Moderna COVID-19 vaccine

Vials of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine | |

| Vaccine description | |

|---|---|

| Target disease | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Type | mRNA |

| Names | |

| Pronunciation | /məˈdɜːrnə/ mə-DUR-nə[1] |

| Trade names | Spikevax[2] |

| Other names | mRNA-1273, CX-024414, COVID-19 mRNA vaccine Moderna, TAK-919, COVID-19 vaccine moderna intramuscular injection[3] |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | COVID-19 vaccine[2] |

| Main uses | Prevent COVID-19[4] |

| Side effects | Pain at the injection site, tiredness, fever, swollen lymph nodes, headache, muscle pains[2] |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | Intramuscular |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a621002 |

| Legal | |

| License data | |

| Legal status |

|

Moderna COVID‑19 vaccine, known by the generic name elasomeran and brand name Spikevax, is a COVID-19 vaccine.[2][26] It is used in people over the age of eleven or seventeen, depending on the jurisdiction, to provide protection against COVID-19.[4][2][27] It was initially found to be 94% effective.[27] It is given as two or three 0.5 mL doses by injection into a muscle at least 28 days apart.[4]

Most side effects are mild to moderate and resolve within a few days.[2] These may include pain at the injection site, tiredness, fever, swollen lymph nodes, headache, and muscle pains.[2] Rare side effects may include anaphylaxis, facial palsy, pericarditis, and myocarditis.[2] There is no evidence of harm with use in pregnancy.[5] It is an mRNA vaccine, composed of nucleoside-modified mRNA (modRNA) encoding the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, which is encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles.[28]

The vaccine received emergency use authorization (EUA) in the United States in December 2020 and was approved for medical use in Europe in January of 2021.[4][2] It is authorized for use at some level in at least 86 countries as of 2022.[29][30] In 2020 it was being sold to governments at about 35 USD per dose.[31] It was developed by American company Moderna, the United States National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA).[32] It was the first COVID-19 vaccine to be studied in humans.[33]

Medical uses

The Moderna COVID‑19 vaccine is used to provide protection against infection by the SARS-CoV-2 virus in order to prevent COVID‑19.[22][2]

The vaccine is given by intramuscular injection into the deltoid muscle on the shoulder.[24] The initial course consists of two doses.[24] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends an interval of 28 days between doses.[34] Data show that first dose efficacy persists for up to ten weeks.[34] Therefore, to avoid deaths where supplies are limited, the WHO recommends delaying the second dose by up to 12 weeks to achieve high coverage of the first dose in high-priority groups.[34]

There is no evidence that a third booster dose is needed to prevent severe disease in healthy adults.[35][36][34] A third dose can be added after 28 days for immunocompromised people in some countries.[37][38] On 20 October 2021, the FDA approved a single booster dose consisting of half of the primary dose given six months after the initial course for people aged 65 and older and for people at high risk of severe COVID-19 or with frequent exposure to SARS-CoV-2.[39]

Effectiveness

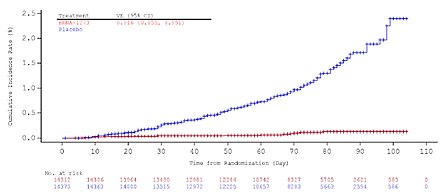

Evidence of vaccine efficacy starts about two weeks after the first dose.[40] High efficacy is achieved with full immunization, two weeks after the second dose, and was evaluated at 94.1%: at the end of the vaccine study that led to emergency authorization in the US, there were eleven cases of COVID‑19 in the vaccine group (out of 15,181 people) versus 185 cases in the placebo group (15,170 people).[40] Moreover, there were zero cases of severe COVID‑19 in the vaccine group, versus eleven in the placebo group.[41] This efficacy has been described as "astonishing"[42] and "borderline historic"[43] for a respiratory virus vaccine, and it is similar to the efficacy of the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine.[44][45]

Efficacy estimates were similar across age groups, sexes, racial and ethnic groups, and participants with medical comorbidities associated with high risk of severe COVID‑19.[46] Only individuals aged 18 or older were studied. Studies are underway to gauge efficacy and safety in children aged 0–11 (KidCOVE) and 12–17 (TeenCOVE).[47]

A further study conducted by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) between December 2020, and March 2021, on nearly 4 thousand health care personnel, first responders, and other essential and frontline workers concluded that under real-world conditions, mRNA vaccine effectiveness of full immunization (14 days or more after second dose) was 90% against SARS-CoV-2 infections, regardless of symptoms, and vaccine effectiveness of partial immunization (14 days or more after first dose but before second dose) was 80%.[48]

The duration of protection provided by the vaccine is unknown as of April 2021[update],[28][49] and a two-year followup study is underway to determine the duration.[43]

Preliminary results from a Phase III trial indicate that vaccine efficacy is durable, remaining at 93% six months after the second dose.[50]

The high efficacy of the vaccine already after the first dose[51](i.e. with suboptimal antibody titers), the observation that its immunogenicity even at quarter or half of the standard dose is substantial[52] and the observed dose-side effect relationship[52][51] has led to personalized vaccination concepts: epidemic modelling using Moderna vaccine characteristics predicts[53][54] that in a setting of limited vaccine availability,[55] when a wave of virus Variants of Concern hits a country, the societal benefit of vaccination may be enhanced and accelerated by a personalized dosing strategy, adapted to the state of the pandemic, country demographics, age of the recipients, availability of vaccines, and individual risk for severe disease. Using standard dosing in the elderly will reduce severe disease and deaths as shown in the pivotal study,[28] reduced dosing (thus multiplying the number of early recipients) in the healthy young that drive the pandemic spread through frequent social contacts may stop the pandemic earlier while still eliciting a sufficient immune response,[52][56][57][58] and giving an additional booster dose to the immunosuppressed[59] may optimize vaccine efficacy in this subpopulation known for weak immune response to vaccination.

A vaccine is generally considered effective if the estimate is ≥50% with a >30% lower limit of the 95% confidence interval.[60] Effectiveness is generally expected to slowly decrease over time.[61]

On 27 August, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a study reporting that the effectiveness against infection decreased from 91% (81–96%) to 66% (26–84%) when the Delta variant became predominant in the US, which may be due to unmeasured and residual confounding related to a decline in vaccine effectiveness over time.[62]

| Doses | Severity of illness | Delta[lower-alpha 1] | Alpha[lower-alpha 2] | Gamma[lower-alpha 2] | Beta[lower-alpha 2] | Others circulating previously[lower-alpha 2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Asymptomatic | 62% (−10 to 87%) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Symptomatic | 83% (65–91%) | 61% (56–66%) | 43% (22–59%) | 61% (53–67%) | ||

| Hospitalization | 87% (−1 to 98%) | 59% (39–73%) | 56% (−9 to 82%) | 76% (46–90%) | ||

| 2 | Asymptomatic | 54% (33–68%) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Symptomatic | 74% (66–80%) | 90% (85–94%) | 88% (61–96%) | 93% (87–96%) | ||

| Hospitalization | 96% (72–100%) | 94% (59–99%) | 100%[lower-alpha 3] | 90% (80–100%) | ||

Pregnancy

Limited data are available on the safety of the Moderna COVID‑19 vaccine for people who are pregnant.[65] The initial study excluded pregnant women or discontinued them from vaccination upon a positive pregnancy test.[40] Studies in animals found no safety concerns and clinical trials are underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of COVID‑19 vaccines in pregnant people.[65] Real-world observations through the CDC v-safe tracking program have not uncovered unusual numbers of adverse events or outcomes of interest.[66] Based on the results of a preliminary study, the US CDC recommends that pregnant people get vaccinated with the COVID‑19 vaccine.[67][68]

Side effects

The World Health Organization (WHO) stated that "the safety data supported a favorable safety profile" and that the vaccine's side effect profile "did not suggest any specific safety concerns".[40] The most common events were pain at the injection site, fatigue, headache, myalgia (muscle pain), and arthralgia (joint pain).[40]

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported anaphylaxis (a severe allergic reaction) in 2.5 cases per million doses and has recommended a 15-minute observation period after injection.[70] Delayed skin reactions at injection sites resulting in rash-like redness have also been observed in rare cases but are not considered serious or contraindications to subsequent vaccination.[71] The rate for local redness is about 10.8%, in 1.9% of cases this may extend to a size of 100 mm or greater.[72]

In June 2021, the US CDC confirmed that myocarditis or pericarditis occurs in about 13 of every million young people, mostly male and over the age of 16, who received the Moderna or the Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine. Most affected individuals recover quickly with adequate treatment and rest.[73]

In October 2021, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and Denmark paused the use of the Moderna vaccine in young people, offering or recommending the similar Pfizer–BioNTech vaccine instead. This policy was a precautionary measure following the release of an unpublished study reporting an increased incidence of treatable mild myocarditis and pericarditis occurring more frequently in young men after the second dose of mRNA vaccines, with a higher incidence with Moderna. Health regulators in the US, EU and WHO said the vaccine's benefits still outweighed the risks,[74][75][76] and the WHO considered the overall risk to be small.[77] On 10 November, Germany's vaccine advisory recommended the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine instead of the Moderna vaccine for people under 30 years of age and pregnant women.[78]

Pharmacology

Moderna's technology uses a nucleoside-modified messenger RNA (modRNA) compound codenamed mRNA-1273. Once the compound is inside a human cell, the mRNA links up with the cell's endoplasmic reticulum. The mRNA-1273 is encoded to trigger the cell into making a specific protein using the cell's normal manufacturing process. The vaccine encodes a version of the spike protein with a modification called 2P, in which the protein includes two stabilizing mutations in which the original amino acids are replaced with prolines, developed by researchers at the University of Texas at Austin and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases' Vaccine Research Center.[79][80][81][82][unreliable medical source?] Once the protein is expelled from the cell, it is eventually detected by the immune system, which begins generating efficacious antibodies. The mRNA-1273 drug delivery system uses a PEGylated lipid nanoparticle drug delivery (LNP) system.[83]

Chemistry

The vaccine contains the following ingredients:[22][72]

The active ingredient is an mRNA sequence containing a total of 4101 nucleotides that encodes the full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein,[84] with two mutations (K986P and V987P) designed to stabilize the pre-fusion conformation. The sequence is further optimized by:[85][86]

- all uridines (U) substituted with N1-methylpseudouridine (U → m1Ψ),

- flanked by an artificial 5' untranslated region (UTR) and a 3' UTR derived from the human alpha globin gene (HBA1),

- introduction of two additional stop codons,

- terminated by a 3' poly(A) tail.

A putative sequence of the vaccine has been published on a forum for professional virologists, obtained by direct sequencing of residual vaccine material in used vials.[87]

The vaccine mRNA is dissolved in an aqueous buffer containing tromethamine, tromethamine hydrochloride, sodium acetate, and sucrose.[24] The mRNA is encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles that stabilize the mRNA and facilitate its entry into cells.[28] The nanoparticles are manufactured from the following lipids:

- 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC),[24]

- cholesterol,[24]

- PEG2000-DMG (polyethylene glycol (PEG) 2000-dimyristoyl glycerol (DMG)),[24] and

- SM-102[24]

History

In January 2020, Moderna announced development of an RNA vaccine, codenamed mRNA-1273, to induce immunity to SARS-CoV-2.[88][89][90] It entered phase I trial on 16 March, 63 days after sequence selection, and was the first COVID-19 vaccine to be given to humans.[33]

Moderna received US$955 million from BARDA, an office of the US Department of Health and Human Services. BARDA funded 100% of the cost of bringing the vaccine to FDA licensure.[91][32]

The United States government provided US$2.5 billion in total funding for the Moderna COVID‑19 vaccine (mRNA-1273).[92] Private donors also made contributions to the vaccine's development. The Dolly Parton COVID-19 Research Fund contributed with US$1 million.[93]

Authorizations

Expedited

As of December 2020, mRNA-1273 was under evaluation for emergency use authorization (EUA) by multiple countries which would enable rapid rollout of the vaccine in the United Kingdom, the European Union, Canada, and the United States.[94][95][96][97]

On 18 December 2020, mRNA-1273 was authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under an EUA.[21][23][98] This is the first product from Moderna that has been authorized by the FDA.[99][100]

On 23 December 2020, mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 was authorized by Health Canada.[101][13][11]

On 5 January 2021, mRNA-1273 was authorized for use in Israel by its Ministry of Health.[102]

On 3 February 2021, mRNA-1273 was authorized for use in Singapore by its Health Sciences Authority.[103]

On 30 April 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) granted emergency use listing.[104][105]

On 5 May 2021, mRNA-1273 was authorized for emergency use in the Philippines by the Philippines Food and Drug Administration.[106]

On 21 May 2021, COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna Intramuscular Injection (formerly TAK-919) was authorized for emergency use in Japan.[3]

On 29 June 2021, mRNA-1273 was authorized for use in India by the Drugs Controller General of India.[107] The same day, the vaccine was also approved by the Ministry of Health of Vietnam for emergency use in the country.[108]

On 5 August 2021, Malaysia's National Pharmaceutical Regulatory Agency (NPRA) has given conditional registration for emergency use of the vaccine in the country.[109]

Standard

On 6 January 2021, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommended granting conditional marketing authorization[2][110] and the recommendation was accepted by the European Commission the same day.[25][111] On 23 July 2021, the EMA extended the use of the COVID‑19 Vaccine Moderna to include people aged 12 to 17.[112]

On 12 January 2021, Swissmedic granted temporary authorization for the Moderna COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine in Switzerland.[113][114]

On 31 March 2021, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) granted conditional marketing authorization in the United Kingdom.[17][19][20]

On 9 August 2021, Spikevax was granted provisional approval in Australia.[8] The approval was updated on 4 September 2021, to include people aged twelve and older.[9]

The Moderna Spikevax COVID-19 vaccine was authorized in Canada on 16 September 2021, for people aged 12 and older.[12][11][115]

Further development

It remains unknown whether the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine provides life-long immunity or if periodic booster shots are required.[116] Pregnant and breastfeeding women were also excluded from the initial trials used to obtain Emergency Use Authorization,[117] though trials in those populations are expected to be performed in 2021.[118]

In January 2021, Moderna announced that it would offer a third dose of its vaccine to people who were vaccinated twice in its Phase I trial. The booster would be made available to participants six to twelve months after they got their second dose. The company said it may also study a third shot in participants from its Phase III trial, if antibody persistence data warranted it.[119][120][121]

In 2020, Moderna partnered with Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, and the Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW).[122][123] The vaccine is known as "COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna Intramuscular Injection".[124][3]

On 25 January 2021, Moderna started development of a new form of its vaccine, called mRNA-1273.351, that could be used as a booster shot against the Beta variant (lineage B.1.351).[125][126] It also started testing to see if a third shot of the existing vaccine could be used to fend off the virus variants.[126] On 24 February, Moderna announced that it had manufactured and shipped sufficient amounts of mRNA-1273.351 to the National Institutes of Health to run Phase I clinical trials.[127] On 16 March 2021, in order to increase the span of vaccination beyond adults, Moderna started the clinical trials of vaccines on children age 6-months to 11-years-old in the US and in Canada (KidCove),[128] in addition to the existing and fully-enrolled study on 12-17 year-olds (TeenCOVE).[129][130]

Moderna is also investigating a multivalent booster, mRNA-1273.211, which combines a 50-50 mix of mRNA-1273 and mRNA-1273.351.[131][132]

Homologous prime-boost

In August 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) authorized the use of an additional mRNA vaccine dose for immunocompromised individuals.[37][38]

In September 2021, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) started evaluating the use of a booster dose of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine to be given at least six months after the second dose in people aged twelve years and older.[133][134]

On 4 October 2021, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) stated that people with "severely weakened" immune systems can receive an extra dose of either the Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine or the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine starting at least 28 days after their second dose.[135]

In October 2021, the FDA and the CDC authorized the use of either homologous or heterologous vaccine booster doses.[39][136][137]

Heterologous prime-boost

In October 2021, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) authorized the use of either homologous or heterologous vaccine booster doses.[39][136] The authorization was expanded to include all adults in November 2021.[137]

Society and culture

Names

mRNA-1273 was the code name during development and testing,[28][100] elasomeran is the proposed international nonproprietary name (pINN),[26][85] and Spikevax is the brand name.[2]

Economics

In June 2020, Singapore signed a pre-purchase agreement for Moderna, reportedly paying a price premium in order to secure early stock of vaccines, although the government declined to provide the actual price and quantity, citing commercial sensitivities and confidentiality clauses.[138][139]

On 11 August 2020, the US government signed an agreement to buy 100 million doses of Moderna's anticipated vaccine,[140] which the Financial Times said Moderna planned to price at US$50–60 per course.[141] In November 2020, Moderna said it will charge governments who purchase its vaccine between US$25 and US$37 per dose while the EU is seeking a price of under US$25 per dose for the 160 million doses it plans to purchase from Moderna.[142][143]

In 2020, Moderna obtained purchase agreements for mRNA-1273 with the European Union for 160 million doses and with Canada for up to 56 million doses.[144][145] On 17 December, a tweet by the Belgium Budget State Secretary revealed the E.U. would pay US$18 per dose, while The New York Times reported that the US would pay US$15 per dose.[146]

In February 2021, Moderna said it was expecting US$18.4 billion in sales of its COVID-19 vaccine.[147]

Manufacture

Moderna is relying extensively on contract manufacturing organizations to scale up its vaccine manufacturing process. The first step of the process—synthesis of DNA plasmids (to be used as a template for synthesis of mRNA)—has been handled by a contractor called Aldevron based in Fargo, North Dakota.[148] For the remainder of the process, Moderna contracted with Lonza Group to manufacture the vaccine at facilities in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in the United States, and in Visp in Switzerland, and purchased the necessary lipid excipients from CordenPharma.[149] Besides CMOs, Moderna also manufactures the vaccine at its own production facility in Norwood, Massachusetts.[150]

For the tasks of filling and packaging vials (fill and finish), Moderna entered into contracts with Catalent in the United States and Laboratorios Farmacéuticos Rovi in Spain.[149] In April 2021, Moderna expanded its agreement with Catalent to increase manufacturing output at the latter's plant in Bloomington, Indiana. The expansion will allow Catalent to manufacture up to 400 vials per minute and fill an additional 80 million vials per year.[151] Later that month, Moderna announced its plans to spend billions of dollars to boost production of its vaccines, potentially tripling the output in 2022, claiming as well that it would make no less than 800 million doses in 2021. The increase in production is in part attributed to improvements made by the company in manufacturing methods.[152][153][154]

The Moderna news followed preliminary results from the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine candidate, BNT162b2, with Moderna demonstrating similar efficacy, but requiring storage at the temperature of a standard medical refrigerator of 2–8 °C (36–46 °F) for up to thirty days or −20 °C (−4 °F) for up to four months, whereas the Pfizer-BioNTech candidate requires ultracold freezer storage between −80 and −60 °C (−112 and −76 °F).[155][116] Low-income countries usually have cold chain capacity for only standard refrigerator storage, not ultracold freezer storage.[156][157] In February 2021, the restrictions on the Pfizer vaccine were relaxed when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) updated the emergency use authorization (EUA) to permit undiluted frozen vials of the vaccine to be transported and stored at between −25 and −15 °C (−13 and 5 °F) for up to two weeks before use.[72][158][159] The Moderna vaccine should not be stored at a temperature below −50 °C (−58 °F).[160]

In November 2020, Nature reported that "While it's possible that differences in LNP formulations or mRNA secondary structures could account for the thermostability differences [between Moderna and BioNtech], many experts suspect both vaccine products will ultimately prove to have similar storage requirements and shelf lives under various temperature conditions."[161]

Patent litigation

The PEGylated lipid nanoparticle (LNP) drug delivery system of mRNA-1273 has been the subject of ongoing patent litigation with Arbutus Biopharma, from whom Moderna had previously licensed LNP technology.[83][162] On 4 September 2020, Nature Biotechnology reported that Moderna had lost a key challenge in the ongoing case.[163]

Controversies

In May 2020, after releasing partial and non-peer reviewed results for only eight of 45 candidates in a preliminary pre-Phase I stage human trial directly to financial markets, the CEO announced on CNBC an immediate $1.25 billion rights issue to raise funds for the company, at a $30 billion valuation,[164] while Stat said, "Vaccine experts say Moderna didn't produce data critical to assessing COVID-19 vaccine."[165]

On 7 July 2020, disputes between Moderna and government scientists over the company's unwillingness to share data from the clinical trials were revealed.[166]

Moderna also faced criticism for failing to recruit people of color in clinical trials.[167]

On 18 August 2021, the US Department of Health and Human Services announced a plan to offer a booster dose eight months after the second dose, citing evidence of reduced protection against mild and moderate disease and the possibility of reduced protection against severe disease, hospitalization, and death.[168] Scientists and the WHO reaffirmed the lack of evidence on the need for a booster dose for healthy people and that the vaccine remains effective against severe disease months after administration.[35] In a statement, the WHO and SAGE said that, while protection against infection may be diminished, protection against severe disease will likely be retained due to cell-mediated immunity.[36] Research into optimal timing for boosters is still ongoing, and a booster too early may lead to less robust protection.[169]

On 26 August 2021, Japan suspended the use of more than 1.6 million doses of the Moderna vaccine after reports of contaminated vials.[170]

Misinformation

Videos on video-sharing platforms circulated around May 2021 showing people having magnets stick to their arms after receiving the vaccine, purportedly demonstrating the conspiracy theory that vaccines contain microchips, but these videos have been debunked.[171][172][173][174]

In November 2021, a White House correspondent for the conservative outlet Newsmax falsely tweeted that the Moderna vaccine contained luciferase "so that you can be tracked."[175][176]

Research

On 15 March 2021, Moderna's second COVID‑19 vaccine (mRNA-1283) started phase I clinical trials. This vaccine candidate can potentially be kept in refrigerators instead of freezers, making distributions easier especially in developing countries.[177][178]

Phase I–II

In March 2020, the Phase I human trial of mRNA-1273 began in partnership with the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.[179] In April, the US Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) allocated up to $483 million for Moderna's vaccine development.[180] Plans for a Phase II dosing and efficacy trial to begin in May were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[181] Moderna signed a partnership with Swiss vaccine manufacturer Lonza Group,[182] to supply 300 million doses per annum.[183]

On 25 May 2020, Moderna began a Phase IIa clinical trial recruiting six hundred adult participants to assess safety and differences in antibody response to two doses of its candidate vaccine, mRNA-1273, a study expected to complete in 2021.[184]

On 14 July 2020, Moderna scientists published preliminary results of the Phase I dose escalation clinical trial of mRNA-1273, showing dose-dependent induction of neutralizing antibodies against S1/S2 as early as 15 days post-injection. Mild to moderate adverse reactions, such as fever, fatigue, headache, muscle ache, and pain at the injection site were observed in all dose groups, but were common with increased dosage.[86] The vaccine in low doses was deemed safe and effective in order to advance a Phase III clinical trial using two 100-μg doses administered 29 days apart.[86]

In July 2020, Moderna announced in a preliminary report that its Operation Warp Speed candidate had led to production of neutralizing antibodies in healthy adults in Phase I clinical testing.[86][185] "At the 100-microgram dose, the one Moderna is advancing into larger trials, all 15 patients experienced side effects, including fatigue, chills, headache, muscle pain, and pain at the site of injection."[186] The troublesome higher doses were discarded in July from future studies.[186]

On 14 September 2021, a study funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases reported a strong immune response after six months, even at low doses, suggesting that more doses could be deployed from a limited vaccine supply. Six months after low-dose vaccination, 67% of participants still had memory cytotoxic T cells, suggesting that immune memory is stable. The study also found that cross-reactive T cells acquired during infection with other coronaviruses that cause the common cold increased the response to the vaccine.[187][188]

Phase III

Moderna and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases began a Phase III trial in the US on 27 July, with a plan to enroll and assign thirty-thousand volunteers to two groups – one group receiving two 100-μg doses of mRNA-1273 vaccine and the other receiving a placebo of 0.9% sodium chloride.[189] As of 7 August, more than 4,500 volunteers had enrolled.[citation needed]

In September 2020, Moderna published the detailed study plan for the clinical trial.[190] On 30 September, CEO Stéphane Bancel said that, if the trial is successful, the vaccine might be available to the public as early as late March or early April 2021.[191] As of October 2020, Moderna had completed the enrollment of 30,000 participants needed for its Phase III trial.[192] The US National Institutes of Health announced on 15 November 2020, that overall trial results were positive.[193]

Since September 2020, Moderna has used Roche Diagnostics' Elecsys Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S test, authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) under an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) on 25 November 2020. According to an independent supplier of clinical assays in microbiology, "this will facilitate the quantitative measurement of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and help to establish a correlation between vaccine-induced protection and levels of anti-receptor binding domain (RBD) antibodies." The partnership was announced by Roche on 9 December 2020.[194]

A review by the FDA in December 2020, of interim results of the Phase III clinical trial on mRNA-1273 showed it to be safe and effective against COVID‑19 infection resulting in the issuance of an EUA by the FDA.[98]

In February 2021, results from Phase III clinical trial were published in the New England Journal of Medicine, indicating 94% efficacy in preventing COVID‑19 infection.[28][116][195] Side effects included flu-like symptoms, such as pain at the injection site, fatigue, muscle pain, and headache.[116] The clinical trial is ongoing and is set to conclude in late 2022.[196]

Notes

References

- ↑ Moderna (23 October 2019). mRNA-3704 and Methylmalonic Acidemia (Video). YouTube. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 "Spikevax (previously COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna) EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 4 January 2021. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Takeda Announces Approval of Moderna's COVID-19 Vaccine in Japan" (Press release). Takeda. 21 May 2021. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "COVID-19 Vaccine (Moderna) Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Spikevax". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 9 August 2021. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Spikevax (elasomeran) Covid-19 Vaccine Product Information Licence" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 18 August 2021. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ↑ "Summary For Artg Entry: 370599 Spikevax (elasomeran) Covid-19 Vaccine 0.2 Mg/Ml Suspension For Injection Vial" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Retrieved 28 August 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ 8.0 8.1 "COVID-19 vaccine: Spikevax (elasomeran)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 9 August 2021. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "TGA Provisional Approval of Moderna COVID-19 vaccine to include 12-17 years age group". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 4 September 2021. Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- ↑ "Covax Facility" (in Portuguese). Federal government of Brazil. Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency. 25 June 2021. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Moderna Spikevax COVID-19 vaccine". Health Canada. 23 December 2020. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine (mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2)". COVID-19 vaccines and treatments portal. 23 December 2020. Archived from the original on 23 December 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ↑ "Regulatory Decision Summary - COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna". Health Canada. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ↑ "Archive copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-03. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Regulatory Decision Summary - Spikevax". Health Canada. 13 November 2020. Archived from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Summary of Product Characteristics for Spikevax". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 20 August 2021. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ↑ "Regulatory approval of Spikevax (formerly COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna)". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 8 January 2021. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Regulatory approval of Spikevax (formerly COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna)". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 8 January 2021. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Summary of the Public Assessment Report for Spikevax". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). 19 February 2021. Archived from the original on 22 April 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "FDA Takes Additional Action in Fight Against COVID-19 By Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for Second COVID-19 Vaccine". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine – cx-024414 injection, suspension". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine Emergency Use Authorization (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Report). 12 August 2021. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 "Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine Standing Orders for Administering Vaccine to Persons 18 Years of Age and Older" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 16 July 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2021.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "European Commission authorises second safe and effective vaccine against COVID-19". European Commission (Press release). Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "TGA grants provisional determination for the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, Elasomeran". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) (Press release). 24 June 2021. Archived from the original on 27 June 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Moderna COVID-19 vaccine". Health Canada. 23 December 2020. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. (February 2021). "Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (5): 403–416. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. PMC 7787219. PMID 33378609.

- ↑ "Moderna COVID-19 vaccine - WikiProjectMed". mdwiki.org. The New York Times. Januarary 28 2022. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ↑ "COVID-19 Vaccine Tracker: Moderna: mRNA-1273". McGill University. Archived from the original on 2021-12-13. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ↑ Jr, Berkeley Lovelace (5 August 2020). "Moderna is pricing coronavirus vaccine at $32 to $37 per dose for some customers". CNBC. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Clouse A (24 November 2020). "Fact check: Moderna vaccine funded by government spending, with notable private donation". USA Today. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Whittacker, Elizabeth; Heath, Paul T. (2021). "27. COVID-19 in children and COVID-19 vaccines". In Vesikari, Timo; Damme, Pierre Van (eds.). Pediatric Vaccines and Vaccinations: A European Textbook (Second ed.). Switzerland: Springer. p. 299. ISBN 978-3-030-77172-0. Archived from the original on 2022-01-29. Retrieved 2022-01-29.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Interim recommendations for use of the Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccine against COVID-19 (Guidance). World Health Organization (WHO). June 2021. hdl:10665/341785. WHO/2019-nCoV/vaccines/SAGE_recommendation/mRNA-1273/2021.2.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "The WHO is right to call a temporary halt to COVID vaccine boosters". Nature (Editorial). 596 (7872): 317. 17 August 2021. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..317.. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02219-w. PMID 34404945. S2CID 237199262. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "Interim statement on COVID-19 vaccine booster doses" (Press release). World Health Organization. 10 August 2021. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Additional Vaccine Dose for Certain Immunocompromised Individuals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 12 August 2021. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "COVID-19 Vaccines for Moderately to Severely Immunocompromised People". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 13 August 2021. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Takes Additional Actions on the Use of a Booster Dose for COVID-19 Vaccines". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 21 October 2021. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 Background document on the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna) against COVID-19 (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). February 2021. hdl:10665/339218. WHO/2019-nCoV/vaccines/SAGE_recommendation/mRNA-1273/background/2021.1. Archived from the original on 2021-06-13. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- Lay summary in: Background document on the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna) against COVID-19 (Report).

- ↑ Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting (PDF) (Report). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Branswell H (2 February 2021). "Comparing the Covid-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson". Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Moderna Vaccine Shows Significant COVID-19 Prevention Efficacy in Phase 3 Data". Archived from the original on 2021-05-13. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ↑ Mishra SK, Tripathi T (February 2021). "One year update on the COVID-19 pandemic: Where are we now?". Acta Tropica. 214: 105778. doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2020.105778. PMC 7695590. PMID 33253656.

- ↑ Meo SA, Bukhari IA, Akram J, Meo AS, Klonoff DC (February 2021). "COVID-19 vaccines: comparison of biological, pharmacological characteristics and adverse effects of Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna Vaccines". European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 25 (3): 1663–1669. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202102_24877. PMID 33629336.

- ↑ VRBPAC mRNA-1273 Sponsor Briefing Document (PDF) (Report). Moderna. 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Jenco J (16 March 2021). "Moderna testing COVID-19 vaccine in children under 12". AAP News. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, Tyner HL, Yoon SK, Meece J, et al. (April 2021). "Interim Estimates of Vaccine Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccines in Preventing SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Health Care Personnel, First Responders, and Other Essential and Frontline Workers - Eight U.S. Locations, December 2020-March 2021" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 70 (13): 495–500. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e3. PMC 8022879. PMID 33793460. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Doria-Rose N, Suthar MS, Makowski M, O'Connell S, McDermott AB, Flach B, et al. (June 2021). "Antibody Persistence through 6 Months after the Second Dose of mRNA-1273 Vaccine for Covid-19". N Engl J Med. 384 (23): 2259–2261. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2103916. PMC 8524784. PMID 33822494.

- ↑ "Moderna says Covid vaccine durable for at least six months". France 24. Agence France-Presse. 5 August 2021. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "FDA Briefing Document: Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine". CDC Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee Meeting. 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Roberts PC, Makhene M, Coler RN, et al. (November 2020). "An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 - Preliminary Report". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (20): 1920–1931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022483. PMC 7377258. PMID 32663912.

- ↑ Hunziker P (24 July 2021). "Personalized-dose Covid-19 vaccination in a wave of virus Variants of Concern: Trading individual efficacy for societal benefit". Precision Nanomedicine. 4 (3): 805–820. doi:10.33218/001c.26101. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Hunziker P (7 March 2021). "Vaccination strategies for minimizing loss of life in Covid-19 in a Europe lacking vaccines". medRxiv: 2021.01.29.21250747. doi:10.1101/2021.01.29.21250747. S2CID 231729268. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Chen Z, Liu K, Liu X, Lou Y (February 2020). "Modelling epidemics with fractional-dose vaccination in response to limited vaccine supply". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 486: 110085. Bibcode:2020JThBi.48610085C. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2019.110085. PMID 31758966. S2CID 208254350.

- ↑ Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, et al. (July 2021). "Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection". Nature Medicine. 27 (7): 1205–1211. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. PMID 34002089. S2CID 234769053.

- ↑ Widge AT, Rouphael NG, Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Roberts PC, Makhene M, et al. (January 2021). "Durability of Responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 Vaccination". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (1): 80–82. doi:10.1056/nejmc2032195. PMC 7727324. PMID 33270381.

- ↑ Lumley SF, O'Donnell D, Stoesser NE, Matthews PC, Howarth A, Hatch SB, et al. (February 2021). "Antibody Status and Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Health Care Workers". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (6): 533–540. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2034545. PMC 7781098. PMID 33369366.

- ↑ "Additional Dose of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine for Patients Who Are Immunocompromised". CDC Advisory Board on Immunization Practices. 13 August 2020. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Krause P, Fleming TR, Longini I, Henao-Restrepo AM, Peto R (September 2020). "COVID-19 vaccine trials should seek worthwhile efficacy". Lancet. 396 (10253): 741–743. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31821-3. PMC 7832749. PMID 32861315.

WHO recommends that successful vaccines should show an estimated risk reduction of at least one-half, with sufficient precision to conclude that the true vaccine efficacy is greater than 30%. This means that the 95% CI for the trial result should exclude efficacy less than 30%. Current US Food and Drug Administration guidance includes this lower limit of 30% as a criterion for vaccine licensure.

- ↑ Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, et al. (May 2021). "Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection". Nature Medicine. Figure 3. 27 (7): 1205–1211. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 34002089. S2CID 234769053. Archived from the original on 2022-01-04. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Fowlkes A, Gaglani M, Groover K, Thiese MS, Tyner H, Ellingson K (27 August 2021). "Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccines in Preventing SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Frontline Workers Before and During B.1.617.2 (Delta) Variant Predominance — Eight U.S. Locations, December 2020–August 2021" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 70 (34): 1167–9. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7034e4. PMC 8389394. PMID 34437521. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Tang P, Hasan MR, Chemaitelly H, Yassine HM, Benslimane FM, Al Khatib HA, et al. (2 November 2021). "BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness against the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in Qatar". Nature Medicine. Tables 3 and 5. 27 (12): 2136–2143. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01583-4. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 34728831. S2CID 241108406. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Chung H, He S, Nasreen S, Sundaram ME, Buchan SA, Wilson SE, et al. (August 2021). "Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 covid-19 vaccines against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe covid-19 outcomes in Ontario, Canada: test negative design study". BMJ. eTables 6 and 7. 374: n1943. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1943. PMC 8377789. PMID 34417165.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ 65.0 65.1 "Vaccination Considerations for People Pregnant or Breastfeeding". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 18 March 2021. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ↑ Shimabukuro T (1 March 2021). "COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Update" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Smith K (24 April 2021). "New CDC guidance recommends pregnant people get the COVID-19 vaccine". CBS News. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ↑ Shimabukuro TT, Kim SY, Myers TR, Moro PL, Oduyebo T, Panagiotakopoulos L, et al. (June 2021). "Preliminary Findings of mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine Safety in Pregnant Persons". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (24): 2273–2282. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2104983. PMC 8117969. PMID 33882218.

- ↑ Weise E (7 April 2021). "COVID-19 toes, Moderna arm, all-body rash: Vaccines can cause skin reactions but aren't dangerous, study says". USA Today. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ CDC COVID-19 Response Team (January 2021). "Allergic Reactions Including Anaphylaxis After Receipt of the First Dose of Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 21, 2020-January 10, 2021" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 70 (4): 125–129. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7004e1. PMC 7842812. PMID 33507892. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ Blumenthal KG, Freeman EE, Saff RR, Robinson LB, Wolfson AR, Foreman RK, et al. (April 2021). "Delayed Large Local Reactions to mRNA-1273 Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2". The New England Journal of Medicine. 384 (13): 1273–1277. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2102131. PMC 7944952. PMID 33657292.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers Administering Vaccine (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Report). 12 August 2021. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ↑ National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (23 June 2021). "Myocarditis and Pericarditis Following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination". CDC.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Sweden, Denmark pause Moderna COVID-19 vaccine for younger age groups". Reuters. 6 October 2021. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ↑ "Finland joins Sweden and Denmark in limiting Moderna COVID-19 vaccine". Reuters. 7 October 2021. Archived from the original on 8 October 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- ↑ "Notkun COVID-19 bóluefnis Moderna á Íslandi" [Use of the COVID-19 vaccine Moderna in Iceland]. Directorate of Health of Iceland (in Icelandic). 8 October 2021. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ COVID-19 subcommittee of the WHO Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety (GACVS) (27 October 2021). "Updated statement regarding myocarditis and pericarditis reported with COVID-19 mRNA vaccines". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ↑ "Germany recommends only Biontech/Pfizer vaccine for people under 30". Reuters. 10 November 2021. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ↑ Cross R (29 September 2020). "The tiny tweak behind COVID-19 vaccines". Chemical & Engineering News. 98 (38). Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ Johnson CY (6 December 2020). "A gamble pays off in 'spectacular success': How the leading coronavirus vaccines made it to the finish line". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ↑ Kramer J (31 December 2020). "They spent 12 years solving a puzzle. It yielded the first COVID-19 vaccines". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Corbett KS, Edwards D, Leist SR, Abiona OM, Boyoglu-Barnum S, Gillespie RA, et al. (June 2020). "SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Development Enabled by Prototype Pathogen Preparedness". bioRxiv. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2622-0. PMC 7301911. PMID 32577634.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Auth DR, Powell MB (14 September 2020). "Patent Issues Highlight Risks of Moderna's COVID-19 Vaccine". New York Law Journal. Archived from the original on 15 October 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ "GenBank ID MN908947.3". National Center for Biotechnology Information. 18 March 2020. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 85.0 85.1 World Health Organization (June 2021). "INN Proposed International Nonproprietary Names: List 125 COVID-19 (special edition)" (PDF). WHO Drug Information. 35 (2): 578–9. hdl:10665/343367. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-24. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 86.3 Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Roberts PC, Makhene M, Coler RN, et al. (November 2020). "An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 - Preliminary Report". The New England Journal of Medicine. 383 (20): 1920–1931. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2022483. PMC 7377258. PMID 32663912.

- ↑ Jeong DE, McCoy M, Artiles K, Ilbay O, Fire A, Nadeau K, et al. (23 March 2021). "Assemblies of putative SARS-CoV2-spike-encoding mRNA sequences for vaccines BNT-162b2 and mRNA-1273". Virological.org. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Steenhuysen J, Kelland K (24 January 2020). "With Wuhan virus genetic code in hand, scientists begin work on a vaccine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ↑ Carey K (26 February 2020). "Increasing number of biopharma drugs target COVID-19 as virus spreads". BioWorld. Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ↑ Everett G (27 February 2020). "These 5 drug developers have jumped this week on hopes they can provide a coronavirus treatment". Markets Insider. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ↑ "Moderna Announces Expansion of BARDA Agreement to Support Larger Phase 3 Program for Vaccine (mRNA-1273) Against COVID-19". Moderna. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ↑ Grady D (16 November 2020). "Early Data Show Moderna's Coronavirus Vaccine Is 94.5% Effective". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ↑ "Dolly Parton 'honoured and proud' to help Covid-19 battle". BBC News. 18 November 2020. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ↑ Cohen E (30 November 2020). "Moderna applies for FDA authorization for its Covid-19 vaccine". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ Burger L (1 December 2020). "COVID-19 vaccine sprint as Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna seek emergency EU approval". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ Kuchler H (30 November 2020). "Canada could be among the first to clear Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine for use". The Financial Post. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ Parsons L (28 October 2020). "UK's MHRA starts rolling review of Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine". PharmaTimes. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 "Statement from NIH and BARDA on the FDA Emergency Use Authorization of the Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine". National Institutes of Health. 18 December 2020. Archived from the original on 19 March 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Lee J. "Moderna nears its first-ever FDA authorization, for its COVID-19 vaccine". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 16 April 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, Wallace M, Curran KG, Chamberland M, et al. (January 2021). "The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' Interim Recommendation for Use of Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 2020" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69 (5152): 1653–6. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm695152e1. PMID 33382675. S2CID 229945697. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-09. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Regulatory Decision Summary – Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine". Health Canada. 23 December 2020. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- ↑ "Israel authorises use of Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ↑ "Singapore becomes first in Asia to approve Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine". Reuters. 3 February 2021. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ↑ "WHO lists Moderna vaccine for emergency use". World Health Organization (WHO) (Press release). 30 April 2021. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 29 May 2021.

- ↑ "WHO lists anti-COVID Moderna vaccine for emergency use". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Agence France-Presse. 1 May 2021. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Lopez V (5 May 2021). "Philippines grants EUA to Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine". GMA News Online. Archived from the original on 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Kaul R (29 June 2021). "Moderna's Covid vaccine approved for use in India". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Nga L (29 June 2021). "Vietnam approves Moderna Covid vaccine for emergency use". VnExpress. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ↑ "NPRA Approves Moderna Covid-19 Vaccine". CodeBlue. 5 August 2021. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ↑ "EMA recommends COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna for authorisation in the EU" (Press release). European Medicines Agency (EMA). 6 January 2021. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2021.

- ↑ "COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna". Europa. Archived from the original on 2021-01-24. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ↑ "COVID-19 vaccine Spikevax approved for children aged 12 to 17 in EU". European Medicines Agency (EMA) (Press release). 23 July 2021. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Miller J (12 January 2021). "Swiss drugs regulator approves Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ↑ "Swissmedic grants authorisation for the COVID-19 vaccine from Moderna". Swissmedic (Press release). 12 January 2020. Archived from the original on 11 February 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ↑ "Pfizer, Moderna vaccines granted full approval by Health Canada; get name change". CityNews. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 116.2 116.3 Lovelace Jr B, Higgins-Dunn N (16 November 2020). "Moderna says preliminary trial data shows its coronavirus vaccine is more than 94% effective, shares soar". CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ Luthra S (23 November 2020). "Pregnant women haven't been included in promising COVID-19 vaccine trials". USA Today. Archived from the original on 3 December 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Krubiner C, Faden RR, Karron RA (9 December 2020). "FDA: Leave the door open to Covid-19 vaccination for pregnant and lactating health workers". STAT. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ McDonnell Nieto del Rio G (15 January 2021). "Covid-19: Over Two Million Around the World Have Died From the Virus". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ Tirrell M (14 January 2021). "Moderna looks to test Covid-19 booster shots a year after initial vaccination". CNBC. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ "Moderna Explores Whether Third Covid-19 Vaccine Dose Adds Extra Protection". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2021-01-15. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ "Japan's Takeda to import 50 million doses of Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine, raises profit forecast". Reuters. 29 October 2020. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ↑ "Takeda to supply Japan with Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine". European Pharmaceutical Review. 2 November 2020. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "Start of a Japanese Clinical Study of TAK-919, Moderna's COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate" (Press release). Takeda. 21 January 2021. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ↑ "Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine Update". 25 January 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 Grady D, Mandavilli A, Thomas K (25 January 2021). "Is the Covid-19 Vaccine Effective Against New South African Variant?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ↑ "Moderna Announces it has Shipped Variant-Specific Vaccine Candidate, mRNA-1273.351, to NIH for Clinical Study". Moderna Inc. (Press release). 24 February 2021. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ↑ Loftus P (16 March 2021). "Moderna Is Testing Its Covid-19 Vaccine on Young Children". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 16 March 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2021.

- ↑ "Moderna testing COVID-19 vaccine in children under 12". American Academy of Pediatrics. 16 March 2021. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "Moderna Reports Second Quarter Fiscal Year 2021 Financial Results and Provides Business Updates". Moderna, Inc. (Press release). 5 August 2021. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ↑ "A Study to Evaluate the Immunogenicity and Safety of mRNA-1273.211 Vaccine for COVID-19 Variants". ClinicalTrials.gov. 15 June 2021. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ↑ "Moderna Announces Positive Initial Booster Data Against SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern". Moderna, Inc. (Press release). 5 May 2021. Archived from the original on 2 December 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "EMA evaluating data on booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine Spikevax". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 27 September 2021. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ↑ "ECDC and EMA highlight considerations for additional booster doses of COVID-19 vaccines". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 2 September 2021. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ↑ "Comirnaty and Spikevax: EMA recommendations on extra doses boosters". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 4 October 2021. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 "CDC Expands Eligibility for COVID-19 Booster Shots". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 21 October 2021. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ 137.0 137.1 "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Expands Eligibility for COVID-19 Vaccine Boosters". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 19 November 2021. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Securing Singapore's access to COVID-19 vaccines". www.gov.sg. Singapore Government. 14 December 2020. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ Khalik S (1 February 2021). "How Singapore picked its Covid-19 vaccines". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ↑ "Trump says U.S. inks agreement with Moderna for 100 mln doses of COVID-19 vaccine candidate". Yahoo. Reuters. 11 August 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ↑ "Moderna aims to price coronavirus vaccine at $50–$60 per course: FT". Reuters. 28 July 2020. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ "Donald Trump appears to admit Covid is 'running wild' in the US". The Guardian. 22 November 2020. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

Moderna told the German weekly Welt am Sonntag that it will charge governments between $25 and $37 per dose of its Covid vaccine candidate, depending on the amount ordered.

- ↑ Guarascio F (24 November 2020). "EU secures 160 million doses of Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Commission approves contract with Moderna to ensure access to a potential vaccine". European Commission. 25 November 2020. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ "New agreements to secure additional vaccine candidates for COVID-19". Prime Minister's Office, Government of Canada. 25 September 2020. Archived from the original on 19 December 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ↑ Stevis-Gridneff M, Sanger-Katz M, Weiland N (18 December 2020). "A European Official Reveals a Secret: The U.S. Is Paying More for Coronavirus Vaccines". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ↑ Maddipatla M, Mishra M (25 February 2021). "Moderna sees $18.4 billion in sales from COVID-19 vaccine in 2021". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ↑ Springer P (24 May 2021). "Fargo firm makes key ingredient for millions of COVID-19 vaccine doses". Grand Forks Herald. Archived from the original on 22 August 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ 149.0 149.1 Mullin R (25 November 2020). "Pfizer, Moderna ready vaccine manufacturing networks". Chemical & Engineering News. American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 11 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ↑ Cote J (4 May 2021). "Moderna to more than double size of Massachusetts facility, transform production and lab space to industrial tech center". MassLive. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Hopkins JS (6 April 2021). "Moderna Covid-19 Vaccine Production Pace to Increase at Contract Manufacturer Catalent". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ↑ Loftus P (21 March 2021). "Covid-19 Vaccine Manufacturing in U.S. Races Ahead". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ↑ Williams J (29 April 2021). "Moderna doubling COVID-19 vaccine production". The Hill. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ↑ Loftus P (29 April 2021). "Moderna to Boost Covid-19 Vaccine Production to Meet Rising Global Demand". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ↑ "Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine Vaccination Storage & Dry Ice Safety Handling". Pfizer. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ↑ McGregor G (5 December 2020). "How China's COVID-19 could fill the gaps left by Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca". Fortune. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ↑ "Pfizer's Vaccine Is Out of the Question as Indonesia Lacks Refrigerators: State Pharma Boss". Jakarta Globe. 22 November 2020. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Allows More Flexible Storage, Transportation Conditions for Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 25 February 2021. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Pfizer and BioNTech Submit COVID-19 Vaccine Stability Data at Standard Freezer Temperature to the U.S. FDA". Pfizer (Press release). 19 February 2021. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ↑ "Storage & Handling". Moderna. 11 August 2021. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ↑ Dolgin E (November 2020). "COVID-19 vaccines poised for launch, but impact on pandemic unclear". Nature Biotechnology. doi:10.1038/d41587-020-00022-y. PMID 33239758. S2CID 227176634.

- ↑ Vardi N (29 June 2020). "Moderna's Mysterious Coronavirus Vaccine Delivery System". Forbes. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ "Moderna loses key patent challenge". Nature Biotechnology. 38 (9): 1009. September 2020. doi:10.1038/s41587-020-0674-1. PMID 32887970. S2CID 221504018.

- ↑ Hiltzik M (19 May 2020). "Column: Moderna's vaccine results boosted its share offering – and it's hardly a coincidence". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ Branswell H (19 May 2020). "Vaccine experts say Moderna didn't produce data critical to assessing Covid-19 vaccine". Stat. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ Taylor M, Respaut R (7 July 2020). "Exclusive: Moderna spars with U.S. scientists over COVID-19 vaccine trials". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ↑ "Moderna vaccine trial contractors fail to enroll enough people of color, prompting slowdown". NBC News. Reuters. 6 October 2020. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ↑ "Joint Statement from HHS Public Health and Medical Experts on COVID-19 Booster Shots" (Press release). United States Department of Health and Human Services. 18 August 2021. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ↑ Kramer J (18 August 2021). "The U.S. plans to authorize boosters—but many already got a third dose". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

Getting a booster too soon after primary inoculation might not teach the body’s immune system to mount a more robust defense

- ↑ Mendez R (26 August 2021). "Japan suspends 1.6 million Moderna Covid vaccine doses over contamination concerns". CNBC. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ↑ Lee J (14 May 2021). "Do Videos Show Magnets Sticking to People's Arms After COVID-19 Vaccine?". Snopes.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ↑ Fichera A (14 May 2021). "Magnet Videos Refuel Bogus Claim of Vaccine Microchips". FactCheck.org. Annenberg Public Policy Center. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ↑ "COVID-19 VACCINE MYTHS AND FACTS" (PDF). Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 August 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ↑ "COVID-19 Vaccine Facts". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 18 August 2021. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ↑ Dan Evon (2 November 2021). "'Luciferase' Is Not an Ingredient in COVID-19 Vaccines". Snopes.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "Fact Check-Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine does not contain luciferin or luciferase". Reuters. 6 May 2021. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "First Participants Dosed in Phase 1 Study Evaluating mRNA-1283, Moderna's Next Generation COVID-19 Vaccine" (Press release). Moderna. 15 March 2021. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022 – via Business Wire.

- ↑ "Moderna begins testing next-generation coronavirus vaccine". Reuters. 15 March 2021. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2021.

- ↑ "NIH clinical trial of investigational vaccine for COVID-19 begins". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 16 March 2020. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ↑ Kuznia R, Polglase K, Mezzofiore G (1 May 2020). "In quest for vaccine, US makes 'big bet' on company with unproven technology". CNN. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ↑ Keown A (7 May 2020). "Moderna moves into Phase II testing of COVID-19 vaccine candidate". BioSpace. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ↑ Blankenship K (1 May 2020). "Moderna aims for a billion COVID-19 shots a year with Lonza manufacturing tie-up". Fierce Pharma. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020.

- ↑ "Swiss factory rushes to prepare for Moderna Covid-19 vaccine". SWI swissinfo.ch. 7 October 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT04405076 for "Dose-Confirmation Study to Evaluate the Safety, Reactogenicity, and Immunogenicity of mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccine in Adults Aged 18 Years and Older" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Li Y (14 July 2020). "Dow futures jump more than 200 points after Moderna says its vaccine produces antibodies to coronavirus". CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ↑ 186.0 186.1 Herper M, Garde D (14 July 2020). "First data for Moderna Covid-19 vaccine show it spurs an immune response". Stat. Boston Globe Media. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ↑ Mateus J, Dan JM, Zhang Z, Moderbacher CR, Lammers M, Goodwin B, et al. (2021). "Low-dose mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine generates durable memory enhanced by cross-reactive T cells". Science. 374 (6566): eabj9853. doi:10.1126/science.abj9853. PMC 8542617. PMID 34519540.

- ↑ Bryant, Erin (5 October 2021). "Moderna COVID-19 vaccine generates long-lasting immune memory". NIH Research Matters. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 10 November 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ↑ Palca J (27 July 2020). "COVID-19 vaccine candidate heads to widespread testing in U.S." NPR. Archived from the original on 11 October 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ↑ Pagliarulo N, ed. (17 September 2020). "Moderna, in bid for transparency, discloses detailed plan of coronavirus vaccine trial". BioPharma Dive. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ↑ Mascarenhas L (1 October 2020). "Moderna chief says Covid-19 vaccine could be widely available by late March". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ Cohen E. "First large-scale US Covid-19 vaccine trial reaches target of 30,000 participants". CNN. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "Promising Interim Results from Clinical Trial of NIH-Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine". National Institutes of Health (NIH). 15 November 2020. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "Moderna Use Roche Antibody Test During Vaccine Trials". rapidmicrobiology.com. 10 December 2020. Archived from the original on 14 December 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ↑ Zimmer C (20 November 2020). "2 Companies Say Their Vaccines Are 95% Effective. What Does That Mean? You might assume that 95 out of every 100 people vaccinated will be protected from Covid-19. But that's not how the math works". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT04470427 for "A Study to Evaluate Efficacy, Safety, and Immunogenicity of mRNA-1273 Vaccine in Adults Aged 18 Years and Older to Prevent COVID-19" at ClinicalTrials.gov

External links

- "Elasomeran". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- "VRBPAC mRNA-1273 Sponsor Briefing Document" (PDF). Moderna. 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- "Clinical Study Protocol mRNA-1273-P301" (PDF). Moderna. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-09-28. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- "COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna assessment report" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-04-25. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- "How Moderna's Vaccine Works". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2021-05-07. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- "Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 6 August 2021. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- "Spikevax (previously COVID-19 Vaccine Moderna) Safety Updates". European Medicines Agency (EMA). Archived from the original on 2021-06-28. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- Australian Public Assessment Report for Elasomeran (PDF) (Report). Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). September 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-06. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- Dickerman BA, Gerlovin H, Madenci AL, Kurgansky KE, Ferolito BR, Figueroa Muñiz MJ, et al. (December 2021). "Comparative Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 Vaccines in U.S. Veterans". New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/nejmoa2115463. PMC 8693691. PMID 34942066.

- World Health Organization (2021). Background document on the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna) against COVID-19: background document to the WHO Interim recommendations for use of the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna), 3 February 2021 (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/339218. WHO/2019-nCoV/vaccines/SAGE_recommendation/mRNA-1273/background/2021.1.

| Identifiers: |

|

|---|

- Pages using duplicate arguments in template calls

- Pages with obsolete Vega graphs

- Pages with graphs

- Pages with non-numeric formatnum arguments

- CS1 maint: url-status

- CS1 maint: unrecognized language

- CS1 maint: archived copy as title

- Wikipedia articles incorporating the PD-notice template

- CS1 errors: dates

- CS1 maint: location

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- Articles with hatnote templates targeting a nonexistent page

- Missing redirects

- Drugs with non-standard legal status

- Chemical articles with unknown parameter in Infobox drug