Chromoblastomycosis

| Chromoblastomycosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Chromomycosis,[1] Cladosporiosis,[1] Fonseca's disease,[1] Pedroso's disease,[1] Phaeosporotrichosis,[1] or Verrucous dermatitis[1] | |

| |

| Chromoblastomycosis | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Symptoms | Skin lesions[2] |

| Complications | Squamous cell carcinoma[2] |

| Duration | Around 15 years from onset to diagnosis[2] |

| Causes | Entry of fungi through minor trauma,[2] |

| Frequency | 4M:F, 75% are farmers[2] |

Chromoblastomycosis is a long-term fungal infection of the skin and just under the skin, which following being injured, a small bump appears before forming a purplish roundish patch.[3][4] It tends to occur on the legs.[5] Gradually the nodules get bigger and the leg can swell.[2]

It can be caused by many different types of fungi which become implanted under the skin, often by thorns or splinters.[6]

Chromoblastomycosis spreads very slowly; it is rarely fatal and usually has a good prognosis, but it can be very difficult to cure. The several treatment options include medication and surgery.[7] Posaconazole at a dose of 800 mg divided throughout the day may be around 80% effective.[5] Depressed pale scarring is usually left behind.[5]

The infection occurs most commonly in rural areas of tropical and subtropical climates.[8]

Signs and symptoms

There is usually a history of injury.[9] A skin elevation appears gradually and becomes a purplish annular patch.[9] It usually stays local, rarely becoming systemic.[9]

Several complications may occur. Usually, the infection slowly spreads to the surrounding tissue while still remaining localized to the area around the original wound. However, sometimes the fungi may spread through the blood vessels or lymph vessels, producing metastatic lesions at distant sites. Another possibility is secondary infection with bacteria. This may lead to lymph stasis (obstruction of the lymph vessels) and elephantiasis. The nodules may become ulcerated, or multiple nodules may grow and coalesce, affecting a large area of a limb.[citation needed]

-

Chromoblastomycosis

-

Chromoblastomycosis

-

Chromoblastomycosis

-

Chromoblastomycosis

Cause

Chromoblastomycosis is believed to originate in minor trauma to the skin, usually from vegetative material such as thorns or splinters; this trauma implants fungi in the subcutaneous tissue. In many cases, the person will not notice or remember the initial trauma, as symptoms often do not appear for years. The fungi most commonly observed to cause chromoblastomycosis are:

- Fonsecaea pedrosoi[10][11]

- Cladophialophora bantiana causes both cutaneous chromoblastomycosis and systemic phaeohyphomycosis

- Phialophora verrucosa[12]

- Cladophialophora carrionii

- Fonsecaea compacta[13]

Mechanism

Over months to years, an erythematous papule appears at the site of inoculation. Although the mycosis slowly spreads, it usually remains localized to the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Hematogenous and/or lymphatic spread may occur. Multiple nodules may appear on the same limb, sometimes coalescing into a large plaque. Secondary bacterial infection may occur, sometimes inducing lymphatic obstruction. The central portion of the lesion may heal, producing a scar, or it may ulcerate.[citation needed]

-

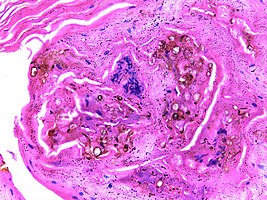

Micrograph of chromoblastomycosis showing sclerotic bodies

-

A 34-year-old man with a 12-year history of chromoblastomycosis and electron micrograph of his skin showing Fonsecaea pedrosoi spores.

Diagnosis

The most informative test is to scrape the lesion and add potassium hydroxide (KOH), then examine under a microscope. (KOH scrapings are commonly used to examine fungal infections.) The pathognomonic finding is observing medlar bodies (also called muriform bodies or sclerotic cells). Scrapings from the lesion can also be cultured to identify the organism involved. Blood tests and imaging studies are not commonly used.

On histology, chromoblastomycosis manifests as pigmented yeasts resembling "copper pennies".[9]

Special stains, such as periodic acid schiff and Gömöri methenamine silver, can be used to demonstrate the fungal organisms if needed.[citation needed]

Prevention

No preventive measure is known aside from avoiding the traumatic inoculation of fungi. At least one study found a correlation between walking barefoot in endemic areas and occurrence of chromoblastomycosis on the foot.[citation needed]

Treatment

Chromoblastomycosis is very difficult to cure. The primary treatments of choice are:[citation needed]

- Itraconazole, an antifungal azole, is given orally, with or without flucytosine.

- Alternatively, cryosurgery with liquid nitrogen has also been shown to be effective.

Other treatment options are the antifungal drug terbinafine,[14] another antifungal azole posaconazole, and heat therapy.

Antibiotics may be used to treat bacterial superinfections.[citation needed]

Amphotericin B has also been used.[15]

Prognosis

The prognosis for chromoblastomycosis is very good for small lesions. Severe cases are difficult to cure, although the prognosis is still quite good. The primary complications are ulceration, lymphedema, and secondary bacterial infection. A few cases of malignant transformation to squamous cell carcinoma have been reported. Chromoblastomycosis is very rarely fatal.[citation needed]

Epidemiology

Chromoblastomycosis occurs around the world, but is most common in rural areas between approximately 30°N and 30°S latitude. Madagascar and Japan have the highest incidence. Over two-thirds of patients are male, and usually between the ages of 30 and 50. A correlation with HLA-A29 suggests genetic factors may play a role, as well.[citation needed]

Society and culture

Chromoblastomycosis is considered a neglected tropical disease, affects mainly people living in poverty, and causes considerable morbidity, stigma and discrimination.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2019). "13. Diseases resulting from fungi and yeasts". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 316–317. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. Archived from the original on 2023-01-12. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ↑ Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "25. Mycoses and Algal infections". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 453. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ↑ "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Archived from the original on 1 August 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Morris-Jones, Rachael (2019). "18. Tropical dermatology". In Morris-Jones, Rachael (ed.). ABC of Dermatology (7th ed.). Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-119-48899-6. Archived from the original on 2023-06-30. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ↑ "Chromoblastomycosis | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-03-18. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ "Chromoblastomycosis | DermNet New Zealand". www.dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Santos, Daniel Wagner C. L.; de Azevedo, Conceição de Maria Pedrozo E. Silva; Vicente, Vania Aparecida; Queiroz-Telles, Flávio; Rodrigues, Anderson Messias; de Hoog, G. Sybren; Denning, David W.; Colombo, Arnaldo Lopes (August 2021). "The global burden of chromoblastomycosis". PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 15 (8): e0009611. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0009611. ISSN 1935-2735. PMID 34383752. Archived from the original on 2021-08-22. Retrieved 2021-08-22.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Johnstone, Ronald B. (2017). "25. Mycoses and Algal infections". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 453. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0. Archived from the original on 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2021-05-27.

- ↑ Bonifaz A, Carrasco-Gerard E, Saúl A (2001). "Chromoblastomycosis: clinical and mycologic experience of 51 cases". Mycoses. 44 (1–2): 1–7. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0507.2001.00613.x. PMID 11398635.

- ↑ de Andrade TS, Cury AE, de Castro LG, Hirata MH, Hirata RD (March 2007). "Rapid identification of Fonsecaea by duplex polymerase chain reaction in isolates from patients with chromoblastomycosis". Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 57 (3): 267–72. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.08.024. PMID 17338941.

- ↑ Park SG, Oh SH, Suh SB, Lee KH, Chung KY (March 2005). "A case of chromoblastomycosis with an unusual clinical manifestation caused by Phialophora verrucosa on an unexposed area: treatment with a combination of amphotericin B and 5-flucytosine". Br. J. Dermatol. 152 (3): 560–4. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06424.x. PMID 15787829. S2CID 41788722.

- ↑ Attapattu MC (1997). "Chromoblastomycosis--a clinical and mycological study of 71 cases from Sri Lanka". Mycopathologia. 137 (3): 145–51. doi:10.1023/A:1006819530825. PMID 9368408. S2CID 26091759.

- ↑ Bonifaz A, Saúl A, Paredes-Solis V, Araiza J, Fierro-Arias L (February 2005). "Treatment of chromoblastomycosis with terbinafine: experience with four cases". J Dermatolog Treat. 16 (1): 47–51. doi:10.1080/09546630410024538. PMID 15897168. S2CID 45956388. Archived from the original on 2021-07-18. Retrieved 2019-09-12.

- ↑ Paniz-Mondolfi AE, Colella MT, Negrín DC (March 2008). "Extensive chromoblastomycosis caused by Fonsecaea pedrosoi successfully treated with a combination of amphotericin B and itraconazole". Med. Mycol. 46 (2): 179–84. doi:10.1080/13693780701721856. PMID 18324498.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from July 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Pages with broken file links

- Articles with unsourced statements from May 2021

- Mycosis-related cutaneous conditions

- Neglected tropical diseases

- Tropical diseases