Currarino syndrome

| Currarino syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Currarino triad | |

| |

| An X-ray showing Imperforate anus | |

The Currarino syndrome is an inherited congenital disorder where either the sacrum (the fused vertebrae forming the back of the pelvis) is not formed properly, or there is a mass in the presacral space in front of the sacrum, and there are malformations of the anus or rectum. It occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 people.[1]

Anterior sacral meningocele is the most common presacral mass in patients with Currarino syndrome occurring in 60% of cases. Its presence may significantly affect the surgical management of these patients.[2][3] Other potential presacral masses include presacral teratoma and enteric cyst. Presacral teratoma usually is considered to be a variant of sacrococcygeal teratoma. However, the presacral teratoma that is characteristic of the Currarino syndrome may be a distinct kind.[4]

Symptoms and signs

The clinical presentation of this condition is as follows:[5]

- Arteriovenous malformation

- Bifid scrotum

- Underdeveloped penis

- Lower limb asymmetry

- Vesicoureteral reflux

Genetics

The disorder is an autosomal dominant genetic trait[6] caused by a mutation in the HLXB9 homeobox gene. In 2000 the first large series of Currarino cases was genetically screened for HLXB9 mutations, and it was shown that the gene is specifically causative for the syndrome, but not for other forms of sacral agenesis. The study was published in the American Journal of Human Genetics.[7]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of Currarino syndrome is usually clinical, detecting all three elements of the triad. However, genetic testing is often used as the confirmation of diagnosis and genetic analysis of patient's family members.[8][9]

Treatment

Surgery of an anterior myelomeningocele is not necessarily indicated, only in the rare case in which the space-occupying aspect is expected to cause constipation or problems during pregnancy or delivery. Fistulas between the spinal canal and colon have to be operated on directly.[10]

Importance of early diagnosis and multidisciplinary assessment is recommended to establish adequate treatment if needed.[11][12][13]

By accurate evaluation, the correct surgical management, including neurosurgery, can be performed in a 1-stage approach.[14]

The management of Currarino syndrome is similar to the usual management of anorectal malformation (ARM) regarding the surgical approach and probably the prognosis that mainly depends on degree of associated sacral dysplasia.[15]

The cooperation between pediatric surgeons and neurosurgeons is crucial. The follow-up of these patients should be done in a spina bifida clinic.[16]

Neurosurgeons are involved in the surgical treatment of anterior meningoceles, which are often associated with this condition. The accepted surgical treatment is an anterior or posterior or a staged anterior-posterior resection of the presacral mass and obliteration of the anterior meningocele.[17][18]

The anterior sacral meningocele regresses over time following transdural ligation of its neck.[19]

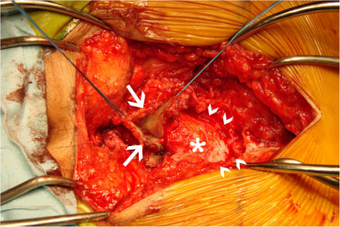

Posterior approach

A posterior procedure via lumbar and sacral partial laminectomy-laminoplasty and transdural ligation of the neck of the meningocele for anterior sacral meningoceles, or alternatively, tumor excision for other types of presacral lesions.[20][21]

Endoscopic or endoscope-assisted surgery via a posterior sacral route can be feasible for treatment of some of the patients with anterior sacral meningocele. Anterior meningocele pouch associated with Currarino syndrome will regresses over time following transdural ligation of its neck.[22]

Anterior approach

A 40-year-old woman presenting with cauda equina syndrome and ascending meningitis. The meningocele was removed using an anterior abdominal approach. A sigmoid resection was performed with rectal on-table antegrade lavage followed by closure of the rectal fistula, closure of the rectal stump, and proximal colostomy. Closure of the sacral deficit was carried out by suturing a strip of well-vascularized omentum and fibrin glue[citation needed]

Prompt surgical management using an anterior approach, resection of the sac, closure of the sacral deficit, and fecal diversion resulted in a satisfactory outcome.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ Weber, Stefanie; Dávila, Magdalena (2014). "German approach of coding rare diseases with ICD-10-GM and Orpha numbers in routine settings". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 9 (Suppl 1): O10. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-9-s1-o10. ISSN 1750-1172.

- ↑ Emans, Pieter J.; van Aalst, Jasper; van Heurn, Ernest L.W.; Marcelis, Carlo; Kootstra, Gauke; Beets-Tan, Regina G.H.; Vles, Johannes S.H.; Beuls, Emile A.M. (2006-05-01). "The Currarino Triad: Neurosurgical Considerations". Neurosurgery. 58 (5): 924–929. doi:10.1227/01.neu.0000209945.87233.6a. ISSN 0148-396X. PMID 16639328. S2CID 45316326.

- ↑ Samuel, M.; Hosie, G.; Holmes, K. (December 2000). "Currarino triad—Diagnostic dilemma and a combined surgical approach". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 35 (12): 1790–1794. doi:10.1053/jpsu.2000.19258. ISSN 0022-3468. PMID 11101738.

- ↑ Gopal M, Turnpenny PD, Spicer R (June 2007). "Hereditary sacrococcygeal teratoma--not the same as its sporadic counterpart!". Eur J Pediatr Surg. 17 (3): 214–6. doi:10.1055/s-2007-965121. PMID 17638164.

- ↑ "Currarino triad | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- ↑ Ashcraft KW; Holder TM (October 1974). "Hereditary presacral teratoma". J. Pediatr. Surg. 9 (5): 691–7. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(74)90107-9. PMID 4418917.

- ↑ Belloni, E; Martucciello, G; Verderio, D; Ponti, E; Seri, M; Jasonni, V; Torre, M; Ferrari, M; Tsui, LC; Scherer, SW (January 2000). "Involvement of the HLXB9 homeobox gene in Currarino syndrome". American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (1): 312–9. doi:10.1086/302723. PMC 1288336. PMID 10631160.

- ↑ AbouZeid, Amr Abdelhamid; Mohammad, Shaimaa Abdelsattar; Abolfotoh, Mohammad; Radwan, Ahmed Bassiouny; Ismail, Mohamed Mohamed ElSayed; Hassan, Tarek Ahmed (August 2017). "The Currarino triad: What pediatric surgeons need to know". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 52 (8): 1260–1268. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.12.010. PMID 28065719.

- ↑ Garcia-Barceló, Mercè; So, Man-ting; Lau, Danny Ko-chun; Leon, Thomas Yuk-yu; Yuan, Zheng-wei; Cai, Wei-song; Lui, Vincent Chi-hang; Fu, Ming; Herbrick, Jo-Anne; Gutter, Emily; Proud, Virginia (2006-01-01). "Population Differences in the Polyalanine Domain and 6 New Mutations in HLXB9 in Patients with Currarino Syndrome". Clinical Chemistry. 52 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2005.056192. ISSN 0009-9147. PMID 16254195. Archived from the original on 2021-08-28. Retrieved 2021-01-28.

- ↑ Emans PJ, van Aalst J, van Heurn EL, Marcelis C, Kootstra G, Beets-Tan RG, Vles JS, Beuls EA (2006). "The Currarino triad: neurosurgical considerations". Neurosurgery. 58 (5): 924–9, discussion 924–9. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000209945.87233.6A. PMID 16639328. S2CID 45316326.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Berghauser Pont LM, Dirven CM, Dammers R (2012). "Currarino's triad diagnosed in an adult woman". Eur Spine J. 21 Suppl 4: S569-72. doi:10.1007/s00586-012-2311-2. PMC 3369045. PMID 22526704.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Emoto S, Kaneko M, Murono K, Sasaki K, Otani K, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Hata K, Kawai K, Imai H, Saito N, Kobayashi H, Tanaka S, Ikemura M, Ushiku T, Nozawa H (2018). "Surgical management for a huge presacral teratoma and a meningocele in an adult with Currarino triad: a case report". Surg Case Rep. 4 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/s40792-018-0419-2. PMC 5775187. PMID 29352751.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Samuel M, Hosie G, Holmes K (Dec 2000). "Currarino triad--diagnostic dilemma and a combined surgical approach". J Pediatr Surg. 35 (12): 1790–4. doi:10.1053/jpsu.2000.19258. PMID 11101738.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Crétolle C, Zérah M, Jaubert F, Sarnacki S, Révillon Y, Lyonnet S, Nihoul-Fékété C (2006). "New clinical and therapeutic perspectives in Currarino syndrome (study of 29 cases)". J Pediatr Surg. 41 (1): 126–31, discussion 126–31. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.10.053. PMID 16410121.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ AbouZeid AA, Mohammad SA, Abolfotoh M, Radwan AB, Ismail MME, Hassan TA (2017). "The Currarino triad: What pediatric surgeons need to know". J Pediatr Surg. 52 (8): 1260–1268. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.12.010. PMID 28065719.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Serratrice N, Fievet L, Albader F, Scavarda D, Dufour H, Fuentes S (2018). "Multiple neurosurgical treatments for different members of the same family with Currarino syndrome". Neurochirurgie. 64 (3): 211–215. doi:10.1016/j.neuchi.2018.01.009. PMID 29731315.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Chakhalian D, Gunasekaran A, Gandhi G, Bradley L, Mizell J, Kazemi N (2017). "Multidisciplinary surgical treatment of presacral meningocele and teratoma in an adult with Currarino triad". Surg Neurol Int. 8: 77. doi:10.4103/sni.sni_439_16. PMC 5445655. PMID 28584680.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Emoto S, Kaneko M, Murono K, Sasaki K, Otani K, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Hata K, Kawai K, Imai H, Saito N, Kobayashi H, Tanaka S, Ikemura M, Ushiku T, Nozawa H (2018). "Surgical management for a huge presacral teratoma and a meningocele in an adult with Currarino triad: a case report". Surg Case Rep. 4 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/s40792-018-0419-2. PMC 5775187. PMID 29352751.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Işik N, Balak N, Kircelli A, Göynümer G, Elmaci I (2008). "The shrinking of an anterior sacral meningocele in time following transdural ligation of its neck in a case of the Currarino triad". Turk Neurosurg. 18 (3): 254–8. PMID 18814114.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Isik N, Elmaci I, Gokben B, Balak N, Tosyali N (2010). "Currarino triad: surgical management and follow-up results of four [correction of three] cases". Pediatr Neurosurg. 46 (2): 110–9. doi:10.1159/000319007. PMID 20664237. S2CID 30203031.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kansal R, Mahore A, Dange N, Kukreja S (2012). "Epidermoid cyst inside anterior sacral meningocele in an adult patient of Currarino syndrome manifesting with meningitis". Turk Neurosurg. 22 (5): 659–61. doi:10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.3985-10.1. PMID 23015348.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Duru S, Karabagli H, Turkoglu E, Erşahin Y (2014). "Currarino syndrome: report of five consecutive patients". Childs Nerv Syst. 30 (3): 547–52. doi:10.1007/s00381-013-2274-6. PMID 24013264. S2CID 20214381.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Bergeron E, Roux A, Demers J, Vanier LE, Moore L (2010). "A 40-year-old woman with cauda equina syndrome caused by rectothecal fistula arising from an anterior sacral meningocele". Neurosurgery. 67 (5): E1464–7, discussion E1467–8. doi:10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181f352ba. PMID 20871432. S2CID 31090668.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- https://operativeneurosurgery.com/doku.php?id=currarino_syndrome_treatment Archived 2020-11-30 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pages with script errors

- CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list

- CS1: long volume value

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from November 2020

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Webarchive template wayback links

- Rare syndromes

- Congenital disorders of nervous system

- Autosomal dominant disorders

- Medical triads