Tinea capitis

| Tinea capitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Herpes tonsurans,[1] ringworm of the hair,[1] ringworm of the scalp,[1] scalp ringworm,[2] tinea tonsurans[1] | |

| |

| Tinea capitis | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

| Symptoms | Scaly, red roundish patch on head, fragile broken hair, large lymph node, scarring[3] |

| Types | Tinea favosa[3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Seborrhoeic dermatitis, folliculitis[3] |

Tinea capitis, also known as ringworm of the scalp, is a type of fungal infection of the skin of the scalp.[2][3] The clinical presentation is typically single or multiple patches of hair loss, sometimes with a 'black dot' pattern (often with broken-off hairs), that may be accompanied by inflammation, scaling, pustules, and itching.[citation needed]

The disease is primarily caused by dermatophytes in the genera Trichophyton and Microsporum that invade the hair shaft. At least eight species of dermatophytes are associated with tinea capitis. Cases of Trichophyton infection predominate from Central America to the United States and in parts of Western Europe. Infections from Microsporum species are mainly in South America, Southern and Central Europe, Africa and the Middle East. The disease is infectious and can be transmitted by humans, animals, or objects that harbor the fungus. The fungus can also exist in a carrier state on the scalp, without clinical symptomatology.[citation needed]

Treatment of tinea capitis requires an oral antifungal agent; griseofulvin is the most commonly used drug, but other newer antimycotic drugs, such as terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole have started to gain acceptance.[citation needed]

Uncommon in adults, tinea capitis is predominantly seen in pre-pubertal children, more often boys than girls.[citation needed]

Signs and symptoms

It may appear as thickened, scaly, and sometimes boggy swellings, or as expanding raised red rings (ringworm). Common symptoms are severe itching of the scalp, dandruff, and bald patches where the fungus has rooted itself in the skin. It often presents identically to dandruff or seborrheic dermatitis. The highest incidence in the United States of America is in American boys of school age.[4]

Causes

Most are caused by caused by Trichophyton tonsurans, while T. violaceum.[5]

There are three type of tinea capitis, microsporosis, trichophytosis, and favus; these are based on the causative microorganism, and the nature of the symptoms. In microsporosis, the lesion is a small red papule around a hair shaft that later becomes scaly; eventually the hairs break off 1–3 mm above the scalp. This disease used to be caused primarily by Microsporum audouinii, but in Europe, M. canis is more frequently the causative fungus. The source of this fungus is typically sick cats and kittens; it may be spread through person to person contact, or by sharing contaminated brushes and combs. In the United States, Trichophytosis is usually caused by Trichophyton tonsurans, while T. violaceum is more common in Eastern Europe, Africa, and India. This fungus causes dry, non-inflammatory patches that tend to be angular in shape. When the hairs break off at the opening of the follicle, black dots remain. Favus is caused by T. schoenleinii, and is endemic in South Africa and the Middle East. It is characterized by a number of yellowish, circular, cup-shaped crusts (scutula) grouped in patches like a piece of honeycomb, each about the size of a split pea, with a hair projecting in the center. These increase in size and become crusted over, so that the characteristic lesion can only be seen around the edge of the scab.[6]

Pathophysiology

From the site of inoculation, the fungus grows down into the stratum corneum, where it invades keratin. Dermatophytes are unique in that they produce keratinase, which enables them to use keratin as a nutrient source. Infected hairs become brittle, and after three weeks, the clinical presentation of broken hairs is evident.[4]

There are three types of infection:

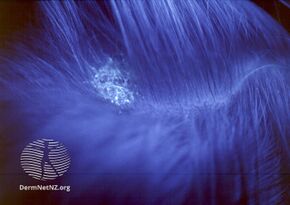

Ectothrix: Characterized by the growth of fungal spores (arthroconidia) on the exterior of the hair shaft. Infected hairs usually fluoresce greenish-yellow under a Wood lamp (blacklight). Associated with Microsporum canis, Microsporum gypseum, Trichophyton equinum, and Trichophyton verrucosum.

Endothrix: Similar to ectothrix, but characterized by arthroconidia restricted to the hair shaft, and restricted to anthropophilic bacteria. The cuticle of the hair remains intact and clinically this type does not have fluorescence. Associated with Trichophyton tonsurans and Trichophyton violaceum, which are anthropophilic.

Favus: Causes crusting on the surface of the skin, combined with hair loss. Associated with Trichophyton schoenleini.[4]

Diagnosis

Tinea capitis may be difficult to distinguish from other skin diseases that cause scaling, such as psoriasis and seborrhoeic dermatitis; the basis for the diagnosis is positive microscopic examination and microbial culture of epilated hairs.[7] Wood's lamp examination will reveal bright green to yellow-green fluorescence of hairs infected by M. canis, M. audouinii, M. rivalieri, and M. ferrugineum and a dull green or blue-white color of hairs infected by T. schoenleinii.[8] Individuals with M. canis infection trichoscopy will show characteristic small comma hairs.[9] Histopathology of scalp biopsy shows fungi sparsely distributed in the stratum corneum and hyphae extending down the hair follicle, placed on the surface of the hair shaft. These findings are occasionally associated with inflammatory tissue reaction in the local tissue.[10]

Treatment

The treatment of choice by dermatologists is a safe and inexpensive oral medication, griseofulvin, a secondary metabolite of the fungus Penicillium griseofulvin. This compound is fungistatic (inhibiting the growth or reproduction of fungi) and works by affecting the microtubular system of fungi, interfering with the mitotic spindle and cytoplasmic microtubules. The recommended pediatric dosage is 10 mg/kg/day for 6–8 weeks, although this may be increased to 20 mg/kg/d for those infected by T. tonsurans, or those who fail to respond to the initial 6 weeks of treatment.[11] Unlike other fungal skin infections that may be treated with topical therapies like creams applied directly to the afflicted area, griseofulvin must be taken orally to be effective; this allows the drug to penetrate the hair shaft where the fungus lives. The effective therapy rate of this treatment is generally high, in the range of 88–100%.[12] Other oral antifungal treatments for tinea capitis also frequently reported in the literature include terbinafine, itraconazole, and fluconazole; these drugs have the advantage of shorter treatment durations than griseofulvin.[13] A 2016 meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that terbinafine, itraconazole and fluconazole were at least equally effective as griseofulvin for children infected with Trichophyton, and terbinafine is more effective than griseofulvin for children with T. tonsurans infection.[14] However, concerns have been raised about the possibility of rare side effects like liver toxicity or interactions with other drugs; furthermore, the newer drug treatments tend to be more expensive than griseofulvin.[15]

On September 28, 2007, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration stated that Lamisil (Terbinafine hydrochloride, by Novartis AG) is a new treatment approved for use by children aged 4 years and older. The antifungal granules can be sprinkled on a child's food to treat the infection.[16] Lamisil carries hepatotoxic risk, and can cause a metallic taste in the mouth.

Epidemiology

Tinea capitis caused by species of Microsporum and Trichophyton is a contagious disease that is endemic in many countries. Affecting primarily pre-pubertal children between 6 and 10 years, it is more common in males than females; rarely does the disease persist past age sixteen.[17] Because spread is thought to occur through direct contact with afflicted individuals, large outbreaks have been known to occur in schools and other places where children are in close quarters; however, indirect spread through contamination with infected objects (fomites) may also be a factor in the spread of infection. In the US, tinea capitis is thought to occur in 3-8% of the pediatric population; up to one-third of households with contact with an infected person may harbor the disease without showing any symptoms.[18]

The fungal species responsible for causing tinea capitis vary according to the geographical region, and may also change over time. For example, Microsporum audouinii was the predominant etiological agent in North America and Europe until the 1950s, but now Trichophyton tonsurans is more common in the US, and becoming more common in Europe and the United Kingdom. This shift is thought to be due to the widespread use of griseofulvin, which is more effective against M. audounii than T. tonsurans; also, changes in immigration patterns and increases in international travel have likely spread T. tonsurans to new areas.[19] Another fungal species that has increased in prevalence is Trichophyton violaceum, especially in urban populations of the United Kingdom and Europe.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 1135. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "15. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. Archived from the original on 2023-07-02. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Rapini, Ronald P. (2021). "13. Fungal diseases". Practical Dermatopathology (Third ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-323-41788-4. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-06-16.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Tinea Capitis at eMedicine

- ↑ Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "15. Diseases of cutaneous appendages". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ↑ Degreef H. (2008). "Clinical forms of dermatophytosis (ringworm infection)". Mycopathologia. 166 (5–6): 257–65. doi:10.1007/s11046-008-9101-8. PMID 18478364.

- ↑ Ali S, Graham TA, Forgie SE (2007). "The assessment and management of tinea capitis in children". Pediatric Emergency Care. 23 (9): 662–65, quiz 666–8. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e31814efe06. PMID 17876261.

- ↑ Wigger-Alberti W, Elsner P (1997). "[Fluorescence with Wood's light. Current applications in dermatologic diagnosis, therapy follow-up and prevention]". Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift für Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete (in Deutsch). 48 (8): 523–7. doi:10.1007/s001050050622. PMID 9378631. Archived from the original on 2001-07-31. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ↑ Slowinska M, Rudnicka L, Schwartz RA, Kowalska-Oledzka E, Rakowska A, Sicinska J, Lukomska M, Olszewska M, Szymanska E (November 2008). "Comma hairs: a dermatoscopic marker for tinea capitis: a rapid diagnostic method". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 59 (5 Suppl): S77–9. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.009. PMID 19119131.

- ↑ Xu X, Elder DA, Elenitsa R, Johnson BL, Murphy GE (2008). Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7363-8.

- ↑ Richardson, p. 88.

- ↑ Gupta AK, Cooper EA (2008). "Update in antifungal therapy of dermatophytosis". Mycopathologia. 166 (5–6): 353–67. doi:10.1007/s11046-008-9109-0. PMID 18478357.

- ↑ Gupta AK, Summerbell RC (2000). "Tinea capitis". Medical Mycology. 38 (4): 255–87. doi:10.1080/714030949. PMID 10975696.

- ↑ Chen, Xiaomei; Jiang, Xia; Yang, Ming; González, Urbà; Lin, Xiufang; Hua, Xia; Xue, Siliang; Zhang, Min; Bennett, Cathy (2016-05-12). "Systemic antifungal therapy for tinea capitis in children". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (5): CD004685. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004685.pub3. ISSN 1465-1858. PMID 27169520. Archived from the original on 2021-01-18. Retrieved 2021-04-27.

- ↑ Blumer JL. (1999). "Pharmacologic basis for the treatment of tinea capitis". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 18 (2): 191–9. doi:10.1097/00006454-199902000-00027. PMID 10048701.

- ↑ Baertlein, Lisa (2007-09-28). "US FDA approves oral granules for scalp ringworm | Deals | Regulatory News | Reuters". Archived from the original on 2009-03-23. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

- ↑ Richardson, p. 83.

- ↑ Richardson, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Richardson, p. 84.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |