Sporotrichosis

| Sporotrichosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Rose thorn disease, rose gardener's disease,[1] rose handler's disease[2] | |

| |

| Sporotrichosis | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Firm painless nodules that later ulcerate.[3] |

| Causes | Sporothrix schenckii[1] |

| Diagnostic method | |

| Differential diagnosis | Leishmaniasis, nocardiosis, mycobacterium marinum,[3] cat-scratch disease, syphilis, leprosy, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis[1] |

| Treatment | Antifungals, surgery[1] |

| Medication | Itraconazole, posaconazole, amphotericin B[1] |

| Prognosis | Good with treatment, poor if widespread disease[1] |

Sporotrichosis, also known as rose handler's disease,[2] is a fungal infection that may be localised to skin, lungs, bone and joint, or be widespread.[2][4] It typically presents with firm painless large bumps in the skin that later ulcerate.[3] Following exposure to the fungus the disease typically progresses over a week to several months.[1] People with a weakened immune system may develop severe complications.[1]

The condition is caused by the fungus Sporothrix schenckii,[5] and others.[1] Because S. schenckii is naturally found in soil, hay, sphagnum moss, and plants, it usually affects farmers, gardeners, and agricultural workers.[6] It enters through small cuts in the skin to cause the infection.[1] In case of sporotrichosis affecting the lungs, the fungal spores enter by breathing in.[1] Sporotrichosis can also be acquired from handling cats with the disease; it is an occupational hazard for veterinarians.[1]

Treatment depends on the site and extent of infection.[1] Topical antifungals can be applied to skin lesions.[1] Deep infection in lungs may require surgery.[1] Medications used include Itraconazole, posaconazole and amphotericin B.[1] Most people recover with treatment.[1] The outcome is generally good unless there is a weak immune system or widespread disease.[1]

The causal fungus is found worldwide.[1] The species was named for Benjamin Schenck, a medical student who in 1896 was the first to isolate it from a human specimen.[7] It has been reported in cats,[1] mules, dogs, mice and rats.[3]

Signs and symptoms

- Cutaneous or skin sporotrichosis

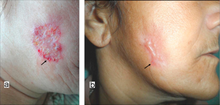

- This is the most common form of this disease. Symptoms of this form include nodular lesions or bumps in the skin, at the point of entry and also along lymph nodes and vessels. The lesion starts off small and painless, and ranges in color from pink to purple. Left untreated, the lesion becomes larger and look similar to a boil and more lesions will appear, until a chronic ulcer develops.

- Usually, cutaneous sporotrichosis lesions occur in the finger, hand, and arm.

- Pulmonary sporotrichosis

- This rare form of the disease occur when S. schenckii spores are inhaled. Symptoms of pulmonary sporotrichosis include productive coughing, nodules and cavitations of the lungs, fibrosis, and swollen hilar lymph nodes. Patients with this form of sporotrichosis are susceptible to developing tuberculosis and pneumonia

- Disseminated sporotrichosis

- When the infection spreads from the primary site to secondary sites in the body, the disease develops into a rare and critical form called disseminated sporotrichosis. The infection can spread to joints and bones (called osteoarticular sporotrichosis) as well as the central nervous system and the brain (called sporotrichosis meningitis).

- The symptoms of disseminated sporotrichosis include weight loss, anorexia, and appearance of bony lesions.

-

Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis

-

Lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis

-

Sporotrichosis by the fungus Sporothrix schenckii

Complications

Cutaneous lesions can become superinfected with bacteria, resulting in cellulitis.

Diagnosis

Sporotrichosis is a chronic disease with slow progression and often subtle symptoms. It is difficult to diagnose, as many other diseases share similar symptoms and therefore must be ruled out.

People with sporotrichosis will have antibody against the fungus S. schenckii, however, due to variability in sensitivity and specificity, it may not be a reliable diagnosis for this disease. The confirming diagnosis remains culturing the fungus from the skin, sputum, synovial fluid, and cerebrospinal fluid. Smears should be taken from the draining tracts and ulcers.

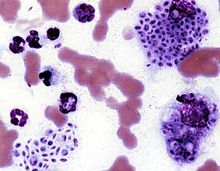

Cats with sporotrichosis are unique in that the exudate from their lesions may contain numerous organisms. This makes cytological evaluation of exudate a valuable diagnostic tool in this species. Exudate is pyogranulomatous and phagocytic cells may be packed with yeast forms. These are variable in size, but many are cigar-shaped.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes: leishmaniasis, nocardiosis, mycobacterium marinum,[3] cat-scratch disease, leprosy, syphilis, sarcoidosis and tuberculosis.[1]

Prevention

The majority of sporotrichosis cases occur when the fungus is introduced through a cut or puncture in the skin while handling vegetation containing the fungal spores. Prevention of this disease includes wearing long sleeves and gloves while working with soil, hay bales, rose bushes, pine seedlings, and sphagnum moss. Also, keeping cats indoors is a preventative measure.

Treatment

Treatment of sporotrichosis depends on the severity and location of the disease. The following are treatment options for this condition:[8]

- Oral potassium iodide

- Potassium iodide is an anti-fungal drug that is widely used as a treatment for cutaneous sporotrichosis. Despite its wide use, there is no high-quality evidence for or against this practice. Further studies are needed to assess the efficacy and safety of oral potassium iodide in the treatment of sporotrichosis.[9]

- Itraconazole (Sporanox) and fluconazole

- These are antifungal drugs. Itraconazole is currently the drug of choice and is significantly more effective than fluconazole. Fluconazole should be reserved for patients who cannot tolerate itraconazole.

- This antifungal medication is delivered intravenously. Many patients, however, cannot tolerate Amphotericin B due to its potential side effects of fever, nausea, and vomiting.

- Lipid formulations of amphotericin B are usually recommended instead of amphotericin B deoxycholate because of a better adverse-effect profile. Amphotericin B can be used for severe infection during pregnancy. For children with disseminated or severe disease, amphotericin B deoxycholate can be used initially, followed by itraconazole.[10]

- In case of sporotrichosis meningitis, the patient may be given a combination of Amphotericin B and 5-fluorocytosine/Flucytosine.

- 500mg and 1000mg daily dosages of terbinafine for twelve to 24 weeks has been used to treat cutaneous sporotrichosis.[11]

- Newer triazoles

- Several studies have shown that posaconazole has in vitro activity similar to that of amphotericin B and itraconazole; therefore, it shows promise as an alternative therapy. However, voriconazole susceptibility varies. Because the correlation between in vitro data and clinical response has not been demonstrated, there is insufficient evidence to recommend either posaconazole or voriconazole for treatment of sporotrichosis at this time.[10]

- In cases of bone infection and cavitary nodules in the lungs, surgery may be necessary.

- Heat creates higher tissue temperatures, which may inhibit fungus growth while the immune system counteracts the infection. The "pocket warmer" used for this purpose has the advantage of being able to maintain a constant temperature of 44 degrees-45 degrees C on the skin surface for several hours, while permitting unrestricted freedom of movement. The duration of treatment depends on the type of lesion, location, depth, and size. Generally, local application for 1-2 h per day, or in sleep time, for 5-6 weeks seems to be sufficient.[12]

Other animals

Sporotrichosis can be diagnosed in domestic and wild mammals. In veterinary medicine it is most frequently seen in cats and horses. Cats have a particularly severe form of cutaneous sporotrichosis and also can serve as a source of zoonotic infection to persons who handle them and are exposed to exudate from skin lesions.[13] It has been reported in mules, dogs, mice and rats.[3]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 Milner, Dan A.; Solomon, Isaac (2020). "Sporotrichosis". In Milner, Danny A. (ed.). Diagnostic Pathology: Infectious Diseases. Elsevier. pp. 316–319. ISBN 978-0-323-61138-1. Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Proia, Laurie (2020). "28. The dimorphic mycoses". In Spec, Andrej; Escota, Gerome V.; Chrisler, Courtney; Davies, Bethany (eds.). Comprehensive Review of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier. pp. 421–422. ISBN 978-0-323-56866-1. Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2021-07-12.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "13. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 314–315. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. Archived from the original on 2021-08-29. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ↑ Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "25. Mycoses and Algal infections". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 455. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-07-12.

- ↑ "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ↑ Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 654–6. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ↑ Barros MB, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach AO (October 2011). "Sporothrix schenckii and Sporotrichosis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 24 (4): 633–54. doi:10.1128/CMR.00007-11. PMC 3194828. PMID 21976602.

- ↑ Lortholary O, Denning DW, Dupont B (March 1999). "Endemic mycoses: a treatment update". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 43 (3): 321–31. doi:10.1093/jac/43.3.321. PMID 10223586.

- ↑ Xue S, Gu R, Wu T, Zhang M, Wang X (October 2009). "Oral potassium iodide for the treatment of sporotrichosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006136. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006136.pub2. PMC 7388325. PMID 19821356. Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Hogan BK, Hospenthal DR (March 2011). "Update on the therapy for sporotrichosis". Patient Care. 22: 49–52. Archived from the original on 2020-05-22. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- ↑ Chapman SW, Pappas P, Kauffmann C, Smith EB, Dietze R, Tiraboschi-Foss N, Restrepo A, Bustamante AB, Opper C, Emady-Azar S, Bakshi R (February 2004). "Comparative evaluation of the efficacy and safety of two doses of terbinafine (500 and 1000 mg day(-1)) in the treatment of cutaneous or lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis". Mycoses. 47 (1–2): 62–8. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0507.2003.00953.x. PMID 14998402.

- ↑ Takahashi S, Masahashi T, Maie O (October 1981). "[Local thermotherapy in sporotrichosis]". Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift für Dermatologie, Venerologie, und Verwandte Gebiete (in Deutsch). 32 (10): 525–8. PMID 7298332.

- ↑ "Sporotrichosis". The Merck Veterinary Manual. Archived from the original on 2019-06-17. Retrieved 2019-06-17.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |