Idiopathic intracranial hypertension

| Idiopathic intracranial hypertension | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Benign intracranial hypertension (BIH),[1] pseudotumor cerebri (PTC)[2] | |

| |

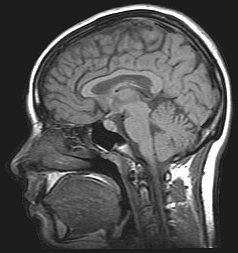

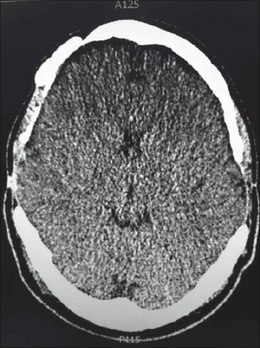

| For the diagnosis, brain scans (such as MRI) should be done to rule out other potential causes | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Headache, vision problems, ringing in the ears with the heartbeat[1][2] |

| Complications | Vision loss[2] |

| Usual onset | 20–50 years old[2] |

| Risk factors | Overweight, tetracycline[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, lumbar puncture, brain imaging[1][2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Brain tumor, arachnoiditis, meningitis[3] |

| Treatment | Healthy diet, salt restriction, exercise, surgery[2] |

| Medication | Acetazolamide[2] |

| Prognosis | Variable[2] |

| Frequency | 2 per 100,000 per year[4] |

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), previously known as pseudotumor cerebri and benign intracranial hypertension, is a condition characterized by increased intracranial pressure (pressure around the brain) without a detectable cause.[2] The main symptoms are headache, vision problems, ringing in the ears with the heartbeat, and shoulder pain.[1][2] Complications may include vision loss.[2]

Risk factors include being overweight or a recent increase in weight.[1] Tetracycline may also trigger the condition.[2] The diagnosis is based on symptoms and a high intracranial pressure found during a lumbar puncture with no specific cause found on a brain scan.[1][2]

Treatment includes a healthy diet, salt restriction, and exercise.[2] Bariatric surgery may also be used to help with weight loss.[2] The medication acetazolamide may also be used along with the above measures.[2] A small percentage of people may require surgery to relieve the pressure.[2]

About 2 per 100,000 people are newly affected per year.[4] The condition most commonly affects women aged 20–50.[2] Women are affected about 20 times more often than men.[2] The condition was first described in 1897.[1]

Signs and symptoms

The most common symptom of IIH is headache, which occurs in almost all (92–94%) cases. It is characteristically worse in the morning, generalized in character and throbbing in nature. It may be associated with nausea and vomiting. The headache can be made worse by any activity that further increases the intracranial pressure, such as coughing and sneezing. The pain may also be experienced in the neck and shoulders.[5] Many have pulsatile tinnitus, a whooshing sensation in one or both ears (64–87%); this sound is synchronous with the pulse.[5][6] Various other symptoms, such as numbness of the extremities, generalized weakness, loss of smell, and loss of coordination, are reported more rarely; none are specific for IIH.[5] In children, numerous nonspecific signs and symptoms may be present.[7]

The increased pressure leads to compression and traction of the cranial nerves, a group of nerves that arise from the brain stem and supply the face and neck. Most commonly, the abducens nerve (sixth nerve) is involved. This nerve supplies the muscle that pulls the eye outward. Those with sixth nerve palsy therefore experience horizontal double vision which is worse when looking towards the affected side. More rarely, the oculomotor nerve and trochlear nerve (third and fourth nerve palsy, respectively) are affected; both play a role in eye movements.[7][8] The facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve) is affected occasionally –- the result is total or partial weakness of the muscles of facial expression on one or both sides of the face.[5]

The increased pressure leads to papilledema, which is swelling of the optic disc, the spot where the optic nerve enters the eyeball. This occurs in practically all cases of IIH, but not everyone experiences symptoms from this. Those who do experience symptoms typically report "transient visual obscurations", episodes of difficulty seeing that occur in both eyes but not necessarily at the same time. Long-term untreated papilledema leads to visual loss, initially in the periphery but progressively towards the center of vision.[5][9]

Physical examination of the nervous system is typically normal apart from the presence of papilledema, which is seen on examination of the eye with a small device called an ophthalmoscope or in more detail with a fundus camera. If there are cranial nerve abnormalities, these may be noticed on eye examination in the form of a squint (third, fourth, or sixth nerve palsy) or as facial nerve palsy. If the papilledema has been longstanding, visual fields may be constricted and visual acuity may be decreased. Visual field testing by automated (Humphrey) perimetry is recommended as other methods of testing may be less accurate. Longstanding papilledema leads to optic atrophy, in which the disc looks pale and visual loss tends to be advanced.[5][9]

Causes

"Idiopathic" means of unknown cause. Therefore, IIH can only be diagnosed if there is no alternative explanation for the symptoms. Intracranial pressure may be increased due to medications such as high-dose vitamin A derivatives (e.g., isotretinoin for acne), long-term tetracycline antibiotics (for a variety of skin conditions) and hormonal contraceptives.

There are numerous other diseases, mostly rare conditions, that may lead to intracranial hypertension. If there is an underlying cause, the condition is termed "secondary intracranial hypertension".[5] Common causes of secondary intracranial hypertension include obstructive sleep apnea (a sleep-related breathing disorder), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), chronic kidney disease, and Behçet's disease.[9]

Mechanism

The cause of IIH is not known. The Monro–Kellie rule states that the intracranial pressure is determined by the amount of brain tissue, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood inside the bony cranial vault. Three theories therefore exist as to why the pressure might be raised in IIH: an excess of CSF production, increased volume of blood or brain tissue, or obstruction of the veins that drain blood from the brain.[5]

The first theory, that of increased production of cerebrospinal fluid, was proposed in early descriptions of the disease. However, there is no experimental data that supports a role for this process in IIH.[5]

The second theory posits that either increased blood flow to the brain or increase in the brain tissue itself may result in the raised pressure. Little evidence has accumulated to support the suggestion that increased blood flow plays a role, but recently Bateman et al. in phase contrast MRA studies have quantified cerebral blood flow (CBF) in vivo and suggests that CBF is abnormally elevated in many people with IIH. Both biopsy samples and various types of brain scans have shown an increased water content of the brain tissue. It remains unclear why this might be the case.[5]

The third theory suggests that restricted venous drainage from the brain may be impaired resulting in congestion. Many people with IIH have narrowing of the transverse sinuses.[10] It is not clear whether this narrowing is the pathogenesis of the disease or a secondary phenomenon. It has been proposed that a positive biofeedback loop may exist, where raised ICP (intracranial pressure) causes venous narrowing in the transverse sinuses, resulting in venous hypertension (raised venous pressure), decreased CSF resorption via arachnoid granulation and further rise in ICP.[11]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis may be suspected on the basis of the history and examination. To confirm the diagnosis, as well as excluding alternative causes, several investigations are required; more investigations may be performed if the history is not typical or the person is more likely to have an alternative problem: children, men, the elderly, or women who are not overweight.[8]

Investigations

Neuroimaging, usually with computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is used to exclude any mass lesions. In IIH these scans typically appear to be normal, although small or slit-like ventricles, dilatation and buckling[13] of the optic nerve sheaths and "empty sella sign" (flattening of the pituitary gland due to increased pressure) and enlargement of Meckel's caves may be seen.

An MR venogram is also performed in most cases to exclude the possibility of venous sinus stenosis/obstruction or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.[5][7][8] A contrast-enhanced MRV (ATECO) scan has a high detection rate for abnormal transverse sinus stenoses.[10] These stenoses can be more adequately identified and assessed with catheter cerebral venography and manometry.[11] Buckling of the bilateral optic nerves with increased perineural fluid is also often noted on MRI imaging.

Lumbar puncture is performed to measure the opening pressure, as well as to obtain cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to exclude alternative diagnoses. If the opening pressure is increased, CSF may be removed for transient relief (see below).[8] The CSF is examined for abnormal cells, infections, antibody levels, the glucose level, and protein levels. By definition, all of these are within their normal limits in IIH.[8] Occasionally, the CSF pressure measurement may be normal despite very suggestive symptoms. This may be attributable to the fact that CSF pressure may fluctuate over the course of the normal day. If the suspicion of problems remains high, it may be necessary to perform more long-term monitoring of the ICP by a pressure catheter.[8]

Classification

| Symptoms of increased ICP – CSF pressure >25 cmH2O |

| No localizing signs with the exception of 6th nerve palsy |

| Normal CSF composition |

| Normal to small (slit) ventricles on imaging with no intracranial mass |

The original criteria for IIH were described by Dandy in 1937.[14]

| Smptoms of raised intracranial pressure (headache, nausea, vomiting, transient visual obscurations, or papilledema) |

| No localizing signs with the exception of 6th nerve palsy |

| Person is awake and alert |

| Normal CT/MRI findings without evidence of thrombosis |

| LP opening pressure of >25 cmH2O and normal biochemisty and cytology of CSF |

| No other explanation for the raised intracranial pressure |

They were modified by Smith in 1985 to become the "modified Dandy criteria". Smith included the use of more advanced imaging: Dandy had required ventriculography, but Smith replaced this with computed tomography.[16] In a 2001 paper, Digre and Corbett amended Dandy's criteria further. They added the requirement that the person is awake and alert, as coma precludes adequate neurological assessment, and require exclusion of venous sinus thrombosis as an underlying cause. Furthermore, they added the requirement that no other cause for the raised ICP is found.[5][9][15]

In a 2002 review, Friedman and Jacobson propose an alternative set of criteria, derived from Smith's. These require the absence of symptoms that could not be explained by a diagnosis of IIH, but do not require the actual presence of any symptoms (such as headache) attributable to IIH. These criteria also require that the lumbar puncture is performed with the person lying sideways, as a lumbar puncture performed in the upright sitting position can lead to artificially high pressure measurements. Friedman and Jacobson also do not insist on MR venography for every person; rather, this is only required in atypical cases (see "diagnosis" above).[8]

Treatment

The primary goal in treatment of IIH is the prevention of visual loss and blindness, as well as symptom control.[9] IIH is treated mainly through the reduction of CSF pressure and, where applicable, weight loss. IIH may resolve after initial treatment, may go into spontaneous remission (although it can still relapse at a later stage), or may continue chronically.[5][8]

Lumbar puncture

The first step in symptom control is drainage of cerebrospinal fluid by lumbar puncture. If necessary, this may be performed at the same time as a diagnostic LP (such as done in search of a CSF infection). In some cases, this is sufficient to control the symptoms, and no further treatment is needed.[7][9]

The procedure can be repeated if necessary, but this is generally taken as a clue that additional treatments may be required to control the symptoms and preserve vision. Repeated lumbar punctures are regarded as unpleasant by people, and they present a danger of introducing spinal infections if done too often.[5][7] Repeated lumbar punctures are sometimes needed to control the ICP urgently if the person's vision deteriorates rapidly.[9]

Medication

The best-studied medical treatment for intracranial hypertension is acetazolamide (Diamox), which acts by inhibiting the enzyme carbonic anhydrase, and it reduces CSF production by six to 57 percent. It can cause the symptoms of hypokalemia (low blood potassium levels), which include muscle weakness and tingling in the fingers. Acetazolamide cannot be used in pregnancy, since it has been shown to cause embryonic abnormalities in animal studies. Also, in human beings it has been shown to cause metabolic acidosis as well as disruptions in the blood electrolyte levels of newborn babies. The diuretic furosemide is sometimes used for a treatment if acetazolamide is not tolerated, but this drug sometimes has little effect on the ICP.[5][9]

Various analgesics (painkillers) may be used in controlling the headaches of intracranial hypertension. In addition to conventional agents such as paracetamol, a low dose of the antidepressant amitriptyline or the anticonvulsant topiramate have shown some additional benefit for pain relief.[9]

The use of steroids in the attempt to reduce the ICP is controversial. These may be used in severe papilledema, but otherwise their use is discouraged.[5]

Venous sinus stenting

Venous sinus stenoses leading to venous hypertension appear to play a significant part in relation to raised ICP, and stenting of a transverse sinus may resolve venous hypertension, leading to improved CSF resorption, decreased ICP, cure of papilledema and other symptoms of IIH.[11]

A self-expanding metal stent is permanently deployed within the dominant transverse sinus across the stenosis under general anaesthesia. In general, people are discharged the next day. People require double antiplatelet therapy for a period of up to 3 months after the procedure and aspirin therapy for up to 1 year.

In a systematic analysis of 19 studies with 207 cases, there was an 87% improvement in overall symptom rate and 90% cure rate for treatment of papilledema. Major complications only occurred in 3/207 people (1.4%).[17] In the largest single series of transverse sinus stenting there was an 11% rate of recurrence after one stent, requiring further stenting.[11]

Due to the permanence of the stent and small but definite risk of complications, most experts will recommend that person with IIH must have papilledema and have failed medical therapy or are intolerant to medication before stenting is undertaken.

Surgery

Two main surgical procedures exist in the treatment of IIH: optic nerve sheath decompression and fenestration and shunting. Surgery would normally only be offered if medical therapy is either unsuccessful or not tolerated.[7][9] The choice between these two procedures depends on the predominant problem in IIH. Neither procedure is perfect: both may cause significant complications, and both may eventually fail in controlling the symptoms. There are no randomized controlled trials to guide the decision as to which procedure is best.[9]

Optic nerve sheath fenestration is an operation that involves the making of an incision in the connective tissue lining of the optic nerve in its portion behind the eye. It is not entirely clear how it protects the eye from the raised pressure, but it may be the result of either diversion of the CSF into the orbit or the creation of an area of scar tissue that lowers the pressure.[9] The effects on the intracranial pressure itself are more modest. Moreover, the procedure may lead to significant complications, including blindness in 1–2%.[5] The procedure is therefore recommended mainly in those who have limited headache symptoms but significant papilledema or threatened vision, or in those who have undergone unsuccessful treatment with a shunt or have a contraindication for shunt surgery.[9]

Shunt surgery, usually performed by neurosurgeons, involves the creation of a conduit by which CSF can be drained into another body cavity. The initial procedure is usually a lumboperitoneal (LP) shunt, which connects the subarachnoid space in the lumbar spine with the peritoneal cavity.[18] Generally, a pressure valve is included in the circuit to avoid excessive drainage when the person is erect. LP shunting provides long-term relief in about half the cases; others require revision of the shunt, often on more than one occasion—usually due to shunt obstruction. If the lumboperitoneal shunt needs repeated revisions, a ventriculoatrial or ventriculoperitoneal shunt may be considered. These shunts are inserted in one of the lateral ventricles of the brain, usually by stereotactic surgery, and then connected either to the right atrium of the heart or the peritoneal cavity, respectively.[5][9] Given the reduced need for revisions in ventricular shunts, it is possible that this procedure will become the first-line type of shunt treatment.[5]

It has been shown that in obese people, bariatric surgery (and especially gastric bypass surgery) can lead to resolution of the condition in over 95%.[5]

Prognosis

It is not known what percentage of people with IIH will remit spontaneously, and what percentage will develop chronic disease.[9]

IIH does not normally affect life expectancy. The major complications from IIH arise from untreated or treatment-resistant papilledema. In various case series, the long-term risk of ones vision being significantly affected by IIH is reported to lie anywhere between 10 and 25%.[5][9]

Epidemiology

On average, IIH occurs in about one per 100,000 people, and can occur in children and adults. The median age at diagnosis is 30. IIH occurs predominantly in women, especially in the ages 20 to 45, who are four to eight times more likely than men to be affected. Overweight and obesity strongly predispose a person to IIH: women who are more than ten percent over their ideal body weight are thirteen times more likely to develop IIH, and this figure goes up to nineteen times in women who are more than twenty percent over their ideal body weight. In men this relationship also exists, but the increase is only five-fold in those over 20 percent above their ideal body weight.[5]

Despite several reports of IIH in families, there is no known genetic cause for IIH. People from all ethnicities may develop IIH.[5] In children, there is no difference in rates between males and females.[7]

From national hospital admission databases it appears that the need for neurosurgical intervention for IIH has increased markedly over the period between 1988 and 2002. This has been attributed at least in part to the rising rates of obesity,[19] although some of this increase may be explained by the increased popularity of shunting over optic nerve sheath fenestration.[9]

History

The first report of IIH was by the German physician Heinrich Quincke, who described it in 1893 under the name serous meningitis[20] The term "pseudotumor cerebri" was introduced in 1904 by his compatriot Max Nonne.[21] Numerous other cases appeared in the literature subsequently; in many cases, the raised intracranial pressure may actually have resulted from underlying conditions.[22] For instance, the otitic hydrocephalus reported by London neurologist Sir Charles Symonds may have resulted from venous sinus thrombosis caused by middle ear infection.[22][23] Diagnostic criteria for IIH were developed in 1937 by the Baltimore neurosurgeon Walter Dandy; Dandy also introduced subtemporal decompressive surgery in the treatment of the condition.[14][22]

The terms "benign" and "pseudotumor" derive from the fact that increased intracranial pressure may be associated with brain tumors. Those people in whom no tumour was found were therefore diagnosed with "pseudotumor cerebri" (a disease mimicking a brain tumor). The disease was renamed benign intracranial hypertension in 1955 to distinguish it from intracranial hypertension due to life-threatening diseases (such as cancer);[24] however, this was also felt to be misleading because any disease that can blind someone should not be thought of as benign, and the name was therefore revised in 1989 to "idiopathic (of no identifiable cause) intracranial hypertension".[25][26]

Shunt surgery was introduced in 1949; initially, ventriculoperitoneal shunts were used. In 1971, good results were reported with lumboperitoneal shunting. Negative reports on shunting in the 1980s led to a brief period (1988–1993) during which optic nerve fenestration (which had initially been described in an unrelated condition in 1871) was more popular. Since then, shunting is recommended predominantly, with occasional exceptions.[5][9]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Wall, M (February 2017). "Update on Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension". Neurologic Clinics. 35 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2016.08.004. PMC 5125521. PMID 27886895.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 "Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension". National Eye Institute. April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ↑ "Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2015. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wakerley, BR; Tan, MH; Ting, EY (March 2015). "Idiopathic intracranial hypertension". Cephalalgia: An International Journal of Headache. 35 (3): 248–61. doi:10.1177/0333102414534329. PMID 24847166.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 5.18 5.19 5.20 5.21 5.22 5.23 5.24 Binder DK, Horton JC, Lawton MT, McDermott MW (March 2004). "Idiopathic intracranial hypertension". Neurosurgery. 54 (3): 538–51, discussion 551–2. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000109042.87246.3C. PMID 15028127.

- ↑ Sismanis A (July 1998). "Pulsatile tinnitus. A 15-year experience". American Journal of Otology. 19 (4): 472–7. PMID 9661757.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Soler D, Cox T, Bullock P, Calver DM, Robinson RO (January 1998). "Diagnosis and management of benign intracranial hypertension". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 78 (1): 89–94. doi:10.1136/adc.78.1.89. PMC 1717437. PMID 9534686. Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Friedman DI, Jacobson DM (2002). "Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension". Neurology. 59 (10): 1492–1495. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000029570.69134.1b. PMID 12455560.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 Acheson JF (2006). "Idiopathic intracranial hypertension and visual function". British Medical Bulletin. 79–80 (1): 233–44. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.131.9802. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldl019. PMID 17242038. Archived from the original on 2009-07-05. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Farb, RI; Vanek, I; Scott, JN; Mikulis, DJ; Willinsky, RA; Tomlinson, G; terBrugge, KG (May 13, 2003). "Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: the prevalence and morphology of sinovenous stenosis". Neurology. 60 (9): 1418–24. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000066683.34093.e2. PMID 12743224.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Ahmed, RM; Wilkinson, M; Parker, GD; Thurtell, MJ; Macdonald, J; McCluskey, PJ; Allan, R; Dunne, V; Hanlon, M; Owler, BK; Halmagyi, GM (Sep 2011). "Transverse sinus stenting for idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a review of 52 patients and of model predictions". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 32 (8): 1408–14. doi:10.3174/ajnr.a2575. PMID 21799038.

- ↑ "UOTW #5 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 17 June 2014. Archived from the original on 8 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ Peter P, Philip N, Singh Y (2012). "Reversal of MRI findings following CSF drainage in idiopathic intracranial hypertension". Neurol India. 60 (2): 267–8. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.96440. PMID 22626730.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Dandy WE (October 1937). "Intracranial pressure without brain tumor - diagnosis and treatment". Annals of Surgery. 106 (4): 492–513. doi:10.1097/00000658-193710000-00002. PMC 1390605. PMID 17857053.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Digre KB, Corbett JJ (2001). "Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): A reappraisal". Neurologist. 7: 2–67. doi:10.1097/00127893-200107010-00002.

- ↑ Smith JL (1985). "Whence pseudotumor cerebri?". Journal of Clinical Neuroophthalmology. 5 (1): 55–6. PMID 3156890.

- ↑ Teleb, MS; Cziep, ME; Lazzaro, MA; Gheith, A; Asif, K; Remler, B; Zaidat, OO (2013). "Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. A Systematic Analysis of Transverse Sinus Stenting". Interventional Neurology. 2 (3): 132–143. doi:10.1159/000357503. PMC 4080637. PMID 24999351.

- ↑ Yadav, YadR; Parihar, Vijay; Sinha, Mallika (1 January 2010). "Lumbar peritoneal shunt". Neurology India. 58 (2): 179–84. doi:10.4103/0028-3886.63778. PMID 20508332.

- ↑ Curry WT, Butler WE, Barker FG (2005). "Rapidly rising incidence of cerebrospinal fluid shunting procedures for idiopathic intracranial hypertension in the United States, 1988-2002". Neurosurgery. 57 (1): 97–108, discussion 97–108. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000163094.23923.E5. PMID 15987545.

- ↑ Quincke HI (1893). "Meningitis serosa". Sammlung Klinischer Vorträge. 67: 655.

- ↑ Nonne M (1904). "Ueber Falle vom Symptomkomplex "Tumor Cerebri" mit Ausgang in Heilung (Pseudotumor Cerebri)". Deutsche Zeitschrift für Nervenheilkunde (in German). 27 (3–4): 169–216. doi:10.1007/BF01667111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Johnston I (2001). "The historical development of the pseudotumor concept". Neurosurgical Focus. 11 (2): 1–9. doi:10.3171/foc.2001.11.2.3. PMID 16602675. Archived from the original on 2013-02-22. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ Symonds CP (1931). "Otitic hydrocephalus". Brain. 54: 55–71. doi:10.1093/brain/54.1.55. Archived from the original on 2009-02-11. Retrieved 2008-11-16. Also printed in Symonds CP (January 1932). "Otitic hydrocephalus". Br Med J. 1 (3705): 53–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3705.53. PMC 2519971. PMID 20776602.

- ↑ Foley J (1955). "Benign forms of intracranial hypertension; toxic and otitic hydrocephalus". Brain. 78 (1): 1–41. doi:10.1093/brain/78.1.1. PMID 14378448.

- ↑ Corbett JJ, Thompson HS (October 1989). "The rational management of idiopathic intracranial hypertension". Archives of Neurology. 46 (10): 1049–51. doi:10.1001/archneur.1989.00520460025008. PMID 2679506.

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay S (2001). "Pseudotumor cerebri". Archives of Neurology. 58 (10): 1699–701. doi:10.1001/archneur.58.10.1699. PMID 11594936.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |