User:QuackGuru/Sand 25

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31252671/ E-Cigarettes are More Addictive than Traditional Cigarettes-A Study in Highly Educated Young People

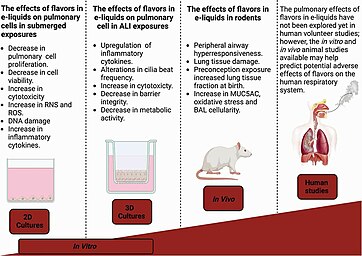

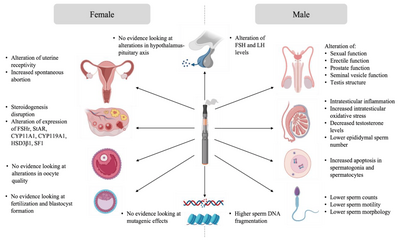

Fig. 4

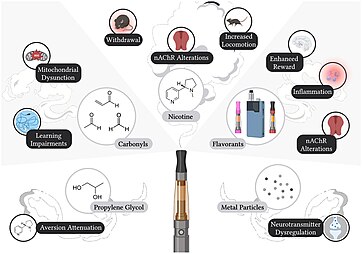

Health hazards of e-cigarette use

Developmental nicotine exposure engenders intergenerational downregulation and aberrant posttranslational modification of cardinal epigenetic factors in the frontal cortices, striata, and hippocampi of adolescent mice

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?linkname=pubmed_pubmed_citedin&from_uid=32138755

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37286509/ [3] (PMCID: available on 2024-06-07)

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36804178/ [4]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36777290/ [5]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36728241/ [6] (PMCID: available on 2024-04-01)

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36900893/ [7]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37185310/ [8]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36736923/ [9]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36370069/ [10]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37314028/ [11]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34615737/ [12]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37320902/ [13]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36915837/ [14]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36806607/ [15]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36773789/ [16]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37183777/ [17]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36399154/ [18]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36882378/ [19] (PMCID: available on 2024-07-01)

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37202029/ [20]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36804352/ [21]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36120959/ [22]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36735735/ [23]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36833024/ [24]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36427562/ [25]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35998874/ [26]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36641959/ [27]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37295941/ [28]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36736944/ [29]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37290827/ [30]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37159065/ [31]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36767274/ [32]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36808672/ [33]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36208090/ [34]

Unable to open[35]

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35787100/ (available on 2024-02-01)

The benefits and the health effects of electronic cigarettes are uncertain.[42] There is considerable variation among e-cigarettes and in their liquid ingredients and as a consequence there are differences in the aerosol delivered to the user.[43] Regulated US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) products such as nicotine inhalers may be safer than e-cigarettes,[44] but e-cigarettes are generally seen as safer than combusted tobacco products[note 1][50] such as cigarettes and cigars.[51] Since vapor does not contain tobacco and does not involve combustion, users may avoid several harmful constituents usually found in tobacco smoke,[52] such as ash, tar, and carbon monoxide.[53] However, vaping is more dangerous in the short-term than smoking.[48][54] Because of the risk of nicotine exposure to the fetus and adolescent causing long-term effects to the growing brain, the World Health Organization does not recommend it for children, adolescents, pregnant women, and women of childbearing age.[55] Vaping itself has no proven benefits[48] and with or without nicotine it cannot be considered harmless.[56] Their indiscriminate use is a threat to public health.[57]

The long-term effects of e-cigarette use are unknown[58][59][60] and unclear.[61] Short-term use may lead to death.[48] Less serious adverse effects include abdominal pain, headache, blurry vision,[62] throat and mouth irritation, vomiting, nausea, and coughing.[43] They may produce similar adverse effects compared to tobacco use.[63] E-cigarettes reduce lung function, reduce cardiac muscle function, and increase inflammation.[64] In 2019 and 2020, there was an outbreak of severe lung illness linked to vaping in the US[65] and Canada,[66] with 68 confirmed deaths in the US,[note 2][65] and one confirmed death in Europe.[71] There are also risks from misuse or accidents[52] such as nicotine poisoning (especially among small children[72]),[73] contact with liquid containing nicotine,[74] fires caused by vaporizer malfunction,[43] and explosions resulting from extended charging, unsuitable chargers, design flaws,[52] or user modifications.[75] Battery explosions are caused by an increase in internal battery temperature and some have resulted in severe skin burns.[76] There is a small risk of a battery explosion in devices modified to increase battery power.[77]

The cytotoxicity of e-liquids varies,[78] and contamination with various chemicals have been detected in the liquid.[79] Metal parts of e-cigarettes in contact with the e-liquid can contaminate it with metal particles.[52] Many chemicals including carbonyl compounds such as formaldehyde can inadvertently be produced when the nichrome wire (heating element) that touches the e-liquid is heated and chemically reacted with the liquid.[80] The later-generation and "tank-style" e-cigarettes with a higher voltage (5.0 V[78]) may generate equal or higher levels of formaldehyde compared to smoking.[81] Nicotine is associated with cardiovascular disease, increased serum cholesterol levels, and possible birth defects.[82] Children, youth,[47] and young adults are especially sensitive to the effects of nicotine.[83] Several studies demonstrate nicotine is carcinogenic.[84] Public health authorities do not recommend nicotine use for non-smokers.[85] Propylene glycol, glycerin, volatile organic compounds, and free radicals can impair lung health.[86] Many flavors are irritants[87] and certain flavoring agents can induce respiratory toxicity.[88]

E-cigarettes create vapor that consists of fine and ultrafine particles of particulate matter, with the majority of particles in the ultrafine range.[43] The vapor contains propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, flavors, small amounts of toxicants,[43] carcinogens,[note 3][89] and heavy metals, as well as metal nanoparticles, and other substances.[43] Exactly what the vapor consists of varies significantly in composition and concentration across and within brands, and depends on the e-liquid contents, the device design, and user behavior, among other factors.[note 4][90] E-cigarette vapor potentially contains harmful chemicals not found in tobacco smoke[91] such as propylene glycol.[92] E-cigarette vapor contains fewer toxic chemicals,[43] and lower concentrations of potentially toxic chemicals than in cigarette smoke.[93] Concern exists that the exhaled e-cigarette vapor may be inhaled by bystanders, particularly indoors.[94] There is limited information available on the environmental issues around production, use, and disposal of e-cigarettes that use cartridges.[95] E-cigarettes that are not reusable may contribute to the problem of electronic waste.[96]

Health effects

Overview of benefits and effects

Reviews on the safety of electronic cigarettes, evaluating roughly the same studies, have reached significantly different conclusions.[99] Broad-ranging statements regarding their safety cannot be reached because of the vast differences of devices and e-liquids available.[100] A consensus has not been established for the benefits as well as the effects related to their use.[88] A substantial amount of research has been conducted in the past decade prior to 2020 to examine the health effects of e-cigarette use, often providing conflicting evidence and claims.[42] What will cause the most or least undesirable effects of various blends of solvents, flavoring, and nicotine in e-liquids is unknown.[83]

There is considerable variation in e-cigarette product technologies as well as differing amounts of chemicals in their liquid solution, including an assortment of nicotine strengths and a vast array of additives and flavors, and as a consequence there are differences in the contents of the aerosol inhaled as well as exhaled by the user.[43] Due to the large variation in the quantities of each constituent across products and an ever-evolving product marketplace, it is challenging to fully understand the clinical relevance of e-cigarette use on the individual's health.[40] Although there is inconsistencies among the methodologies used (detection method, liquid or aerosol, animal models, conditions), the data generated by these investigations remains informative.[101] Moreover, due to various methodological issues, severe conflicts of interest, and inconsistent research, no firm views can be made regarding their effects.[102] However, e-cigarette use with or without nicotine cannot be considered harmless.[56] Nicotine-free e-cigarette aerosol contains chemicals that cause cancer as well as chemicals associated with severe lung damage.[61]

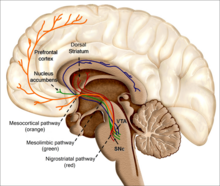

E-cigarettes cannot be considered absolutely safe because there is no safe level for carcinogens.[103] An uncountable amount of studies aimed at evaluating e-cigarette potential consequences on human health and the most updated panorama of scientific literature provides increasing evidence of vaping harmfulness.[104] Among e-cigarettes adverse health effects, respiratory impact is by far the most extensively studied.[104] Nicotine is the most studied biologically active chemical present in e-cigarettes, and several of the cardiovascular effects of e-cigarettes have been attributed to this alkaloid from the tobacco plant.[105] Nicotine has well-established effects on the metabolism and cardiovascular system.[105] In the same way as conventional cigarettes smokers, vapers' pulmonary epithelium is typically damaged and bronchial mucosa chronically inflamed.[104] Vaping has been promoted as being safer than cigarette smoking, though users can be inhaling toxicants such as diacetyl and carcinogens such as formaldehyde[106] and users can be inhaling contaminants such as traces of arsenic and other heavy metals.[63] Because of the belief that vaping is less dangerous than traditional cigarettes, vapers may vape products at a more frequent pace than traditional cigarettes and, as a consequence, produce higher levels of second-hand contaminants.[107] Vaping itself has no proven benefits,[48] and it is a deliberate exposure in contrast to numerous other toxicological exposures.[108] The potential benefits of nicotine vaping are significantly outweighed by its unwanted effects, such as threat of addiction, cancer, heart disease, hypertension, respiratory infections, and gastrointestinal discomfort.[109]

E-cigarettes were initially positioned as a "healthy alternative", though they may produce similar adverse effects compared to tobacco use.[63] There is emerging evidence demonstrating adverse effects attributable to e-cigarette use on every single human organ system.[111] Whether e-cigarettes are helping smokers or creating a new source of addiction is extensively being debated.[112] The overall public health effect related to their use is actively debated.[113] Available evidence on the benefits and risks of e-cigarette use are mixed and interpreted differently.[114] Some believe that e-cigarettes have the potential to reduce the burden of disease in smokers while others worry about the impact on public health and do not recommend, and even ban, their use.[114] Debates about the population health impact of alternative nicotine delivery products (i.e., e-cigarettes) are ongoing.[114]

Limited research

The long-term consequences from e-cigarette use on death and disease are unclear.[115] The risks from long-term use of nicotine as well as other toxicants that are unique to e-cigarettes are uncertain.[116] The potential long-term effects of e-cigarette consumption have been scarcely investigated.[117] Disease caused by tobacco has a latency period of no less than 25 years.[118] Therefore, as of 2019, it will conservatively take two decades until firm conclusions from long-term studies on using e-cigarettes are published.[118] Epidemiological data on cancer findings takes at least 20 to 40 years to become available.[119] As of 2023, evidence of the harms of e-cigarettes has been unfolding slowly and has been documented in many reviews and reports worldwide.[120]

The health effects related to e-cigarette use is mostly unknown.[121] Most of the available articles reported are limited in their design, methodology, and the used exposure time and had a lack of long-term follow-up.[122] There is insufficient data regarding the health benefits of vaping.[123] E-cigarettes have the potential for benefit and harm, the nature and scale of each being uncertain in the absence of ample evidence.[124] There is limited available research regarding their effects on vulnerable groups such as minors.[125] The effect on population health from e-cigarettes is unknown.[44] The chemical characteristics of the short-lived free radicals and long-lived free radicals produced from e-cigarettes is unclear.[126] The knowledge of possible acute and long-term health effects of aerosols inhaled from e-cigarettes is limited partially due to incomplete awareness of physical phenomena related to e-cigarette aerosol dynamics.[127]

In August 2014, the Forum of International Respiratory Societies stated that e-cigarettes have not been demonstrated to be safe.[128] Health Canada has stated that, "their safety, quality, and efficacy remain unknown."[129] The National Institute on Drug Abuse stated that "There are currently no accepted measures to confirm their purity or safety, and the long-term health consequence of e-cigarette use remain unknown."[130] A 2017 review found "There is a justifiable concern that any broad statement promoting e-cig safety may be unfounded considering the lack of inhalational toxicity data on the vast majority of the constituents in e-cigs. This is particularly true for individuals with existing lung disease such as asthma."[131]

Alternative to smoking

Tobacco companies have deliberately promoted the use of alternatives to traditional cigarettes with supposedly safer tobacco products, such as e-cigarettes, in an effort to reduce the harm caused by tobacco consumption.[note 5][135] There is a lack of evidence in favor of using e-cigarettes as a safe option to classical cigarettes and as a substitute to public health approaches that aim at curtailing tobacco use.[136]

A 2019 editorial in The Lancet stated that there is no solid proof showing that vaping is safer than cigarettes, but this conclusion was "criticized by Professor JN Newton, Director of Health Improvement at Public Health England, who stated that there is an international consensus that the use of e-cigarettes is likely to be much less harmful than smoking."[137] Clinical trials and other studies have demonstrated that e-cigarettes are not a safer option.[138] According to a 2020 review, e-cigarettes are repeatedly popularized and regarded as a safer option to classical cigarettes, but they are unsafe to use and therefore can hardly be construed as being less hazardous as proclaimed by the companies who are selling such devices.[139] Since e-liquids and vaping aerosols contain nicotine and many of the same toxic chemicals and carcinogens as classical cigarettes do, it may be assumed, especially when taking into account the growing evidence of toxic tobacco inhalation that has been observed in the users of these devices, that there is the possibility that vaping may result in similar unwanted effects..[140]

Vaping long-term is anticipated to raise the risk of developing some of the diseases linked to smoking.[87] Since vapor does not contain tobacco and does not involve combustion, users may avoid several harmful constituents usually found in tobacco smoke,[52] such as ash, tar, and carbon monoxide.[note 6][53] A 2014 review found that e-cigarette aerosol contains far fewer carcinogens than tobacco smoke, and concluded that e-cigarettes "impart a lower potential disease burden" than traditional cigarettes.[142] The public health community is divided, even polarized, over how the use of these devices will impact the tobacco epidemic.[143] Some tobacco control advocates predict that e-cigarettes will increase rates of cigarette uptake, especially among youth.[143] Others envision that these devices have potential for aiding cessation efforts, or reducing harm among people who continue to smoke.[143] Scientific studies advocate caution before designating e-cigarettes as beneficial but vapers continue to believe they are beneficial.[144]

E-cigarette vapor contains higher levels of carcinogens and toxicants than in an US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulated nicotine inhaler, which suggests that regulated US FDA devices may deliver nicotine more safely.[44] E-cigarettes are generally seen as safer than combusted tobacco products[51][145][50] such as cigarettes and cigars.[51] A 2019 review concluded: "no long term vaping toxicological/safety studies have been done in humans; without these data, saying with certainty that e-cigarettes are safer than combustible cigarettes is impossible."[37] Early research seemed to indicate that vaping might be safer than traditional cigarettes and provide a different method to give up smoking, though mounting evidence does not substantiate this.[45] Evidence has not been presented to demonstrate that e-cigarettes are less dangerous than tobacco.[46] The short-term health effects of e-cigarettes can be severe[47] and the short-term harms of e-cigarettes is greater than tobacco products.[48] E-cigarettes are frequently viewed as a safer alternative to conventional cigarettes; however, evidence to support this perspective has not materialized.[49] This appears to be due to the presence of toxicants in e-liquid composition, their adverse effects in animal models, association with acute lung injury and cardiovascular disease, and ability to modulate different cell populations in the lung and blood towards pro-inflammatory phenotypes.[49] Short-term e-cigarette use may lead to death.[48]

The surge in vaping among youth and the vaping-induced lung illness epidemic has increased the controversy surrounding vaping and casts doubt about their feasibility for public health gains as an alternative to traditional cigarettes.[137] The US National Association of County and City Health Officials has stated, "Public health experts have expressed concern that e-cigarettes may increase nicotine addiction and tobacco use in young people."[146] No long-term studies have evaluated future tobacco use as a result of e-cigarette use.[147] E-cigarette vapor potentially contains harmful substances not found in tobacco smoke[91] such as propylene glycol and/or glycerin and various flavoring agents along with other unknown chemicals.[92]

Opinions that e-cigarettes are a safe substitute to traditional cigarettes may compromise tobacco control efforts.[148] The American Cancer Society has stated, "E-cigarettes pose a threat to the health of users and the harms are becoming increasingly apparent. In the past few years, the use of these products has increased at an alarming rate among young people in significant part because the newest, re-engineered generation of e-cigarettes more effectively delivers large amounts of nicotine to the brain."[149] The Canadian Cancer Society has stated that, "A few studies have shown that there may be low levels of harmful substances in some e-cigarettes, even if they don't have nicotine."[150] In the UK a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline did not recommend e-cigarettes as there are questions regarding the safety, efficacy, and quality of these products.[151] While quitting smoking may be firmly recommended for smokers who have asthma, it is not clear whether replacing e-cigarettes for cigarettes is a universally safer alternative.[131] The American Diabetes Association states "There is no evidence that e-cigarettes are a healthier alternative to smoking."[152]

Studies evaluating whether e-cigarettes are less harmful than cigarettes are inconclusive.[122] As of 2020, there is still a lack of evidence that they are safe during repeated inhalation in long-term use.[122] Long-term data showing that vaping is a "healthier alternative" than cigarette smoking does not exist.[44]

Effects on increased availability of vaping products

A serious concern regarding e-cigarettes is that they could entice children to initiate smoking, either by subjecting them to nicotine that leads to smoking or by making smoking appear more acceptable again.[153] Concerns exist in respect to adolescence vaping due to studies indicating that nicotine use could induce potentially harmful effects on the growing brain.[154]

The medical community is concerned that increased availability of e-cigarettes could increase worldwide nicotine dependence, especially among the young as they are enticed by the various flavor options e-cigarettes have to offer.[155] Since vaping does not produce smoke from burning tobacco, the opponents of e-cigarettes fear that traditional smokers will substitute vaping for smoking in settings where smoking is not permitted without any real intention of quitting traditional cigarettes.[155] Furthermore, vaping in public places, coupled with recent e-cigarette commercials on national television, could possibly undermine or weaken current antismoking regulations.[155] Fear exists that wide-scale promotion and use of e-cigarettes, fueled by an increase in advertising of these products, may carry substantial public health risks.[156] Public health professionals have voiced concerns regarding vaping while using other tobacco products - particularly combustible products.[157]

A 2017 review states that the "Increased concentration of the ENDS market in the hands of the transnational tobacco companies is concerning to the public health community, given the industry's legacy of obfuscating many fundamental truths about their products and misleading the public with false claims, including that low-tar and so-called "light" cigarettes would reduce the harms associated with smoking. Although industry representatives are claiming interest in ENDS because of their harm-reduction potential, many observers believe that profit remains the dominant motivation."[157] E-cigarettes are expanding the tobacco epidemic by bringing lower-risk youth into the market, many of whom then transition to smoking cigarettes.[158] A 2016 review recommended the precautionary principle to be used for e-cigarettes because of the long history of the tobacco crisis, in order to assess their benefits and long-term effects and to avoid another nicotine crisis.[159]

Effects on dual vaping and smoking use

![The figure shows the known and unknown health effects of vaping in comparison to cigarette smoke. The major toxic effects of compounds found in cigarette smoke (right lung) and in vaping aerosols (left lung) are lung inflammation, oxidative stress, cell death, impaired immune response, DNA damage, and epigenetic modifications. The respiratory diseases caused by cigarette smoke (lung cancer, COPD [emphysema and/orobstruction of airways]) are not yet established to be caused by vaping (represented by question marks in the left lung). There is an association with the presence of lipid-laden macrophages and the use of vaping products. E-cigarettes containing THC and vitamin E acetate or nicotine can cause a vaping-induced lung injury disease.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6f/Health_effects_of_vaping_in_comparison_to_cigarette_smoke.png/362px-Health_effects_of_vaping_in_comparison_to_cigarette_smoke.png)

The entrance of large US tobacco manufacturers, such as Altria Group, Reynolds American, and Lorillard, into the e-cigarette sector raises many potential public health issues.[162] Instead of pushing for quitting smoking, the tobacco industry may promote e-cigarettes as a way to get around clean indoor air laws, which promotes dual use and the increased sale of traditional cigarettes.[162] A 2015 review recommended the precautionary principle to be used because dual use could end up being an additional risk.[99] The industry could also lead vapers to tobacco products, which would increase instead of decrease overall addiction.[162] Concerns exist that the emergence of e-cigarettes may benefit Big Tobacco to sustain an industry for tobacco.[163]

Many continue to use both, exposing themselves to the harms of tobacco smoking and e-cigarette use.[164] The long-term research on the effects of dual use of tobacco smoking and vaping are not available.[165] A 2018 study found that both e-cigarette and cigarette users had similar levels of metals toluene, benzene, and carbon disulfide, while dual users had the greatest amount of exposure to nicotine, tobacco biomarkers, metals toluene, benzene, and carbon disulfide.[140] Vaping can hinder smokers from trying to quit, resulting in increased tobacco use and associated health problems.[166] Compared to just smoking, dual use of smoking and vaping may increase the chance of developing heart disease, lung disease, and cancer.[167] There is a greater risk for a heart attack with the use of both e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes.[168] Quitting smoking entirely would probably have much greater beneficial effects to overall health than vaping to decrease the number of cigarettes smoked.[43]

Ten large, good-quality surveys, including between 3,400 and almost 450,00 persons from the general population, investigated the cardiovascular and metabolic health effects of dual use.[114] The best available of these studies had adjusted for tobacco consumption and found higher HbA1c levels in dual users than in exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes, but significance levels were not tested.[114] Four of the good-quality surveys investigated cardiovascular risk factors and found that dual users had a significantly higher unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios of cardiovascular disease, significantly higher prevalence unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios of cardiovascular risk factors and diagnosis of metabolic syndrome, significantly higher unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios of elevated human c-reactive protein, significantly higher risk of stroke, significantly higher prevalence of arrythmia, significantly higher unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios of elevated c-reactive protein, and significantly higher unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios of abdominal obesity than exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes.[114] The two remaining surveys found higher unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios of myocardial infarction and stroke, but significance level was not tested, and higher but not significant unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios of hypertension in dual users than in exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes.[114] Furthermore, one survey found that dual users had similar fasting glucose as exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes, and another study found the same levels of insulin resistance.[114]

A 2020 clinical study performed vascular function testing in almost 500 young persons and reported that dual users had similar arterial stiffness as exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes.[114] Large good-quality surveys (only one did not weight data) including adults found that dual users had significantly worse fitness and significantly higher levels of uric acid and prevalence of hyperuricemia compared with exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes.[114] Large surveys including adolescent dual users reported insufficient sleep significantly more often than exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes, and higher odds of dental problems.[114] In a large survey, homeless persons with dual use reported significantly higher rates of asthma and cancer compared to exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes.[114] Finally, in a small human clinical study in 2020, dual users had higher levels of most biomarkers of systemic inflammation than exclusive smoking of conventional cigarettes, but the difference was not significant.[114]

Evidence on the effects of dual e-cigarette and traditional cigarette use compared to using one product alone is limited.[42] Dual users reported a lower general health score, and more difficulty in breathing in the past month, compared to cigarette-only users.[169] Additionally, a significant difference was observed in the history of arrhythmia between cigarette-only users (14.2%) and dual users (17.8%).[169] More respiratory symptoms were found in dual smokers than in smokers who did not use e-cigarettes, and the possibility of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome was more likely to be observed in dual users.[169] A positive association between dual use and the prevalence of asthma was reported in one systematic review in 2021, while a 2021 meta-analysis found that the association with asthma prevalence was even stronger for dual use than for traditional cigarette use alone.[42] Temporality and a dose–response relationship were not determined due to the cross-sectional nature of the associations and lack of information on the intensity and duration of use.[42] A 2020 systematic review concluded that e-cigarette use, as compared to traditional cigarette use, contributes independently to respiratory risk.[42]

Effects on smoking cessation

The safety of e-cigarette consumption and its potential as a smoking cessation method remain controversial due to limited evidence.[117] Moreover, it has been reported that the heating process itself can lead to the formation of new decomposition compounds of questionable toxicity.[117] There is concern that e-cigarettes may result in many smokers rejecting historically effective smoking quitting smoking methods.[142] Concern exists that the majority of smokers attempting to quit with the help of vaping may stop smoking but will keep on using nicotine, because their long-term effects are not clear.[171] Since e-cigarettes are intended to be used repeatedly, they can conveniently be used for an extended period of time, which may contribute to increased adverse effects.[172]

The most frequently reported less harmful effects of vaping compared to smoking were reduced shortness of breath, reduced cough, reduced spitting, and reduced sore throat.[144] More serious adverse effects frequently related with smoking cessation including depression, insomnia, and anxiety are uncommon with e-cigarette use.[62] Many health benefits are associated with switching from tobacco products to e-cigarettes including decreased weight gain after smoking cessation and improved exercise tolerance.[173] Reported in 2013, quitting smoking with the use of a vape alleviated chronic idiopathic neutrophilia in a smoker.[174] Vaping is possibly harmful by virtue of putting off quitting smoking, serving as a gateway to tobacco use in never-smokers or causing a return to smoking in former smokers.[175] Many individuals use e-cigarettes as a way to quit smoking, but there is not clear evidence that e-cigarettes help people quit smoking entirely.[164] E-cigarettes may help smokers reduce the number of cigarettes they smoke, though decreasing daily cigarette use is still not safe.[164]

They are similar in toxicity to other nicotine replacement products,[176] but e-cigarettes manufacturing standards are variable standards, and many as a result are probably more toxic than nicotine replacement products.[177] E-cigarettes produce more toxicants than other forms of nicotine replacement products and are likely to be more harmful.[178] The most frequently cited adverse effects related to nicotine vaping in studies were throat and mouth irritation, cough, nausea, and headache.[179]

Effects on vaping cessation

The short-term effects of vaping causing greater airway resistance and inflammation may not be permanent following quitting vaping.[60] A 2022 review states that a better choice for quitting smoking or quitting nicotine might be to immediately stop using e-cigarettes and smoking combustible cigarettes, which might be a better way to reduce organ injuries.[180] Cardiotoxicity can be irreversible, when necrosis or apoptosis of the myocardial cells occurs, or reversible, as in the case of short-term nicotine product consumption.[24]

Primary-care interventions

Research indicates that screening patients for e-cigarette usage in primary practice is not frequently undertaken by medical practitioners.[181] A 2015 study found a low prevalence of screening for e-cigarettes in primary-care practice relative to smoking screening (14% versus 86%) in a sample of 776 practitioners across the United States.[181] This low uptake is concerning, given the serious health risks of e-cigarettes.[181] A 2016 qualitative study in the US further confirmed that there is insufficient knowledge of e-cigarettes among physicians, including both the potential benefits and health risks.[181] A 2017 study in US college students found that most students did not receive any form of counseling about risks from medical practitioners, including dental hygienists.[181] Studies have also shown that there is a need for stronger education on e-cigarettes in medical curricula, which will allow physicians to begin addressing e-cigarette use in teenagers.[181]

As of 2022, there is little information on primary-care interventions for e-cigarette use in teenagers and young adults.[181] A 2020 case study of a 23-year-old e-cigarette user shows promising results for tapering e-cigarette use with the assistance of a pharmacist, which suggests that different healthcare practitioners may play a role helping patients with gradually tapering off e-cigarettes.[181] A 2021 randomized controlled trial of asthmatic teenagers who attended one of four clinics found that physicians discussed smoking during 38.2% of thee visits, but vaping was never brought up as a topic.[181] According to a 2022 review, this emphasizes that physicians should discuss both smoking and vaping during appointments, in particular in youth presenting with asthma.[181]

Overall risk relative to smoking

—Yogi H Hendlin and colleagues, American Journal of Public Health[135]

A 2018 Public Health England (PHE) report stated, "The previous estimate that, based on current knowledge, vaping is at least 95% less harmful than smoking remains a good way to communicate the large difference in relative risk unambiguously so that more smokers are encouraged to make the switch from smoking to vaping," but noted that this in no way means that vaping is safe.[182] They also noted it is associated with some risks as well as uncertainties.[48] A 2015 PHE report stated that e-cigarettes are estimated to be 95% less harmful than smoking,[183] but the studies used to support this estimate were viewed as having a weak methodology.[184] The estimate has been extensively disputed in medical journals.[185] Many vigorously criticized the validity of the estimate that vaping is 95% less harmful than smoking.[157] The PHE's encouragement of using vaping products has been characterized as "a reckless and irresponsible decision".[48]

Influential health organizations in England, including PHE, the Royal College of Physicians, the Royal Society for Public Health, and the National Health Service, have unequivocally stated that e-cigarettes are 95% safer than traditional cigarettes.[158] This claim originated from a single consensus meeting of 12 people convened by D.J. Nutt in 2014.[158] They reached this conclusion without citing any specific evidence.[158] The Nutt et al. paper did include this caveat: "A limitation of this study is the lack of hard evidence for the harms of most products on most of the criteria", which has generally been ignored by those quoting this report.[158] A 2015 editorial in The Lancet identified financial conflicts of interest associated with Nutt et al., noting that "there was no formal criterion for the recruitment of the experts."[158]

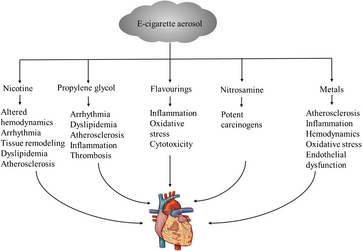

(b) Figure also shows health risks associated to chemical compounds from conventional cigarettes.[186]

The Nutt et al. meeting was funded by Euroswiss Health and Lega Italiana Anti Fumo (LIAF).[158] EuroSwiss Health is one of several companies registered at the same address in a village outside Geneva with the same chief executive, who was reported to have received funding from British American Tobacco for writing a book on nicotine as a means of harm reduction and who also endorsed BAT's public health credentials.[158] Another of Nutt's coauthors, Riccardo Polosa, was Chief Scientific Advisor to LIAF, received funding from LIAF, and reported serving as a consultant to Arbi Group Srl, an e-cigarette distributor.[158] He also received funding from Philip Morris International.[158] Polosa, founder of the Center of Excellence for the Acceleration of Harm Reduction, has repeatedly and varioulsy neglected to declare the money he was given for research came from Philip Morris International, his advisory costs from British American Tobacco, the Center of Excellence for the Acceleration of Harm Reduction’s ties to the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, and the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World’s ties to Philip Morris International.[187] In regard to the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, John Britton stated that it is "the latest in a long history of third-party organisations set up by the tobacco industry to promote its interests, and in this case act as a conduit for funds to researchers and organisations sympathetic to promoting the use of tobacco, promoting their careers, or both."[188]

Later in 2015, The BMJ published an investigative report that raised broader issues surrounding potential conflicts of interest between individuals involved in the Nutt et al. paper.[158] The BMJ provided an infographic illuminating undisclosed connections between key people involved in the paper and the tobacco and e-cigarette industries as well as links between the paper and Public Health England via one of the coauthors.[158] Even so, as of June 2017, the "95% safer" figure remains widely quoted, despite the fact that evidence of the dangers of e-cigarette use has rapidly accumulated since 2014.[158] As of 2018, the evidence indicates that the risk of e-cigarette use is substantially higher than the "95% safer" figure would indicate.[158] It was also criticized by the journal The Lancet for constructing its conclusions on 'flimsy' evidence, which included citing literature with apparent conflicts of interest.[189] It was later discovered that many of the authors who came up with the "95% safer" assertion have ties to the tobacco industry.[184] Some researchers consider that the 95% figure is flawed and confusing, by making opinions at odds with existing knowledge.[190] Despite this, most other health organizations have been more cautious in their public statements on the safety of e-cigarettes.[191]

Mortality

E-cigarette use induces an acute rise in cardiac sympathetic nerve activity.[192] This can trigger electrocardiogram abnormalities, and as a result, lead to a higher chance of sudden death in people with co-morbidities.[192] The risk of early death is anticipated to be similar to that of smokeless tobacco.[58] There is a significant risk of long-lasting lung injury from vaping that may contribute to or lead to death, in old people.[193]

Multigenerational effects

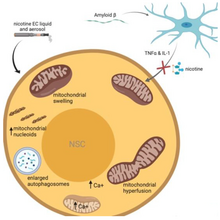

The multigenerational epigenetic effect of nicotine on lung function has been demonstrated.[195] Vaping or the use of any nicotine-based product during pregnancy or during pregnancy and during the breastfeeding, postpartum period causes the "concurrent exposure of three generations to nicotine".[196]

In 2020, mice that were exposed to nicotine during early development and their offspring showed changes in the levels of epigenetic factors that regulate gene expression in certain brain regions.[194] The observed changes were consistent with altered patterns of epigenetic modifications seen in mice and humans with neurological and behavioral disorders.[194] Epigenetic changes can persist for generations after nicotine exposure.[194] It remains unclear how nicotine exposure elicits changes in epigenetic factor levels and how these changes are passed on across generations.[194]

Maternal smoking of traditional cigarettes and maternal vaping of e-cigarettes during pregnancy exposes the fetus to nicotine; developmental nicotine exposure (DNE) can harm the baby's brain development and has been linked to disorders such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, and schizophrenia in children.[194] Of particular concern, animal model studies of maternal and grandmaternal cigarette smoking or vaping nicotine show that DNE is associated with behavioral and neurological changes that can persist across multiple generations.[194] A 2020 National Institute on Drug Abuse-funded study by Jordan M. Buck and colleagues at the University of Colorado has identified a mechanism that may be responsible for this intergenerational transmission.[194] The researchers focused on epigenetic changes—chemical modifications of the DNA and associated proteins that influence gene expression.[194] "Our findings imply that epigenetic perturbations may constitute a nexus for intergenerational transmission of DNE-induced neurodevelopmental deficits," says Buck.[194]

Regulation

Guidelines for the design, manufacture, and assessment of the safety of e-cigarette devices has not been established.[197] Following years of regulatory discussions, suggested policies and directives, e-cigarettes mainly targeting the youth continue to be underregulated, as of 2020.[198] A 2020 meta-analysis states that e-cigarettes should not be available as consumer products, though they may be considered for sale as a prescription drug.[167] A 2015 review suggested that e-cigarettes could be regulated in a similar way as inhalation therapeutic medicine, meaning, they would be regulated based on toxicology and safety clinical trials.[77] A 2014 review recommended that e-cigarettes could be adequately regulated for consumer safety with existing regulations on the design of electronic products.[199] A 2015 review recommended that regulations provide detailed quality standards for products, policies to not allow chemicals of justifiable concern, and allocate testing for plausible contaminants.[99] According to a 2020 review, regulation is needed to inform e-cigarette users of possible metal/metalloid exposure through vaping as well as to prevent metal/metalloid exposure during e-cigarette use..[200]

Regulation of the production and promotion of e-cigarettes may help lower some of the adverse effects associated with tobacco use.[201] Scientists are doing research to obtain more data regarding e-cigarettes and their usage.[202] This knowledge could result in additional regulations in the US.[202] E-cigarettes are permitted for sales in the US, though some organizations in the US have recommended they be completed banned.[112] The American Heart Association had urged a total ban on e-cigarette sales, stating that there is sufficient evidence linking e-cigarettes with adolescent's addiction to nicotine and with lure of never-smokers to smoking.[112]

In order to protect the public from both second-hand smoke and second-hand e-cigarette aerosol, the Surgeon General of the United States emphasized that smoke-free policies should be modernized to incorporate e-cigarettes, an approach that "will maintain current standards for clean indoor air, reduce the potential for renormalization of tobacco product use, and prevent involuntary exposure to nicotine and other aerosolized emissions from e-cigarettes".[203] A 2019 review states, "It is urgent to regulate e-cigarette design, e-liquid and aerosol composition, health warnings, marketing, promotion, sales, taxation, and secondhand vapor exposure at least at a level equivalent to that of regular tobacco products."[204]

Public health consequences

The public health consequence of vaping is actively being debated.[205] The health community, pharmaceutical industry, and other groups have raised concerns about the emerging phenomenon of e-cigarettes, including the unknown health risks from their long-term use.[199] The rise in e-cigarette use among the general population raises concern.[164] E-cigarettes pose potential risks to the population as a whole.[206] Concerns have been raised that higher rates of never smokers initiating e-cigarettes would result in net public health harms via increased nicotine addiction.[207] One of the serious concerns in public health is the increase in trying an e-cigarette among people who have not smoked, particularly children and adolescents, which can result in nicotine addiction and possible progression to smoking.[204] The prevalence of newer types of e-cigarettes, including Juul, with greater levels of nicotine is a public health catastrophe.[140] In December 2018, the US Surgeon General said vaping among youth is an epidemic.[140] Misinformation may downplay the risks of vape use and may be in part responsible for the recent youth vaping epidemic.[208] The rise in the rate of vaping among youth in Australia and New Zealand are a major public health concern.[61] Their indiscriminate use is a threat to public health.[57]

E-cigarettes could cause public health harm if they: increase the number of youth and young adults who are exposed to nicotine, or lead non-smokers to start smoking conventional cigarettes and other burned tobacco products such as cigars and hookah, or sustain nicotine addiction so smokers continue using the most dangerous tobacco products – those that are burned – as well as e-cigarettes, instead of quitting completely, or increase the likelihood that former smokers will again become addicted to nicotine by using e-cigarettes, and will start using burned tobacco products again.[206] A 2014 review has stated, there are "Many unanswered questions about their safety, efficacy for harm reduction and cessation, and total impact on public health."[43]

A policy statement by the American Association for Cancer Research and the American Society of Clinical Oncology has reported that "The benefits and harms must be evaluated with respect to the population as a whole, taking into account the effect on youth, adults, nonsmokers, and smokers."[73] The range of e-liquid flavors available to consumers is extensive and is used to attract both current smokers and new e-cigarette users, which is a growing public health concern.[117] The widespread availability and popularity of flavored e-cigarettes is a key concern regarding the potential public health implications of the products.[209] A critical public health concern is the increased use among pregnant women.[210] E-cigarettes are not safe for youth, young adults, pregnant women, or adults who do not currently use tobacco products.[211] Because of the risk of nicotine exposure to the fetus and adolescent causing long-term effects to the growing brain, the World Health Organization does not recommend it for children, adolescents, pregnant women, and women of childbearing age.[55] E-cigarettes are an increasing public health concern due to the rapid rise among adolescents and the uncertainty of potential health consequences.[212]

Another area of concern is the public health consequences of second-hand e-cigarette vapor on bystanders.[213] Second-hand e-cigarette vapor is a significant public health issue because of the tremendous growth in the number of e-cigarette users.[94] The use of e-cigarettes in public areas poses a serious health risk considering the various toxic constituents that have been shown to affect both the primary user and bystanders of passive vaping.[213] It is pertinent to note that smoke-free laws in the US were passed before e-cigarettes entered the market and do not specifically mention the prohibition of e-cigarette vaping in many places.[213] As such, this non-clarity may lead to non-compliance or exploitation of smoke-free rules.[213] Greater e-cigarette vapor exposure to bystanders may undermine public policies to restrict second-hand smoke and may renormalize smoking habits.[214]

Adverse effects

The short-term and long-term effects from e-cigarette use remain unclear.[61] Makers of vaping products state that these products are non-toxic, but they are correlated with a myriad of adverse effects.[125] They may cause long-term and short-term adverse effects, including airway resistance, irritation of the airways, eyes redness, and dry throat.[216] Since vaping is relatively in its infancy, it will probably take decades for long-term harm research to be available.[217] The growing evidence reinforces the idea that persistent and long-term exposure to e-cigarette aerosols possibly affects health adversely.[218] The long-term health consequences from vaping is probably somewhat greater than nicotine replacement products,[116] though repeated exposure over a long time to e-cigarette vapor poses substantial potential risk.[219] A 2016 review found "it is impossible to reach a consensus on the safety of e-cigarettes except perhaps to say that they may be safer than conventional cigarettes but are also likely to pose risks to health that are not present when neither product is used."[220] The wide range of e-cigarette products available to users and the lack of standardization of toxicological approaches towards e-cigarette evaluation complicates the assessment of adverse effects of their use.[221] Adverse effects are mostly associated with short-term use and the reported adverse effects decreased over time.[222] Long-term studies regarding the effects of constant use of e-cigarettes are unavailable.[222] Studies over one year on the effects of exposure to e-cigarettes have not been conducted, as of 2019.[223] The adverse effects of e-cigarettes on people with cancer is unknown.[73] Several serious adverse events were decribed in case studies and by news agencies.[72]

A 2015 study found serious adverse events related to e-cigarettes were hypotension, seizure, chest pain, rapid heartbeat, disorientation, and congestive heart failure but it was unclear the degree to which they were the result of e-cigarettes.[62] Less serious adverse effects include abdominal pain, dizziness, headache, blurry vision,[62] throat and mouth irritation, vomiting, nausea, and coughing.[43] Vaping induces irritation of the pharynx.[166] Short-term adverse effects reported most often were mouth and throat irritation, dry cough, and nausea.[222] The majority of adverse effects reported were nausea, vomiting, dizziness and oral irritation.[52] Some case reports found harms to health brought about by e-cigarettes in many countries, such as the US and in Europe; the most common effect were dryness of the mouth and throat.[80] Dryness of the mouth and throat is believed to stem from the ability of both propylene glycol and glycerin to absorb water.[224] Some e-cigarettes users experience adverse effects like throat irritation which could be the result of exposure to nicotine, nicotine solvents, or toxicants in the aerosol.[73] Vaping may harm neurons and trigger tremors and spasms.[225] The use of e-cigarettes has been found to be associated with nose bleeding, change in bronchial gene expression, release of cytokines and proinflammatory mediators, and increase in allergic airway inflammation which can exacerbate asthmatic symptoms, thus elevating infiltration of inflammatory cells including eosinophils into airways.[156]

Reports to the US FDA in 2013 for minor adverse effects identified with using e-cigarettes included headache, chest pain, nausea, and cough.[76] Major adverse events reported to the US FDA in 2013 included hospitalizations for pneumonia, congestive heart failure, seizure, rapid heart rate, and burns.[76] However, no direct relationship has been proven between these effects and events and e-cigarette use, and some may be due to existing health problems.[76] Many of the observed negative effects from e-cigarette use concerning the nervous system and the sensory system are probably related to nicotine overdose or withdrawal.[226] No information is available on the effects of long-term e-cigarette use on taste receptors.[77]

Youth and young adults

There is no benefit for vaping among youth[229] and, according to a 2016 review, their use in this population should be discouraged.[207] There is broad consensus on the need to protect young people from this disruptive technology.[230] Vaping is especially harmful to children and youth.[231] Multiple researchers have concluded that e-cigarettes are unsafe for youth and that allowing them to be marketed as consumer products is likely to lead to increasing youth nicotine addiction and long-term consequences seen in current research evidence.[120] Children's health has long been a concern in tobacco control.[120]

Beyond their unknown long-term effects on human health, the extended list of appealing flavors available seems to attract new "never-smokers", which is especially worrying among young users.[117] Given the unknown health effects of long-term nicotine use and inhaled propylene glycol, the safety profile of even the most reliable e-cigarette is yet unknown, and the consumption of nicotine among youth remains undesirable, there is widespread consensus concerning attempts to restrict e-cigarette sales to youth in the US.[207] A 2017 review found "Because the brain does not reach full maturity until the mid-20s, restricting sales of electronic cigarettes and all tobacco products to individuals aged at least 21 years and older could have positive health benefits for adolescents and young adults."[232] Their harmful effects on children is not well understood.[233] E-cigarettes are a source of potential developmental toxicants.[234] Children subjected to e-cigarettes had a higher likelihood of having more than one adverse effect and those were more significant than with children subjected to traditional cigarettes.[233] Significant harmful effects to children were cyanosis, nausea, and coma, among others.[233] Little is known regarding their mental health consequences on children.[235]

Frequent vaping among middle and high school students has been said to be linked to oral symptoms, such as cracked/broken teeth and tongue/cheek pain.[236] Information on the long-term health effects of vaping for adolescent and young adults are scant because of the limited amount of time they have been available.[236] There is fair evidence that coughing and wheezing is higher in adolescents who vape.[237]

According to various studies involving high school students, vapers have a twofold higher risk of chronic cough, phlegm or dyspnea, together with a greater incidence of asthma.[104] A higher prevalence of e-cigarette use is reported among adults living with a child affected by asthma, whose risk of acute exacerbation can increase by 30%.[104] Schoolwork is indirectly affected too, as a result of absenteeism secondary to the aforementioned symptoms.[104]

Reported deaths

The US Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products reported between 2008 and the beginning of 2012, 47 cases of adverse effects associated with e-cigarettes, of which eight were considered serious.[72] Two peer-reviewed reports of lipoid pneumonia were related to e-cigarette use, as well as two reports in the media in Spain and the UK.[121] In the UK, the man reportedly died from severe lipoid pneumonia[121] in 2010.[238] In August 2019, the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) reported the first death in the US linked to vaping.[239] The deceased had been recently using an e-cigarette and was hospitalized with serious respiratory problems.[239] Several people have died as a result of e-cigarette blasts with parts of the device hitting the head and neck area.[47] In March 2020, Europe announced its first confirmed death of a vaping-induced lung injury.[71] Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, one confirmed death in California has been reported to the California Department of Public Health.[240]

Poisoning

Nicotine poisoning associated with e-cigarettes may arise from inhalation, absorption, or ingestion via the skin or eyes.[73] Accidental poisoning can result from using undiluted concentrated nicotine when mistakenly used as prepared e-liquids.[242] E-cigarettes involve accidental nicotine exposure in children.[74] Accidental exposures in pediatric patients include ingesting of e-liquids and inhaling of e-cigarette vapors.[74] Choking on e-cigarette components is a potential risk.[74] In 2014, an infant died from choking on an e-cigarette component.[243] It is recommended that youth access to e-cigarettes be prohibited.[note 7][244] Concerns exist regarding poisoning, considering they may appeal to children.[243] E-liquid presents a poisoning risk, particularly for small children, who may see the colorful bottles as toys or candy.[203]

The e-liquid can be toxic if swallowed, especially among small children.[72] Four adults died in the US and Europe, after intentionally ingesting liquid.[121] Two children, one in the US in 2014 and another in Israel in 2013, died after ingesting liquid nicotine.[245] A two year old girl in the UK in 2014 was hospitalized after licking an e-cigarette liquid refill.[246] Death from accidental nicotine poisoning is very uncommon.[247]

Calls to US poison control centers related to e-cigarette exposures involved inhalations, eye exposures, skin exposures, and ingestion, in both adults and young children.[248] Minor, moderate, and serious adverse effects involved adults and young children.[249] Minor effects correlated with e-cigarette liquid poisoning were tachycardia, tremor, chest pain and hypertension.[250] More serious effects were bradycardia, hypotension, nausea, respiratory paralysis, atrial fibrillation and dyspnea.[250] The exact correlation is not fully known between these effects and e-cigarettes.[250] The initial symptoms of nicotine poisoning may include rapid heart rate, sweating, feeling sick, and throwing up, and delayed symptoms include low blood pressure, seizures, and hypoventilation.[251] Rare serious effects included coma, seizure, cessation of breathing, and heart attack.[252] Since June 2018, the US FDA observed a slight but noticeable increase in reports of seizures.[253] After examining poison control centers' reports between 2010 and early 2019, the US FDA determined that, between the poison control centers and the US FDA, there were a total of 35 reported cases of seizures mentioning use of e-cigarettes within that timeframe.[253] Due to the voluntary nature of these case reports, there may be more instances of seizure in e-cigarette users than have been reported.[253]

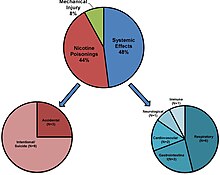

Since 2011, accidental poisoning from e-liquids that contain nicotine have grown rapidly in the US.[254] From September 1, 2010, to December 31, 2014, 58% of e-cigarette calls to US poison control centers were related to children 5 years old or less.[249] Exposures for children below the age of 6 is a concern because a small dose of nicotine e-liquid may be fatal.[252] A 2014 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report found 51.1% of the calls to US poison centers due to e-cigarettes were related to children under age 5, and about 42% of the US poison center calls were related to people age 20 and older.[255] E-cigarette calls had a greater chance to report an adverse effect and a greater chance to report a moderate or major adverse effect than traditional cigarette calls.[249] Most of the e-cigarette and traditional cigarette calls were a minor effect.[249] Severe outcomes were more than 2.5 times more frequent in children exposed to e-cigarettes and nicotine e-liquid than with traditional cigarettes.[256] E-cigarette sales were roughly equivalent to just 3.5% of traditional cigarette sales, but e-cigarettes represented 44% of the total number of e-cigarette and traditional cigarette calls to US poison control centers in December 2014.[249]

The US poison control centers reported 92.5% of children coming in contact with liquid nicotine was from swallowing during the period from January 2012 to April 2017.[252] From September 1, 2010, to December 31, 2014, the most frequent adverse effects to e-cigarettes and e-liquid reported to US poison control centers were: Ingestion exposure resulted in vomiting, nausea, drowsy, tachycardia, or agitation;[249] inhalation/nasal exposure resulted in nausea, vomiting, dizziness, agitated, or headache;[249] ocular exposure resulted in eye irritation or pain, red eye or conjunctivitis, blurred vision, headache, or corneal abrasion;[249] multiple routes of exposure resulted in eye irritation or pain, vomiting, red eye or conjunctivitis, nausea, or cough;[249] and dermal exposure that resulted in nausea, dizziness, vomiting, headache, or tachycardia.[249] The ten most frequent adverse effects to e-cigarettes and e-liquid reported to US poison control centers were vomiting (40.4%), eye irritation or pain (20.3%), nausea (16.8%), red eye or conjunctivitis (10.5%), dizziness (7.5%), tachycardia (7.1%), drowsiness (7.1%), agitation (6.3%), headache (4.8%), and cough (4.5%).[249] In nine reported calls, exposed individuals stated the device leaked.[249] In five reported calls, individuals used e-liquid for their eyes rather than use eye drops.[249] In one reported call, an infant was given the e-liquid by an adult who thought it was the infant's medication.[249] There were also reports of choking on e-cigarette components.[74]

From January 1, 2016, and April 30, 2016, the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC) reported 623 exposures related to e-cigarettes.[164] In 2016 AAPCC reported there were a total of 2,907 exposures regarding e-cigarettes and liquid nicotine.[257] The yearly nicotine exposure rate in the US involving children went up by 1398.2% from 2012 to 2015, and later dropped by 19.8% from 2015 to 2016.[252] The AAPCC reported 3,067 exposures relating to e-cigarettes and liquid nicotine in 2015, and 3,783 in 2014.[258] As of October 31, 2018, there were a total of 2,555 exposures regarding e-cigarettes and liquid nicotine in 2018.[257] The US National Poison Control database showed that in 2015 more than 1000 needed medical attention from being exposed to nicotine e-liquid.[259] Most exposures in 2015 were related to children under the age of 5.[259] The reported e-cigarette poisonings to medical centres in the UK most often happen in children under the age of five.[260] Toxic effects for children under the age of five in the UK are typically short in length and not severe.[260] From September 1, 2010, to December 31, 2014, there were at least 5,970 e-cigarette calls to US poison control centers.[249] Calls to US poison control centers related to e-cigarettes increased between September 2010 to February 2014, and of the total number of cigarettes and e-cigarettes calls, e-cigarette calls increased from 0.3% to 41.7%.[261] Calls to US poison controls centers related to e-cigarette liquid poisoning increased from 1 in September 2010 to 215 for the month of February 2014.[250] E-cigarette calls was 401 for the month of April 2014.[249] The National Poison Data System stated that exposures to e-cigarettes and liquid nicotine among young children is rising significantly.[262] The California Poison Control System reported 35 cases of e-cigarette contact from 2010 to 2012, 14 were in children and 25 were from accidental contact.[52] Calls associated with e-cigarette poisoning in Texas found that 57% was associated with children under the age of 5.[216] They were accidental, and in 96% of instances happened where they lived.[216] Of these, 85% were from swallowing, and 11% from skin contact.[216]

In 2017, the US FDA states that the e-cigarette aerosol can cause problems for the user and their pets.[263] Some studies have shown that the aerosol made by these devices may expose the user and, therefore, their pets to higher-than-normal amounts of nicotine and other toxic chemicals, like formaldehyde.[263] E-cigarettes use capsules that can contain nicotine.[263] Some of these capsules can be re-filled using a special liquid.[263] Sometimes, pets—mainly dogs—find the capsules and bite them or get into the liquid refilling solution.[263] In a March 15, 2016, letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, the Texas Poison Center Network reported 11 cases of dogs being exposed to e-cigarettes or refills.[263] Moreover, there is no antidote for nicotine poisoning.[263] If someone's pet gets into an e-cigarette, nicotine capsule, or the liquid refilling solution, it is an emergency, according to the US FDA.[263] Get him or her to the veterinarian or to a veterinary emergency clinic as quickly as possible, according to the US FDA.[263] The Animal Poison Control Center states that all the nicotine toxicity cases in 2012 included 4.6% of e-cigarettes causes and it increased to 13.6% in 2013.[264]

In 2021, poison control centers documented more than 4,500 exposures associated with e-cigarette devices or nicotine-containing e-liquids.[2]

Direct exposure to e-cigarette liquid

There is a possibility that inhalation, ingestion, or skin contact can expose people to high levels of nicotine.[201] Concerns with exposure to the e-liquids include leaks or spills and contact with contaminants in the e-liquid.[265] This may be especially risky to children, pregnant women, and nursing mothers.[201] The US FDA intends to develop product standards around concerns about children's exposure to liquid nicotine.[266] E-liquid exposure whether intentional or unintentional from ingestion, eye contact, or skin contact can cause adverse effects such as seizures, anoxic brain trauma, throwing up, and lactic acidosis.[267] The liquid does quickly absorb into the skin.[268] Local irritation can be induced by skin or mucosal nicotine exposure.[269] The nicotine in e-liquid can be hazardous to infants.[270] Even a portion of e-liquid may be lethal to a little child.[271] An excessive amount of nicotine for a child that is capable of being fatal is 0.1–0.2 mg/kg of body weight.[201] Less than a 1 tablespoon of contact or ingestion of e-liquid can cause nausea, vomiting, cardiac arrest, seizures, or coma.[272] An accidental ingestion of only 6 mg may be lethal to children.[171][57]

Children are susceptible to ingestion due to their curiosity and desire for oral exploration.[256] Children could confuse the fruity or sweet flavored e-liquid bottles for fruit juices.[216] E-liquids are packed in colorful containers[249] and children may be attracted to the flavored liquids.[147] More youth-oriented flavors include "My Birthday Cake" or "Tutti Frutti Gumballs".[245] Many nicotine cartridges and bottles of liquid are not child-resistant to stop contact or accidental ingestion of nicotine by children.[273] "Open" e-cigarette devices, with a refillable tank for e-liquids, are believed to be the biggest risk to young children.[272] If flavored e-cigarettes are left alone, pets and children could be attracted to them.[274] The US FDA states that children are curious and put all sorts of things in their mouths.[275] Even if you turn away for a few seconds, they can quickly get into things that could harm them.[275] The US FDA recommends that adults can help prevent accidental exposure to e-liquids by always putting their e-cigarettes and e-liquids up and away—and out of kids' and pets' reach and sight—every time you use them.[275] The US FDA recommends to also ask family members, house guests, and other visitors who vape to keep bags or coats that hold e-cigarettes or e-liquids up and away and out of reach and sight of children and pets.[275] They recommend for children old enough to understand, explain to them that these products can be dangerous and should not be touched.[275] The US FDA states to tell kids that adults are the only people who should handle these products.[275]

As part of ongoing efforts to protect youth from the dangers of nicotine and tobacco products, the US FDA and the Federal Trade Commission announced on May 1, 2018, they issued 13 warning letters to manufacturers, distributors, and retailers for selling e-liquids used in e-cigarettes with labeling and/or advertising that cause them to resemble kid-friendly food products, such as juice boxes, candy or cookies, some of them with cartoon-like imagery.[276] Several of the companies receiving warning letters were also cited for illegally selling the products to minors.[276] "No child should be using any tobacco product, and no tobacco products should be marketed in a way that endangers kids – especially by using imagery that misleads them into thinking the products are things they would eat or drink. Looking at these side-to-side comparisons is alarming. It is easy to see how a child could confuse these e-liquid products for something they believe they have consumed before – like a juice box. These are preventable accidents that have the potential to result in serious harm or even death. Companies selling these products have a responsibility to ensure they are not putting children in harm's way or enticing youth use, and we'll continue to take action against those who sell tobacco products to youth and market products in this egregious fashion," the US FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, said in 2018.[276] E-liquids have been sold in packaging that looks similar to Tree Top-brand juice boxes, Reddi-wip whipped cream, and Sour Patch Kids gummy candy.[277]

The US FDA announced on August 23, 2018, that all 17 manufacturers, distributors and retailers that were warned by the agency in May, have stopped selling the nicotine-containing e-liquids used in e-cigarettes with labeling or advertising resembling kid-friendly food products, such as juice boxes, candy or cookies that were identified through warning letters as being false or misleading.[278] Following the warning letters in May, the US FDA worked to ensure the companies took appropriate corrective action – such as no longer selling the products with the misleading labeling or advertising – and issued close-out letters to the firms. The agency expects some of the companies may sell the products with revised labeling that addresses the concerns expressed in the warning letters.[278] "Removing these products from the market was a critical step toward protecting our kids. We can all agree no kid should ever start using any tobacco or nicotine-containing product, and companies that sell them have a responsibility to ensure they aren't enticing youth use. When companies market these products using imagery that misleads a child into thinking they're things they've consumed before, like a juice box or candy, that can create an imminent risk of harm to a child who may confuse the product for something safe and familiar," said US FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb.[278]

Nicotine toxicity is of concern when e-cigarette solutions are swallowed intentionally by adults as a suicidal overdose.[162] Seizures or convulsions are known potential side effects of nicotine toxicity and have been reported in the scientific literature in relation to intentional or accidental swallowing of e-liquid.[253] Six people attempted suicide by injecting e-liquid.[121] One adolescent attempted suicide by swallowing the e-liquid.[74] Three deaths were reported to have resulted from swallowing or injecting e-liquid containing nicotine.[121] An excessive amount of nicotine for an adult that is capable of being fatal is 0.5–1 mg/kg of body weight.[201] An oral lethal dose for adults is about 30–60 mg.[144] However the widely used human LD50 estimate of around 0.8 mg/kg was questioned in a 2013 review, in light of several documented cases of humans surviving much higher doses; the 2013 review suggests that the lower limit resulting in fatal events is 500–1000 mg of ingested nicotine, which is equivalent to 6.5–13 mg/kg orally.[279] Reports of serious adverse effects associated with acute nicotine toxicity that resulting in hospitalization were very uncommon.[174] Death from intentional nicotine poisoning is very uncommon.[247] Clear labeling of devices and e-liquid could reduce unintentional exposures.[249] Child-proof packaging and directions for safe handling of e-liquids could minimize some of the risks.[270] Some vaping companies willingly used child-proof packaging in response to the public danger.[243] In January 2016, the Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act of 2015 was passed into law in the US,[280] which requires child-proof packaging.[281] The nicotine exposure rate in the US has since dropped by 18.9% from August 2016 to April 2017, following the Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act of 2015, a federal law mandating child-resistant packaging for e-liquid, came into effect, on July 26, 2016.[252] The states in the US that did not already have a law, experienced a notable decline in the average number of exposures during the 9 months after the Child Nicotine Poisoning Prevention Act of 2015 came into effect compared to before it became law.[252] E-liquids have been observed in 2016 to include a press-and-turn feature similar to what is used for aspirin.[243] E-liquids that were normally available in bottles that were not regarded as child-resistant, have been reported in 2016.[243]

There was inconsistent labeling of the actual nicotine content on e-liquid cartridges from some brands,[43] and some nicotine has been found in ‘no nicotine' liquids.[79] A 2015 PHE report noted overall the labelling accuracy has improved.[282] Most inaccurately-labelled examples contained less nicotine than stated.[282] Due to nicotine content inconstancy, it is recommended that e-cigarette companies develop quality standards with respect to nicotine content.[90]

Because of the lack of production standards and controls, the pureness of e-liquid are generally not dependable, and testing of some products has shown the existence of harmful substances.[270] The German Cancer Research Center in Germany released a report stating that e-cigarettes cannot be considered safe, in part due to technical flaws that have been found.[171] This includes leaking cartridges, accidental contact with nicotine when changing cartridges, and potential of unintended overdose.[171] The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) of Australia has stated that, "Some overseas studies suggest that electronic cigarettes containing nicotine may be dangerous, delivering unreliable doses of nicotine (above or below the stated quantity), or containing toxic chemicals or carcinogens, or leaking nicotine. Leaked nicotine is a poisoning hazard for the user of electronic cigarettes, as well as others around them, particularly children."[283]

Cannabinoid-enriched e-liquids require lengthy, complex processing, some being readily available online despite lack of quality control, expiry date, conditions of preservation, or any toxicological and clinical assessment.[284] The health effects specific to vaping these cannabis preparations is largely unknown.[284] There is a connection between cannabis vaping and a variety of unwelcomed health effects.[285]

Concern exists from the risk of injury associated with e-cigarette explosions for adults and children.[74] The exact causes of such incidents are not yet clear.[286] Most e-cigarettes use lithium batteries, the improper use of which may result in accidents.[52] Most fires caused by vaporing devices are a result of the lithium batteries becoming too hot and igniting.[287] Defective e-cigarette batteries have been known to cause fires and explosions.[288] The chance of an e-cigarette blast resulting in burns and projectile harms greatly rises when using low-quality batteries, if stored incorrectly or was altered by the user.[289] E-cigarettes are frequently not made by tobacco or pharmaceutical firms, but by independent manufacturers with little quality control in the making of the e-cigarette device and battery.[290] Inexpensive manufacturing with poor quality control could account for some of the explosions.[197] It has been recommended that manufacturing quality standards be imposed in order to prevent such accidents.[52] Better product design and standards could probably reduce some of the risks.[265] There can be manufacturing defects and damage to the e-cigarette device.[291]

It is recommended that users be informed of appropriate charging and storage methods.[292] In the event the lithium ion substances leak from the battery as a result of an e-cigarette blast, first aid is recommended to prevent additional chemical reaction.[292] An e-cigarette blast can induce serious burns and harms that need thorough and lengthy medical treatment particularly when a device goes off in hands, mouths, or pockets.[293] A 2017 review found "The electrolyte liquid within the lithium ion battery cells is at risk for overheating, thus building pressure that may exceed the capacity of the battery casing. This "thermal runway" [sic] can ultimately result in cell rupture or combustion."[294] Some lithium-ion batteries used in e-cigarettes do not have any protection to prevent the coil from overheating.[290] Metal objects, including coins or keys, can cause a short circuit when kept with batteries, which can result in overheating of the battery.[294] It is recommended to use insulated protective cases for batteries not in use to lessen the potential risk related to thermal runaway.[295] There are vaping devices available that are made with safety features such as firing buttons locks, vent holes, and protection against overcharging..[296] Swallowing e-cigarette batteries can be toxic.[297]