Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus

| Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Kitrinoviricota |

| Class: | Alsuviricetes |

| Order: | Martellivirales |

| Family: | Togaviridae |

| Genus: | Alphavirus |

| Species: | Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus

|

| Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

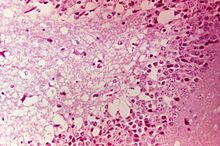

Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus is a mosquito-borne viral pathogen that causes Venezuelan equine encephalitis or encephalomyelitis (VEE). VEE can affect all equine species, such as horses, donkeys, and zebras. After infection, equines may suddenly die or show progressive central nervous system disorders. Humans also can contract this disease. Healthy adults who become infected by the virus may experience flu-like symptoms, such as high fevers and headaches. People with weakened immune systems and the young and the elderly can become severely ill or die from this disease.

The virus that causes VEE is transmitted primarily by mosquitoes that bite an infected animal and then bite and feed on another animal or human. The speed with which the disease spreads depends on the subtype of the VEE virus and the density of mosquito populations. Enzootic subtypes of VEE are diseases endemic to certain areas. Generally these serotypes do not spread to other localities. Enzootic subtypes are associated with the rodent-mosquito transmission cycle. These forms of the virus can cause human illness but generally do not affect equine health.

Epizootic subtypes, on the other hand, can spread rapidly through large populations. These forms of the virus are highly pathogenic to equines and can also affect human health. Equines, rather than rodents, are the primary animal species that carry and spread the disease. Infected equines develop an enormous quantity of virus in their circulatory system. When a blood-feeding insect feeds on such animals, it picks up this virus and transmits it to other animals or humans. Although other animals, such as cattle, swine, and dogs, can become infected, they generally do not show signs of the disease or contribute to its spread.

The virion is spherical and approximately 70 nm in diameter. It has a lipid membrane with glycoprotein surface proteins spread around the outside. Surrounding the nuclear material is a nucleocapsid that has an icosahedral symmetry of T = 4, and is approximately 40 nm in diameter.

Viral subtypes

Serology testing performed on this virus has shown the presence of six different subtypes (classified I to VI).[1] These have been given names, including Mucambo, Tonate, and Pixuna subtypes. There are seven different variants in subtype I, and three of these variants, A, B, and C are the epizootic strains.[citation needed]

The Mucambo virus (subtype III) appears to have evolved ~1807 AD (95% credible interval: 1559–1944).[2] In Venezuela the Mucambo subtype was identified in 1975 by Jose Esparza and J. Sánchez using cultured mosquito cells.[3]

Epidemiology

In the Americas, there have been 21 reported outbreaks of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus.[4] Outbreaks occurred in Central American and South American countries. This virus was isolated in 1938, and outbreaks have been reported in many different countries since then. Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, and the United States are just some of the countries that have reported outbreaks.[5] Outbreaks of VEE generally occur after periods of heavy precipitation that cause mosquito populations to thrive.[4]

Between December 1992 and January 1993, the Venezuelan state of Trujillo experienced an outbreak of this virus. Overall, 28 cases of the disease were reported along with 12 deaths. June 1993 saw a bigger outbreak in the Venezuelan state of Zulia, as 55 humans died as well as 66 equine deaths.[6]

A much larger outbreak in Venezuela and Colombia occurred in 1995. On May 23, 1995, equine encephalitis-like cases were reported in the northwest portion of the country. Eventually, the outbreak spread more towards the north as well as to the south. The outbreak caused about 11,390 febrile cases in humans as well as 16 deaths. About 500 equine cases were reported with 475 deaths.[7][1]

An outbreak of this disease occurred in Colombia on September 1995. This outbreak resulted in 14,156 human cases that were attributable to Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus with 26 human deaths.[8] A possible explanation for the serious outbreaks was the particularly heavy rain that had fallen. This could have caused increased numbers of mosquitoes that could serve as vectors for the disease. A more likely explanation is that deforestation caused a change in mosquito species. Culex taenopius mosquitos, which prefer rodents, were replaced by Aedes taeniorhynchus mosquitoes, which are more likely to bite humans and large equines.[citation needed]

Though the majority of VEE outbreaks occur in Central and South America, the virus has potential to outbreak again in the United States. It has been shown the invasive mosquito species Aedes albopictus is a viable carrier of VEEV.[8]

Vaccine

There is an inactivated vaccine containing the C-84 strain for VEEV that is used to immunize horses. Another vaccine, containing the TC-83 strain, is only used on humans in military and laboratory positions that risk contracting the virus. The human vaccine can result in side effects and does not fully immunize the patient. The TC-83 strain was generated by passing the virus 83 times through a guinea pig heart cell culture; C-84 is a derivative of TC-83.[9]

Society and culture

In April 2009, the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick reported that samples of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus were discovered missing during an inventory of a group of samples left by a departed researcher. The report stated the samples were likely among those destroyed when a freezer malfunctioned.[10]

Biological weapon

During the Cold War, both the United States biological weapons program and the Soviet biological weapons program researched and weaponized VEE.[11] In his book Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World, author Stephen Handelman details the weaponization of VEE and other biologicals including plague, anthrax, and smallpox, by Dr. Ken Alibek in the Cold War Soviet weapons programs.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b Vlak, Just M. (July 2007). "Gernot H. Bergold (1911–2003)". Journal of Invertebrate Pathology. 95 (3): 231–232. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2007.03.015.

- ^ Auguste, Albert J.; Volk, Sara M.; Arrigo, Nicole C.; Martinez, Raymond; Ramkissoon, Vernie; Adams, A. Paige; Thompson, Nadin N.; Adesiyun, Abiodun A.; Chadee, Dave D.; Foster, Jerome E.; Travassos Da Rosa, Amelia P.A.; Tesh, Robert B.; Weaver, Scott C.; Carrington, Christine V.F. (September 2009). "Isolation and phylogenetic analysis of Mucambo virus (Venezuelan equine encephalitis complex subtype IIIA) in Trinidad". Virology. 392 (1): 123–130. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2009.06.038. PMC 2804100. PMID 19631956.

- ^ Esparza, J.; Sánchez, A. (June 1975). "Multiplication of Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis (Mucambo) virus in cultured mosquito cells". Archives of Virology. 49 (2–3): 273–280. doi:10.1007/BF01317545. PMID 813617. S2CID 20202029.

- ^ a b Weaver, Scott C.; Ferro, Cristina; Barrera, Roberto; Boshell, Jorge; Navarro, Juan-Carlos (7 January 2004). "Venezuelan equine encephalitis". Annual Review of Entomology. 49 (1): 141–174. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123422. PMID 14651460.

- ^ Osorio, Jorge E.; Yuill, Thomas M. (2017). "Venzuelan Equine Encephalitis". In Beran, George W. (ed.). Handbook of zoonoses. Vol. Section B Viral Zoonoses. CRC Press. ISBN 9781351441797.[page needed]

- ^ Rico-Hesse, R; Weaver, S C; de Siger, J; Medina, G; Salas, R A (6 June 1995). "Emergence of a new epidemic/epizootic Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in South America". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 92 (12): 5278–5281. Bibcode:1995PNAS...92.5278R. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.12.5278. PMC 41677. PMID 7777497.

- ^ Acha, Pedro N.; Szyfres, Boris (2001). Zoonoses and Communicable Diseases Common to Man and Animals: Chlamydioses, rickettsioses, and viroses. Pan American Health Org. ISBN 978-92-75-11580-0.[page needed]

- ^ a b Beaman, Joseph R.; Turell, Michael J. (1 January 1991). "Transmission of Venezuelan Equine Encephalomyelitis Virus by Strains of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) Collected in North and South America". Journal of Medical Entomology. 28 (1): 161–164. doi:10.1093/jmedent/28.1.161. PMID 2033608.

- ^ "Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus".

- ^ Shaughnessy, Larry (22 April 2009). "Army: 3 vials of virus samples missing from Maryland facility". CNN.

- ^ Croddy, Eric (2002). "The Post-World War II Era and the Korean War". Chemical and Biological Warfare: A Comprehensive Survey for the Concerned Citizen. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-387-95076-1.

Notes

- APHIS. 1996. Venezuelan Equine Encephalomyelitis

- "PAHO: Equine Encephalitis in the Event of a Disaster". Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- "PAHO Epidemiological Bulletin: Outbreak of Venezuelan Equine Encephalities". Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- "PATHINFO: Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus". Archived from the original on 2006-08-28. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- "Army: 3 vials of virus samples missing from Maryland facility". CNN. 2009-04-22. Retrieved 2009-04-23.

External links

- CS1: long volume value

- Wikipedia articles needing page number citations from July 2020

- Articles with short description

- Short description matches Wikidata

- Articles with 'species' microformats

- Short description is different from Wikidata

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2022

- Arthropod-borne viral fevers and viral haemorrhagic fevers

- Alphaviruses

- Horse diseases

- Animal viral diseases

- Biological weapons

- Viral encephalitis

- Health in Venezuela

- Biological anti-agriculture weapons