Fungal infection

| Fungal infection | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Mycoses,[1]fungal diseases[2] | |

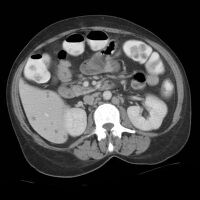

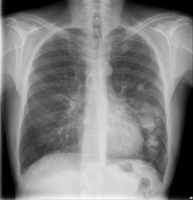

| Top: Superficial oral candida Bottom: Systemic aspergillosis pneumonia | |

| Specialty | Infectious Diseases[1][3] |

| Symptoms | Wide ranging[4] |

| Usual onset | Usually slowly progressive[5] |

| Types | Systemic, superficial, subcutaneous[4] |

| Causes | Pathogenic fungus: dermatophytes, yeasts, molds[6][7] |

| Risk factors | Immunodeficiency, cancer treatment, organ transplant,[6] tuberculosis, COVID-19 |

| Diagnostic method | Microscopy, biopsy, culture |

| Prevention | Hygiene |

| Treatment | Antifungal medication. Some require surgical debridement[4] |

| Frequency | Common[8] |

| Deaths | 1.7 million (2020)[9] |

Fungal infection, also known as mycosis, is disease caused by fungi.[3][10] Different types are traditionally divided according to the part of the body affected; superficial (in skin), subcutaneous (under skin), and systemic (other body parts).[4] Signs and symptoms range widely.[4] A fungal skin infection usually presents with a rash and includes common tinea of the skin, such as tinea of the body, groin, hands, feet and beard, and yeast infections such as pityriasis versicolor.[2][7] Fungal infection under skin include eumycetoma and chromoblastomycosis.[1][7] These may present with a lump and skin changes.[4] Systemic fungal infections are more serious, and often present with pneumonia, meningitis and deep tissue damage; they include cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, pneumocystis pneumonia, aspergillosis and mucormycosis.[2][4]

Fungal spores are usually found in the air and soil, but only cause infection in some people.[10] Infection can occur after spores are either breathed in, come into contact with skin or enter the body through the skin such as via a cut, wound or injection, or spread through blood.[4][10] Hence, a fungal infection usually begins in the skin or lungs, and then progresses slowly.[5] Although most fungi do not cause infection, fungal infection can occur in healthy people, but is more likely in a person with a weakened immune system, if taking medicines that suppress the immune system such as steroids, cancer treatments or medicines needed after organ transplant, in a condition that causes immunodeficiency such as HIV/AIDS, if there is a medical device such as an artificial joint or heart valve, or in someone who has a long stay in intensive care.[11][12] Taking antibiotics may allow a fungi normally present in the body to overgrow and cause infection.[5] Fungi that cause disease in people include yeasts, molds and fungi that are able to exist as both a mold and yeast.[4][6] The yeast Candida albicans can live in people without producing symptoms, and is able to cause both superficial mild candidiasis in healthy people, such as oral thrush or vaginal yeast infection, and severe systemic candidiasis in those who cannot fight infection themselves.[4] A fungal infection is rarely passed from person to person.[5]

Diagnosis is generally by clinical features and confirmed by culture and microscopical examination of a sample such as sputum, blood, or a sample from the lungs or other tissue by biopsy.[5] A blood test may be done to check for antibodies and antigens.[5] Medical imaging can help to evaluate the extent of disease.[6] Some superficial fungal infections of the skin can appear similar to eczema and lichen planus.[7] Treatment generally involves antifungal medicines, usually in the form of a cream, applied to skin, vagina or mouth.[5] More serious fungal infection may require medicines by mouth or injection.[13] Some require several months of treatment and surgically cutting out infected tissue.[4][5]

Worldwide, fungal infections affect more than one billion people every year.[8] An estimated 1.7 million deaths from fungal disease were reported in 2020.[9] Several, including sporotrichosis, chromoblastomycosis and eumycetoma are neglected.[14] A wide range of fungal infections occur in other animals, and some some can be transmitted from animals to people.[15]

Signs and symptoms

Most common mild fungal infections often present with a rash.[2] Fungal infections within the skin or under the skin may present with a lump and skin changes.[4] Less common deeper fungal infections may present with pneumonia like symptoms or meningitis.[2]

Classification

Fungal infections are traditionally divided into superficial, subcutaneous, or systemic, where infection is deep, more widespread and maybe involving internal body organs.[4] Superficial is sometimes separated into "superficial", confined to outermost layer of skin, and "cutaneous", also involving skin attachments; hair, nails.[8] They can affect the nails, vagina, skin and mouth.[16] Some types such as blastomycosis, cryptococcus, coccidioidomycosis and histoplasmosis, affect people who live or visit certain parts of the world.[16] Others such as aspergillosis, pneumocystis pneumonia, candidiasis, mucormycosis and talaromycosis, tend to affect people who are unable to fight infection themselves.[16]

- 1F20 Aspergillosis

- 1F21 Basidiobolomycosis

- 1F22 Blastomycosis

- 1F23 Candidosis

- 1F24 Chromoblastomycosis

- 1F25 Coccidioidomycosis

- 1F26 Conidiobolomycosis

- 1F27 Cryptococcosis

- 1F28 Dermatophytosis

- 1F29 Eumycetoma

- 1F2A Histoplasmosis

- 1F2B Lobomycosis

- 1F2C Mucormycosis

- 1F2D Non-dermatophyte superficial dermatomycoses

- 1F2F Phaeohyphomycosis

- 1F2G Pneumocystosis

- 1F2H Scedosporiosis

- 1F2J Sporotrichosis

- 1F2K Talaromycosis

- 1F2L Emmonsiosis

Superficial and skin

Fungal infections in the skin include candidiasis, common tinea of the skin, such as tinea of the body, groin, hands, feet and beard, and malassezia infections such as pityriasis versicolor and seborrheic dermatitis.[4][7]

-

Tinea pedis (feet)

-

Tinea corporis (localised on body)

-

Tinea cruris (groin)

-

Tinea manuum (hands)

-

Tinea capitis (head)

-

Tinea barbae (beard)

Subcutaneous

Subcutaneous fungal infections include sporotrichosis, chromoblastomycosis, and eumycetoma.[4]

Systemic

Systemic fungal infections include histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, mucormycosis, aspergillosis, pneumocystis pneumonia and systemic candidiasis.[4] Opportunistic systemic fungal infections include candidiasis, cryptococcosis and aspergillosis.[4]

-

Chest X-ray: Angioinvasive aspergillosis

-

Chest X-ray of lungs affected by cryptococcosis

-

Chest X-ray of lungs affected by histoplasmosis

-

X-ray of cyst in pneumocystis pneumonia[17]

Other

Fungal infections might not always conform strictly to the three divisions of superficial, subcutaneous and systemic.[4] Some superficial fungal infections can cause systemic infections in people who are immunocompromised.[4] Some subcutaneous fungal infections can invade into deeper structures, resulting in systemic disease.[4] Candida albicans can live in people without producing symptoms, and is able to cause both mild candidiasis in healthy people and severe invasive candidiasis in those who cannot fight infection themselves.[4][7]

-

Coccidioidomycosis

-

Histoplasmosis in skin

-

Aspergillosis of skin

-

Mucormycosis of skin of forehead

-

CT scan: Liver candidiasis - multiple small rounded foci in liver and spleen.

Causes

Fungal infections are caused by certain fungi; yeasts, molds and some fungi that can exist as both a mold and yeast.[4][6] They are generally everywhere and infection occurs after spores are either breathed in, come into contact with skin or enter the body through the skin such as via a cut, wound or injection.[4] Candida albicans is the most common cause of fungal infection in people, particularly as oral or vaginal thrush, often following taking antibiotics.[4]

Risk factors

Fungal infections are more likely in people with weak immune systems.[12] This includes people with illnesses such as HIV/AIDS, and people taking medicines such as steroids, immunosuppressive therapy or cancer treatments.[12] People with diabetes also tend to develop fungal infections.[18] Very old people, also, are groups at risk.[9] Other risk factors include having a medical device such as an artificial joint or heart valve, or having a long stay in intensive care.[12][5]

Individuals being treated with antibiotics are at higher risk of fungal infections.[19] Children whose immune systems are not functioning properly (such as children with cancer) are at risk of invasive fungal infections.[20]

COVID-19

During the COVID-19 pandemic some fungal infections have been associated with COVID-19.[21][22][23] Fungal infections can mimic COVID-19, occur at the same time as COVID-19 and more serious fungal infections can complicate COVID-19.[21] A fungal infection may occur after antibiotics for a bacterial infection which has occurred following COVID-19.[24] The most common serious fungal infections in people with COVID-19 include aspergillosis and invasive candidiasis.[25] COVID-19–associated mucormycosis is generally less common, but in 2021 was noted to be significantly more prevalent in India.[21][26]

Mechanism

Fungal infections occur after spores are either breathed in, come into contact with skin or enter the body through a wound.[4]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is generally by appearance, signs and symptoms.[6] Confirmation is by culture and microscopical examination of a sample such as a skin scraping, nail cutting, sputum, blood, urine, bone marrow, a sample of cerebrospinal fluid, or a sample from the lungs or other tissue by biopsy.[5][27] A blood test may be done to check for antibodies and antigens.[5] Medical imaging can help to evaluate the extent of disease.[6]

Differential diagnosis

Some tinea and candidiasis infections of the skin can appear similar to eczema and lichen planus.[7] Pityriasis versicolor can look like seborrheic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, pityriasis alba and vitiligo. [7]

Some fungal infections such as coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, and blastomycosis can present with fever, cough, and shortness of breath, thereby resembling COVID-19.[25]

Prevention

Keeping the skin clean and dry, as well as maintaining good hygiene, will help larger topical mycoses. Because fungal infections are contagious, it is important to wash after touching other people or animals. Sports clothing should also be washed after use.[citation needed]

Treatment

Treatment usually requires topical or systemic antifungal medicines.[13] Sometimes, infected tissue needs to be surgically cut out.[4]

Epidemiology

Worldwide, every year fungal infections affect more than one billion people.[8][9] An estimated 1.6 million deaths from fungal disease were reported in 2017,[28] and 1.7 million in 2020.[9] Fungal infection of skin is the most common type of infection worldwide,[29] and one of the most common causes of skin disease.[30]

According to the Global Action Fund for Fungal Infections, every year there are over 10 million cases of fungal asthma, around 3 million cases of long-term aspergillosis of lungs, 1 million cases of blindness due to fungal keratitis, more than 200,000 cases of meningitis due to cryptococcus, 700,000 cases of invasive candidiasis, 500,000 cases of pneumocystosis of lungs, 250,000 cases of invasive aspergillosis, and 100,000 cases of histoplasmosis.[31] They also constitute a significant cause of illness and death in children.[32]

History

In 500BC, an apparent account of ulcers in the mouth by Hippocrates may have been thrush.[33] The Hungarian microscopist based in Paris David Gruby first reported that human disease could be caused by fungi in the early 1840s.[33]

SARS 2003

During the 2003 SARS outbreak, fungal infections were reported in 14.8–33% of people affected by SARS, and it was the cause of death in 25–73.7% of people with SARS.[34]

Other animals

A wide range of fungal infections occur in other animals, and some some can be transmitted from animals to people, such as Microsporum canis from cats.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "25. Mycoses and Algal infections". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 438–465. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2023-07-01. Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Fungal Diseases Homepage | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 29 March 2021. Archived from the original on 29 May 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 Barlow, Gavin; Irving, Irving; moss, Peter J. (2020). "20. Infectious diseases". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 559–563. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-13.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 Revankar, Sanjay G. (April 2021). "Overview of Fungal Infections - Infections". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Willinger, Birgit (2019). "1. What is the target? Clinical mycology and diagnostics". In Elisabeth Presterl (ed.). Clinically Relevant Mycoses: A Practical Approach. Springer. pp. 3–19. ISBN 978-3-319-92299-7. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Kutzner, Heinz; Kempf, Werner; Feit, Josef; Sangueza, Omar (2021). "2. Fungal infections". Atlas of Clinical Dermatopathology: Infectious and Parasitic Dermatoses. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. p. 77-108. ISBN 978-1-119-64706-5. Archived from the original on 2021-06-10. Retrieved 2021-05-29.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Nakazato, Gerson; Alesandra, Audrey; Lonni, Stringhen Garcia; Panagio, Luciano Aparecido; de Camargo, Larissa Ciappina; Goncalves, Marcelly Chue; Reis, Guilherne Fonseca; Miranda-Sapla, Milena Menegazzo; Tomiotto-Pellissier, Fernanda; Kobayashi, Renata Katsuko Takayama (2020). "4. Applications of nanometals in cutaneous infections". In Rai, Mahendra (ed.). Nanotechnology in Skin, Soft Tissue, and Bone Infections. Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-35146-5. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-05-26.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Kainz, Katharina; Bauer, Maria A.; Madeo, Frank; Carmona-Gutierrez, Didac (1 June 2020). "Fungal infections in humans: the silent crisis". Microbial Cell. 7 (6): 143–145. doi:10.15698/mic2020.06.718. ISSN 2311-2638. PMID 32548176. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Richardson, Malcolm D.; Warnock, David W. (2012). "1. Introduction". Fungal Infection: Diagnosis and Management (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–7. ISBN 978-1-4051-7056-7. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ↑ Seagle, Emma E.; Williams, Samantha L.; Chiller, Tom L. (2021). "Recent trends in the epidemiology of fungal infections". In Ostrosky-Zeichner, Luis (ed.). Fungal Infections, An Issue of Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-0-323-81294-8. Archived from the original on 2021-09-03. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 "Fungal Infections | Fungal | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 29 January 2019. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Graininger, Wolfgang; Diab-Elschahawi, Magda; Presterl, Elisabeth (2019). "3. Antifungal agents". In Elisabeth Presterl (ed.). Clinically Relevant Mycoses: A Practical Approach. Springer. pp. 31–44. ISBN 978-3-319-92299-7. Archived from the original on 2021-06-02. Retrieved 2021-05-31.

- ↑ Queiroz-Telles, Flavio; Fahal, Ahmed Hassan; Falci, Diego R.; Caceres, Diego H.; Chiller, Tom; Pasqualotto, Alessandro C. (1 November 2017). "Neglected endemic mycoses". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 17 (11): e367–e377. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30306-7. ISSN 1473-3099. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Seyedmousavi, Seyedmojtaba; Bosco, Sandra de M G; de Hoog, Sybren; Ebel, Frank; Elad, Daniel; Gomes, Renata R; Jacobsen, Ilse D; Jensen, Henrik E; Martel, An; Mignon, Bernard; Pasmans, Frank; Piecková, Elena; Rodrigues, Anderson Messias; Singh, Karuna; Vicente, Vania A; Wibbelt, Gudrun; Wiederhold, Nathan P; Guillot, Jacques (April 2018). "Fungal infections in animals: a patchwork of different situations". Medical Mycology. 56 (Suppl 1): S165–S187. doi:10.1093/mmy/myx104. ISSN 1369-3786. PMID 29538732. Archived from the original on 2020-01-08. Retrieved 2021-08-07.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "Types of Fungal Diseases | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 27 June 2019. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ↑ Khan, AliNawaz; Allen, CarolynM; AL-Jahdali, HamdanH; Irion, KlausL; Al Ghanem, Sarah; Gouda, Alaa (2010). "Imaging lung manifestations of HIV/AIDS". Annals of Thoracic Medicine. 5 (4): 201–16. doi:10.4103/1817-1737.69106. ISSN 1817-1737. PMC 2954374. PMID 20981180. Creative Commons Attribution License

- ↑ "Thrush in Men". NHS. Archived from the original on 2013-07-03. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ↑ Britt, L. D.; Peitzman, Andrew; Barie, Phillip; Jurkovich, Gregory (2012). Acute Care Surgery. p. 186. ISBN 9781451153934. Archived from the original on 2021-04-13. Retrieved 2021-05-20.

- ↑ Blyth, Christopher C; Hale, Katherine; Palasanthiran, Pamela; O'Brien, Tracey; Bennett, Michael H (2010-02-17). "Antifungal therapy in infants and children with proven, probable or suspected invasive fungal infections". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD006343. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006343.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 20166083.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 "Fungal Diseases and COVID-19 | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2021-06-07. Archived from the original on 2021-06-21. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ↑ Hoenigl, Martin; Talento, Alida Fe, eds. (2021). Fungal Infections Complicating COVID-19. MDPI. ISBN 978-3-0365-0554-1. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-07-10.

- ↑ Gangneux, J.-P.; Bougnoux, M.-E.; Dannaoui, E.; Cornet, M.; Zahar, J.R. (June 2020). "Invasive fungal diseases during COVID-19: We should be prepared". Journal De Mycologie Medicale. 30 (2): 100971. doi:10.1016/j.mycmed.2020.100971. ISSN 1156-5233. PMID 32307254. Archived from the original on 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2021-07-10.

- ↑ Saxena, Shailendra K. (2020). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapeutics. Singapore: Springer. p. 73. ISBN 978-981-15-4813-0. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-07-10.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "Fungal Diseases and COVID-19". www.cdc.gov. 7 June 2021. Archived from the original on 21 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ↑ Qu, Jie-Ming; Cao, Bin; Chen, Rong-Chang (2021). COVID-19: The Essentials of Prevention and Treatment. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-824003-8. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-07-10.

- ↑ "MedlinePlus: Medical Tests". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ↑ "Stop neglecting fungi". Nature Microbiology. 2 (8): 17120. 25 July 2017. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.120. ISSN 2058-5276. PMID 28741610.

- ↑ James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "15. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Elsevier. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ↑ Hay, Roderick J.; Johns, Nicole E.; Williams, Hywel C.; Bolliger, Ian W.; Dellavalle, Robert P.; Margolis, David J.; Marks, Robin; Naldi, Luigi; Weinstock, Martin A.; Wulf, Sarah K.; Michaud, Catherine; Murray, Christopher J.L.; Naghavi, Mohsen (Oct 28, 2013). "The Global Burden of Skin Disease in 2010: An Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact of Skin Conditions". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 134 (6): 1527–34. doi:10.1038/jid.2013.446. PMID 24166134.

- ↑ Rodrigues, Marcio L.; Nosanchuk, Joshua D. (20 February 2020). "Fungal diseases as neglected pathogens: A wake-up call to public health officials". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 14 (2): e0007964. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0007964. ISSN 1935-2735. PMID 32078635. Archived from the original on 21 June 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ↑ Sehgal, Mukul; Ladd, Hugh J.; Totapally, Balagangadhar (1 December 2020). "Trends in Epidemiology and Microbiology of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock in Children". Hospital Pediatrics. 10 (12): 1021–1030. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2020-0174. ISSN 2154-1663. PMID 33208389. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Homei, A.; Worboys, M. (11 November 2013). "1. Introduction". Fungal Disease in Britain and the United States 1850-2000: Mycoses and Modernity. Springer. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-333-71492-8. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ↑ Song, Ge; Liang, Guanzhao; Liu, Weida (31 July 2020). "Fungal Co-infections Associated with Global COVID-19 Pandemic: A Clinical and Diagnostic Perspective from China". Mycopathologia: 1–8. doi:10.1007/s11046-020-00462-9. ISSN 0301-486X. PMID 32737747. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

![X-ray of cyst in pneumocystis pneumonia[17]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f7/X-ray_of_cyst_in_pneumocystis_pneumonia_1.jpg/250px-X-ray_of_cyst_in_pneumocystis_pneumonia_1.jpg)