Congenital hypothyroidism

| Congenital hypothyroidism | |

|---|---|

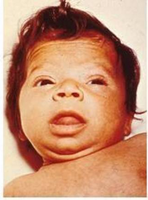

| Other names: Hypothyroidism in the newborn, cretinism[1] | |

| |

| 6 week old female with jaundice due to hypothyroidism | |

| Specialty | Endocrinology |

| Symptoms | Initially: Often none[2] Over weeks: Jaundice, poor feeding, constipation, poor cry, low body temperature, poor muscle tone[2] |

| Complications | Intellectual disability, short stature[3] |

| Usual onset | At birth[2] |

| Types | Endemic, sporadic[4] |

| Causes | Lack of a thyroid gland, iodine deficiency, genetic mutations[5][3] |

| Risk factors | Prematurity[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Newborn screening[2] |

| Treatment | Levothyroxine[2] |

| Prognosis | Excellent with early treatment[2] |

| Frequency | 1 in 2,000 newborns[2] |

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) is thyroid hormone deficiency present at birth.[2] Initially the baby may appear normal.[2] Without treatment, over the next few weeks to months, jaundice, poor feeding, constipation, poor or hoarse cry, low body temperature, and poor muscle tone may occur.[2] If treatment still dose not occur puffy eyes, large tongue, swollen abdomen, breathing problems, and intellectual disability may occur.[2][3]

Causes include lack of a thyroid gland, iodine deficiency, and genetic mutations involving the thyroglobulin gene, thyroid peroxidase gene, or thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptor.[5][6] Risk factors include prematurity.[2] Onset of symptoms is related to no further exposure to the mother's thyroid hormone after birth.[7] The condition is screened for at birth in most countries, by measuring either TSH or T4 around the third days of life.[2]

Treatment is with levothyroxine, as soon as the diagnosis is established.[2] The pills can be crushed and mixed with a small amount of breast milk.[2] Thyroid testing is than carried out every two weeks until the TSH is normal and than every 1 to 3 months until the child is one.[2] Most children with proper treatment develop normally.[8]

Congenital hypothyroidism occurs in about 1 in 2,000 newborns.[2] Females are more commonly affected than males.[2] Before newborn screening programs, it was one of the most common preventable causes of intellectual disability.[2] The connection between goiter and congenital iodine deficiency syndrome was determined by Paracelsus in the 1500s.[9] Effective treatment was found in 1891 by Murray in the form of thyroid extract.[10]

Signs and symptoms

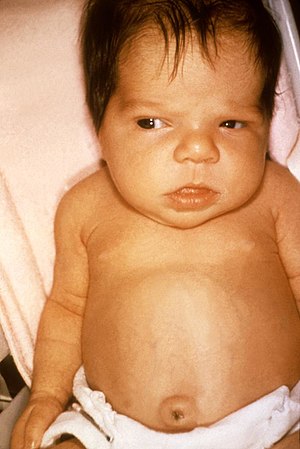

Infants born with congenital hypothyroidism may show no effects, or may display mild effects that go unrecognized: excessive sleeping, reduced interest in nursing, poor muscle tone, low or hoarse cry, infrequent bowel movements, significant jaundice, and low body temperature. If the fetal thyroid hormone deficiency is severe because of complete absence (athyreosis) of the gland, physical features may include a larger anterior fontanel, persistence of a posterior fontanel, an umbilical hernia, and a large tongue (macroglossia).[11]

In the era before newborn screening, less than half of cases of severe hypothyroidism were recognized in the first month of life. As the months proceeded, these babies would grow poorly and be delayed in their development. By several years of age, they would display the recognizable facial and body features of cretinism. Persistence of severe, untreated hypothyroidism resulted in severe mental impairment, with an IQ below 80 in the majority. Most of these children eventually ended up in institutional care.[11]

-

3-month-old infant with untreated CH; picture demonstrates hypotonic posture, myxedematous facies, macroglossia, and umbilical hernia

-

Close up of face, showing myxedematous facies, macroglossia, and skin mottling

-

Close up showing abdominal distension and umbilical hernia.

Cause

Around the world, the most common cause of congenital hypothyroidism is iodine deficiency, but in most of the developed world and areas of adequate environmental iodine, cases are due to a combination of known and unknown causes. Most commonly there is a defect of development of the thyroid gland itself, resulting in an absent (athyreosis) or underdeveloped (hypoplastic) gland. Cases may also occur with the gland in situ (termed dyshormonogenesis when there is a defect in hormone production).[12]

A hypoplastic gland may develop higher in the neck or even in the back of the tongue. A gland in the wrong place is referred to as ectopic, and an ectopic gland at the base or back of the tongue is a lingual thyroid. Some of these cases of developmentally abnormal glands result from genetic defects, and some are "sporadic," with no identifiable cause. One study found a correlation between certain organochlorine insecticides and dioxin-like chemicals in the milk of mothers who had given birth to infants with congenital hypothyroidism.[13] Neonatal hypothyroidism has been reported in cases of infants exposed to lithium, a mood stabilizer used to treat bipolar disorder, in utero.[14]

In some instances, hypothyroidism detected by screening may be transient. One common cause of this is the presence of maternal antibodies that temporarily impair thyroid function for several weeks.[15]

Iodine deficiency

The word "cretinism" is an old term for the state of mental and physical retardation resulting from untreated congenital hypothyroidism.[16] It was historically usually due to iodine deficiency because of low iodine levels in the soil and local food sources. The term acquired pejorative connotations as it became used in lay speech. It is now deprecated; ICD-10 uses "congenital iodine deficiency syndrome" with additional specifiers for the various types.[citation needed]

Genetics

Congenital hypothyroidism can also occur due to genetic defects of thyroxine or triiodothyronine synthesis within a structurally normal gland. Among specific defects are thyrotropin (TSH) resistance, iodine trapping defect, organification defect, thyroglobulin, and iodotyrosine deiodinase deficiency. In a small proportion of cases of congenital hypothyroidism, the defect is due to a deficiency of thyroid-stimulating hormone, either isolated or as part of congenital hypopituitarism.[17] Genetic types of nongoitrous congenital hypothyroidism include:

| OMIM | Name | Gene |

|---|---|---|

| 275200 | congenital hypothyroidism, nongoitrous 1 CHNG1 | TSHR |

| 218700 | CHNG2 | PAX8 |

| 609893 | CHNG3 | ? at 15q25.3-q26.1 |

| 275100 | CHNG4 | TSHB |

| 225250 | CHNG5 | NKX2-5 |

Nongoitrous congenital hypothyroidism has been described as the "most prevalent inborn endocrine disorder".[18]

Diagnosis

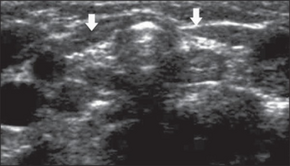

In the developed world, nearly all cases of congenital hypothyroidism are detected by the newborn screening program. These are based on measurement of TSH or thyroxine (T4) on the second or third day of life (Heel prick).[11]

Evaluation

If the TSH is high, or the T4 low, the infant's doctor and parents are called and a referral to a pediatric endocrinologist is recommended to confirm the diagnosis and initiate treatment. A technetium (Tc-99m pertechnetate) thyroid scan detects a structurally abnormal gland, while a radioactive iodine (RAIU) exam identifies congenital absence or a defect in organification (a process necessary to make thyroid hormone).[citation needed]

Treatment

The goal of newborn screening programs is to detect and start treatment within the first 1–2 weeks of life. Treatment consists of a daily dose of thyroxine, available as a small tablet. The generic name is levothyroxine, and several brands are available. The tablet is crushed and given to the baby with a small amount of water or milk. The most commonly recommended dose range is 10-15 μg/kg daily, typically 12.5 to 37.5 or 44 μg.[19] Within a few weeks, the T4 and TSH levels are rechecked to confirm that they are being normalized by treatment. As the child grows up, these levels are checked regularly to maintain the right dose. The dose increases as the child grow.[citation needed]

Prognosis

Most children born with congenital hypothyroidism and correctly treated with thyroxine grow and develop normally in all respects. Even most of those with athyreosis and undetectable T4 levels at birth develop with normal intelligence, although as a population academic performance tends to be below that of siblings and mild learning problems occur in some.[20]

Congenital hypothyroidism is the most common preventable cause of intellectual disability. Few treatments in the practice of medicine provide as large a benefit for as small an effort. The developmental quotient (DQ, as per Gesell Developmental Schedules) of children with hypothyroidism at age 24 months that have received treatment within the first 3 weeks of birth is summarised below:[citation needed]

| . | Adaptive behavior | Fine motor | Gross motor | Language | Personal-social behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe CH | 92 | 89 | 90 | 89 | 90 |

| Moderate CH | 97 | 97 | 98 | 96 | 96 |

| Mild CH | 100 | 99 | 100 | 99 | 100 |

Epidemiology

Congenital hypothyroidism (CH) occurs in 1:1300 to 1:4000 births worldwide.[12][22][23][24][25] The differences in CH-incidence are more likely due to iodine deficiency thyroid disorders or to the type of screening method than to ethnic affiliation.[22] CH is caused by an absent or defective thyroid gland classified into agenesis (22-42%), ectopy (35-42%) and gland in place defects (24-36%).[22][26] It is also found to be of increased association with female sex and gestational age >40 weeks.[26]

References

- ↑ "Hypothyroidism - Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 Bowden, SA; Goldis, M (January 2022). "Congenital Hypothyroidism". PMID 32644339.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Hypothyroidism in the Newborn - Children's Health Issues". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ↑ Chen, ZP; Hetzel, BS (February 2010). "Cretinism revisited". Best practice & research. Clinical endocrinology & metabolism. 24 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2009.08.014. PMID 20172469.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 James, William D.; Elston, Dirk; Treat, James R.; Rosenbach, Misha A.; Neuhaus, Isaac (2020). "24. Endocrine diseases". Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (13th ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-323-54753-6. Archived from the original on 2022-06-14. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- ↑ "Hypothyroidism in Infants and Children - Children's Health Issues". MSD Manual Consumer Version. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ↑ Kaye, Celia I. (1 September 2006). "Newborn Screening Fact Sheets" (PDF). Pediatrics. 118 (3): e934–e963. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-1783. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ↑ Cherella, CE; Wassner, AJ (February 2020). "Update on congenital hypothyroidism". Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity. 27 (1): 63–69. doi:10.1097/MED.0000000000000520. PMID 31789720.

- ↑ Wass, John; Arlt, Wiebke; Semple, Robert (10 March 2022). Oxford Textbook of Endocrinology and Diabetes 3e. Oxford University Press. p. 974. ISBN 978-0-19-252328-0. Archived from the original on 23 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ↑ Brown, Rosalind S.; Demmer, Laurie A. (September 2002). "The Etiology of Thyroid Dysgenesis—Still an Enigma after All These Years". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 87 (9): 4069–4071. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021092.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Hypothyroidism". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Archived from the original on 27 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Worth, Chris; Hird, Beverly; Tetlow, Lesley; Wright, Neville; Patel, Leena; Banerjee, Indraneel (14 November 2019). "Thyroid scintigraphy differentiates subtypes of congenital hypothyroidism". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 106 (1): archdischild-2019-317665. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2019-317665. PMID 31727620. S2CID 208039220. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ↑ Nagayama J, Kohno H, Kunisue T, et al. (2007). "Concentrations of organochlorine pollutants in mothers who gave birth to neonates with congenital hypothyroidism". Chemosphere. 68 (5): 972–6. Bibcode:2007Chmsp..68..972N. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.01.010. PMID 17307219.

- ↑ Frassetto, F; Tourneur Martel, F; Barjhoux, CE; Villier, C; Bot, BL; Vincent, F (November 2002). "Goiter in a newborn exposed to lithium in utero". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (11): 1745–8. doi:10.1345/aph.1C123. PMID 12398572. S2CID 24175902.

- ↑ "Congenital hypothyroidism". Orphanet. August 2010. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ↑ Salisbury, S (February 2003). "Cretinism: The past, present and future of diagnosis and cure". Paediatrics & child health. 8 (2): 105–6. doi:10.1093/pch/8.2.105. PMID 20019927.

- ↑ "Hypopituitarism". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- ↑ Grasberger H, Vaxillaire M, Pannain S, et al. (December 2005). "Identification of a locus for nongoitrous congenital hypothyroidism on chromosome 15q25.3-26.1". Hum. Genet. 118 (3–4): 348–55. doi:10.1007/s00439-005-0036-6. PMID 16189712. S2CID 19782628.

- ↑ LaFranchi SH, Austin J (2007). "How should we be treating children with congenital hypothyroidism?". J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 20 (5): 559–78. doi:10.1515/JPEM.2007.20.5.559. PMID 17642417. S2CID 638254.

- ↑ Moltz KC, Postellon DC (1994). "Congenital hypothyroidism and mental development". Compr Ther. 20 (6): 342–6. PMID 8062543.

- ↑ Huo K, Zhang Z, Zhao D, Li H, Wang J, Wang X, Feng H, Wang X, Zhu C (2011). "Risk factors for neurodevelopmental deficits in congenital hypothyroidism after early substitution treatment". Endocrine Journal. 58 (5): 355–61. doi:10.1507/endocrj.k10e-384. PMID 21467693.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Klett, M (1997). "Epidemiology of congenital hypothyroidism". Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes. 105 Suppl 4: 19–23. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1211926. PMID 9439909.

- ↑ Harris, KB; Pass, KA (July 2007). "Increase in congenital hypothyroidism in New York State and in the United States". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 91 (3): 268–77. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.03.012. PMID 17512233.

- ↑ Deladoey, J.; Belanger, N.; Van Vliet, G. (1 August 2007). "Random Variability in Congenital Hypothyroidism from Thyroid Dysgenesis over 16 Years in Quebec". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 92 (8): 3158–3161. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-0527. PMID 17504897.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Olney, RS; Grosse, SD; Vogt RF, Jr (May 2010). "Prevalence of congenital hypothyroidism--current trends and future directions: workshop summary". Pediatrics. 125 Suppl 2: S31-6. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1975C. PMID 20435715. Archived from the original on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Medda, E; Olivieri, A; Stazi, MA; Grandolfo, ME; Fazzini, C; Baserga, M; Burroni, M; Cacciari, E; Calaciura, F; Cassio, A; Chiovato, L; Costa, P; Leonardi, D; Martucci, M; Moschini, L; Pagliardini, S; Parlato, G; Pignero, A; Pinchera, A; Sala, D; Sava, L; Stoppioni, V; Tancredi, F; Valentini, F; Vigneri, R; Sorcini, M (December 2005). "Risk factors for congenital hypothyroidism: results of a population case-control study (1997–2003)". European Journal of Endocrinology. 153 (6): 765–73. doi:10.1530/eje.1.02048. PMID 16322381.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 errors: missing periodical

- CS1: long volume value

- CS1 maint: url-status

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from August 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Thyroid disease

- Congenital disorders of endocrine system

- Intellectual disability

- Cell surface receptor deficiencies

- RTT