among patients with diabetes mellitus.[20] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends a pentavalent vaccine, combining vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis and Haemophilus influenzae type B with the vaccine against hepatitis B.[medical citation needed] There is not yet sufficient evidence on how effective this pentavalent vaccine is in relation to the individual vaccines.[21] A pentavalent vaccine combining vaccines against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B, and poliomyelitis is approved in the U.S. and is recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP).[22][23][24]

Effectiveness

Following the primary course of three vaccinations, a blood test may be taken after an interval of 1–4 months to establish if there has been an adequate response, which is defined as an anti-hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-Hbs) antibody level above 100 mIU/ml. Such a full response occurs in about 85–90% of individuals.[25]

An antibody level between 10 and 100 mIU/ml is considered a poor response, and these people should receive a single booster vaccination at this time, but do not need further retesting.[25]

People who fail to respond (anti-Hbs antibody level below 10 mIU/ml) should be tested to exclude current or past Hepatitis B infection, and given a repeat course of three vaccinations, followed by further retesting 1–4 months after the second course. Those who still do not respond to a second course of vaccination may respond to intradermal administration[26] or to a high dose vaccine[27] or to a double dose of a combined hepatitis A and B vaccine.[28] Those who still fail to respond will require hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) if later exposed to the hepatitis B virus.[25]

Poor responses are mostly associated with being over the age of 40 years, obesity, celiac disease, and tobacco smoking,[26][29] and also in alcoholics, especially if with advanced liver disease.[30] People who are immunosuppressed or on dialysis may not respond as well and require larger or more frequent doses of vaccine.[25] At least one study suggests that hepatitis B vaccination is less effective in patients with HIV.[31]

Duration

It is believed that the hepatitis B vaccine provides indefinite protection. However, it was previously believed and suggested that the vaccination would only provide effective coverage of between five and seven years,[32][33] but subsequently it has been appreciated that long-term immunity derives from immunological memory which outlasts the loss of antibody levels and hence subsequent testing and administration of booster doses is not required in successfully vaccinated immunocompetent individuals.[34][35] Hence with the passage of time and longer experience, protection has been shown for at least 25 years in those who showed an adequate initial response to the primary course of vaccinations,[36] and UK guidelines now suggest that people who respond to the vaccine and are at risk of occupational exposure, such as for healthcare workers, a single booster is recommended five years after initial immunization.[25]

Dosage

The defined daily dose is not established[37]

Side effects

Serious side effects from the hepatitis B vaccine are very rare.[1] Pain may occur at the site of injection.[1] It is generally considered safe for use, during pregnancy or while breastfeeding.[1][38] It has not been linked to Guillain–Barré syndrome.[1]

Multiple sclerosis

Several studies have looked for an association between recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and multiple sclerosis (MS) in adults.[39] Most studies do not support a causal relationship between hepatitis B vaccination and demyelinating diseases such as MS.[39][40][41] A 2004 study reported a significant increase in risk within three years of vaccination. Some of these studies were criticized for methodological problems.[42] This controversy created public misgivings about HB vaccination, and hepatitis B vaccination in children remained low in several countries. A 2006 study concluded that evidence did not support an association between HB vaccination and sudden infant death syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome, or multiple sclerosis.[43] A 2007 study found that the vaccination does not seem to increase the risk of a first episode of MS in childhood.[44] Hepatitis B vaccination has not been linked to onset of autoimmune diseases in adulthood.[45]

Usage

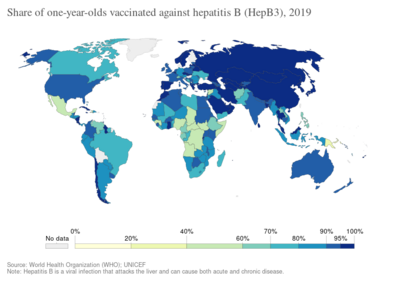

The following is a list of countries by the percentage of infants receiving three doses of hepatitis B vaccine as published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017.[46]

| Hepatitis B (HepB3) immunization coverage among one-year-olds worldwide | |

|---|---|

| Country | Coverage % |

| Afghanistan | 65 |

| Albania | 99 |

| Algeria | 91 |

| Andorra | 98 |

| Angola | 52 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 95 |

| Argentina | 86 |

| Armenia | 94 |

| Australia | 95 |

| Austria | 90 |

| Azerbaijan | 95 |

| Bahamas | 94 |

| Bahrain | 98 |

| Bangladesh | 97 |

| Barbados | 90 |

| Belarus | 98 |

| Belgium | 97 |

| Belize | 88 |

| Benin | 82 |

| Bhutan | 98 |

| Bolivia (Plurinational State of) | 83 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 77 |

| Botswana | 95 |

| Brazil | 93 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 99 |

| Bulgaria | 92 |

| Burkina Faso | 91 |

| Burundi | 91 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 84 |

| Cabo Verde | 86 |

| Cambodia | 93 |

| Cameroon | 86 |

| Canada | 69 |

| Central African Republic | 47 |

| Chad | 41 |

| Chile | 93 |

| China | 99 |

| Colombia | 92 |

| Comoros | 91 |

| Congo | 69 |

| Cook Islands | 99 |

| Costa Rica | 97 |

| Croatia | 94 |

| Cuba | 99 |

| Cyprus | 97 |

| Czech Republic | 94 |

| Democratic People's Republic of Korea | 97 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 81 |

| Djibouti | 68 |

| Dominica | 91 |

| Dominican Republic | 81 |

| Ecuador | 84 |

| Egypt | 94 |

| El Salvador | 85 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 25 |

| Eritrea | 95 |

| Estonia | 92 |

| Eswatini | 90 |

| Ethiopia | 73 |

| Fiji | 99 |

| France | 90 |

| Gabon | 75 |

| Gambia | 92 |

| Georgia | 91 |

| Germany | 87 |

| Ghana | 99 |

| Greece | 96 |

| Grenada | 96 |

| Guatemala | 82 |

| Guinea | 45 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 87 |

| Guyana | 97 |

| Haiti | 58 |

| Honduras | 97 |

| India | 88 |

| Indonesia | 79 |

| Iran (Islamic Republic of) | 99 |

| Iraq | 63 |

| Ireland | 95 |

| Israel | 97 |

| Italy | 94 |

| Jamaica | 93 |

| Jordan | 99 |

| Kazakhstan | 99 |

| Kenya | 82 |

| Kiribati | 90 |

| Kuwait | 99 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 92 |

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 85 |

| Latvia | 98 |

| Lebanon | 78 |

| Lesotho | 93 |

| Liberia | 86 |

| Libya | 94 |

| Lithuania | 94 |

| Luxembourg | 94 |

| Madagascar | 74 |

| Malawi | 88 |

| Malaysia | 98 |

| Maldives | 99 |

| Mali | 66 |

| Malta | 88 |

| Marshall Islands | 82 |

| Mauritania | 81 |

| Mauritius | 96 |

| Mexico | 93 |

| Micronesia (Federated States of) | 80 |

| Monaco | 99 |

| Mongolia | 99 |

| Montenegro | 73 |

| Morocco | 99 |

| Mozambique | 80 |

| Myanmar | 89 |

| Namibia | 88 |

| Nauru | 87 |

| Nepal | 90 |

| Netherlands | 92 |

| New Zealand | 94 |

| Nicaragua | 98 |

| Niger | 81 |

| Nigeria | 42 |

| Niue | 99 |

| Oman | 99 |

| Pakistan | 75 |

| Palau | 98 |

| Panama | 81 |

| Papua New Guinea | 56 |

| Paraguay | 91 |

| Peru | 83 |

| Philippines | 88 |

| Poland | 95 |

| Portugal | 98 |

| Qatar | 97 |

| Republic of Korea | 98 |

| Republic of Moldova | 89 |

| Romania | 92 |

| Russian Federation | 97 |

| Rwanda | 98 |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | 98 |

| Saint Lucia | 80 |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 99 |

| Samoa | 73 |

| San Marino | 86 |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | 95 |

| Saudi Arabia | 98 |

| Senegal | 91 |

| Serbia | 93 |

| Seychelles | 98 |

| Sierra Leone | 90 |

| Singapore | 96 |

| Slovakia | 96 |

| Solomon Islands | 99 |

| Somalia | 42 |

| South Africa | 66 |

| Spain | 93 |

| Sri Lanka | 99 |

| Sudan | 95 |

| Suriname | 81 |

| Swaziland | 98 |

| Sweden | 76 |

| Syrian Arab Republic | 52 |

| Tajikistan | 96 |

| Thailand | 99 |

| The former Yugoslav republic of Macedonia | 91 |

| Timor-Leste | 76 |

| Togo | 90 |

| Tonga | 81 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 89 |

| Tunisia | 98 |

| Turkey | 96 |

| Turkmenistan | 99 |

| Tuvalu | 96 |

| Uganda | 85 |

| Ukraine | 52 |

| United Arab Emirates | 98 |

| United Republic of Tanzania | 97 |

| United States of America | 93 |

| Uruguay | 95 |

| Uzbekistan | 99 |

| Vanuatu | 85 |

| Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) | 84 |

| Viet Nam | 94 |

| Yemen | 68 |

| Zambia | 94 |

| Zimbabwe | 89 |

History

In 1963, the American physician/geneticist Baruch Blumberg discovered what he called the "Australia Antigen" (now called HBsAg) in the serum of an Australian Aboriginal person.[47] In 1968, this protein was found to be part of the virus that causes "serum hepatitis" (hepatitis B) by virologist Alfred Prince.[48] The American microbiologist/vaccinologist Maurice Hilleman at Merck used three treatments (pepsin, urea and formaldehyde) of blood serum together with rigorous filtration to yield a product that could be used as a safe vaccine. Hilleman hypothesized that he could make an HBV vaccine by injecting patients with hepatitis B surface protein. In theory, this would be very safe, as these excess surface proteins lacked infectious viral DNA. The immune system, recognizing the surface proteins as foreign, would manufacture specially shaped antibodies, custom-made to bind to, and destroy, these proteins. Then, in the future, if the patient were infected with HBV, the immune system could promptly deploy protective antibodies, destroying the viruses before they could do any harm.[49]

Hilleman collected blood from gay men and intravenous drug users—groups known to be at risk for viral hepatitis. This was in the late 1970s, when HIV was yet unknown to medicine. In addition to the sought-after hepatitis B surface proteins, the blood samples likely contained HIV. Hilleman devised a multistep process to purify this blood so that only the hepatitis B surface proteins remained. Every known virus was killed by this process, and Hilleman was confident that the vaccine was safe.[49]

The first large-scale trials for the blood-derived vaccine were performed on gay men, in accordance with their high-risk status. Later, Hilleman's vaccine was falsely blamed for igniting the AIDS epidemic. (See Wolf Szmuness) But, although the purified blood vaccine seemed questionable, it was determined to have indeed been free of HIV. The purification process had destroyed all viruses—including HIV.[49] The vaccine was approved in 1981.[citation needed]

The blood-derived hepatitis B vaccine was withdrawn from the marketplace in 1986, when Pablo DT Valenzuela, Research Director of Chiron Corporation, succeeded in making the antigen in yeast and invented the world's first recombinant vaccine.[50] The recombinant vaccine was developed by inserting the HBV gene that codes for the surface protein into the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. This allows the yeast to produce only the noninfectious surface protein, without any danger of introducing actual viral DNA into the final product.[49] This is the vaccine still in use today.[when?]

In 1976, Blumberg won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on hepatitis B (sharing it with Daniel Carleton Gajdusek for his work on kuru). In 2002, Blumberg published a book, Hepatitis B: The Hunt for a Killer Virus.[51] In the book, according to Paul A. Offit—Hilleman's biographer and an accomplished vaccinologist himself—Blumberg...

... claimed that the hepatitis B vaccine was his invention. Maurice Hilleman's name is mentioned once.... Blumberg failed to mention that it was Hilleman who had figured out how to inactivate hepatitis B virus, how to kill all other possible contaminating viruses, how to completely remove every other protein found in human blood, and how to do all of this while retaining the structural integrity of the surface protein. Blumberg had identified Australia antigen, an important first step. But all of the other steps—the ones critical to making a vaccine—belonged to Hilleman. Later, Hilleman recalled, "I think that [Blumberg] deserves a lot of credit, but he doesn't want to give credit to the other guy."[52]

Robert Purcell, a virologist, has emphasized the importance of the hepatitis B vaccine; in figuring out the hepatitis viruses, generally.[53][54]

In 2017, a two-dose HBV vaccine for adults, Heplisav-B gained U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval.[55] It uses recombinant HB surface antigen, similar to previous vaccines, but includes a novel CpG 1018 adjuvant, a 22-mer phosphorothioate-linked oligodeoxynucleotide. It was non-inferior with respect to immunogenicity.[56]

Manufacture

The vaccine contains one of the viral envelope proteins, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). It is produced by yeast cells, into which the gene for HBsAg has been inserted.[57] Afterward an immune system antibody to HBsAg is established in the bloodstream. The antibody is known as anti-HBs. This antibody and immune system memory then provide immunity to HBV infection.[58]

Brand names

The common brands available are Recombivax HB (Merck),[59] Engerix-B (GSK),[60] Elovac B (Human Biologicals Institute, a division of Indian Immunologicals Limited), Genevac B (Serum Institute), Shanvac B, Heplisav-B,[55] etc. These vaccines are given by the intramuscular route.

Twinrix (GSK) is a vaccine against hepatitis A and hepatitis B.[61][62]

Pediarix is a vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B, and poliomyelitis.[63]

Vaxelis is a vaccine against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, Haemophilus influenzae type B (Meningococcal Protein Conjugate), and hepatitis B.[64][65]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 World Health Organization (July 2017). "Hepatitis B vaccines: WHO position paper – July 2017". Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 92 (27): 369–92. hdl:10665/255873. PMID 28685564.

- Lay summary in: (PDF) https://www.who.int/immunization/policy/position_papers/who_pp_hepb_2017_summary.pdf.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help)

- Lay summary in: (PDF) https://www.who.int/immunization/policy/position_papers/who_pp_hepb_2017_summary.pdf.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Hepatitis b adult vaccine Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 27 April 2020. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ "Engerix B SmPC". Datapharm. 24 April 2017. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ↑ "HBVaxPro SmPC". Datapharm. 12 March 2019. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ↑ "Hepatitis B Vaccine Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. 1 September 2019. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ↑ Lampiris, Harry W.; maddix, Daniel S. (2020). "Appendix: Vaccines, immune globulins, and other complex biologic products". In Katzung, Bertram G.; Trevor, Anthony J. (eds.). Basic and Clinical Pharmacology (15th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 1228. ISBN 978-1-260-45231-0. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Chen W, Gluud C (October 2005). "Vaccines for preventing hepatitis B in health-care workers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD000100. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000100.pub3. PMID 16235273.

- ↑ Moticka, Edward (25 November 2015). A Historical Perspective on Evidence-Based Immunology. p. 336. ISBN 9780123983756.

- ↑ Van Damme, Pierre; Ward, John W.; Shovel, Daniel; Zanetti, Alessandro (2018). "25. Hepatitis B vaccines". In Plotkin, Stanley A.; Orenstein, Walter; Offit, Paul A.; Edwards, Kathryn M. (eds.). Vaccines (Seventh ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 342-362. ISBN 978-0-323-35761-6. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ↑ "Vaccine, Hepatitis B". International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richart (2015). Tarascon Pocket Pharmacopoeia 2015 Deluxe Lab-Coat Edition. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 314. ISBN 9781284057560.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lee C, Gong Y, Brok J, Boxall EH, Gluud C (April 2006). "Hepatitis B immunisation for newborn infants of hepatitis B surface antigen-positive mothers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD004790. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004790.pub2. PMID 16625613.

- ↑ Sangkomkamhang US, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M (November 2014). "Hepatitis B vaccination during pregnancy for preventing infant infection". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD007879. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007879.pub3. PMC 7185858. PMID 25385500.

- ↑ Eke AC, Eleje GU, Eke UA, Xia Y, Liu J (February 2017). "Hepatitis B immunoglobulin during pregnancy for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2: CD008545. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008545.pub2. PMC 6464495. PMID 28188612.

- ↑ Committee On Infectious Diseases; Committee On Fetus And Newborn (September 2017). "Elimination of Perinatal Hepatitis B: Providing the First Vaccine Dose Within 24 Hours of Birth". Pediatrics. 140 (3): e20171870. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-1870. PMID 28847980.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Chang MH, Chen CJ, Lai MS, Hsu HM, Wu TC, Kong MS, Liang DC, Shau WY, Chen DS (June 1997). "Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children. Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (26): 1855–9. doi:10.1056/NEJM199706263362602. PMID 9197213.

- ↑ "Hepatitis B vaccine". Nhs.uk. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (2006). "Chapter 12 Immunisation of healthcare and laboratory staff—Hepatitis B". Immunisation Against Infectious Disease 2006 ("The Green Book") (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Stationery Office. p. 468. ISBN 978-0-11-322528-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2008.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (December 2011). "Use of hepatitis B vaccination for adults with diabetes mellitus: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)" (PDF). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 60 (50): 1709–11. PMID 22189894. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Bar-On ES, Goldberg E, Hellmann S, Leibovici L (April 2012). "Combined DTP-HBV-HIB vaccine versus separately administered DTP-HBV and HIB vaccines for primary prevention of diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae B (HIB)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 4 (4): CD005530. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005530.pub3. PMID 22513932.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (March 2003). "FDA licensure of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis adsorbed, hepatitis B (recombinant), and poliovirus vaccine combined, (PEDIARIX) for use in infants". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 52 (10): 203–4. PMID 12653460.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) (October 2008). "Licensure of a diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis adsorbed and inactivated poliovirus vaccine and guidance for use as a booster dose" (PDF). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 57 (39): 1078–9. PMID 18830212. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Schillie S, Vellozzi C, Reingold A, Harris A, Haber P, Ward JW, Nelson NP (January 2018). "Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices" (PDF). MMWR Recomm Rep. 67 (1): 1–31. doi:10.15585/mmwr.rr6701a1. PMC 5837403. PMID 29939980. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (2006). "Chapter 18: Hepatitis B". Immunisation Against Infectious Disease 2006 ("The Green Book") (3rd edition (Chapter 18 revised 10 October 2007) ed.). Edinburgh: Stationery Office. p. 468. ISBN 978-0-11-322528-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2013.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Filippelli M, Lionetti E, Gennaro A, Lanzafame A, Arrigo T, Salpietro C, La Rosa M, Leonardi S (August 2014). "Hepatitis B vaccine by intradermal route in non responder patients: an update". World J. Gastroenterol. (Review). 20 (30): 10383–94. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10383. PMC 4130845. PMID 25132754.

- ↑ Levitz RE, Cooper BW, Regan HC (February 1995). "Immunization with high-dose intradermal recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in healthcare workers who failed to respond to intramuscular vaccination". Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 16 (2): 88–91. doi:10.1086/647062. PMID 7759824.

- ↑ Cardell K, Akerlind B, Sällberg M, Frydén A (August 2008). "Excellent response rate to a double dose of the combined hepatitis A and B vaccine in previous nonresponders to hepatitis B vaccine". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 198 (3): 299–304. doi:10.1086/589722. PMID 18544037.

- ↑ Roome AJ, Walsh SJ, Cartter ML, Hadler JL (1993). "Hepatitis B vaccine responsiveness in Connecticut public safety personnel". JAMA. 270 (24): 2931–4. doi:10.1001/jama.270.24.2931. PMID 8254852.

- ↑ Rosman AS, Basu P, Galvin K, Lieber CS (September 1997). "Efficacy of a high and accelerated dose of hepatitis B vaccine in alcoholic patients: a randomized clinical trial". The American Journal of Medicine. 103 (3): 217–22. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00132-0. PMID 9316554.

- ↑ Pasricha N, Datta U, Chawla Y, Singh S, Arora SK, Sud A, Minz RW, Saikia B, Singh H, James I, Sehgal S (March 2006). "Immune responses in patients with HIV infection after vaccination with recombinant Hepatitis B virus vaccine". BMC Infectious Diseases. 6: 65. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-6-65. PMC 1525180. PMID 16571140. Cold or Flu like symptoms can develop after receiving the vaccine, but these are short lived. As with any injection, the muscle can become tender around the injection point for some time afterwards

- ↑ Krugman S, Davidson M (1987). "Hepatitis B vaccine: prospects for duration of immunity". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 60 (4): 333–9. PMC 2590237. PMID 3660859.

- ↑ Petersen KM, Bulkow LR, McMahon BJ, Zanis C, Getty M, Peters H, Parkinson AJ (July 2004). "Duration of hepatitis B immunity in low risk children receiving hepatitis B vaccinations from birth" (Free full text). The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 23 (7): 650–5. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000130952.96259.fd. PMID 15247604. Archived from the original on 5 June 2015.

- ↑ Gabbuti A, Romanò L, Blanc P, Meacci F, Amendola A, Mele A, Mazzotta F, Zanetti AR (April 2007). "Long-term immunogenicity of hepatitis B vaccination in a cohort of Italian healthy adolescents". Vaccine. 25 (16): 3129–32. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.045. PMID 17291637.

- ↑ "Are booster immunisations needed for lifelong hepatitis B immunity? European Consensus Group on Hepatitis B Immunity". Lancet. 355 (9203): 561–5. February 2000. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)07239-6. PMID 10683019.

- ↑ Van Damme P, Van Herck K (March 2007). "A review of the long-term protection after hepatitis A and B vaccination". Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 5 (2): 79–84. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2006.04.004. PMID 17298912.

- ↑ "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ↑ Borgia G, Carleo MA, Gaeta GB, Gentile I (September 2012). "Hepatitis B in pregnancy". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (34): 4677–83. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i34.4677. PMC 3442205. PMID 23002336.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Martínez-Sernández V, Figueiras A (August 2013). "Central nervous system demyelinating diseases and recombinant hepatitis B vaccination: a critical systematic review of scientific production". Journal of Neurology. 260 (8): 1951–9. doi:10.1007/s00415-012-6716-y. PMID 23086181.

- ↑ "FAQs about Hepatitis B Vaccine (Hep B) and Multiple Sclerosis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 9 October 2009. Archived from the original on 10 November 2009.

- ↑ Mouchet J, Salvo F, Raschi E, Poluzzi E, Antonazzo IC, De Ponti F, Bégaud B (March 2018). "Hepatitis B vaccination and the putative risk of central demyelinating diseases - A systematic review and meta-analysis". Vaccine. 36 (12): 1548–55. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.036. PMID 29454521.

- ↑ Hernán MA, Jick SS, Olek MJ, Jick H (September 2004). "Recombinant hepatitis B vaccine and the risk of multiple sclerosis: a prospective study". Neurology. 63 (5): 838–42. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000138433.61870.82. PMID 15365133.

- ↑ Zuckerman JN (February 2006). "Protective efficacy, immunotherapeutic potential, and safety of hepatitis B vaccines". Journal of Medical Virology. 78 (2): 169–77. doi:10.1002/jmv.20524. PMID 16372285.

- ↑ Mikaeloff Y, Caridade G, Rossier M, Suissa S, Tardieu M (December 2007). "Hepatitis B vaccination and the risk of childhood-onset multiple sclerosis". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 161 (12): 1176–82. doi:10.1001/archpedi.161.12.1176. PMID 18056563.

- ↑ Elwood JM, Ameratunga R (September 2018). "Autoimmune diseases after hepatitis B immunization in adults: Literature review and meta-analysis, with reference to 'autoimmune/autoinflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants' (ASIA)". Vaccine (Review). 36 (38): 5796–5802. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.07.074. PMID 30100071.

- ↑ "Hepatitis B (HepB3) Immunization coverage estimates by country". WHO. Archived from the original on 11 May 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ↑ Blumberg BS, Alter HJ, Visnich S (February 1965). "A "New" Antigen In Leukemia Sera". JAMA. 191 (7): 541–6. doi:10.1001/jama.1965.03080070025007. PMID 14239025.

- ↑ Howard, Colin; Zuckerman, Arie J. (1979). Hepatitis viruses of man. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-0-12-782150-4.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 "World Hepatitis Day: The History of the Hepatitis B Vaccine | Planned Parenthood Advocates of Arizona". Blog.advocatesaz.org. 26 July 2012. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ Fisher, Lawrence M. (13 October 1986). "Biotechnology Spotlight Now Shines On Chiron". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017.

- ↑ Blumberg, Baruch (2002), Hepatitis B: The Hunt for a Killer Virus, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Offit, Paul A. (2007). Vaccinated:One Man's Quest to Defeat the World's Deadliest Diseases. New York: Smithsonian Books/Collins. pp. 135–136.

- ↑ "Profile: Biochemist Barush S. Blumberg: The Search for Extreme Life" (PDF). Scientific American: 31–32. July 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ↑ Gerlich WH (July 2013). "Medical virology of hepatitis B: how it began and where we are now". Virology Journal. 10: 239. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-10-239. PMC 3729363. PMID 23870415.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "Heplisav-B". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 April 2019. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ↑ Dynavax Technologies Corp. "Heplisav-B [Hepatitis B Vaccine (Recombinant), Adjuvanted] label" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ↑ "Hepatitis B Vaccine from Merck". Archived from the original on 21 April 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ↑ "CDC Viral Hepatitis". Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 24 July 2009. Archived from the original on 20 October 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

- ↑ "Recombivax HB". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ↑ "Engerix-B". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ↑ "Hepatitis A & hepatitis B recombinant vaccine - Drug Summary". www.pdr.net. Prescriber's Digital Reference. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019.

- ↑ "Twinrix". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 April 2019. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ↑ "Pediarix". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 February 2018. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ↑ "Vaxelis EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 19 February 2019. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ↑ "Vaxelis". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 October 2019. STN 125563. Archived from the original on 17 October 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

External links

| Identifiers: |

|---|

- "Hepatitis B Vaccine Information Statement". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Hepatitis B Vaccines at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Pages with non-numeric formatnum arguments

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- CS1 errors: missing title

- CS1 errors: bare URL

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- Use dmy dates from October 2019

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug

- Chemical articles without CAS registry number

- Articles without EBI source

- Chemical pages without ChemSpiderID

- Chemical pages without DrugBank identifier

- Articles without KEGG source

- Articles without InChI source

- Articles without UNII source

- Drugs missing an ATC code

- Drugboxes which contain changes to verified fields

- Drugs that are a vaccine

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2014

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2019

- All articles with vague or ambiguous time

- Vague or ambiguous time from October 2019

- Chemicals that do not have a ChemSpider ID assigned

- Hepatitis B

- Cancer vaccines

- GlaxoSmithKline brands

- Merck & Co. brands

- Recombinant proteins

- Subunit vaccines

- Vaccines

- World Health Organization essential medicines (vaccines)

- RTT

- RTTVaccine