Swine influenza

| Swine influenza | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Pig influenza, swine flu, hog flu, pig flu | |

| |

| Electron microscope image of the reassorted H1N1 influenza virus photographed at the CDC Influenza Laboratory. The viruses are 80–120 nanometres in diameter.[1] | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Chills, fever, sore throat, muscle pains, severe headache, coughing, weakness, shortness of breath, and general discomfort[2] |

| Types | SIV strains include influenza C and the subtypes of influenza A known as H1N1, H1N2, H2N1, H3N1, H3N2, and H2N3[3] |

| Diagnostic method | CDC recommends real-time PCR as the method of choice for diagnosing H1N1.[4] |

| Prevention | Vaccines are available for different kinds of swine flu. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the new swine flu vaccine for use in the United States on September 15, 2009.[5] |

| Treatment | U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of oseltamivir (Tamiflu) or zanamivir (Relenza) for the treatment and/or prevention of infection with swine influenza viruses; however, the majority of people infected with the virus make a full recovery without requiring medical attention or antiviral drugs.[6] |

Swine influenza is an infection caused by any of several types of swine influenza viruses. Swine influenza virus (SIV) or swine-origin influenza virus (S-OIV) is any strain of the influenza family of viruses that is endemic in pigs.[7] As of 2009, the known SIV strains include influenza C and the subtypes of influenza A known as H1N1, H1N2, H2N1, H3N1, H3N2, and H2N3.[3]

Transmission of the virus from pigs to humans is not common and does not always lead to human flu, often resulting only in the production of antibodies in the blood. If transmission causes human flu, it is called zoonotic swine flu; people with regular exposure to pigs are at increased risk of swine flu infection.[8][9]

Around the mid-20th century, identification of influenza subtypes became possible, allowing accurate diagnosis of transmission to humans. These strains of swine flu rarely pass from human to human. Symptoms of zoonotic swine flu in humans are similar to those of influenza and of influenza-like illness in general, namely chills, fever, sore throat, muscle pains, severe headache, coughing, weakness, shortness of breath, and general discomfort.[7][2]

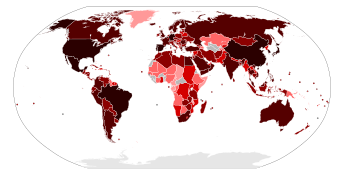

It is estimated that, in the 2009 flu pandemic, 11–21% of the then global population (of about 6.8 billion), or around 700 million to 1.4 billion people, contracted the illness—more in absolute terms than the Spanish flu pandemic. There were 18,449 confirmed fatalities. However, in a 2012 study, the CDC estimated more than 284,000 possible fatalities worldwide, with range from 150,000 to 575,000.[10][11] In August 2010, the World Health Organization declared the swine flu pandemic officially over.[12][13]

Subsequent cases of swine flu were reported in India in 2015, with over 31,156 positive test cases and 1,841 deaths[14]

On 28 August ,2022 it was reported that three individuals had been infected with Swine influenza in India.[15]

Classification

Of the three genera of influenza viruses that cause human flu, two also cause influenza in pigs, with influenza A being common in pigs and influenza C being rare.[16]

Influenza B has not been reported in pigs. Within influenza A and influenza C, the strains found in pigs and humans are largely distinct, although because of reassortment there have been transfers of genes among strains crossing swine, avian, and human species boundaries.[17]

Influenza A

Swine influenza is caused by influenza A subtypes H1N1,[18] H1N2,[18] H2N3,[19] H3N1,[20] and H3N2.[18] In pigs, four influenza A virus subtypes (H1N1, H1N2, H3N2 and H7N9) are the most common strains worldwide.[21] In the United States, the H1N1 subtype was exclusively prevalent among swine populations before 1998; however, since late August 1998, H3N2 subtypes have been isolated from pigs. As of 2004, H3N2 virus isolates in US swine and turkey stocks were triple reassortants, containing genes from human (HA, NA, and PB1), swine (NS, NP, and M), and avian (PB2 and PA) lineages.[22] In August 2012, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed 145 human cases (113 in Indiana, 30 in Ohio, one in Hawaii and one in Illinois) of H3N2v since July 2012.[23] The death of a 61-year-old Madison County, Ohio woman is the first in the USA associated with a new swine flu strain. She contracted the illness after having contact with hogs at the Ross County Fair.[24]

Influenza C

Influenza viruses infect both humans and pigs, but do not infect birds.[25] Transmission between pigs and humans have occurred in the past.[26] For example, influenza C caused small outbreaks of a mild form of influenza amongst children in Japan[27] and California.[27] Because of its limited host range and the lack of genetic diversity in influenza C, this form of influenza does not cause pandemics in humans.[28]

Signs and symptoms

In pigs, a swine influenza infection produces fever, lethargy, sneezing, coughing, difficulty breathing and decreased appetite.[21] In some cases the infection can cause miscarriage. Although mortality is usually low (around 1–4%),[7] the virus can produce weight loss and poor growth, causing economic loss to farmers.[21] Infected pigs can lose up to 12 pounds of body weight over a three- to four-week period.[21] Swine have receptors to which both avian and mammalian influenza viruses are able to bind; this leads to the virus being able to evolve and mutate into different forms.[29] Influenza A is responsible for infecting swine, and was first identified in the summer of 1918.[29] Pigs have often been seen as "mixing vessels", which help to change and evolve strains of disease that are then passed on to other mammals, such as humans.[29]

Humans

In all, 50 cases are known to have occurred since the first report in medical literature in 1958, which have resulted in a total of six deaths.[30] Of these six people, one was pregnant, one had leukemia, one had Hodgkin's lymphoma and two were known to be previously healthy. One of these had unknown whereabouts.[30] Despite these apparently low numbers of infections, the true rate of infection may be higher, since most cases only cause a very mild disease, and will probably never be reported or diagnosed.[30]

According to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in humans the symptoms of the 2009 "swine flu" H1N1 virus are similar to influenza and influenza-like illness in general. Symptoms include fever, cough, sore throat, watery eyes, body aches, shortness of breath, headache, weight loss, chills, sneezing, runny nose, coughing, dizziness, abdominal pain, lack of appetite, and fatigue. The 2009 outbreak showed an increased percentage of patients reporting diarrhea and vomiting as well. The 2009 H1N1 virus is not zoonotic swine flu, as it is not transmitted from pigs to humans, but from person to person through airborne droplets.[2]

Because these symptoms are not specific to swine flu, a differential diagnosis of probable swine flu requires not only symptoms, but also a high likelihood of swine flu due to the person's recent and past medical history. For example, during the 2009 swine flu outbreak in the United States, the CDC advised physicians to "consider swine influenza infection in the differential diagnosis of patients with acute febrile respiratory illness who have either been in contact with persons with confirmed swine flu, or who were in one of the five U.S. states that have reported swine flu cases or in Mexico during the seven days preceding their illness onset."[31] A diagnosis of confirmed swine flu requires laboratory testing of a respiratory sample (a simple nose and throat swab).[31]

The most common cause of death is respiratory failure. Other causes of death are pneumonia (leading to sepsis),[32] high fever (leading to neurological problems), dehydration (from excessive vomiting and diarrhea), electrolyte imbalance and kidney failure.[33]

-

Main symptoms of swine flu in humans[34]

-

Description of the symptoms of swine flu and warning signs to look for that indicate the need for urgent medical attention. [35]

Virology

Transmission

Between pigs

Influenza is quite common in pigs, with about half of breeding pigs having been exposed to the virus in the US.[36] Antibodies to the virus are also common in pigs in other countries.[36]

The main route of transmission is through direct contact between infected and uninfected animals.[21] These close contacts are particularly common during animal transport. Intensive farming may also increase the risk of transmission, as the pigs are raised in very close proximity to each other.[37][38] The direct transfer of the virus probably occurs either by pigs touching noses, or through dried mucus. Airborne transmission through the aerosols produced by pigs coughing or sneezing are also an important means of infection.[21] The virus usually spreads quickly through a herd, infecting all the pigs within just a few days.[7] Transmission may also occur through wild animals, such as wild boar, which can spread the disease between farms.[39]

To humans

People who work with poultry and swine, especially those with intense exposures, are at increased risk of zoonotic infection with influenza virus endemic in these animals, and constitute a population of human hosts in which zoonosis and reassortment can co-occur.[40] Vaccination of these workers against influenza and surveillance for new influenza strains among this population may therefore be an important public health measure.[41] Transmission of influenza from swine to humans who work with swine was documented in a small surveillance study performed in 2004 at the University of Iowa.[42] This study, among others, forms the basis of a recommendation that people whose jobs involve handling poultry and swine be the focus of increased public health surveillance.[40] Other professions at particular risk of infection are veterinarians and meat processing workers, although the risk of infection for both of these groups is lower than that of farm workers.[43]

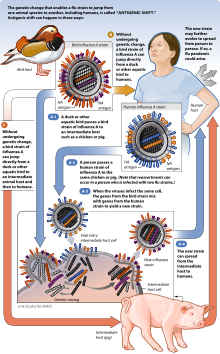

Interaction with avian H5N1 in pigs

Pigs are unusual as they can be infected with influenza strains that usually infect three different species: pigs, birds, and humans.[44] Pigs are a host where influenza viruses might exchange genes, producing new and dangerous strains.[44] Avian influenza virus H3N2 is endemic in pigs in China and has been detected in pigs in Vietnam, increasing fears of the emergence of new variant strains.[45] H3N2 evolved from H2N2 by antigenic shift.[46] In August 2004, researchers in China found H5N1 in pigs.[47]

These H5N1 infections may be quite common; in a survey of 10 apparently healthy pigs housed near poultry farms in West Java, where avian flu had broken out, five of the pig samples contained the H5N1 virus. The Indonesian government has since found similar results in the same region. Additional tests of 150 pigs outside the area were negative.[48][49]

Structure

In terms of the structure, H1N1 influenza virus is a orthomyxovirus. the virions are 80 to 120 nm in diameter, the genome has 8 different regions and encode eleven different proteins[2]

The influenza virion is roughly spherical, it is an enveloped virus; the outer layer is a lipid membrane which is taken from the host cell in which the virus multiplies. Inserted into the lipid membrane are "spikes", which are proteins—actually glycoproteins, because they consist of protein linked to sugars—known as HA (hemagglutinin) and NA (neuraminidase). These are the proteins that determine the subtype of influenza virus. The HA and NA are important in the immune response against the virus; antibodies against these spikes may protect against infection. The NA protein is the target of the antiviral drugs Relenza and Tamiflu. Also embedded in the lipid membrane is the M2 protein, which is the target of the antiviral adamantanes amantadine and rimantadine.[50][2][51][52]

Diagnosis

The CDC recommends real-time PCR as the method of choice for diagnosing H1N1.[4]

The oral or nasal fluid collection and RNA virus-preserving filter-paper card is commercially available.[53]

This method allows a specific diagnosis of novel influenza (H1N1) as opposed to seasonal influenza. Near-patient point-of-care tests are in development.[54]

Prevention

Prevention of swine influenza has three components: prevention in pigs, prevention of transmission to humans, and prevention of its spread among humans. Proper handwashing techniques can prevent the virus from spreading. Avoid touching the eyes, nose, or mouth. Stay away from others who display symptoms of the cold or flu and avoid contact with others when displaying symptoms.[55][2]

Swine

Methods of preventing the spread of influenza among swine include facility management, herd management, and vaccination (ATCvet code: QI09AA03 (WHO)). Because much of the illness and death associated with swine flu involves secondary infection by other pathogens, control strategies that rely on vaccination may be insufficient.[56]

Control of swine influenza by vaccination has become more difficult in recent decades, as the evolution of the virus has resulted in inconsistent responses to traditional vaccines. Standard commercial swine flu vaccines are effective in controlling the infection when the virus strains match enough to have significant cross-protection, and custom (autogenous) vaccines made from the specific viruses isolated are created and used in the more difficult cases.[57][58] Present vaccination strategies for SIV control and prevention in swine farms typically include the use of one of several bivalent SIV vaccines commercially available in the United States. Of the 97 recent H3N2 isolates examined, only 41 isolates had strong serologic cross-reactions with antiserum to three commercial SIV vaccines. Since the protective ability of influenza vaccines depends primarily on the closeness of the match between the vaccine virus and the epidemic virus, the presence of nonreactive H3N2 SIV variants suggests current commercial vaccines might not effectively protect pigs from infection with a majority of H3N2 viruses.[30][59] The United States Department of Agriculture researchers say while pig vaccination keeps pigs from getting sick, it does not block infection or shedding of the virus.[60]

Facility management includes using disinfectants and ambient temperature to control viruses in the environment. They are unlikely to survive outside living cells for more than two weeks, except in cold conditions, and are readily inactivated by disinfectants.[7] Herd management includes not adding pigs carrying influenza to herds that have not been exposed to the virus. The virus survives in healthy carrier pigs for up to three months and can be recovered from them between outbreaks. Carrier pigs are usually responsible for the introduction of SIV into previously uninfected herds and countries, so new animals should be quarantined.[36] After an outbreak, as immunity in exposed pigs wanes, new outbreaks of the same strain can occur.[7]

Humans

- Prevention of pig-to-human transmission

Swine can be infected by both avian and human flu strains of influenza, and therefore are hosts where the antigenic shifts can occur that create new influenza strains.[61][62]

The transmission from swine to humans is believed to occur mainly in swine farms, where farmers are in close contact with live pigs. Although strains of swine influenza are usually not able to infect humans, it may occasionally happen, so farmers and veterinarians are encouraged to use face masks when dealing with infected animals. The use of vaccines on swine to prevent their infection is a major method of limiting swine-to-human transmission. Risk factors that may contribute to the swine-to-human transmission include smoking and, especially, not wearing gloves when working with sick animals, thereby increasing the likelihood of subsequent hand-to-eye, hand-to-nose, or hand-to-mouth transmission.[63]

- Prevention of human-to-human transmission

Influenza spreads between humans when infected people cough or sneeze, then other people breathe in the virus or touch something with the virus on it and then touch their own face.[64] "Avoid touching your eyes, nose or mouth. Germs spread this way."[65] Swine flu cannot be spread by pork products, since the virus is not transmitted through food.[64] The swine flu in humans is most contagious during the first five days of the illness, although some people, most commonly children, can remain contagious for up to ten days. Diagnosis can be made by sending a specimen, collected during the first five days, for analysis.[66]

Recommendations to prevent the spread of the virus among humans include using standard infection control, which includes frequent washing of hands with soap and water or with alcohol-based hand sanitizers, especially after being out in public.[67] Chance of transmission is also reduced by disinfecting household surfaces, which can be done effectively with a diluted chlorine bleach solution.[68]

Experts agree hand-washing can help prevent viral infections, including ordinary and swine flu infections. Also, avoiding touching one's eyes, nose, or mouth with one's hands helps to prevent the flu.[65] Influenza can spread in coughs or sneezes, but an increasing body of evidence shows small droplets containing the virus can linger on tabletops, telephones, and other surfaces and be transferred via the fingers to the eyes, nose, or mouth. Alcohol-based gel or foam hand sanitizers work well to destroy viruses and bacteria. Anyone with flu-like symptoms, such as a sudden fever, cough, or muscle aches, should stay away from work or public transportation and should contact a doctor for advice.[69]

Social distancing, another tactic, is staying away from other people who might be infected, and can include avoiding large gatherings, spreading out a little at work, or perhaps staying home and lying low if an infection is spreading in a community. Public health and other responsible authorities have action plans which may request or require social distancing actions, depending on the severity of the outbreak.[70][71]

-

Thermal scanning of passengers

-

Thermal imaging camera and screen, photographed in an airport terminal in Greece – thermal imaging can detect elevated body temperature, one of the signs of the virus H1N1 (swine influenza).

Vaccination

Vaccines are available for different kinds of swine flu. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the new swine flu vaccine for use in the United States on September 15, 2009.[5] Studies by the National Institutes of Health show a single dose creates enough antibodies to protect against the virus within about 10 days.[72]

In the aftermath of the 2009 pandemic, several studies were conducted to see who received influenza vaccines. These studies show that whites are much more likely to be vaccinated for seasonal influenza and for the H1N1 strain than African Americans [73]

This could be due to several factors. Historically, there has been mistrust of vaccines and of the medical community from African Americans. Many African Americans do not believe vaccines or doctors to be effective. This mistrust stems from the exploitation of the African American communities during studies like the Tuskegee study. Additionally, vaccines are typically administered in clinics, hospitals, or doctor's offices; many people of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to receive vaccinations because they do not have health insurance.[74][75]

Surveillance

Although there is no formal national surveillance system in the United States to determine what viruses are circulating in pigs,[76] an informal surveillance network in the United States is part of a world surveillance network.[77]

Treatment

Swine

As swine influenza is rarely fatal to pigs, little treatment beyond rest and supportive care is required.[36] Instead, veterinary efforts are focused on preventing the spread of the virus throughout the farm or to other farms.[21] Vaccination and animal management techniques are most important in these efforts. Antibiotics are also used to treat the disease, which, although they have no effect against the influenza virus, do help prevent bacterial pneumonia and other secondary infections in influenza-weakened herds.[36]

In Europe the avian-like H1N1 and the human-like H3N2 and H1N2 are the most common influenza subtypes in swine, of which avian-like H1N1 is the most frequent. Since 2009 another subtype, pdmH1N1(2009), emerged globally and also in European pig population. The prevalence varies from country to country but all of the subtypes are continuously circulating in swine herds.[78] In the EU region whole-virus vaccines are available which are inactivated and adjuvanted. Vaccination of sows is common practice and reveals also a benefit to young pigs by prolonging the maternally level of antibodies. Several commercial vaccines are available including a trivalent one being used in sow vaccination and a vaccine against pdmH1N1(2009).[79]

Humans

If a person becomes sick with swine flu, antiviral drugs can make the illness milder and make the patient feel better faster. They may also prevent serious flu complications. For treatment, antiviral drugs work best if started soon after getting sick (within two days of symptoms). Beside antivirals, supportive care at home or in a hospital focuses on controlling fevers, relieving pain and maintaining fluid balance, as well as identifying and treating any secondary infections or other medical problems. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of oseltamivir (Tamiflu) or zanamivir (Relenza) for the treatment and/or prevention of infection with swine influenza viruses; however, the majority of people infected with the virus make a full recovery without requiring medical attention or antiviral drugs.[6] The virus isolated in the 2009 outbreak have been found resistant to amantadine and rimantadine.[80]

History

Pandemics

Swine influenza was first proposed to be a disease related to human flu during the 1918 flu pandemic, when pigs became ill at the same time as humans.[81] The first identification of an influenza virus as a cause of disease in pigs occurred about ten years later, in 1930.[82] For the following 60 years, swine influenza strains were almost exclusively H1N1. Then, between 1997 and 2002, new strains of three different subtypes and five different genotypes emerged as causes of influenza among pigs in North America. In 1997–1998, H3N2 strains emerged. These strains, which include genes derived by reassortment from human, swine and avian viruses, have become a major cause of swine influenza in North America. Reassortment between H1N1 and H3N2 produced H1N2. In 1999 in Canada, a strain of H4N6 crossed the species barrier from birds to pigs, but was contained on a single farm.[82]

The H1N1 form of swine flu is one of the descendants of the strain that caused the 1918 flu pandemic.[83][84] As well as persisting in pigs, the descendants of the 1918 virus have also circulated in humans through the 20th century, contributing to the normal seasonal epidemics of influenza.[84] However, direct transmission from pigs to humans is rare, with only 12 recorded cases in the U.S. since 2005.[85] Nevertheless, the retention of influenza strains in pigs after these strains have disappeared from the human population might make pigs a reservoir where influenza viruses could persist, later emerging to reinfect humans once human immunity to these strains has waned.[86]

Swine flu has been reported numerous times as a zoonosis in humans, usually with limited distribution, rarely with a widespread distribution. Outbreaks in swine are common and cause significant economic losses in industry, primarily by causing stunting and extended time to market. For example, this disease costs the British meat industry about £65 million every year.[87]

1918

The 1918 flu pandemic in humans was associated with H1N1 and influenza appearing in pigs;[84] this may reflect a zoonosis either from swine to humans, or from humans to swine. Although it is not certain in which direction the virus was transferred, some evidence suggests, in this case, pigs caught the disease from humans.[81] For instance, swine influenza was only noted as a new disease of pigs in 1918, after the first large outbreaks of influenza amongst people.[81] Although a recent phylogenetic analysis of more recent strains of influenza in humans, birds, animals, and many others, including swine, suggests the 1918 outbreak in humans followed a reassortment event within a mammal,[88] the exact origin of the 1918 strain remains elusive.[89] It is estimated that anywhere from 50 to 100 million people were killed worldwide.[84][90]

U.S. 2009

The swine flu was initially seen in the US in April 2009, where the strain of the particular virus was a mixture from 3 types of strains.[91]

Six of the genes are very similar to the H1N2 influenza virus that was found in pigs around 2000.[91]

Outbreaks

1976 U.S.

On February 5, 1976, a United States army recruit at Fort Dix said he felt tired and weak. He died the next day, and four of his fellow soldiers were later hospitalized. Two weeks after his death, health officials announced the cause of death was a new strain of swine flu. The strain, a variant of H1N1, is known as A/New Jersey/1976 (H1N1). It was detected only from January 19 to February 9 and did not spread beyond Fort Dix.[92]

This new strain appeared to be closely related to the strain involved in the 1918 flu pandemic. Moreover, the ensuing increased surveillance uncovered another strain in circulation in the U.S.: A/Victoria/75 (H3N2), which spread simultaneously, also caused illness, and persisted until March.[92] Alarmed public health officials decided action must be taken to head off another major pandemic, and urged President Gerald Ford that every person in the U.S. be vaccinated for the disease.[93]

The vaccination program was plagued by delays and public relations problems.[94] On October 1, 1976, immunizations began, and three senior citizens died soon after receiving their injections. This resulted in a media outcry that linked these deaths to the immunizations, despite the lack of any proof the vaccine was the cause. According to science writer Patrick Di Justo, however, by the time the truth was known—that the deaths were not proven to be related to the vaccine—it was too late. "The government had long feared mass panic about swine flu—now they feared mass panic about the swine flu vaccinations." This became a strong setback to the program.[95]

There were reports of Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS), a paralyzing neuromuscular disorder, affecting some people who had received swine flu immunizations. Although whether a link exists is still not clear, this syndrome may be a side effect of influenza vaccines. As a result, Di Justo writes, "the public refused to trust a government-operated health program that killed old people and crippled young people." In total, 48,161,019 Americans, or just over 22% of the population, had been immunized by the time the National Influenza Immunization Program was effectively halted on December 16, 1976.[96] [97]

Overall, there were 1098 cases of GBS recorded nationwide by CDC surveillance, 532 of which occurred after vaccination and 543 before vaccination.[98] About one to two cases per 100,000 people of GBS occur every year, whether or not people have been vaccinated.[99] The vaccination program seems to have increased this normal risk of developing GBS by about to one extra case per 100,000 vaccinations.[99]

Recompensation charges were filed for over 4,000 cases of severe vaccination damage, including 25 deaths, totaling US$3.5 billion, by 1979.[100] The CDC stated most studies on modern influenza vaccines have seen no link with GBS,[99][101][102] Although one review gives an incidence of about one case per million vaccinations,[103] a large study in China, reported in the New England Journal of Medicine, covering close to 100 million doses of H1N1 flu vaccine, found only 11 cases of GBS, which is lower than the normal rate of the disease in China: "The risk-benefit ratio, which is what vaccines and everything in medicine is about, is overwhelmingly in favor of vaccination."[104]

1988 U.S.

In September 1988, a swine flu virus killed one woman and infected others. A 32-year-old woman, Barbara Ann Wieners, was eight months pregnant when she and her husband, Ed, became ill after visiting the hog barn at a county fair in Walworth County, Wisconsin. Barbara died eight days later, after developing pneumonia.[105] The only pathogen identified was an H1N1 strain of swine influenza virus.[106]

Influenza-like illness (ILI) was reportedly widespread among the pigs exhibited at the fair. Of the 25 swine exhibitors aged 9 to 19 at the fair, 19 tested positive for antibodies to SIV, but no serious illnesses were seen. The virus was able to spread between people, since one to three health care personnel who had cared for the pregnant woman developed mild, influenza-like illnesses, and antibody tests suggested they had been infected with swine flu, but there was no community outbreak.[107][108]

In 1998, swine flu was found in pigs in four U.S. states. Within a year, it had spread through pig populations across the United States. Scientists found this virus had originated in pigs as a recombinant form of flu strains from birds and humans. This outbreak confirmed that pigs can serve as a crucible where novel influenza viruses emerge as a result of the reassortment of genes from different strains.[7][109] Genetic components of these 1998 triple-hybrid strains would later form six out of the eight viral gene segments in the 2009 flu outbreak.[110][111][112]

2007 Philippines

On August 20, 2007, Department of Agriculture officers investigated the outbreak of swine flu in Nueva Ecija and central Luzon, Philippines. The mortality rate is less than 10% for swine flu, unless there are complications like hog cholera. On July 27, 2007, the Philippine National Meat Inspection Service (NMIS) raised a hog cholera "red alert" warning over Metro Manila and five regions of Luzon after the disease spread to backyard pig farms in Bulacan and Pampanga, even if they tested negative for the swine flu virus.[113][114]

2009 Northern Ireland

Since November 2009, 14 deaths as a result of swine flu in Northern Ireland have been reported. The majority of the deceased were reported to have pre-existing health conditions which had lowered their immunity. This closely corresponds to the 19 patients who had died in the year prior due to swine flu, where 18 of the 19 were determined to have lowered immune systems. Because of this, many mothers who have just given birth are strongly encouraged to get a flu shot because their immune systems are vulnerable. Also, studies have shown that people between the ages of 15 and 44 have the highest rate of infection. Although most people now recover, having any conditions that lower one's immune system increases the risk of having the flu become potentially lethal. In Northern Ireland now, approximately 56% of all people under 65 who are entitled to the vaccine have gotten the shot, and the outbreak is said to be under control.[115]

2015 and 2019 India

Swine flu outbreaks were reported in India in late 2014 and early 2015. As of March 19, 2015 the disease has affected 31,151 people and claimed over 1,841 lives.[116][117] The largest number of reported cases and deaths due to the disease occurred in the western part of India including states like Delhi, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Gujarat Andhra Pradesh Researchers of MIT have claimed that the swine flu has mutated in India to a more virulent version with changes in Hemagglutinin protein,[118] contradicting earlier research by Indian researchers.[119]

There was another outbreak in India in 2017. The states of Maharashtra and Gujarat were the worst affected.[120] Gujarat high court has given Gujarat government instructions to control deaths by swine flu.[121] 1,090 people died of swine flu in India in 2019 until August 31, 2019.[122]

2015 Nepal

Swine flu outbreaks were reported in Nepal in the spring of 2015. Up to April 21, 2015, the disease had claimed 26 lives in the most severely affected district, Jajarkot in Northwest Nepal.[123] Cases were also detected in the districts of Kathmandu, Morang, Kaski, and Chitwan.[124] As of 22 April 2015 the Nepal Ministry of Health reported that 2,498 people had been treated in Jajarkot, of whom 552 were believed to have swine flu, and acknowledged that the government's response had been inadequate.[125]

2016 Pakistan

Seven cases of swine flu were reported in Punjab province of Pakistan, mainly in the city of Multan, in January 2017. Cases of swine flu were also reported in Lahore and Faisalabad.[126]

2017 Maldives

As of March 16, 2017, over a hundred confirmed cases of swine flu and at least six deaths were reported in the Maldivian capital of Malé and some other islands. Makeshift flu clinics were opened in Malé.[127] Schools in the capital were closed, prison visitations suspended, several events cancelled, and all non-essential travel to other islands outside the capital was advised against by the HPA. An influenza vaccination program focusing on pregnant women was initiated thereafter.[128]

2020 G4 EA H1N1 publication

G4 EA H1N1, also known as the G4 swine flu virus (G4) is a swine influenza virus strain discovered in China.[129] The virus is a variant genotype 4 (G4) Eurasian avian-like (EA) H1N1 virus that mainly affects pigs, but there is some evidence of it infecting people.[129] A peer-reviewed paper from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) stated that "G4 EA H1N1 viruses possess all the essential hallmarks of being highly adapted to infect humans ... Controlling the prevailing G4 EA H1N1 viruses in pigs and close monitoring of swine working populations should be promptly implemented."[130]

Michael Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization (WHO) Health Emergencies Program, stated in July 2020 that this strain of influenza virus was not new and had been under surveillance since 2011.[131] Almost 30,000 swine had been monitored via nasal swabs between 2011 and 2018.[130] While other variants of the virus have appeared and diminished, the study claimed the G4 variant has sharply increased since 2016 to become the predominant strain.[130][132] The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs rebutted the study, saying that the media had interpreted the study "in an exaggerated and nonfactual way" and that the number of pigs sampled was too small to demonstrate G4 had become the dominant strain.[133]

Between 2016 and 2018, a serum surveillance program screened 338 swine production workers in China for exposure (presence of antibodies) to G4 EA H1N1 and found 35 (10.4%) positive.[130] Among another 230 people screened who did not work in the swine industry, 10 (4.4%) were serum positive for antibodies indicating exposure.[129][130] Two cases of infection caused by the G4 variant have been documented as of July 2020, with no confirmed cases of human-to-human transmission.[129]

Health officials (including Anthony Fauci) say the virus should be monitored, particularly among those in close contact with pigs, but it is not an immediate threat.[134][135] There are no reported cases or evidence of the virus outside of China as of July 2020.[135]

H1N1 virus pandemic history

A 2008 study discussed the evolutionary origin of the flu strain of swine origin (S-OIV).[136]

According to this study, the phylogenetic origin of the flu virus that caused the 2009 pandemics can be traced before 1918. Around 1918, the ancestral virus, of avian origin, crossed the species boundaries and infected humans as human H1N1. The same phenomenon took place soon after in America, where the human virus infected pigs; it led to the emergence of the H1N1 swine strain, which later became known as swine flu.[136] Genetic coding of H1N1 shows it is a combination of segments of four influenza viruses forming a novel strain:[2]

- North American Swine (30.6%) – pig origin

- North American Avian (34.4%) – bird origin

- Human influenza strain (17.5%)

- Eurasian swine (17.5%) – Pig origin

Quadruple genetic re-assortment coinfection with influenza viruses from diverse animal species.[2]

Due to coinfection, the viruses are able to interact, mutate, and form a new strain to which host has variable immunity.New events of reassortment were not reported until 1968, when the avian strain H1N1 infected humans again; this time the virus met the strain H2N2, and the reassortment originated the strain H3N2. This strain has remained as a stable flu strain until now[137].

The critical moment for the 2009 outbreak was between 1990 and 1993. A triple reassortment event in a pig host of North American H1N1 swine virus, the human H3N2 virus and avian H1N1 virus generated the swine H1N2 strain. In 2009, when the virus H1N2 co-infected a human host at the same time as the Euroasiatic H1N1 swine strain a new human H1N1 strain emerged, which caused the 2009 pandemic.[138][139]

The swine flu spreads very rapidly worldwide due to its high human-to-human transmission rate and due to the frequency of air travel.[140]

See also

References

- ↑ International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. "The Universal Virus Database, version 4: Influenza A". Archived from the original on January 13, 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Jilani, Talha N.; Jamil, Radia T.; Siddiqui, Abdul H. (2022). "H1N1 Influenza". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Archived from the original on 2020-03-12. Retrieved 2022-08-31.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Chandra, Suresh; Bisht, Neelam (2010-03-01). "Swine Influenza". Apollo Medicine. 7 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1016/S0976-0016(12)60003-9. ISSN 0976-0016. Archived from the original on 2022-08-29. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "CDC H1N1 Flu | Interim Guidance on Specimen Collection, Processing, and Testing for Patients with Suspected Novel Influenza A (H1N1) (Swine Flu) Virus Infection". Cdc.gov. 2009-05-13. Archived from the original on 2009-05-02. Retrieved 2011-05-22.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "FDA Approves Vaccines for 2009 H1N1 Influenza Virus". FDA. Archived from the original on 2009-10-15. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "WHO | Pandemic (H1N1) 2009: Frequently asked questions". Archived from the original on 2009-04-29. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Swine influenza. The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2008. ISBN 978-1-4421-6742-1. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Zoonotic influenza". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 29 May 2022. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ↑ Haque, N.; Bari, M. S.; Bilkis, L.; Hossain, M. A.; Islam, M. A.; Hoque, M. M.; Haque, N.; Haque, S.; Ahmed, S.; Mirza, R.; Sumona, A. A.; Ahmed, M. U.; Ara, A. (January 2010). "Swine flu: a new emerging disease". Mymensingh medical journal: MMJ. 19 (1): 144–149. ISSN 1022-4742. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ↑ "CDC estimate of global H1N1 pandemic deaths: 284,000". CDC. CDC. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ "First Global Estimates of 2009 H1N1 Pandemic Mortality Released by CDC-Led Collaboration". CDC. CDC. 20 November 2019. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ↑ "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009". Archived from the original on April 28, 2009.

- ↑ "Swine Flu". National Health Portal of India. Archived from the original on 2022-08-16. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ Alhazmi, Mohammed I (30 April 2015). "Molecular docking of selected phytocompounds with H1N1 proteins". Bioinformation. 11 (4): 196–202. doi:10.6026/97320630011196. Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2022.

- ↑ Desk, India com News. "Jharkhand: 3 Tested Positive For Swine Flu in Ranchi Hospital, Had Symptoms Like COVID-19". www.india.com. Archived from the original on 28 August 2022. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ↑ Heinen PP (15 September 2003). "Swine influenza: a zoonosis". Veterinary Sciences Tomorrow. ISSN 1569-0830. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009.

Influenza B and C viruses are almost exclusively isolated from man, although influenza C virus has also been isolated from pigs and influenza B has recently been isolated from seals.

- ↑ Dandagi, GirishL; Byahatti, SujataM (2011). "An insight into the swine-influenza A (H1N1) virus infection in humans". Lung India. 28 (1): 34. doi:10.4103/0970-2113.76299. Archived from the original on 10 May 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Swine Influenza". Swine Diseases (Chest). Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine. Archived from the original on 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ Ma W, Vincent AL, Gramer MR, et al. (December 2007). "Identification of H2N3 influenza A viruses from swine in the United States". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (52): 20949–54. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10420949M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710286104. PMC 2409247. PMID 18093945.

- ↑ Shin JY, Song MS, Lee EH, et al. (November 2006). "Isolation and Characterization of Novel H3N1 Swine Influenza Viruses from Pigs with Respiratory Diseases in Korea". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 44 (11): 3923–27. doi:10.1128/JCM.00904-06. PMC 1698339. PMID 16928961.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 Kothalawala H, Toussaint MJ, Gruys E (June 2006). "An overview of swine influenza". Vet Q. 28 (2): 46–53. doi:10.1080/01652176.2006.9695207. PMID 16841566.

- ↑ Yassine HM, Al-Natour MQ, Lee CW, Saif YM (2007). "Interspecies and intraspecies transmission of triple reassortant H3N2 influenza A viruses". Virology Journal. 4: 129. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-4-129. PMC 2228287. PMID 18045494.

- ↑ "CDC confirms 145 cases of swine flu". FoxNews.com. 9 August 2012. Archived from the original on 10 August 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ Myers, Amanda Lee. "1st Death Linked to New Swine Flu is Ohioan, 61". AP. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2012.

- ↑ Bouvier NM, Palese P (September 2008). "The biology of influenza viruses". Vaccine. 26 Suppl 4 (Suppl 4): D49–53. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.039. PMC 3074182. PMID 19230160.

- ↑ Kimura H, Abiko C, Peng G, et al. (April 1997). "Interspecies transmission of influenza C virus between humans and pigs". Virus Research. 48 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1016/S0168-1702(96)01427-X. PMID 9140195.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Matsuzaki Y, Sugawara K, Mizuta K, et al. (February 2002). "Antigenic and Genetic Characterization of Influenza C Viruses Which Caused Two Outbreaks in Yamagata City, Japan, in 1996 and 1998". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40 (2): 422–29. doi:10.1128/JCM.40.2.422-429.2002. PMC 153379. PMID 11825952.

- ↑ Lynch JP, Walsh EE (April 2007). "Influenza: evolving strategies in treatment and prevention". Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 28 (2): 144–58. doi:10.1055/s-2007-976487. PMID 17458769.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Thacker, Eileen; Janke, Bruce (2008-02-15). "Swine Influenza Virus: Zoonotic Potential and Vaccination Strategies for the Control of Avian and Swine Influenzas". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 197 (Supplement 1): S19–S24. doi:10.1086/524988. ISSN 0022-1899. PMID 18269323.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Myers KP, Olsen CW, Gray GC (April 2007). "Cases of Swine Influenza in Humans: A Review of the Literature". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44 (8): 1084–88. doi:10.1086/512813. PMC 1973337. PMID 17366454.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (April 27, 2009). "CDC Health Update: Swine Influenza A (H1N1) Update: New Interim Recommendations and Guidance for Health Directors about Strategic National Stockpile Materiel". Health Alert Network. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ↑ "Study: Swine flu resembles feared 1918 flu". MSNBC. 2009-07-13. Archived from the original on 2009-07-15. Retrieved 2011-05-22.

- ↑ "Swine flu can damage kidneys, doctors find". Reuters. April 14, 2010. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2010.

- ↑ "Key Facts about Swine Influenza (Swine Flu)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on February 27, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2009.

- ↑ "Symptoms of H1N1 (Swine Flu)". YouTube. 2009-04-28. Archived from the original on 2021-11-17. Retrieved 2011-05-22.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 "Influenza Factsheet" (PDF). Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-03-23. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ Gilchrist MJ, Greko C, Wallinga DB, Beran GW, Riley DG, Thorne PS (February 2007). "The Potential Role of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations in Infectious Disease Epidemics and Antibiotic Resistance". Environmental Health Perspectives. 115 (2): 313–16. doi:10.1289/ehp.8837. PMC 1817683. PMID 17384785.

- ↑ Saenz RA, Hethcote HW, Gray GC (2006). "Confined Animal Feeding Operations as Amplifiers of Influenza". Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 6 (4): 338–46. doi:10.1089/vbz.2006.6.338. PMC 2042988. PMID 17187567.

- ↑ Vicente J, León-Vizcaíno L, Gortázar C, José Cubero M, González M, Martín-Atance P (July 2002). "Antibodies to selected viral and bacterial pathogens in European wild boars from southcentral Spain". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 38 (3): 649–52. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-38.3.649. hdl:10261/9789. PMID 12238391. S2CID 19073075.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Gray GC, Kayali G (April 2009). "Facing pandemic influenza threats: the importance of including poultry and swine workers in preparedness plans". Poultry Science. 88 (4): 880–84. doi:10.3382/ps.2008-00335. PMID 19276439.

- ↑ Gray GC, Trampel DW, Roth JA (May 2007). "Pandemic Influenza Planning: Shouldn't Swine and Poultry Workers Be Included?". Vaccine. 25 (22): 4376–81. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.036. PMC 1939697. PMID 17459539.

- ↑ Gray GC, McCarthy T, Capuano AW, Setterquist SF, Olsen CW, Alavanja MC (December 2007). "Swine Workers and Swine Influenza Virus Infections". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 13 (12): 1871–78. doi:10.3201/eid1312.061323. PMC 2876739. PMID 18258038.

- ↑ Myers KP, Olsen CW, Setterquist SF, et al. (January 2006). "Are Swine Workers in the United States at Increased Risk of Infection with Zoonotic Influenza Virus?". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 42 (1): 14–20. doi:10.1086/498977. PMC 1673212. PMID 16323086.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Thacker E, Janke B (February 2008). "Swine influenza virus: zoonotic potential and vaccination strategies for the control of avian and swine influenzas". J. Infect. Dis. 197 Suppl 1: S19–24. doi:10.1086/524988. PMID 18269323.

- ↑ Yu H, Hua RH, Zhang Q, et al. (March 2008). "Genetic Evolution of Swine Influenza A (H3N2) Viruses in China from 1970 to 2006". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 46 (3): 1067–75. doi:10.1128/JCM.01257-07. PMC 2268354. PMID 18199784.

- ↑ Lindstrom SE, Cox NJ, Klimov A (October 2004). "Genetic analysis of human H2N2 and early H3N2 influenza viruses, 1957–1972: evidence for genetic divergence and multiple reassortment events". Virology. 328 (1): 101–19. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2004.06.009. PMID 15380362.

- ↑ World Health Organization (28 October 2005). "H5N1 avian influenza: timeline" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesian pigs have avian flu virus; bird cases double in China". University of Minnesota: Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. 27 May 2005. Archived from the original on 2009-10-07. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ↑ Roos Robert, ed. (31 March 2009). "H5N1 virus may be adapting to pigs in Indonesia". University of Minnesota: Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy. Archived from the original on 2009-10-07. Retrieved 2009-04-26. report on pigs as carriers.

- ↑ Dadonaite, Bernadeta; Gilbertson, Brad; Knight, Michael L.; Trifkovic, Sanja; Rockman, Steven; Laederach, Alain; Brown, Lorena E.; Fodor, Ervin; Bauer, David L. V. (November 2019). "The structure of the influenza A virus genome". Nature Microbiology. 4 (11): 1781–1789. doi:10.1038/s41564-019-0513-7. ISSN 2058-5276. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- ↑ "Influenza Antiviral Medications: Clinician Summary". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 9 September 2022. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ "CDC H1N1 Flu | 2009 H1N1 and Seasonal Flu: What You Should Know About Flu Antiviral Drugs". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ "RNASound (TM) RNA Sampling Cards (25)". fortiusbio.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ "Micronics Acquires License to Biosearch Technologies' Nucleic Acid Assay Chemistries". Biosearchtech.com. 2009-10-28. Archived from the original on 2011-09-19. Retrieved 2011-05-22.

- ↑ "Prevent the Spread of Flu Between Pigs and People". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 August 2022. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2022.

- ↑ "Prevent the Spread of Flu Between Pigs and People". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 5 August 2022. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ↑ "Swine flu virus turns endemic". National Hog Farmer. 15 September 2007. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ↑ "Swine". Custom Vaccines. Novartis. Archived from the original on April 30, 2009.

- ↑ Gramer MR, Lee JH, Choi YK, Goyal SM, Joo HS (July 2007). "Serologic and genetic characterization of North American H3N2 swine influenza A viruses". Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research. 71 (3): 201–06. PMC 1899866. PMID 17695595.

- ↑ "Swine flu: The predictable pandemic?". 2009-04-29. Archived from the original on 2009-05-10. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ Glezen, W. Paul (1 January 2009). "CHAPTER 190 - INFLUENZA VIRUSES". Feigin and Cherry's Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (Sixth Edition). W.B. Saunders. pp. 2395–2413. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ↑ Kuntz-Simon, G.; Madec, F. (August 2009). "Genetic and antigenic evolution of swine influenza viruses in Europe and evaluation of their zoonotic potential". Zoonoses and Public Health. 56 (6–7): 310–325. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2009.01236.x. ISSN 1863-2378. Archived from the original on 27 March 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ↑ Ramirez A, Capuano AW, Wellman DA, Lesher KA, Setterquist SF, Gray GC (June 2006). "Preventing Zoonotic Influenza Virus Infection". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (6): 996–1000. doi:10.3201/eid1206.051576. PMC 1673213. PMID 16707061.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "Q & A: Key facts about swine influenza (swine flu) – Spread of Swine Flu". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-02-27. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 "CDC H1N1 Flu | H1N1 Flu and You". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2010-03-04. Retrieved 2011-05-22.

- ↑ "Q & A: Key facts about swine influenza (swine flu) – Diagnosis". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-02-27. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ↑ "Swine Influenza (Flu) Investigation". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2009-04-28. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ↑ "Chlorine Bleach: Helping to Manage the Flu Risk". Water Quality & Health Council. April 2009. Archived from the original on 2009-06-07. Retrieved 2009-05-12.

- ↑ "Self protection measures". LHC. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ↑ "Flu Pandemic Study Supports Social Distancing". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 22 May 2015. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ↑ Temte, Jonathan L. (1 June 2009). "Basic Rules of Influenza: How to Combat the H1N1 Influenza (Swine Flu) Virus". American Family Physician. 79 (11): 938–939. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ↑ "NIH studies on Swine flu vaccine". NIH. Archived from the original on October 13, 2009. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ↑ Uscher-Pines, Lori, Jurgen Maurer, and Katherine M. Harris. "Racial And Ethnic Disparities In Uptake And Location Of Vaccination For 2009–H1N1 And Seasonal Influenza." American Journal of Public Health 101.7 (2011) 1252–55. SocINDEX with Full Text. Web. 6 Dec. 2011.

- ↑ Burger, Andrew E.; Reither, Eric N.; Mamelund, Svenn-Erik; Lim, Sojung (February 2021). "Black-white disparities in 2009 H1N1 vaccination among adults in the United States: A cautionary tale for the COVID-19 pandemic". Vaccine. 39 (6): 943–951. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.069. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ↑ "Tuskegee Study - Timeline - CDC - NCHHSTP". www.cdc.gov. 3 May 2021. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ↑ Ginsberg M, Hopkins J; et al. (22 April 2009). "Swine influenza A (H1N1) infection in two children – Southern California, March–April 2009". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 58 (Dispatch) (1–3). Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ↑ Laura H. Kahn (2007-03-13). "Animals: The world's best (and cheapest) biosensors". Archived from the original on 2014-08-19. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ↑ Simon G; Larsen LE; et al. (2014). "European Surveillance Network for Influenza in Pigs: Surveillance Programs, Diagnostic Tools and Swine Influenza Virus Subtypes Identified in 14 European Countries from 2010 to 2013". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e115815. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k5815S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115815. PMC 4277368. PMID 25542013.

- ↑ Gracia JCM; Pearce DS; et al. (2020). "Influenza A Virus in Swine: Epidemiology, Challenges and Vaccination Strategies". Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 7: Article 647. doi:10.3389/fvets.2020.00647. PMC 7536279. PMID 33195504.

- ↑ "Antiviral Drugs and Swine Influenza". Centers for Disease Control. Archived from the original on 2009-04-29. Retrieved 2009-04-27.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats, Knobler SL, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon SM (2005). "1: The Story of Influenza". In Knobler S, Mack A, Mahmoud A, Lemon S (eds.). The Threat of Pandemic Influenza: Are We Ready? Workshop Summary. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. p. 75. doi:10.17226/11150. ISBN 978-0-309-09504-4. PMID 20669448. Archived from the original on 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Olsen CW (May 2002). "The emergence of novel swine influenza viruses in North America". Virus Research. 85 (2): 199–210. doi:10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00027-8. PMID 12034486.

- ↑ Boffey, Philip M. (5 September 1976). "Soft evidence and hard sell". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 84.3 Taubenberger JK, Morens DM (2006). "1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics". Emerg Infect Dis. 12 (1): 15–22. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050979. PMC 3291398. PMID 16494711.

- ↑ "U.S. pork groups urge hog farmers to reduce flu risk". Reuters. 26 April 2009. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ↑ Heinen, P. (2003). "Swine influenza: a zoonosis". Veterinary Sciences Tomorrow: 1–11. Archived from the original on 2009-05-06. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ↑ Kay RM, Done SH, Paton DJ (August 1994). "Effect of sequential porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome and swine influenza on the growth and performance of finishing pigs". Vet. Rec. 135 (9): 199–204. doi:10.1136/vr.135.9.199. PMID 7998380. S2CID 23678854.

- ↑ Vana G, Westover KM (June 2008). "Origin of the 1918 Spanish influenza virus: a comparative genomic analysis". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 47 (3): 1100–10. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2008.02.003. PMID 18353690.

- ↑ Antonovics J, Hood ME, Baker CH (April 2006). "Molecular virology: was the 1918 flu avian in origin?". Nature. 440 (7088): E9, discussion E9–10. Bibcode:2006Natur.440E...9A. doi:10.1038/nature04824. PMID 16641950. S2CID 4382489.

- ↑ Patterson KD, Pyle GF (1991). "The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 65 (1): 4–21. PMID 2021692.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Gibbs, Adrian J.; Armstrong, John S.; Downie, Jean C. (2009-01-01). "From where did the 2009 'swine-origin' influenza A virus (H1N1) emerge?". Virology Journal. 6: 207. doi:10.1186/1743-422X-6-207. ISSN 1743-422X. PMC 2787513. PMID 19930669.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Gaydos JC, Top FH, Hodder RA, Russell PK (January 2006). "Swine influenza a outbreak, Fort Dix, New Jersey, 1976". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (1): 23–28. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050965. PMC 3291397. PMID 16494712.

- ↑ Schmeck, Harold M. (March 25, 1976). "Ford Urges Flu Campaign To Inoculate Entire U.S." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2013-05-21. Retrieved 2017-02-13.

- ↑ Richard E. Neustadt and Harvey V. Fineberg. (1978). The Swine Flu Affair: Decision-Making on a Slippery Disease Archived 2009-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. National Academies Press.

- ↑ "The Last Great Swine Flu Epidemic" Archived 2009-11-03 at the Wayback Machine, Salon.com, April 28, 2009.

- ↑ Retailliau HF, Curtis AC, Storr G, Caesar G, Eddins DL, Hattwick MA (March 1980). "Illness after influenza vaccination reported through a nationwide surveillance system, 1976–1977". American Journal of Epidemiology. 111 (3): 270–78. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112896. PMID 7361749.

- ↑ "Historical National Population Estimates: July 1, 1900 to July 1, 1999". Washington D.C.: Population Division, U.S. Bureau of the Census. 2000-06-28. Archived from the original on 2009-10-13. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ↑ Schonberger LB, Bregman DJ, Sullivan-Bolyai JZ, et al. (August 1979). "Guillain–Barre syndrome following vaccination in the National Influenza Immunization Program, United States, 1976–1977". American Journal of Epidemiology. 110 (2): 105–23. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112795. PMID 463869.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 "General Questions and Answers on Guillain–Barré syndrome". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 14, 2009. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Swine Flu 1976 | Swine flu 'debacle' of 1976 is recalled – Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. 2009-04-27. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2011-08-17.

- ↑ Haber P, Sejvar J, Mikaeloff Y, DeStefano F (2009). "Vaccines and Guillain–Barré syndrome". Drug Safety. 32 (4): 309–23. doi:10.2165/00002018-200932040-00005. PMID 19388722. S2CID 33670594.

- ↑ Kaplan JE, Katona P, Hurwitz ES, Schonberger LB (August 1982). "Guillain–Barré syndrome in the United States, 1979–1980 and 1980–1981. Lack of an association with influenza vaccination". JAMA. 248 (6): 698–700. doi:10.1001/jama.248.6.698. PMID 7097920.

- ↑ Vellozzi C, Burwen DR, Dobardzic A, Ball R, Walton K, Haber P (March 2009). "Safety of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccines in adults: Background for pandemic influenza vaccine safety monitoring". Vaccine. 27 (15): 2114–20. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.01.125. PMID 19356614. Archived from the original on 2020-08-01. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ "Last Year's (2009) H1N1 Flu Vaccine Was Safe, Study Finds". Wunderground.com. 2011-02-02. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2011-05-22.

- ↑ McKinney WP, Volkert P, Kaufman J (January 1990). "Fatal swine influenza pneumonia during late pregnancy". Archives of Internal Medicine. 150 (1): 213–15. doi:10.1001/archinte.150.1.213. PMID 2153372.

- ↑ Kimura K, Adlakha A, Simon PM (March 1998). "Fatal case of swine influenza virus in an immunocompetent host". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 73 (3): 243–45. doi:10.4065/73.3.243. PMID 9511782.

- ↑ "Key Facts About Swine Flu". Cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-02-27. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

- ↑ Wells DL, Hopfensperger DJ, Arden NH, et al. (1991). "Swine influenza virus infections. Transmission from ill pigs to humans at a Wisconsin agricultural fair and subsequent probable person-to-person transmission". JAMA. 265 (4): 478–81. doi:10.1001/jama.265.4.478. PMID 1845913.

- ↑ Gangurde HH, Gulecha VS, Borkar VS, Mahajan MS, Khandare RA, Mundada AS (July 2011). "Swine Influenza A (H1N1 Virus): A pandemic disease". Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy. 2 (2): 110–124. doi:10.4103/0975-8453.86300. S2CID 71773062. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ↑ "CDC Confirms Ties to Virus First Discovered in U.S. Pig Factories". Archived from the original on August 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Video Segments 3,4,5 in Flu Factories: Tracing the Origins of the Swine Flu Pandemic". Archived from the original on October 13, 2009.

- ↑ "The Humane Society of the United States Video Portal". videos.humanesociety.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011.

- ↑ "DA probes reported swine flu 'outbreak' in N. Ecija". Gmanews.tv. Archived from the original on 2009-04-30. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ↑ "Gov't declares hog cholera alert in Luzon". Gmanews.tv. Archived from the original on 2009-04-29. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ↑ "New mothers urged to get swine flu vaccine". BBC News. 2011-01-10. Archived from the original on 2011-01-13. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ↑ PTI (March 19, 2015). "Swine flu toll inches towards 1,900". The Hindu. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Swine Flu Claims Over 1,700 Lives". NDTV.com. 12 March 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ↑ "The Swine Flu Virus Has Mutated Dangerously". Archived from the original on 2022-08-29. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ "Silver lining: No mutation of H1N1, says study". 2015-02-17. Archived from the original on 2022-08-29. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- ↑ "Maharashtra and Gujarat See Highest Number of Swine Flu Deaths". News18. Archived from the original on 2017-08-17. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- ↑ "Control swine flu deaths: Gujarat high court to government". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- ↑ "Swine flu kills over 1,000 Indians in 2017, worst outbreak since 2009-10". Moneycontrol. Archived from the original on 2017-08-26. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ↑ "One more dies of swine flu in Jajarkot". nepalaawaj.com. 21 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-01-30. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "Lab Test on three samples from Jajarkot confirms swine flu". infonepal.com. 15 April 2015. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "Swine flu outbreak kills 24 in Nepal". aa.com.tr. 22 April 2015. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- ↑ "Swine flu spreads across Punjab, 3 more patients identified in Multan, Pakistan". dunyanews.tv. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ↑ "Makeshift flu clinics swamped as H1N1 cases rise to 82 – Maldives". maldivesindependent.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ "Woman dies in second H1N1 fatality as cases rise above 100 – Maldives". maldivesindependent.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 129.2 129.3 "CDC takes action to prepare against 'G4' swine flu viruses in China with pandemic potential" (Press release). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 July 2020. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 130.2 130.3 130.4 Sun H, Xiao Y, Liu J, et al. (29 June 2020). "Prevalent Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza virus with 2009 pandemic viral genes facilitating human infection". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (29): 17204–17210. doi:10.1073/pnas.1921186117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7382246. PMID 32601207.

- ↑ "Recently publicized swine flu not new, under surveillance since 2011: WHO expert". Xinhuanet. 2 July 2020. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ↑ Cohen J (29 June 2020). "Swine flu strain with human pandemic potential increasingly found in pigs in China". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived from the original on 29 June 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ↑ "China says G4 swine flu virus not new; does not infect humans easily". Reuters. 4 July 2020. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ↑ Ries J (1 July 2020). "New swine flu discovered in China: why you don't need to worry too much yet". Healthline. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 Garcia de Jesus E (2 July 2020). "4 reasons not to worry about that 'new' swine flu in the news". Science News. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 Smith GJ, Vijaykrishna D, Bahl J, et al. (June 2009). "Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic". Nature. 459 (7250): 1122–25. Bibcode:2009Natur.459.1122S. doi:10.1038/nature08182. PMID 19516283.

- ↑ Komadina, Naomi; McVernon, Jodie; Hall, Robert; Leder, Karin (2014). "A Historical Perspective of Influenza A(H1N2) Virus". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (1): 6–12. doi:10.3201/eid2001.121848. ISSN 1080-6040. Archived from the original on 5 May 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ↑ "CDC H1N1 Flu | Origin of 2009 H1N1 Flu (Swine Flu)". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- ↑ Belagal, Praveen; Banavath, Hemanth Naick; Viswanath, Buddolla (1 January 2021). "Chapter 5 - Swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus: current status, threats, and challenges". Pandemic Outbreaks in the 21st Century. Academic Press. pp. 57–86. ISBN 978-0-323-85662-1. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ↑ Choffnes, Eileen R., Alison Mack, and David A. Relman. "The Domestic and International Impacts of the 2009–H1N1 Influenza a Pandemic: Global Challenges, Global Solutions : Workshop Summary". Washington, DC: National Academies, 2010. Print.

Further reading

- Alexander DJ (October 1982). "Ecological aspects of influenza A viruses in animals and their relationship to human influenza: a review". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 75 (10): 799–811. doi:10.1177/014107688207501010. PMC 1438138. PMID 6752410.

- Hampson AW, Mackenzie JS (November 2006). "The influenza viruses". The Medical Journal of Australia. 185 (10 Suppl): S39–43. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00705.x. PMID 17115950. S2CID 17069567. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- Lipatov AS, Govorkova EA, Webby RJ, et al. (September 2004). "Influenza: Emergence and Control". Journal of Virology. 78 (17): 8951–59. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.17.8951-8959.2004. PMC 506949. PMID 15308692.

- Van Reeth K (2007). "Avian and swine influenza viruses: our current understanding of the zoonotic risk" (PDF). Veterinary Research. 38 (2): 243–60. doi:10.1051/vetres:2006062. PMID 17257572. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-08-29. Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y (March 1992). "Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses". Microbiological Reviews. 56 (1): 152–79. doi:10.1128/MMBR.56.1.152-179.1992. PMC 372859. PMID 1579108.

- Winkler WG (October 1970). "Influenza in animals: its possible public health significance". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 6 (4): 239–42, discussion 247–48. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-6.4.239. PMID 16512120. S2CID 37771216.

External links

| Wikinews has news related to: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Swine influenza |

- Official swine flu advice and latest information from the UK National Health Service Archived 2007-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- 8 minute video answering common questions about the subject on fora.tv

- Swine flu charts and maps Numeric analysis and approximation of current active cases

- "Swine Influenza" disease card Archived 2022-03-08 at the Wayback Machine on World Organisation for Animal Health

- Worried about swine flu? Then you should be terrified about the regular flu. Archived 2009-04-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – Swine Flu Archived 2012-06-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy – Novel H1N1 influenza resource list Archived 2013-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Pandemic Flu US Government Site Archived 2009-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- World Health Organization (WHO): Swine influenza Archived 2011-01-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Medical Encyclopedia Medline Plus: Swine Flu Archived 2009-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Health-EU portal Archived 2013-09-22 at the Wayback Machine EU response to influenza

- European Commission – Public Health Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine EU coordination on Pandemic (H1N1) 2009

| Classification |

|---|

![Main symptoms of swine flu in humans[34]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a3/PD_Diagram_of_swine_flu_symptoms_EN.svg/233px-PD_Diagram_of_swine_flu_symptoms_EN.svg.png)