Adenovirus infection

Adenovirus infection is a contagious viral infection caused by Adenoviruses, commonly resulting in a respiratory tract infection.[2] Typical symptoms range from those of a common cold, such as a stuffy nose, coryza and cough, to breathing problems as in pneumonia.[2][3] General symptoms include fever, tiredness, muscle aches, headache, tummy ache, sore throat and swollen neck glands.[3] Onset is usually 2-to-14 days after exposure to the virus.[8] However, some people have no symptoms.[5] A mild eye infection may either occur on its own, combined with a sore throat and fever, or as a more severe adenovirus eye disease with a painful red eye, intolerance to light and discharge.[6] Very young children may just have an earache.[3] It can also cause present as a gastroenteritis with vomiting, diarrhoea and tummy pain, with or without respiratory symptoms.[6]

In humans, the condition is generally caused by Adenoviruses types B, C, E and F.[13] Spread occurs mainly when an infected person is in close contact with another person.[9] This may occur by either fecal-oral route, airborne transmission or small droplets containing the virus.[9] Less commonly, the virus may spread via contaminated surfaces.[9] The illness is more likely to be severe in people with a weakened immune system.[11] Other respiratory complications include acute bronchitis, bronchiolitis and acute respiratory distress syndrome.[6][14] Other non-respiratory complications include meningitis, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, pericarditis, kidney problems and hepatitis.[6]

Diagnosis is by signs and symptoms, and a laboratory test is not usually required.[5] A PCR test on blood or respiratory secretions may detect adenovirus DNA.[5][11] Other conditions that appear similar include whooping cough and other flu-like illnesses.[3] Adenovirus gastroenteritis appears similar to diarrhoea diseases caused by other infections.[10]

Infection by adenovirus may be prevented by washing hands, avoiding touching own eyes, mouth and nose with unwashed hands, and avoiding being near sick people.[12] A live vaccine to protect against types 4 and 7 adenoviruses has been used in some military personnel.[12] Most adenovirus infections get better without any treatment.[12] Management is generally symptomatic and supportive.[12] Medicines to ease pain and reduce fever can be bought over the counter.[12] An affected person can remain contagious for weeks and months even after getting better.[2]

Adenovirus infections affect all ages.[4] Outbreaks typically occur in winter and spring, particularly in closed populations such as in hospitals, schools, and swimming pools.[8] Around 10% of respiratory infections in children,[8] and 75% of conjunctivitis cases are due to adenovirus infection.[8][15] By the the age of 10-years, most children have had at least one adenovirus infection.[6] In 2016, the Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that globally, around 75 million episodes of diarrhea among children under the age of five-years, were attributable to adenovirus infection.[10] The first adenoviral strains were isolated in 1953 by Rowe et al.[16]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms are variable, ranging from mild symptoms to severe illness.[6] They depend on the type of adenovirus, where it enters into the body, and on the age and well-being of the person.[3] Recognised patterns of clinical features include respiratory, eye, gastrointestinal, genitourinary and central nervous system.[3] There is also a widespread type that occurs in immunocompromised people.[3] Typical symptoms are of a mild cold or resembling the flu; fever, nasal congestion, coryza, cough, and pinky-red eyes.[7] Infants may also have symptoms of an ear infection.[3] Onset is usually two to fourteen days after exposure to the virus.[8] There may be tiredness, chills, muscle aches, or headache.[3] However, some people have no symptoms.[5] Generally, a day or two after developing a sore throat with large tonsils, glands can be felt in the neck.[17] Illness is more likely to be severe in people with weakened immune systems, particularly children who have had a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.[11] Sometimes there is a skin rash; this may be maculopapular, morbilliform, like rubella or less frequently petechial.[18]

Respiratory tract

Preschool children with adenovirus colds tend to present with a stuffy nose, runny nose and a tummy ache.[6] There may be a harsh barking cough.[6] It is frequently associated with a fever and a sore throat.[6] Up to one in five infants with bronchiolitis will have adenovirus infection, which can be severe.[6] Bronchiolitis obliterans is uncommon, but can occur if adenovirus causes pneumonia with prolonged fever, and can result in difficulty breathing.[6] It presents with a hyperinflated chest, expiratory wheeze and low oxygen.[6] Severe pneumonia is most common in very young children age 3-to-18 months and presents with sudden illness, ongoing cough, high fever, shortness of breath and a rapid breathing.[6] There are frequently wheezes and crackles on breathing in and out.[6]

Eyes

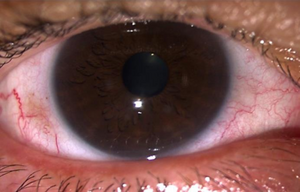

Adenovirus eye infection may present as a pinky-red eye.[6] 6 to 9-days following exposure to adenovirus, one or both eyes, typically in children, may be affected in association with fever, sore throat and lymphadenopathy (pharyngoconjunctival fever (PCF)).[3] The onset is usually sudden, and there is often nasal blockage.[6] Adenovirus infection can cause also cause a more severe eye disease.[6] Typically one eye is affected after an incubation period of up to a week.[6] The eye becomes scratchy, burning, watery and discharging, and gives the feeling something is in the eye.[6] It looks reddish and large bumps may be felt near the ear opening.[6] The symptoms may last around 10-days to 3-weeks.[6] It may be is associated with blurred vision, intolerance to light and swelling of the conjunctiva.[6][15] A sore throat and nasal congestion may or may not be present.[6] This tends to occur in epidemics, affecting predominantly adults.[6] In small children, it may be associated with high fever, sore throat, ear infection, diarrhea, and vomiting.[6]

-

Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis

-

Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis

-

Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis: periorbital swelling and ptosis, and severe chemosis

Gastrointestinal tract

Adenovirus infection can cause a tummy upset when it may present with diarrhoea, vomiting and tummy pain, with or without respiratory or general symptoms.[6] Children under the age of one-year appear particularly vulnerable.[10] However, it usually resolves within 3-days.[6] It appears similar to diarrhoea diseases caused by other infections.[10] There may be symptoms of intussusception, and appendicitis or mesenteric lymphadenitis.[6]

Other organs

Uncommonly the bladder may be affected, presenting with a sudden onset of burning and increased frequency of passing urine, followed by seeing blood in the urine a day or two later.[6] Nerve signs and symptoms may occur in adenovirus associated meningoencephalitis, which may occur in people with weakened immune systems such as with AIDS or lymphoma.[6] Adenovirus infection may result in symptoms of myocarditis, dilated cardiomyopathy, and pericarditis.[6] Other signs and symptoms depend on other complications such as dark urine, itching and yellow eyes in hepatitis, generally in people who have a weakened immune system.[6] Adenovirus is a rare cause of urethritis in men, when it may presents with burning on passing urine associated with red eyes and feeling unwell.[19]

Mechanism

Adenoviruses are everywhere and endemic.[21] More than 80 different adenovirus types infect humans through the respiratory, eye, or gastrointestinal tracts.[22] Adenovirus infection in humans are generally caused by adenoviruses types B, C, E and F.[13] The virus enters the body through the mouth, nose, or eyes, and then replicates, injuring the cells it invades, resulting in damage to the throat, nasal lining, eyes and respiratory tract and lungs.[3] Both innate and adaptive immunity are required to control adenovirus infection.[3] Although capable of infecting different organs, most infections go unnoticed.[21] The virus is frequently found in the throat and stool of healthy children, and most adults have antibodies to adenovirus, signalling previous infection.[21] It may re-activate at a later date.[4] It can also be transmitted by waterborne transmission, such as conjunctivitis from inadequately chlorinated swimming pools.[4] The virus can survive on objects for up to 30-days.[4]

Adenovirus types

Some types are capable of establishing persistent asymptomatic infections in tonsils, adenoids, and intestines of infected hosts, and shedding can occur for months or years.[23] Some adenoviruses (e.g., serotypes 1, 2, 5, and 6) have been shown to be endemic in parts of the world where they have been studied, and infection is usually acquired during childhood.[23] Other types cause sporadic infection and occasional outbreaks; for example, epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is associated with adenovirus serotypes 8, 19, and 37.[23] Epidemics of febrile disease with conjunctivitis are associated with waterborne transmission of some adenovirus types, often centering on inadequately chlorinated swimming pools and small lakes.[23] ARD is most often associated with adenovirus types 4 and 7 in the United States.[23] Enteric adenoviruses 40 and 41 (species F) can cause severe diarrhoea in young children.[10] For some adenovirus serotypes, the clinical spectrum of disease associated with infection varies depending on the site of infection; for example, infection with adenovirus 7 acquired by inhalation is associated with severe lower respiratory tract disease, whereas oral transmission of the virus typically causes no or mild disease.[23] Outbreaks of adenovirus-associated respiratory disease have been more common in the late winter, spring, and early summer; however, adenovirus infections can occur throughout the year.[23]

The association of Ad36 and obesity is established. [24]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is by signs and symptoms, and a laboratory test is not usually required.[5] In some circumstances such as severe disease, when a diagnosis needs to be confirmed, a PCR test on blood or respiratory secretions may detect adenovirus DNA.[5][11] Adenovirus can be isolated by growing in cell cultures in a laboratory.[4] Other conditions that appear similar include whooping cough, influenza, parainfluenza, and respiratory syncytial virus.[3] Since adenovirus can be excreted for prolonged periods, the presence of virus does not necessarily mean it is associated with disease.[25]

Other conditions that appear similar include whooping cough, influenza, parainfluenza, and respiratory syncytial virus.[3]

-

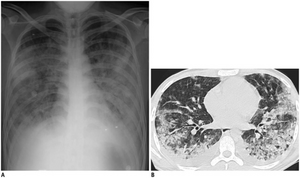

Adenovirus pneumonia chest X-ray and CT-scan

Prevention

Infection by adenovirus may be prevented by washing hands, avoiding touching own eyes, mouth and nose before washing hands and avoiding being near sick people.[12] Strict attention to good infection-control practices is effective for stopping transmission in hospitals of adenovirus-associated disease, such as epidemic keratoconjunctivitis.[23] Maintaining adequate levels of chlorination is necessary for preventing swimming pool-associated outbreaks of adenovirus conjunctivitis.[12] A live adenovirus vaccine to protect against types 4 and 7 adenoviruses has been used in some military personnel.[12] Rates of adenovirus disease fell among military recruits following the introduction a live oral vaccine against types 4 and 7.[3] Stocks of the vaccine ran out in 1999 and rates of disease increased until 2011 when the vaccine was re-introduced.[3]

Treatment

Treatment is generally symptomatic and supportive.[12] Medicines to ease pain and reduce fever can be bought over the counter.[12] For adenoviral conjunctivitis, a cold compress and lubricants may provide some relief of discomfort.[26] Steroid eye drops may be required if the cornea is involved.[26] Most adenovirus infections get better without any treatment.[12]

Outcome

After recovery from adenovirus infection, the virus can be carried for weeks or months.[8]

Adenovirus can cause severe necrotizing pneumonia in which all or part of a lung has increased translucency radiographically, which is called Swyer-James Syndrome.[27] Severe adenovirus pneumonia also may result in bronchiolitis obliterans, a subacute inflammatory process in which the small airways are replaced by scar tissue, resulting in a reduction in lung volume and lung compliance.[27]

Epidemiology

Most occur in children under 5-years.[3] By the age of 10-years, most children have had at least one adenovirus infection.[6] Adenovirus infections occur sporadically throughout the year, and outbreaks can occur particularly in winter and spring.[8] Epidemics may spread more quickly in closed populations such as in hospitals, nurseries, long-term care facilities, boarding schools, orphanages and nurseries.[8] Where there is a common source of infection such as a contaminated swimming pool, the pharyngoconjunctival fever is common.[28] Severe disease is rare in people who are usually healthy.[8] Around 10% of respiratory infections in children are caused by adenoviruses.[8]

Adenoviruses are the most common viruses causing an inflamed throat.[17] 75% of conjunctivitis cases are due to adenovirus infection.[15] Under 2-year olds are particularly susceptible to adenovirus gastroenteritis by types 40 and 41, with type 41 being more common than type 40.[10] Some large studies have revealed type 40/41 adenovirus as one of the second most common causes of diarrhoea in children in low and middle income countries; the most common being rotavirus.[10] In 2016, the Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that globally, around 75 million episodes of diarrhea among children under the age of five-years, were attributable to adenovirus infection, with a mortality of near 12%.[10]

History

The first adenoviral strains were isolated from adenoids in 1953 by Rowe et al.[16] Later, during studies on rotavirus diarrhea, the wider use of electron microscopy resulted in detecting previously unrecognized adenoviruses types 40 and 41, subsequently found to be important in causing tummy upsets in children.[6]

The illness made headlines in Texas in September 2007, when a so-called "boot camp flu" sickened hundreds at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio.[29] In 2018, outbreaks occurred in an adult nursing home in New Jersey, and a college campus in Maryland.[4] In 2020, as a result of infection control measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of adenovirus diarrhoea declined significantly in China.[30]

Social and cultural

Research in adenovirus infection has generally been limited relative to other respiratory disease viruses.[10] The impact of type-40/41 adenovirus diarrhoea is possibly underestimated.[10]

Other animals

Dogs can be affected by adenovirus infection.[31] Severe liver damage is a classical infectious disease seen in unvaccinated dogs.[32]

References

- ↑ "Adenovirus Infections, Human (Concept Id: C0001487) - MedGen - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2021-10-20. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Adenovirus Clinical Overview for Healthcare Professionals | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 29 November 2021. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 Ison, Michael G. (2020). "341. Adenovirus diseases". In Goldman, Lee; Schafer, Andrew I. (eds.). Goldman-Cecil Medicine. Vol. 2 (26th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 2162-2164. ISBN 978-0-323-55087-1. Archived from the original on 2023-03-20. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 "Adenovirus Infection and Outbreaks: What You Need to Know" (PDF). Am J Respir Crit Care Med. American Thoracic Society. 199: 13–14. 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-03-03. Retrieved 2022-05-03.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Tesini, Brenda L. (April 2022). "Adenovirus Infections - Infectious Diseases". MSD Manual Professional Edition. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 6.28 6.29 6.30 6.31 6.32 6.33 6.34 6.35 6.36 6.37 6.38 6.39 6.40 6.41 Shieh, Wun-Ju (10 September 2021). "Human adenovirus infections in pediatric population - An update on clinico-pathologic correlation". Biomedical Journal: S2319–4170(21)00109–8. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2021.08.009. ISSN 2320-2890. PMID 34506970. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Adenovirus: symptoms". www.cdc.gov. 16 March 2021. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 Lynch, Joseph P.; Kajon, Adriana E. (August 2016). "Adenovirus: Epidemiology, Global Spread of Novel Serotypes, and Advances in Treatment and Prevention". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 37 (4): 586–602. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1584923. ISSN 1069-3424. PMID 27486739. Archived from the original on 2022-04-08. Retrieved 2022-04-27.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "Adenovirus: transmission". www.cdc.gov. 29 November 2021. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 Lee, B; Damon, CF; Platts-Mills, JA (October 2020). "Pediatric acute gastroenteritis associated with adenovirus 40/41 in low-income and middle-income countries". Current opinion in infectious diseases. 33 (5): 398–403. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000663. PMID 32773498. Archived from the original on 2022-04-18. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Arnold, Amber; MacMahon, Eithne (1 December 2021). "Adenovirus infections". Medicine. 49 (12): 790–793. doi:10.1016/j.mpmed.2021.09.013. ISSN 1357-3039. Archived from the original on 24 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 "Adenovirus: preventing and treating Adenovirus". www.cdc.gov. 29 November 2021. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Flint, S. Jane; Nemerow, Glen R. (2017). "8. Pathogenesis". Human Adenoviruses: From Villains To Vectors. Singapore: World Scientific. p. 153-183. ISBN 978-981-310-979-7. Archived from the original on 2023-03-20. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ↑ Radke, Jay R.; Cook, James L. (June 2018). "Human adenovirus infections: update and consideration of mechanisms of viral persistence". Current opinion in infectious diseases. 31 (3): 251–256. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000451. ISSN 0951-7375. PMID 29601326. Archived from the original on 2022-04-21. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Labib, Bisant A; Minhas, Bhawanjot K; Chigbu, DeGaulle I (17 March 2020). "Management of Adenoviral Keratoconjunctivitis: Challenges and Solutions". Clinical Ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 14: 837–852. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S207976. ISSN 1177-5467. PMID 32256043.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Haveman, Lianne M.; Bierings, Marc; Wolf, Tom F.W. (2004). "12. Adenovirus". In Kimpen, Jan L. L.; Ramilo, Octavio (eds.). The Microbe-Host Interface in Respiratory Tract Infections. Norfolk: CRC Press. p. 271. ISBN 0-8493-3646-5. Archived from the original on 2023-03-20. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 White, Veronica; Ruperelia, Prina (2020). "28.Respiratory disease". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 947. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2023-01-11. Retrieved 2022-04-26.

- ↑ Michaels, Marian `G.; Williams, John V. (2023). "13. Infectious diseases". In Zitelli, Basil J.; McIntire, Sara C.; Nowalk, Andrew J.; Garrison, Jessica (eds.). Zitelli and Davis' Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-323-77788-9. Archived from the original on 2023-03-20. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ↑ Young, Ashley; Toncar, Alicia; Wray, Anton A. (2022). "Urethritis". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- ↑ Waye, Mary Miu Yee; Sing, Chor Wing (25 October 2010). "Anti-Viral Drugs for Human Adenoviruses". Pharmaceuticals. 3 (10): 3343–3354. doi:10.3390/ph3103343. ISSN 1424-8247.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Gompf, Sandra G. (15 April 2021). "Adenovirus: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". www.emedicine.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ↑ Greber, Urs F.; Flatt, Justin W. (29 September 2019). "Adenovirus Entry: From Infection to Immunity". Annual Review of Virology. 6 (1): 177–197. doi:10.1146/annurev-virology-092818-015550. ISSN 2327-056X. PMID 31283442. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 25 April 2022.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/revb/respiratory/eadfeat.htm "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: https://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/revb/respiratory/eadfeat.htm "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-03.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Cancelier, Ana Carolina Lobor; Schuelter-Trevisol, Fabiana; Trevisol, Daisson José; Atkinson, Richard L. (4 March 2022). "Adenovirus 36 infection and obesity risk: current understanding and future therapeutic strategies". Expert Review of Endocrinology & Metabolism. 17 (2): 143–152. doi:10.1080/17446651.2022.2044303. ISSN 1744-6651. PMID 35255768. Archived from the original on 8 May 2022. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ↑ "Clinical Diagnosis of Adenovirus". www.cdc.gov. 29 November 2021. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Vaz, Francis; Mehta, Nischcay; Hamilton, Robin D. (2020). "27. Ear, nose and throat and eye disease". In Feather, Adam; Randall, David; Waterhouse, Mona (eds.). Kumar and Clark's Clinical Medicine (10th ed.). Elsevier. p. 917. ISBN 978-0-7020-7870-5. Archived from the original on 2022-04-25. Retrieved 2022-04-24.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Kliegman, Robert; Richard M Kliegman (2006). Nelson essentials of pediatrics. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-0-8089-2325-1.

- ↑ Bower, John R. (2022). "33. Pharyngitis". In Jong, Elaine C.; Stevens, Dennis L. (eds.). Netter's Infectious Diseases (2nd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 168–173. ISBN 978-0-323-71159-3. Archived from the original on 2022-05-12. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ↑ New York Times Archived 2015-06-11 at the Wayback Machine article New Form of Virus Has Caused 10 Deaths in 18 Months published November 16, 2007

- ↑ Zhang, Junfeng; Cao, JiaJia; Ye, Qing (26 April 2022). "Nonpharmaceutical interventions against the COVID-19 pandemic significantly decreased the spread of enterovirus in children". Journal of Medical Virology. doi:10.1002/jmv.27806. ISSN 1096-9071. Archived from the original on 5 May 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ↑ Gonzales, Anthony L.; King, Lesley G. (2019). "37. Bronchopneumonia". In Drobatz, Kenneth J.; Hopper, Kate; Rozanski, Elizabeth A.; Silverstein, Deborah C. (eds.). Textbook of Small Animal Emergency Medicine. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-119-02893-2. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

- ↑ De Jonge, Bert; Van Brantegem, Leen; Chiers, Koen (2020). "Infectious canine hepatitis, not only in the textbooks : a brief review and three case reports". Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift. 89 (5): 284–291. ISSN 0303-9021. Archived from the original on 2022-05-05. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

External links

| Classification |

|---|